Perhaps the objects that carry the most meaning in our lives, the ones that are most imbued with the connections we have with the significant people in our pasts, the ones that both store and release the memories that are fundamental to our idea of ourselves, are not so much the precious heirlooms or heritage pieces but rather the ordinary objects that we use every day, just as, perhaps, their previous owners used them every day before us. The kitchen probably holds the greatest concentration of such useful-and-meaningful objects, come to us in many different ways, each with its own story. Bee Wilson’s thoughtful and beautifully written book tells the stories attached to 35 kitchen objects of many origins, and gives insight into the texture of the lives of the people who used them, and their importance to the people who use them now.

The hands holding the book in the painting by Markus Schinwald, and the black curtains between which they protrude, are painted in such a way as to make the viewer suspect that they are looking at a painting, or a part of a painting, by some Old Master, and the viewer, upon researching further, feels a little cheated to find that the artist is still alive. Had we perhaps confused even the name Markus Schinwald with that of some minor Germanic Old Master — perhaps a painter of agonising crucifixions, memento mori and surgically accurate Sts. Sebastians — which would have given this painting, in which the person holding the book into the light is effectively bodiless, concealed behind curtains, a disconcertingly suppressed reference to physical suffering? Maybe we should not feel cheated. Maybe it is the reference to the reference, by way of our confusion, that gives the painting, for us, its meaning.

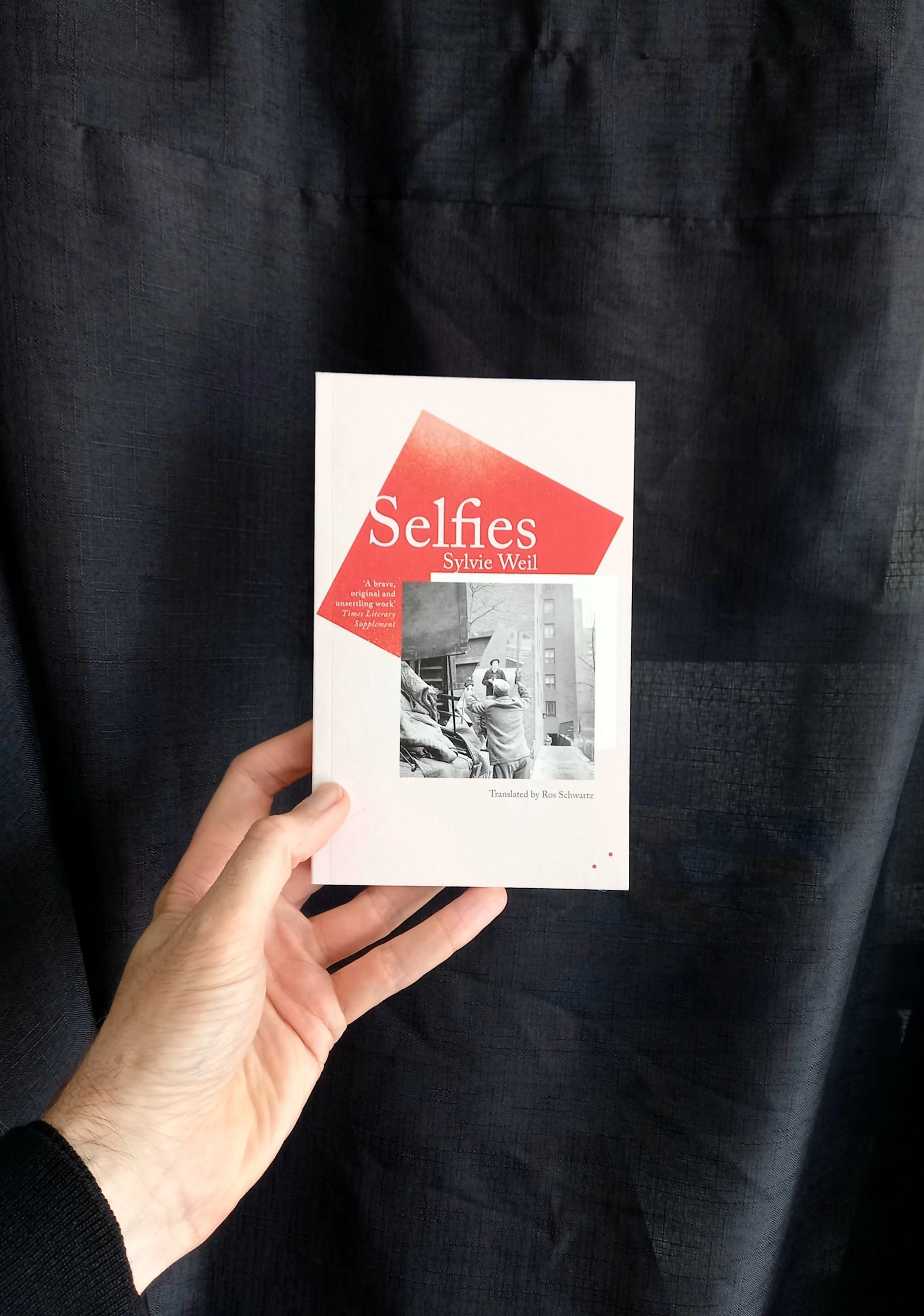

In the picture I didn't end up taking of myself I am sitting in an elderly armchair, the pile of its plush worn to the ghost of its original pattern on the arms and upper back. Beside me is a rather spindly green table upon which sits a vase of lilies, somewhat past their best, and a small empty coffee cup, a lip-mark of coffee at its rim. The sideboard behind me is stacked with books, and the fading light falls from my right onto the book I hold at an odd angle as if trying to postpone the moment in which I will have to get up and switch on a light. I am wearing something black and nondescript, seemingly a skivvy of some sort, liberally decorated with white cat hairs, and my head is thrust awkwardly forward over the oddly angled book, which I seem to be on the verge of finishing. Its title can be read despite the shadow: Selfies by Sylvie Weil.

*

The thirteen exquisite pieces of memoir that comprise Selfies each begin with a description of an actual artwork, a self-portrait by a woman ranging from the thirteenth century to today. This ekphrasis is followed by a description of a (possibly hypothetical) self-portrait by Weil which echoes or resonates with the historical work and provides a means of access to the third section of each piece, a more (but variously) lengthy examination of one of the more significant or uncomfortable aspects of Weil’s life. This tripartite structure demonstrates how viewing art can unlock new levels of understanding of our own lives, and how the communication of a stranger’s moment by means of a surface invariably stimulates the viewer’s memory to read that moment in terms of moments from the viewer’s own life, moments pressing at the surface of consciousness from the other side, so to speak. Viewing is remembering. The rigour and delicacy Weil demonstrates in viewing the artists’ works allows her to apply a similar set of criteria to her own memory-images, resulting in a remarkably nuanced set of realisations to be accessed and conveyed, potentially provoking a similar deepening of access in a reader to their his own memories. Weil’s prose, pellucidly translated from the French by Ros Schwartz, gauges subtle shifts of tone, frequently shifting our understanding of situations or persons before any knowledge about them is attained. The awful American mathematician with whom Weil had a love affair, her son’s mother-in-law, the close friend of her mother’s, the unsympathetic owners of a “Jewish” dog, are all revealed as having complex and often ambiguous relationships with the surfaces they present. Weil’s sentences, at once so straight-forward and so subtle, can move both outwards and inwards at once, operating at various depths simultaneously, as when Weil describes responses to her adult son’s mental breakdown: “I reply politely to friends who say: ‘I wouldn’t be able to cope if something like that happened to my son.’ I didn’t tell them that it could happen to anyone. And that they would cope, as people do. They’d have no choice. I don’t reply that they deserve to have it happen to them. Deep down, I agree that it is unlikely to happen to them. Not to them.” Precision often leads us to the verge of humour, as when Weil describes “the remains of a smile abruptly cut short, as if by the sudden and unexpected arrival of a dangerous animal.” The ‘Self-portrait as an author,’ springing from a description of a 1632 self-portrait of Judith Leyster seen as an advertisement for her portrait commissions (a commercial imperative), is a devastatingly perfect, almost Cuskian account of the people who visited Weil’s signing table at a literary festival. The book is full of images, or moments, details, that implant themselves in the mind of the reader and continue to resonate there in a way similar to the reader’s own memories. What is the purpose of self-depiction? “Everyone takes selfies,” Weil observes. “It’s a way of going unnoticed,” but at the same time each selfie is a form of searching, an attempt to locate oneself, somehow, in the circumstances that comprise one’s life. Memory is the only way we have to attempt to make sense of these moments.

This book begins with the question that prompted its author to stop writing for fourteen years: “Must I write?” In finally finding himself capable of addressing this question, Murnane also addresses its corollary: “Why had I written?" What follows is a subtle and often profound examination of the relationship between the ‘actual’ world and the image world from which fiction arises. Inverting the traditional Romantic model of fiction, Murnane disavows the so-called ‘imagination’ and instead stakes out the primary territory of his image world: “what I call for convenience patterns of images, in a place that I call for convenience my mind, wherever it may lie or whatever else it may be a part of”. By emphasising the porosity of a work of fiction, which is “capable of devising a territory more extensive and more detailed by far than the work itself”, Murnane shows that although the territory is landmarked by images introduced from the memory of events or fictions or artworks or other experiences, both author and reader inhabit the spaces between and surrounding these landmarks, find themselves exploring and enlarging the backgrounds of pictures and the spaces surrounding texts, and forming relationships with ‘personages’ who are both part of, and give rise to, the personages of both author and reader. Every region written about implies a further region not yet written about, “a country on the far side of fiction”, inhabited by personages who may be accessible to the personages in fiction but not yet to us. In tracing (and correlating) the memories of the personage of the narrator-Murnane and the memories of the main character in the book he abandoned when he stopped writing, Murnane gives an exacting topography of his mind (“so to call it”) and a precisely worded description of its operations, and of the yearning, distance and loneliness that both underlie and seek remedy in fiction.

All your choices are good! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

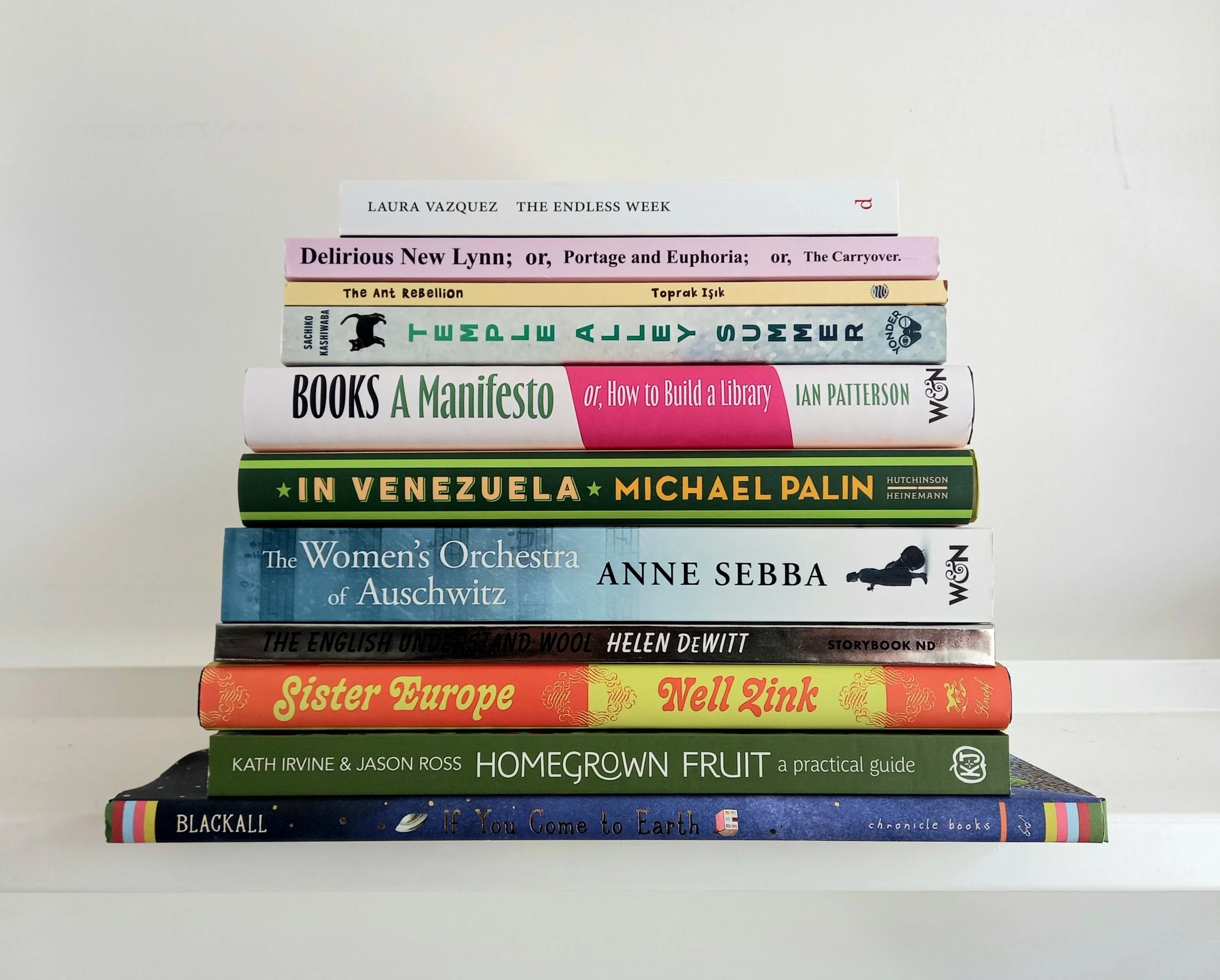

Delirious New Lynn, or, Portage and Euphoria, or, The Carryover: A guidebook by Oscar Mardell $35

Delirious New Lynn is the record of an obsession with an unnavigable backwater, a voracious drift down various culs-de-sac, an anti-psychogeography, a map of the schisms between mind and place, a poetics of trash, a rummage through the wastelands of Neoliberalism, a scavenger-hunt for meaning and nothingness, coincidence and randomness, beauty and ugliness, comedy and tragedy, comfort and horror, magnificence and absurdity, and spirituality too. Above all, it is a profusion of lists and digressions. This new book from the author of Great Works will have you in intellectual stitches as it snidely nails the Auckland suburb (and so much else about life in these times and on these shores). [Paperback]

>>Read an extract.

>>Look inside.

The Endless Week by Laura Vazquez (translated from French by Alex Niemi) $48

Like Beckett's novels or Kafka's stranger tales, The Endless Week is a work outside of time, as if novels had never existed and Laura Vazquez has suddenly invented them. And yet it could not be more contemporary, as startling and constantly new as the scrolling hyper-mediated reality it chronicles. Its characters are Salim, a young poet, and his sister Sara, who rarely leave home except virtually; their father, who is falling apart; and their grandmother, who is dying. To save their grandmother, Salim and Sara set out in search of their long-lost mother, accompanied by Salim's online friend Jonathan, though their real quest is through the landscape of language and suffering that saturates both the real world and the virtual. The Endless Week is sharp and ever-shifting, at turns hilarious, tender, satirical, and terrifying. Not much happens, yet every moment is compulsively engaging. [Paperback]

"Reading this book feels like falling into a whirlpool: it's inescapable." —Maggie Lange, W Magazine

"Vazquez has created a unique and enduring novel. Something hard and real and tangible glitters amid the vapour of text and image she describes." —Dustin Illingworth, New Left Review

"Are the kids ok? Are the elders? Are the gods? Are the dead? In this mesmeric novel, loneliness and the (online) community, language and image, the immediate and the mediated, violence and care construct a tender, precarious microzone called intimacy. A lumbar puncture of a book, a golden strain." —Joyelle McSweeney

"It's a rigorously unsettling reading experience, without plot, tension, or character development. But the details and countless vignettes deliver an immense range of emotion. Grotesquely inventive and amusing, like a corner torn from a Hieronymus Bosch painting." —Kirkus

"They say a truly great author can write about anything and make it interesting, and with The Endless Week Laura Vazquez proves that true on every page. If you're in search of an ultra-contemporary novel that shatters all the rules with inimitable humor and style to spare, look no further — she's arrived." —Blake Butler

>>Inside out experience.

Sister Europe by Nell Zink $65

As a Berlin night draws in around the pristine glass exterior of the Hotel Interconti, a ragtag group of friends, family, and potential lovers find themselves frustrated. By promise or threat, they have all gathered at a lavish celebration of an elderly author's venerable career. But dinner is delayed, the speeches are a drag and the gang — a young trans teen and her father; an ageing publisher and his flakey date; a dog, a troubled heiress and an Arab Prince — begin to feel the pinch of boredom, hunger and horniness. Together they will make their bid for freedom, and will soon embark on an exhilarating odyssey through the city's shadow and light. Sophisticated, sexy and exquisitely funny, Sister Europe is the remarkable new novel from one of the most singular, brilliant writers working today: a vivid tale of growing up, growing old and getting down. [Hardback]

"To stay out late in Zink's world, loitering, is a pleasure. Her voice is cool and fastidious, but she has a screwball quality-a comic sensibility rooted in pain. She grinds her own sophisticated colors as a writer; her ironies are finely tuned; she is uniquely alert to the absurdities of human conduct." —Dwight Garner, The New York Times Book Review

"This sly, sprightly novel provides a distraction from the news while the news is all over it. One of the pleasures of Sister Europe is that it's thoroughly up-to-date but still shaped in the timeless way of Wodehousian comedy of errors." —Sam Sacks, The Wall Street Journal

"Zink is one of the most humane writers we've got, and one of the best. As ever, Zink is funny in a way that requires careful observation and precision. The night narrated here feels like the kind of time outside of time in which classical comedies take place — a liminal space in which characters experience transformations impossible in the everyday world. Here, some characters find each other, some find their way home, and some get a bit closer to finding themselves." —Kirkus Review

”Nell Zink is a writer of extraordinary talent and range. Her work insistently raises the possibility that the world is larger and stranger than the world you think you know.” —Jonathan Franzen

”Zink writes with a joyful recklessness that makes her one of the freshest talents around.” —The Guardian

>>Not entirely sure.

>>Connecting the dots.

>>At the back.

>>Somehow connected.

Books: A manifesto, Or, How to build a library by Ian Patterson $50

This is a book about books, about the subversive power of reading and the strange, enduring magic of books as objects. Ever since childhood, books have been at the centre of Ian Patterson's life, as a poet, teacher, translator, bookseller, and collector. As he constructs the last of many libraries, he makes an impassioned case for the radical importance of reading in our lives — from Proust to Jilly Cooper, from golden-age detective novels to avant-garde poetry. Wise, irreverent and exhilaratingly wide-ranging, Books: A Manifesto reminds us that poems know things that we might not yet know ourselves, urges us to seek out the puzzles alive in the art of translation and celebrates the singular elasticity of the 'bookshop minute'. But even more than this, the book insists on reading not as a luxury but a necessary part of reality: we live within language, and when we think, it's with the tools that reading gives us. Our time of cultural and political crisis demands more than books — but without them, and without the breadth of knowledge, sense of history, awareness of alternatives and hope for the future they offer, things will not get better. At once a primer for enriching your own library and a manifesto for why that matters, this book is an invitation to a deeper, richer world of thought and feeling — and a reminder of just how much books matter. [Hardback]

”A bibliophile's autobiography, a supremely generous instruction in reading and collecting, a short history of antiquarian bookselling, a celebration of unserious pleasures and a polemic for the most serious ones — Books: A Manifesto is all of this and more. Of course Patterson hasn't read everything: he's reread it, bought and sold it a few times, might even have translated it, and has profound and genial thoughts.” —Brian Dillon

Temple Alley Summer by Sachiko Kashiwaba (translated from Japanese by Avery Fischer Udagawa), illustrated by Mihi Satake $23

Kazu knows something odd is going on when he sees a girl in a white kimono sneak out of his house in the middle of the night was he dreaming? Did he see a ghost? Things get even stranger when he shows up to school the next day to see the very same figure sitting in his classroom. No one else thinks it's weird, and, even though Kazu doesn't remember ever seeing her before, they all seem convinced that the ghost-girl Akari has been their friend for years! When Kazu's summer project to learn about Kimyo Temple draws the meddling attention of his mysterious neighbour Ms. Minakami and his secretive new classmate Akari, Kazu soon learns that not everything is as it seems in his hometown. Kazu discovers that Kimyo Temple is linked to a long forgotten legend about bringing the dead to life, which could explain Akari's sudden appearance is she a zombie or a ghost? Kazu and Akari join forces to find and protect the source of the temple's power. An unfinished story in a magazine from Akari's youth might just hold the key to keeping Akari in the world of the living, and it's up to them to find the story's ending and solve the mystery as the adults around them conspire to stop them from finding the truth. [Paperback]

”This imaginative tale, enchantingly written and charmingly illustrated by veteran Japanese creators for young people, has a timeless feel. Its captivating blend of humor and mystery is undergirded with real substance that will provoke deeper contemplation. Udagawa's translation naturally and seamlessly renders the text completely accessible to non-Japanese readers. An instant classic filled with supernatural intrigue and real-world friendship. This charming story is both a layered, profound reflection on living life with purpose and a funny, suspenseful book with all the hallmarks of classic middle-grade literature.” —Kirkus Reviews

The English Understand Wool by Helen DeWitt $36

”Maman was exigeante — there is no English word-and I had the benefit of her training. Others may not be so fortunate. If some other young girl, with two million dollars at stake, finds this of use I shall count myself justified.” Raised in Marrakech by a French mother and English father, a 17-year-old girl has learned above all to avoid mauvais ton ("bad taste" loses something in the translation). One should not ask servants to wait on one during Ramadan: they must have paid leave while one spends the holy month abroad. One must play the piano; if staying at Claridge's, one must regrettably install a Clavinova in the suite, so that the necessary hours of practice will not be inflicted on fellow guests. One should cultivate weavers of tweed in the Outer Hebrides but have the cloth made up in London; one should buy linen in Ireland but have it made up by a Thai seamstress in Paris (whose genius has been supported by purchase of suitable premises). All this and much more she has learned, governed by a parent of ferociously lofty standards. But at 17, during the annual Ramadan travels, she finds all assumptions overturned. Will she be able to fend for herself? Will the dictates of good taste suffice when she must deal, singlehanded, with the sharks of New York? A testament to the power of false friends. [Glazed hardback]

"A staggeringly intelligent examination into the nature of truth, love, respect, beauty and trust. This is that rare thing, or merle blanc, as maman might say: a perfect book. I've read it four times, which you can do between breakfast and lunch." —Nicola Shulman, The Times Literary Supplement

"This is a short, sharp sliver of a story-only 64 pages — but every single word is pitch perfect. Think of it as the literary equivalent of a shot of ice-cold vodka-Belvedere or Grey Goose only, of course." —Lucy Scholes, Prospect

"A wonderfully sideways take on the complex intersections between class, wealth and power — intersections that invariably favour those who have most of them already." -- Alex Clark, The Observer

"The English Understand Wool is Helen DeWitt's best and funniest book so far — quite a feat given the standards set by the rest of her work. Its pages are rife with wicked pleasures. It incites and rewards re-reading." —Heather Cass White, The Times Literary Supplement

If You Come to Earth by Sophie Blackall $45

Inspired by the thousands of children she has met in travels around the word for Save the Children and UNICEF, two-time Caldecott winner Sophie Blackall has crafted an ambitious yet child-accessible book of ... well ... everything. Simultaneously funny and touching, it is a call to each of us to take care of both the Earth and each other, and to celebrate the many way that people live their lives on earth. [Hardback]

>>Look inside!

The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz by Anne Sebba $40

In 1943, German SS officers in charge of Auschwitz-Birkenau ordered that an orchestra should be formed among the female prisoners. Almost fifty women and girls from eleven nations were drafted into a hurriedly assembled band that would play marching music to other inmates, forced labourers who left each morning and returned, exhausted and often broken, at the end of the day. While still living amid the most brutal and dehumanising of circumstances, they were also made to give weekly concerts for Nazi officers, and individual members were sometimes summoned to give solo performances of an officer's favourite piece of music. It was the only entirely female orchestra in any of the Nazi prison camps and, for almost all of the musicians chosen to take part, being in the orchestra was to save their lives. What role could music play in a death camp? What was the effect on those women who owed their survival to their participation in a Nazi propaganda project? And how did it feel to be forced to provide solace to the perpetrators of a genocide that claimed the lives of their family and friends? Sebba traces these tangled questions of deep moral complexity with sensitivity and care. From Alma Rose, the orchestra's main conductor, niece of Gustav Mahler and a formidable pre-war celebrity violinist, to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, its teenage cellist and last surviving member, Sebba draws on meticulous archival research and exclusive first-hand accounts to tell the full and astonishing story of the orchestra, its members and the response of other prisoners for the very first time. [Paperback]

The Ant Rebellion by Toprak Işık (translated from Turkish by Alvin Parmar), illustrated by Sedat Girgin $26

Ants are famous for their hard work, but some ants prefer exploiting others rather than doing it themselves. One day the warrior ants discover the nest of the farmer ants and set out to make the farmers their slaves — but they don’t count on the spirit of resistance from the farmers. The Ant Rebellion is a universal allegory about freedom, resistance and change, featuring memorable characters from the loving couple Honey and Glasswing to the hilarious beetle Loafer. [Paperback]

In Venezuela by Michael Palin $45

In February 2025, Michael Palin travelled to Venezuela to get a sense of what life is like in one of South America's most culturally rich, vibrant but also troubled nations. In the journal he kept during his trip he gives a vivid account of the towns and cities he visited, the landscapes he travelled through, and the people he met. Illustrated throughout with colour photographs taken on the trip, and permeated with his warmth and humour, this is a vivid and varied portrait of a complex country. [Hardback]

Homegrown Fruit: A practical guide by Kath Irvine and Jason Ross $58

Kath and Jason take you step by step to create a naturally, healthy orchard that thrives with minimal effort. You’ll learn how to choose the right varieties, plan a productive layout, build a living soil, assess tree health, and confidently prune, train, and care for your trees year-round. Real-world examples, sample plans and down-to-earth advice provide simple, practical solutions for gardens of every shape, size and climate. This inspiring, accessible book is perfect for beginners setting up a new orchard, busy people who want homegrown fruit without the fuss, and seasoned growers seeking deeper knowledge. Kath and Jason have over 25 years experience designing and managing home orchards in a diversity of environments across Aotearoa. The book's focus is on creating a healthy setup and choosing well-suited varieties. From this solid foundation fruit trees flourish, care is easy, there are a lot fewer pests and diseases and, most importantly, growing is fun! [Paperback]

A Selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

Against Identity: The wisdom of escaping the self

Death Goddess Guide to Self Love

Public, Private, Secret: On photography and the configuration of the self

Read our 464th newsletter

16 January 2026

I’m usually suspicious of self-help books, inspiration-filled pages, and daily quotes, but when Katy Hessel’s book How to Live an Artful Life arrived, I was taken with it immediately. This may have been due my prior knowledge of her podcast, ‘The Great Women Artists’, or her art history book, The Story of Art Without Men, or because dipping in, I was intrigued by the breadth of the ideas, the quotes on creativity from both artists and writers, and the amount of information packed into each daily entry, and yes, inspiration. If you’re like me, and your art practice, although being an integral part of your psyche, is in practical terms an outlier crowded out by juggling two jobs, helping to keep the wheels turning at home, looking out for and spending time with your family, and the myriad of tasks that demand attention, then this is just the thing to enable a short window of focus. And this works for artists, writers, anyone that wishes to tune in to art (‘the artful life’) or learn to be more observant; to take the time. I’ll be using this book over the year ahead —366 entries, (but you can dip in and out wherever and whenever you like), so I’ve just read today’s entry. January 16: ‘Keep Looking’. It has a quote from writer Ruth Ozeki about spending time studying something intently — seeing more as you spend more time with an image or an object. This entry has a exercise to do. Some of the entries do — not all — but they are not compulsory, and by no means necessary, as the reading and your thinking will take you places. I’ve started a journal (I’ve always kept a visual diary (since being an art student), and occasionally blogged or had a journal on the go, but these have been erratic rather than systematic efforts) to go alongside the daily entries, jotting down my reactions to the passages and noteing ideas to come back to. (I’ve got 15 full pages already, so plenty of thoughts to record and ideas sparking!). The quotes from artists and writers are drawn from Hessel’s interviews or research, and it’s great to meet some new artists, as well as ones you know. So far, I’ve encountered Ali Smith, Ana Mendieta, Zoe Leonard, Louise Bourgeois, Tacita Dean, Deborah Levy, Kiki Smith, Anni Albers, plus 8 more. One a day. Their thoughts on creativity, Hessel’s commentary and things to think about or do, as well as information about the day’s artist or writer all packed into one succinct page or even half page. For the time-poor this is wonderful, as even on a busy day you can ensure at least keeping abreast of your reading, building a daily habit of engaging with and building your artful life. What I have found the most rewarding so far is remembering an artwork I hadn’t thought about in a long time, and the experience of interfacing with that work; looking at an object which I was very familiar with and finding something new in it; discovering some new artists and being reminded about ones that had slipped out of my consciousness; being more observant and remembering to push pause on the ongoing static of everyday menial tasks and open a window for a fresh portion of art. How to Live an Artful Life is both reassuring and challenging. Reassuring in the sense that your artful life hasn’t disappeared, it’s just a little overwhelmed by other demands and distractions; and challenging because you do find yourself stopping, questioning and focusing your mind on different ways to think about your relationship with art. Highly recommended.

My life is a sort of an orbit, he thought. My life is a repetitive circular thing, or something very closely approximating a circle, not that an orbit needs to be circular, necessarily, but I think mine is. How many times will I pass this same point in the geography of my life, so to call it, how many times will I pass by, caught in the momentum of my orbit, unable to touch what I observe of my life below, changing slowly, or fast, as it does by the influence of various forces that I also cannot touch. But what am I if I am remote from what I have just called my life, he thought, what am I, the orbiting observer, if I am not my life, if I am orbiting above my life as the astronauts or cosmonauts in the space station in Samantha Harvey’s novel Orbital orbit above the planet Earth, orbiting and observing, enthralled by the attractive wonderful damaged planet below, remote from it but falling always towards it though never getting closer, in an equilibrium of gravity and momentum. An orbit, after all, he thought, is always firstly an act of attention. “Is it necessarily the case that the further you get from something the more perspective you have on it?” Harvey asks in the novel, as the astronauts stand in awe at the systems and patterns below them. “If you could get far enough away from Earth you’d be able finally to understand it.” Are understanding and participation mutually exclusive, he wondered, then, in my life, on this planet, necessarily, or is participation in itself a form of understanding, albeit enabled by an inescapable narrowing of perspective? As I circle in my orbit, far above my life, falling towards the object of my attention but carried away anyway by momentum, there in the equilibrium of my distance, I see there are no borders, no edges, no entities other than a oneness, if that could even be thought of as an entity, no entities other than those that exist in our minds, arbitrary borders, arbitrary edges, arbitrary entities, not seen from above but only by the participants in the struggle that they enable, the struggle that they condemn us to maintain. The moonshot is the opposite of an orbit. We divide ourselves with edges to get things done, to act one thing upon another, to intend and do, to participate or at least be aware of what we think of as our participation to the limited extent that we are somehow aware. This is how we get things done. This also is how harm is done. Up here in my orbit I observe how tiny all that is, I understand to the extent that I am remote, I am in a plotless place, I am in a place where everything is in an indefinite tense, where everything is a submission to a larger system, somewhere that I am hardly me. “As long as you stay in orbit you will be OK,” says the astronaut. “You will not feel crestfallen, not once.” I do not want to return, he thought. I do not want to leave my space of suspension, though “our hearts, so inflated with ecstasy at the spectacle of space, are at the same time withered by it.”

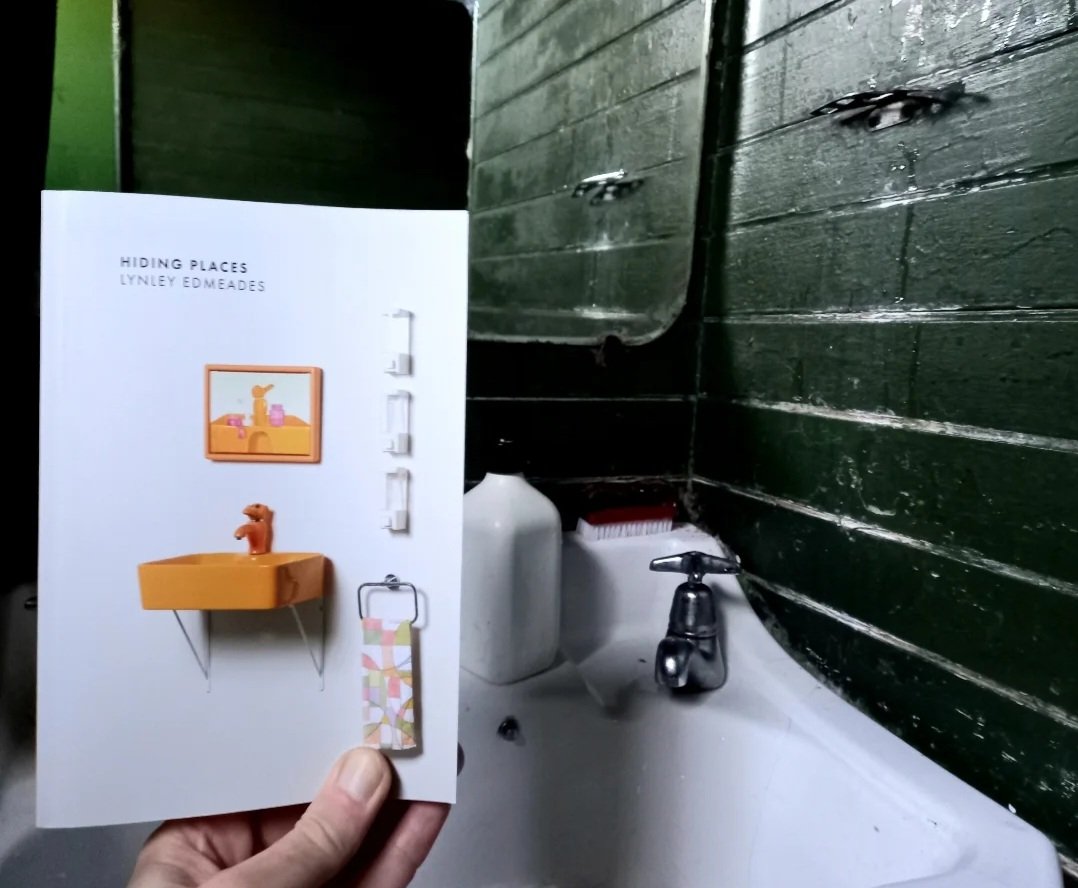

Lynley Edmeades’s Hiding Places is a book about the writing of a book (this book) in a life impacted by the arrival of a new life (a child) while caught also in a culture where both the writing of books and the raising of children are freighted with sets of judgements and expectations that make it hard to know, when you are doing either of these things best, if you are doing either of these things right (if there even is a right way of doing either of them). The fragmentary form of the book and the cumulative immediacy of the fragments, often slippery, often either pained or playful and frequently both, produce a work that is more confessionary than evasive while treasuring the possibilities of evasion, investigating shared experience while highlighting the irremediable particularity of the actual experiences it treats.

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

Read our first newsletter of the year!

Start your new year with a new book.

9 January 2026

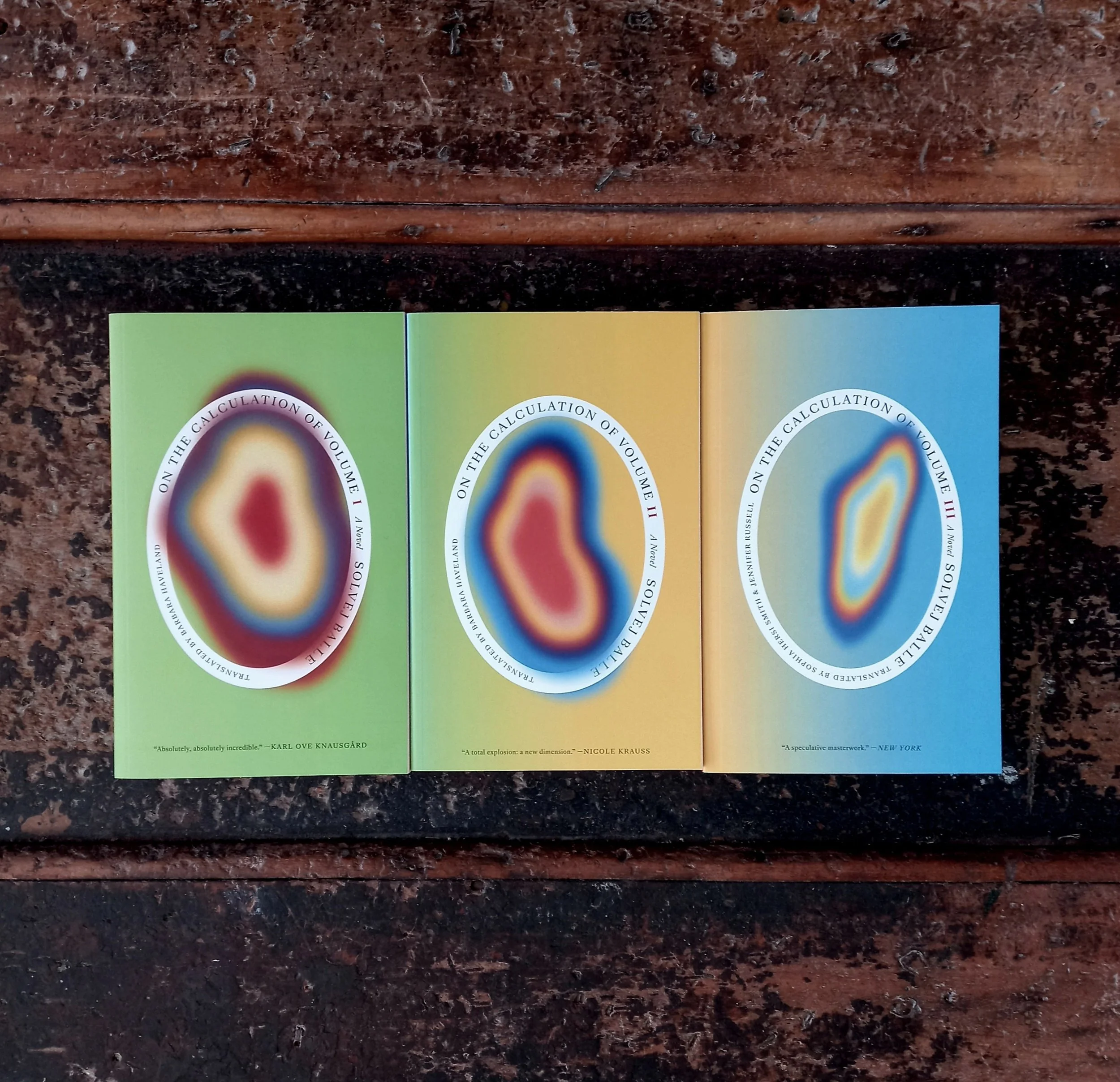

How can I write my review, or live my life, or do anything without repeating myself, I wonder. Here I go again! My life seems to consist of smaller and larger circles of repetition, my days are filled mostly of content indistinguishable from that which filled and will fill other days, barring some disaster or some miracle that is, though I have only my experience of this moment, shaded with what I call memory, inflected with what I think of as anticipation, to give me any idea of this repetition. I do experience repetition, I experience time, as if it actually exists, but how can I bear this? Any generalisation about the state of the world is a subjective state, but I suppose this endless repetition gets things done, I am a cog in the world-machine or else an untoothed wheel spinning needlessly and without traction, it is hard to tell, but I get things done. Repetition is the mode of action, but it causes me more suffering than it should. I think that perhaps I do not like getting things done. I think that I could so easily slip out of this shuddering machine, any thing could provide a way out, observing anything without the illusion of context would release me from its meaning and allow me to see it clearly, without language, without intention, without usefulness, but for what? Would this be the ultimate dislocation from my world or the ultimate dissolution in it? We repeat ourselves to keep the middle way, to preserve the idea that we have of ourselves, or the idea that others have of us. Tara Selter, in Solvej Balle’s seven-part novel On the Calculation of Volume, finds herself trapped in an endlessly repeating 18th of November, or she repeats her presence in what everyone else experiences as a single day. In this second volume, Tara decides to travel through Europe, guided by a meteorological chart, pursuing the experience of a passing year by moving to places where the conditions on the 18th of November resemble those she would associate with a changed season. She travels north to ‘winter’ and south to ‘summer’ and records the fiction of a passing year in a green notebook in a sustained attempt to live against the facts. When the notebook is stolen and does not reappear, Tara concludes, “I have had no seasons. Seasons are not scenes and locations. You cannot construct a year out of fragments of November.” She considers a Roman sestertius that she has with her and “At that moment I felt a void come into being. I felt a loss, a slide, a shift. It was as if a space was opening up, very slowly, not a big space, or at least it didn’t feel big, but I couldn’t close it again.” There is a ‘looseness’ to the world, she realises, and she is simultaneously immersed and separate from it. “I am walking around the streets, superfluous and out of circulation. It is not a disaster. It is not nothing, but it is not much either. Even the sound of my own feet is superfluous. I am walking through a space that ought to be empty. The place I occupy ought to be vacant, but for some inexplicable reason Tara Selter has taken it. I am in the way, I am a foreign body, an error. I am a strange creature who ought not to be among people with a direction.” It is solipsistic to consider myself an intruder on my own absence, as Tara does, but I suppose we are all intruders on our own absence (or absences (it is hard to know whether not existing is entirely a personal thing or something I would share with everything else that did not exist)). Everyone in this 18th of November experiences the day each time the same (there is no reiteration for them, after all), except when Tara intrudes upon their world and they are affected or respond to her. The anomalies she brings to them change their day but have no effect, for there is no day after, or if there is, Tara cannot reach it. What would be the cumulative effect of all these anomalies, the effects of Tara, if these became compound and consequential? She is right to consider herself a monster, after all. What Tara consumes is not renewed, so although it may seem that she is free from the consequences of her actions, the world, however out of joint, offers her no such liberation. Her dilemmas are those in which we all find ourselves all the time, though our lives are constructed in denial of them. We can follow no thought through to its end. We live against the facts in order to stay within the limits of the space where we can get things done. “My time is not a circle and it is not a line, it is not a wheel and it is not a river. It is a space, a room, a vessel, a container,” writes Tara. Each volume of this remarkable book provides a space for our thoughts, and equipment to stimulate its exercise.

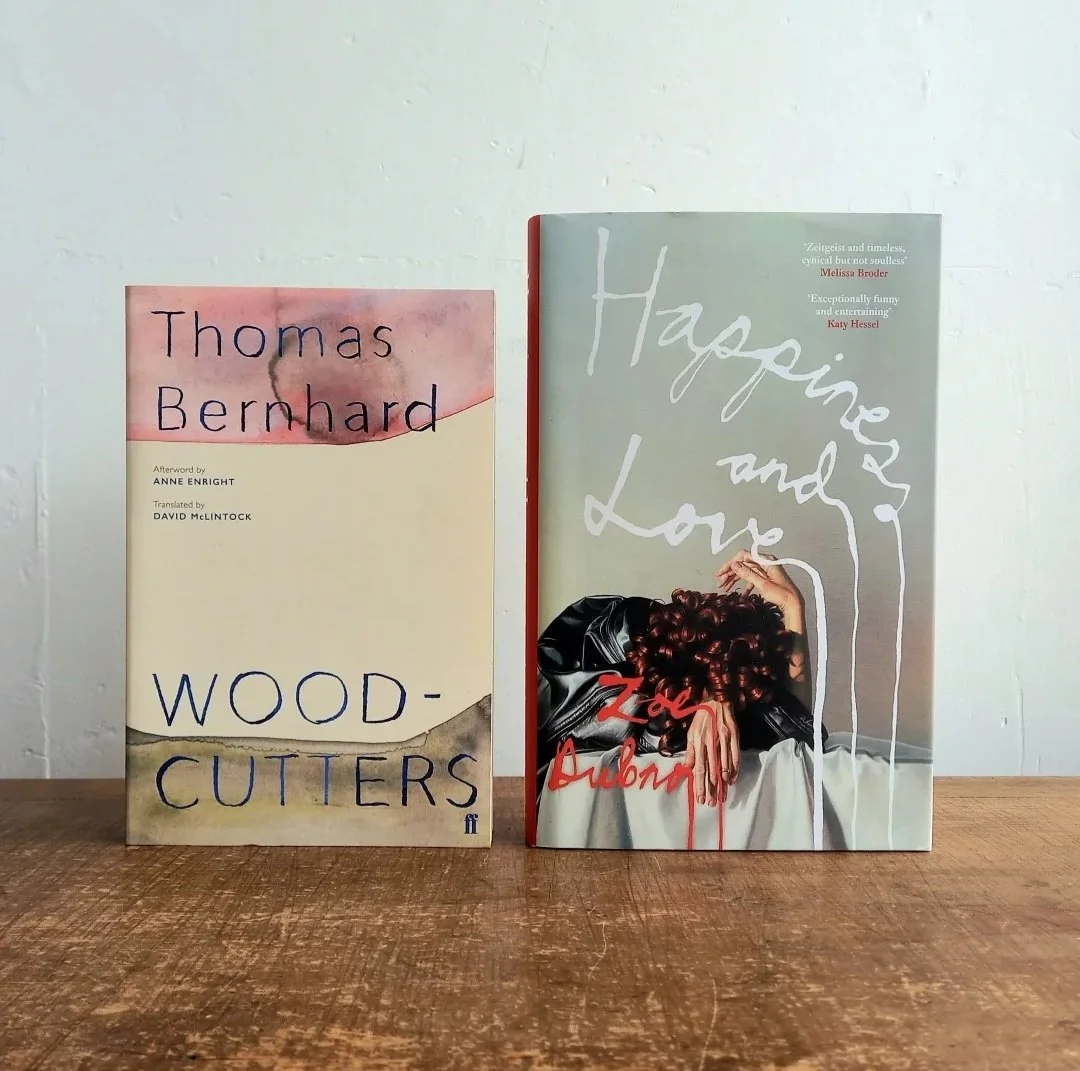

Ever found yourself at a dinner party you would rather avoid? Zoe Dubno tackles art and the creative scene, New York-style, in this sharp, slightly nasty, often wickedly funny novel. Our narrator, after escaping the claustrophobia of an art-scene couple who love to collect young artists and writers, finds herself smack back in the centre of their world again after the overdose death of Rebecca, a highly strung actress and friend. Inside the head of our narrator, we view the scene from her position seated on the white sofa in the high-end designer city loft. Here, across the room from her is the couple: Eugene pouring himself another wine and pawing a young naive hopeful artist, and Nicole, now aging, but still projecting all that money, position, and confidence can bring, regal in her control of the room and the people in it. Here too, is The Writer, Alexander, for whom our narrator has a particularly nasty case of bile. The narrator, a writer of medium success and not a lot of confidence (hardly surprising considering the company she has kept) keeps us engaged with her wry asides, observant eye (especially in retrospect — she has escaped, although now is feeling a little trapped and somewhat contrite), and laugh-out-loud snarkiness. Yet you also, like her, are a little repulsed by the company. This tension is cleverly pulled at by Dubno — letting us see, making us laugh and curl our lip simultaneously. We observe, we have our narrator’s internal dialogue of disgust and also self-loathing to digest, as well as her shocking unguestlike behaviour — several times she can hardly contain herself, breaking into barking and inappropriate laughter. As you read on, her behaviour towards this circle of writers, artists, wannabes, and the maniapulative couple at its centre is fully warranted. Here they wait for the guest of honour, a famous actress, here they say shallow things about the recently deceased Rebecca, they pontificate on their art — hint at their successes and talk up their brilliance, they fish for compliments and make snide putdowns to put others in their place, while working the room to their best advantage. Art is mentioned as if it is a by-product, merely a name-dropping convenience of what they truely want: attention. And when the dinner is finally served, the actress in her place at the head of the table, with Eugene slobbering over her as he is increasingly wine-fuelled and drug-sniffed, and Nicole sagely nodding and smiling to everything she says until… a conversation that cuts to the heart of the pretension plays out. The actress launches into a heated debate with the arrogant and soon-to-be-cut-down Alexander. Revenge for the narrator is sweet, the actress acting as a vehicle for our narrator’s distaste of the company. Zubno openly takes Thomas Bernhard’s The Woodcutters and brings it to America in the current century, using the same form — one paragraph (not that I noticed until the end) and one evening — and despite the shallow characters creates something clever, ruthless, and reflective. (I’ll be reading the original to compare.)

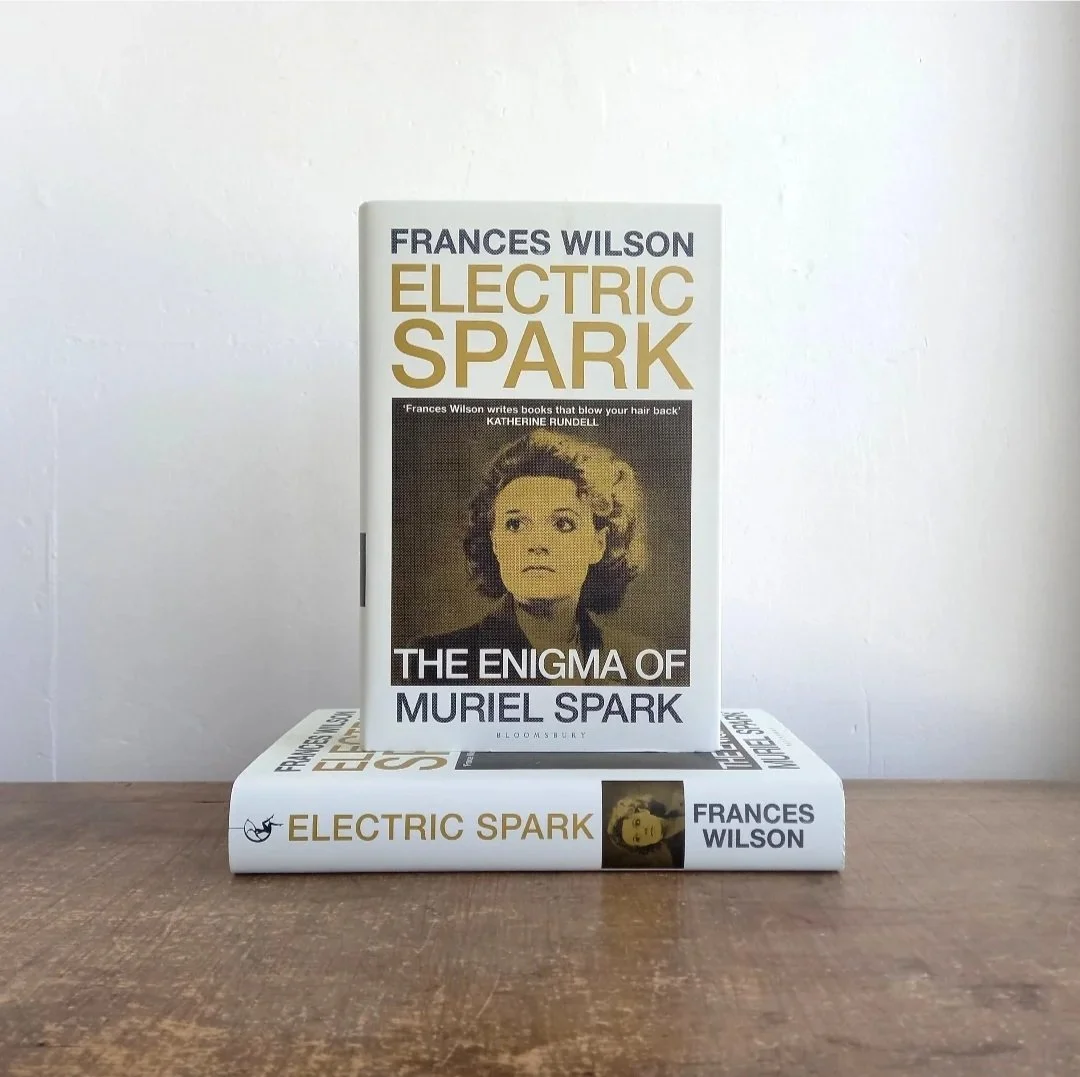

“A revolutionary book. When Spark published her first novel, The Comforters, in 1957, it was recognised as unique — something that quite simply had never been done before. Wilson's achievement in Electric Spark is equally remarkable: an entirely original method of life writing which leaves conventional biographical techniques gasping in the dust. Electric Spark heaves with ghosts and furies, burglaries and blackmail. It is disquieting and absolutely mesmerising. I was possessed by this book in the same way that I suspect its author was possessed by Spark. It still hasn't put me down.” —Lisa Hilton, Spectator

”Wilson is not any old biographer. Her books are intense, eclectic and wildly diversionary, her intelligence rising from their pages like steam — and in Spark, the cleverest and the weirdest of them all, she may have found her ultimate subject.” —Rachel Cooke, Observer

Withstand summer with a new book! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

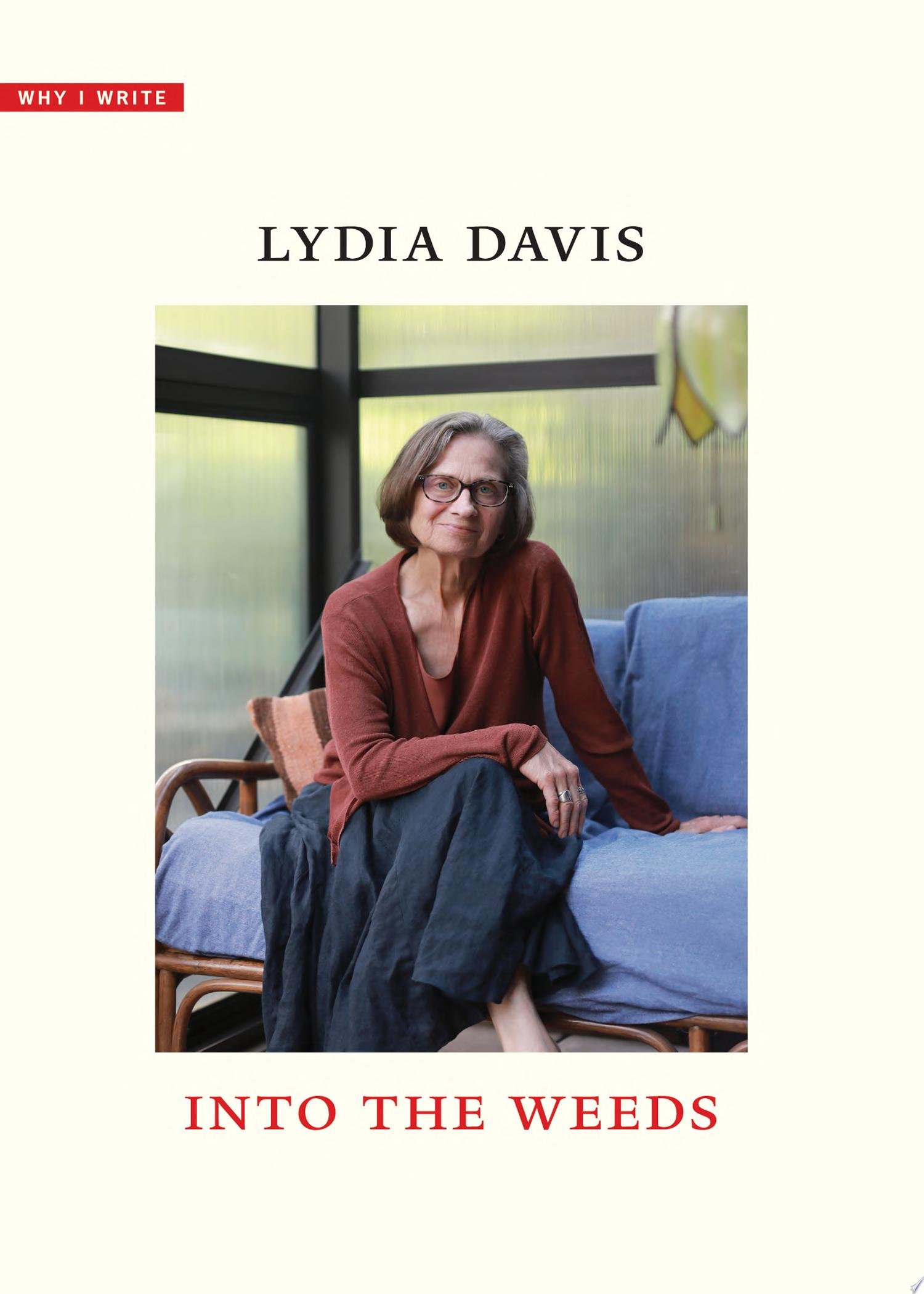

Into the Weeds by Lydia Davis $31

When asked why she writes, Lydia Davis confesses that the question makes her uncomfortable. Maybe she would rather not know. Instead, Davis considers how she writes her stories, how other writers write, and what insights the how might provide into the why. In this free-ranging exploration, Davis discovers that one reason she writes is for pleasure: the pleasure of encountering something that demands to be treated in language, of handling and manipulating the language into the form it ought to take, and, finally, of seeing a story exist where it didn't exist before. As she observes the processes of some of the authors who interest her the most, she finds that there seem to be as many reasons to write as there are writers: to relive an experience, to share an experience, to articulate something one has not quite comprehended. Reflecting on an eclectic mix of thinkers, including James Baldwin, Kate Briggs, Walter Raleigh, Christina Sharpe, Knut Hamsun, Grace Paley, Josep Pla, John Ashbery, and John Clare, Davis undertakes a clear-eyed, patient inquiry into the manifold reasons we choose to put pen to paper and begin something new. [Hardback]

"Reporting from the slipstream of her reading life, Davis offers less a new way to think than perhaps an old one, pushing back against mechanisation and the collapse of context by reframing reading in the most particular and human terms." —David L. Ulin, The Atlantic

>>On the art of observation.

>>Also by Lydia Davis.

The Earth Is Falling by Carmen Pellegrino (translated from Italian by Shaun Whiteside) $38

A haunting novel based around the existence of an abandoned village outside Naples. The deserted houses that still stand there are peopled with ghosts who live in a perpetual present from which time has effectively been abolished. The village appears to be semi-alive; the landslide which ominously awaits and which will eventually lead to the abandonment of the place has yet to arrive — yet its rumbles are heard. Pellegrino peoples Alento with eccentrics, luminaries, an eternally optimistic town crier. In the closing pages, the narrator Estella summons the remaining ghosts for a final dinner. The overall effect is unsettling, haunting and uncanny, the trapped souls doomed to repeat their circumscribed daily life for ever, cut off from the world but dimly aware of its continued presence outside. The pervading mood of nostalgia and melancholy works in stark contrast with the inevitability of the impending catastrophe of the landslide that threatens to obliterate their world forever. [Paperback]

”What people: so vibrant and vital, if ghosts can be described as such. What a place: precarious yet utterly certain in Carmen Pellegrino’s vivid, poetic rendering. And what a book: melancholy, elegant, original and in its own particular way, totally seductive.” —Wendy Erskine

The Hunger of Women by Marosia Castaldi (translated from Italian by Jamie Richards) $38

Rosa, midway through life, is alone. Her husband passed away long ago, and her cosmopolitan daughter is already out the door, keen to marry and move to the city. At loose ends, Rosa decides to transplant herself to the flat, foggy Lombardy provinces from her native Naples and there finds a way to renew herself--by opening a restaurant, and in the process coming to a new appreciation of the myriad relationships possible between women, from friendship to caregiving to collaboration to emotional and physical love. Made up of Rosa's observations, reflections, and recipes, the novel tracks her mental journey back to reconnect with her own embattled mother's age-old wisdom, forward to her daughter's inconceivable future, and laterally to the world of Rosa's new community of lovers and customers. A tribute not only to the tradition of women's writing on hearth and home but to the legacy of such boundary-breaking feminist writers as Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, and Helene Cixous. And there’s wonderful food on every page! [Paperback with French flaps]

”A hypnotic theatre of cruelty and tenderness in which the protagonist and narrator Rosa and her friends make vacuum cleaners buzz, exhibit the most lavish forms of desire, desire each other, and desperately, and above all make food, the food which is really the nourishment of the book itself, an obsession formalized here in something like a hundred recipes spread over just under two hundred pages.” —Francesco Durante, Corriere del Mezzogiorno

”The Neapolitan-Milanese Castaldi does not use punctuation, lets thought flow unchained, because life flows like water, and the search for one's identity, always painful, always exhausting, manifests even in our food, the passions in our mouths and hearts.” —Rolling Stone

>>Narrative is only partly recognisable as thoughts.

>>Eating time.

>>Syntax and effect.

Granta 172: Badlands $37

This issue traverses inhospitable landscapes, from troubled childhoods to drone-infested Ukraine. Featuring reportage from William T. Vollman and memoir from Annie Ernaux. Fiction by Brittany Newell, Leopold O’Shea, Natasha Stagg, Stephanie Wambugu and Diane Williams. Poetry by Nasim Luczaj, Paul Muldoon, Sharon Olds and Frederick Seidel. Plus, photography by Sana Badri, Joel Meyerowitz (introduced by George Prochnik) and Cian Oba-Smith (introduced by Julián Herbert). [Paperback]

From Scenes Like These by Gordon M. Williams $28

It's the west of Scotland in the 1950s. New houses are going up. Factories are opening. But Dunky Logan, a 15-year-old brought up in a tenement flat in working-class Kilcaddie, is ditching school to be a labourer on a local farm. Dead set on becoming a hard case, he wants to work shoulder to shoulder with so-called real men. Irish Catholic Mary O'Donnell arrives at the farmhouse as the new maid. She is pregnant — no boyfriend in sight. But she's smart, and she has a plan to get herself up in the world. As Dunky is swallowed up by a vicious cycle of violence, betrayal, and booze, Mary becomes entangled in a savage family feud. Short-listed for the 1969 (first!) Booker Prize. [Paperback]

”An elegy to ordinary lives. A forgotten classic entirely deserving of a place in the canon of great social realism novels of the twentieth century. A raw, unsparing tale of coming of age, of masculinity in crisis, of farm workers holding on as post-war Britain encroaches upon them. A masterpiece of time and place that looks you square in the eye and demands to be read.” —Douglas Stuart

”A devastating study of 1950s Scottish adolescence by one of the most consummate stylists of the whole post-war era. From Scenes Like These is a genuine lost classic just waiting to be rediscovered by a new generation of readers.” —DJ Taylor

Fair Play by Louise Hegarty $38

Abigail and her brother Benjamin have always been close. To celebrate his birthday, Abigail hires a grand old house and gathers their friends together for a murder mystery party. As the night goes on, they drink too much and play games. Relationships are forged, consolidated or frayed. Someone kisses someone they shouldn't, someone else's heart is broken. In the morning, everyone wakes up — except Benjamin. Suddenly everything is not quite what it seems. An eminent detective arrives determined to find Benjamin's killer. The house now has a butler, a gardener and a housekeeper. This is a locked-room mystery, and everyone is a suspect. As Abigail attempts to fathom her brother's unexpected death in a world that has been turned upside down, she begins to wonder whether perhaps the true mystery might have been his life. [Paperback]

”Louise Hegarty's genre-splicing debut is a treat — clever, confident, and always surprising, a mystery story that ingeniously escapes the locked room of the genre to take on the biggest questions of life and death.” —Paul Murray

”Dazzling, formally subversive, brimming with compassion, Fair Play explodes the conventions of a mystery in order to confront us with the genuinely mysterious. An emotional ambush of a novel, this book will delight readers — then it will haunt them.” —Colin Walsh

Vulture by Phoebe Greenwood $38

Catch-22 on speed and set in the Middle East, Vulture is a fast-paced satire of the war news industry and its moral blind spots, and a tragi-comic coming-of-age novel. An ambitious young journalist, Sara is sent to cover a war from the Beach Hotel in Gaza. The four-star hotel is a global media hub, promising safety and generator-powered internet, with hotel staff catering tirelessly to the needs of the world's media, even as their own homes and families are under threat. Sara is determined to launch her career as a star correspondent. So, when her fixer Nasser refuses to set up the dangerous story she thinks will win her a front page, she turns instead to Fadi, the youngest member of a powerful militant family. Driven by the demons of her entitled yet damaging childhood, Sara will stop at nothing to prove herself in this war, even if it means bringing disaster upon those around her. Greenwood's debut novel brings readers deep into the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and with audacity and humour depicts the media's complicity in this ongoing tragedy. [Paperback]

"Brave, funny and beautifully written." * Martin McDonagh, writer and director *

"In a debut redolent of Graham Greene, Phoebe Greenwood brings to life — in all their cynicism and all their humanity — the bullying, bragging, brilliant characters we rely on to bring us the news." —Benjamin Moser

>>Why did it take the world so long to be outraged?

Slow Down or Die: The economics of degrowth by Timothée Parrique $40

One of the most ingrained beliefs of our age is that perpetual economic growth is the solution to most, if not all, of society's problems. Parrique challenges this myth, demonstrating how producing more won't solve climate change, poverty, or inequality. In fact, our obsession with growth is accelerating social and ecological collapse. Parrique proposes a different vision — a ‘post-growth’ economy, where we look beyond the vagaries of GDP and measure our economies through how well we provide for each other. Instead of infinitely accumulating wealth, our goal must be a just, equitable, and sustainable society. [Paperback]

”A clear vision for a profoundly different economy.” —Irish Times

>>How to blow up an economy.

>>Slow is the new cool.

A Counter of Moons: Living with the unimaginable by Iona Winter $30

In 2020, Iona Winter’s son Reuben died by suicide. Looking for solace and understanding from others’ stories, she found there were few available. A Counter of Moons candidly shares Iona’s experiences, and her reflections challenge widespread ideas about how to deal with grief. At times raw and confronting, at others introspective and tender, this book ultimately speaks about the coexistence of love and pain. It aims to start conversations about suicide bereavement in Aotearoa, to give words to an often wordless experience. [Paperback]

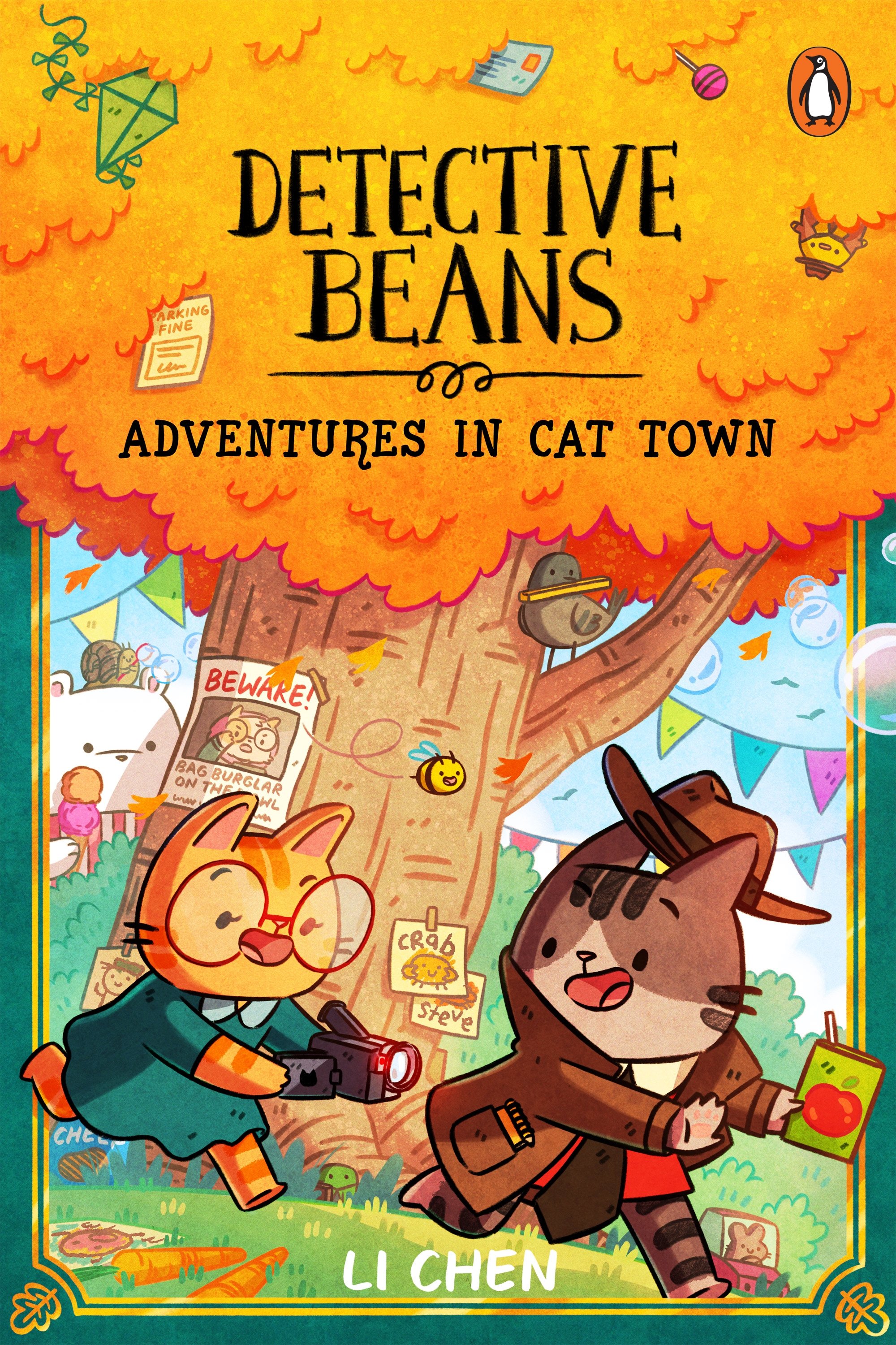

Detective Beans: Adventures in Cat Town by Li Chen $22

Detective Beans is back to solve all the mysteries that you need solved, and even the ones you don't need solved. He's that good. In between playing Scrabble, having sleepovers and trips to the beach, there's always time for crime solving. Whether it's who ate Mum's donuts, who has lost their handbag in the park, which pigeon stole King Chip, or even a burgled diamond ring, Beans is ready for anything. He's so ready that he's even starting a detective school — if he can find any students… A very enjoyable Aotearoa graphic novel for children. [Paperback]

>>Look inside!

>>The Case of the Missing Hat.

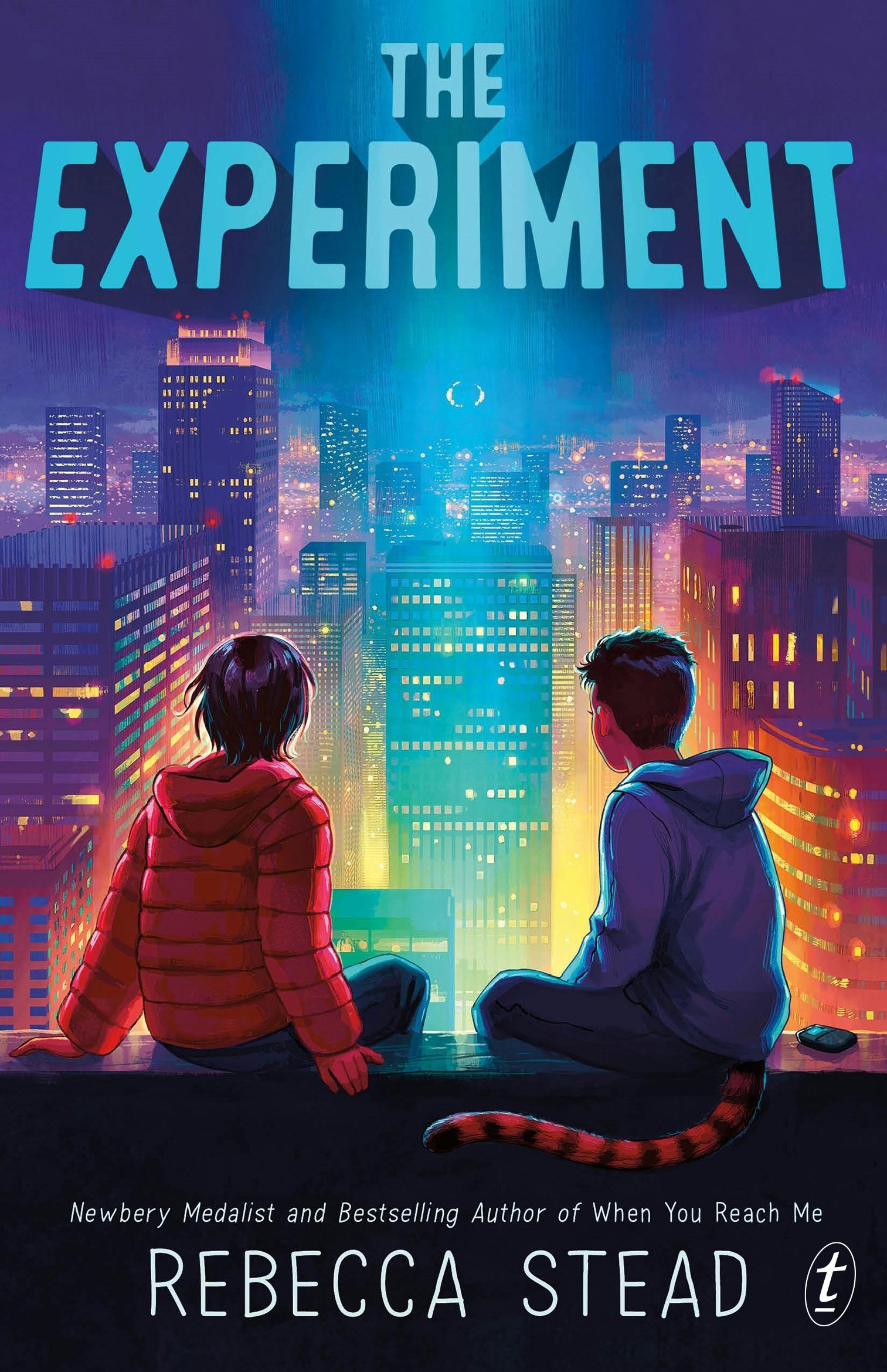

The Experiment by Rebecca Stead $22

Nathan never understood what was 'fun' about secrets, probably because he's always had to keep a very big one, even from his best friend, Victor. Although he appears to be a typical intermediate-school kid, Nathan learned at an early age that his family is from another planet, and he's part of an experiment to work out how to behave like a human and blend in. But the experiment suddenly seems to be going wrong. Some of the other experimenters, including Nathan's first crush, Izzy, are disappearing without a word. After his family is called back to the mothership, Nathan begins to question everything he's been taught to believe about who he is and why he's on Earth. Can he, Victor and Izzy uncover the truth? The Experiment is a fast-paced adventure — with aliens — that asks universal questions about how we figure out who we want to be, whether it's ever too late to change, and the importance of friendship. [Paperback]

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

New books for a new year! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

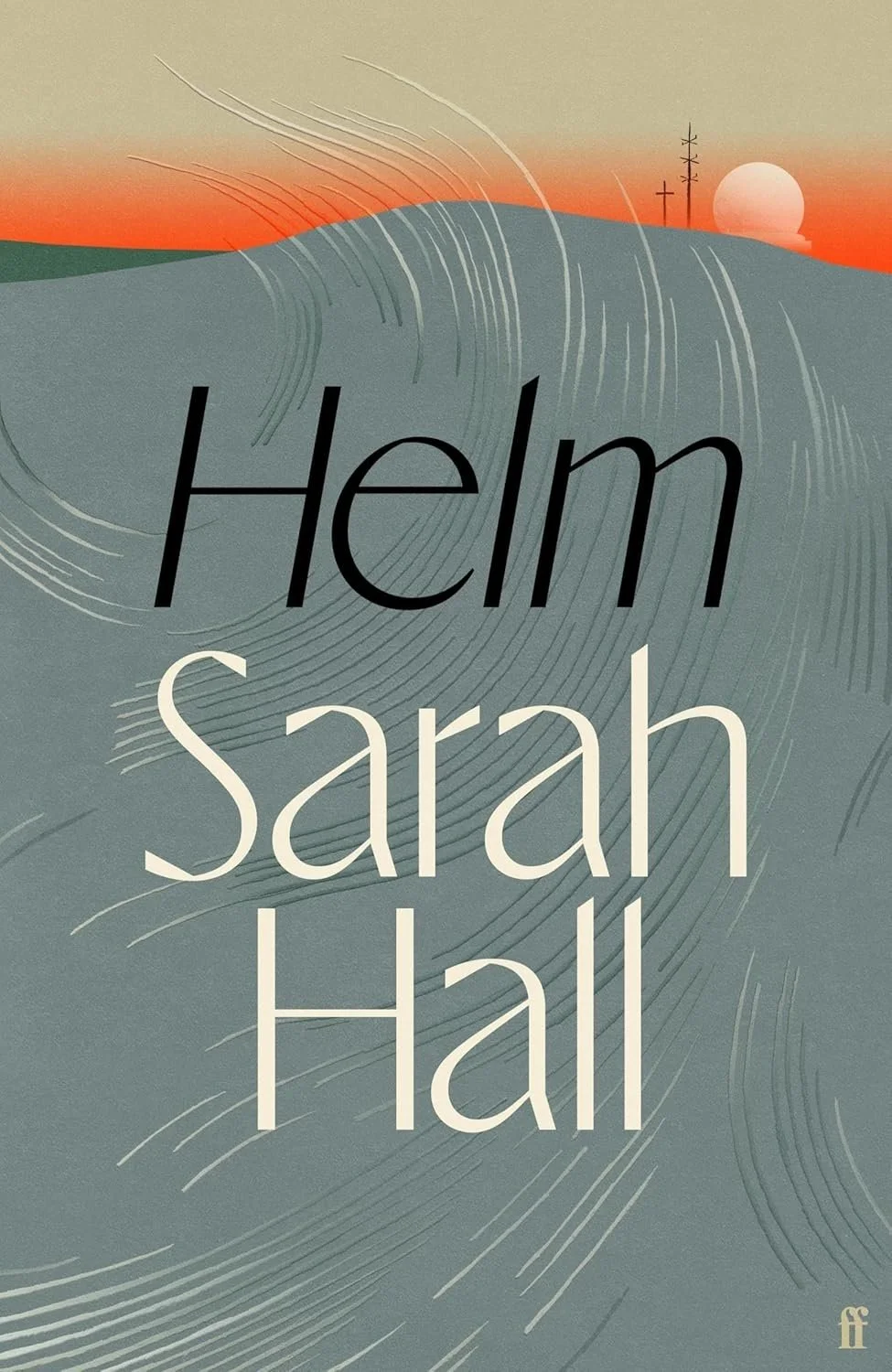

Helm by Sarah Hall $38

Helm is a ferocious, mischievous wind — a subject of folklore and wonder, who has blasted the sublime landscape of the Eden Valley since the very dawn of time. This is Helm's life story, formed from the chronicles of those the wind enchanted: the Neolithic tribe who tried to placate it, the Dark Age wizard priest who wanted to banish it, the Victorian steam engineer who attempted to capture it - and the farmer's daughter who fell in love. But now Dr Selima Sutar, surrounded by measuring instruments, alone in her observation hut, fears the end is nigh. Rich, wild and vital, Helm is the elemental tale of a unique life force — and of a relationship: between nature and people, neither of whom can weather life without the other. [Paperback]

”Hall makes language shimmer and burn.” —Damon Galgut

”No one writes like Sarah Hall.” —Sarah Perry

”I can think of no other British writer whose talent so consistently thrills, surprises and staggers.” —Benjamin Myers

”A wondrous, elemental novel from a writer of show-stopping genius.” —Guardian

”Hall's writing is alchemical, magnificent, divine, bodily. Here are new ways to understand what it feels like to be human. Here are books to cherish. I lay myself at the altar of everything Hall writes.” —Daisy Johnson

>>The wind was like a childhood friend.

>>Slow motion.

Slanting Towards the Sea by Lidija Hilje $28

Spanning across twenty years and one life-altering summer in Croatia, Slanting Towards the Sea is at once an unforgettable love story and a powerful exploration of what it means to come of age in a country younger than oneself. Ivona divorced the love of her life, Vlaho, a decade ago. They met as students at the turn of the millennium, when newly democratic Croatia was alive with hope and promise. But the challenges of living in a burgeoning country extinguished Ivona's dreams one after another — and a devastating secret forced her to set him free. Now Vlaho is remarried and a proud father of two, while Ivona's life has taken a downward turn. In her thirties, she has returned to her childhood home to care for her ailing father. Bewildered by life's disappointments, she finds solace in reconnecting with Vlaho and is welcomed into his family by his spirited new wife, Marina. But when a new man enters Ivona's life, the carefully cultivated dynamic between the three is disrupted, forcing a reckoning for all involved.

Set against the mesmerizing Croatian coastline, Slanting Towards the Sea is a cinematic, emotionally searing debut about the fragile nature of potential and the transcendence of love. [Paperback with French flaps]

”With illuminating prose and gripping storytelling, Lidija Hilje ascertains her place as an exciting new voice in world's literature. Slanting Towards the Sea is a love letter to Croatia and to anyone who dares to dream.” —Nguyen Phan Que Mai

”Oh, what a beautiful book this is — deeply felt, humane, gorgeously written. Hilje's prose is positively hypnotic — I sunk in and didn't want to come up for air.” —Claire Lombardo

>>Trying and failing to write a universal story.

The Devil Book by Asta Olivia Nordenhof (translated from Danish by Caroline Waight) $38

A classic girl-meets-boy-meets-devil story. A woman meets a man on a train in Copenhagen and agrees to visit him in London. While she sits out a two-week Covid quarantine in his apartment, she begins to tell her story. Years ago and desperate for money, she sold herself to a stranger called T. He offered her a suitcase full of money and lavish gifts in exchange for total control of her body. In the bed between them lay a large kitchen knife and the promise of an iconic death. But at the last moment, she aborted the treacherous game and fled. Now in London, she reflects on the forces — financial and social — that led her to the brink of destruction, and wonders what it would take to believe in love again. Frank, intimate and dazzling entertaining, The Devil Book takes us from Copenhagen to London to the inside of a mental institution, as well as a fancy apartment block, this unmissable stand-alone novel is the follow up to the critically-acclaimed Money to Burn. [Hardback]

”Covering much of the same ground as her last novel — the interrelation between money, sex, violence and gender, capital's power to console or benumb — The Devil Book shares the same bristling, didactic prose, but with a welcome barbed humour. a lacerating literary harnessing of rage at a decrepit system, held together by Nordenhof's defiantly unique voice.” —Financial Times

>>Writing as a political act.

>>Money to Burn.

Portrait of an Island on Fire by Ariel Saramandi $45

A deeply moving and revelatory reading experience, the essays collected in Portrait of an Island on Fire form a searing account of Mauritius at a crucial moment in its history. Unceasing in its critiques of racist, patriarchal abuses of power, in its unpicking of the ills at the core of contemporary Mauritian society and their roots, the collection is a milestone in thinking about the lasting social and political effects of colonialism and how they play out at the level of government policy, the handling of environmental issues, in schools, in hospitals, in families, in language. For all its well-placed anger, Ariel Saramandi’s sparklingly intelligent and intimate debut is full of love and momentum – a push for a better future for Mauritius and, by extension, for the world. [Paperback with French flaps]

”Ariel Saramandi's interweaving essay collection presents a courageous, stringent and mesmerizing portrait of the island, her home, and the social and political effects of colonialism. She's a great writer.” —Wendy Erskine, The Observer

”Portrait of an Island on Fire is a fascinating look at Mauritius, a personal account of a homeland told with rage, rigour and love. Saramandi brilliantly, subtly teases out the threads of Mauritian history, politics and culture, honouring both the particularities of this unique place and showing the troubled connections — rapacious capitalism, racism, creeping authoritarianism, right-wing paranoia — that seem to stretch across the whole of our fragile planet. This is a beautifully written book of deep knowledge, righteous anger and fierce hope.'“ —Lydia Kiesling, author of Mobility

”Ariel Saramandi is a courageous and mesmerising new voice, a chronicler of contemporary Mauritius whose writing refracts the influences of her Mauritian compatriots, Ananda Devi, Nathacha Appanah and Shenaz Patel in French, Lindsey Collen in English, in a voice which is wholly her own. Portrait of an Island on Fire unpicks the knots of Mauritius's entangled histories — of plantation slavery, of indentured labour, of colonisation, of communalism and patriarchy — laying out the threads which make up her own history of ancestral oppression and structure her lived experience of privilege and pain; which form the fabric of contemporary capitalist Mauritius, and its particular intersections of race, class, gender, and language - its politics - and its particular forms of the white supremacy, anti-Blackness and toxic masculinity acted out on the bodies of those without power the world over. Saramandi is laser-focused in her rage, joyful in both her refusal to look away, and in her insistence on what sustains her: writing, motherhood, her marriage, friendships, community - and the beauty of her island.” —Natasha Soobramanien, co-author of Diego Garcia

False War by Carlos Manuel Álvarez (translated by Natasha Wimmer) $37

What is the difference between an immigrant, someone living in exile, and a refugee? The characters in False War are ambivalent castaways living lives of deep estrangement from their home country, stranded in an existential no-man’s land. Some of them want to leave and can’t, others left and never quite finished getting anywhere. In this choral novel, employing a dazzling range of narrative styles from noir to autofiction, Carlos Manuel Álvarez brings together a series of interconnected stories of the perennially displaced. From Havana to Mexico City to Miami, from New York to Paris to Berlin, whether toiling in a barber shop, lost in the Louvre, competing in a chess hall in Cuba, plotting a theft, or on a trip for émigré dissidents, these characters learn that while they may appear to be on the move, in reality they are paralysed, living in permanent stasis. With a fractured narrative that brilliantly reflects the disintegration that comes with uprooting, full of tenderness, disenchantment and melancholy, False War is an extraordinary novel that confirms Carlos Manuel Álvarez as one of the indispensable voices of his generation. [Paperback with French flaps]

”Carlos Manuel Álvarez’s second novel is a hugely rewarding, polyphonic narrative of migration from Cuba. Through its characters’ rich and eccentric interior worlds, it gives articulation to people whose lives are often reduced to stereotypes and offers a new vision of migration. False War is a rich and capacious novel that has much to say about our contemporary moment.” — Arin Keeble, Guardian

”Álvarez has not fashioned a linear story, but braided these threads together into a polyphonic motet of voices that are alternately sardonic, weary and, above all, angry. It is a tribute to Wimmer’s peerless translation that she effortlessly captures their range, cadence, humour and rage. False War is a poignant study of exile and exclusion, one that avoids the easy tropes of nostalgia and sentimentality: for Álvarez, exile is not an escape but a condition – permanent, internal and profoundly personal.” —Frank Wynne, Irish Times

”I was blown away by this novel. Nothing in the story is reducible. Its formal ambition is met by its execution, and the effect is staggering. Álvarez is an immense writer, a generational talent, and this, for me, is a generation-defining work.” — Michael Magee

Good Girl by Aria Aber $37

In Berlin's underground, where techno rattles buildings still scarred with the violence of the last century, nineteen-year-old Nila finds her tribe. In their company she can escape the parallel city that made her, the public housing block packed with refugees and immigrants, where the bathrooms are infested with silverfish and the walls outside are graffitied with swastikas. Escaping into the clubs, Nila tries to outrun the shadow of her dead mother, once a feminist revolutionary; her catatonic, defeated father; and the cab-driver uncles who seem to idle on every corner. To anyone who asks, her family is Greek, not Afghani. And then Nila meets American writer Marlowe Woods, whose literary celebrity, though fading, opens her eyes to a world of patrons and festivals, one that imbues her dreams of life as an artist with new possibility. But as she finds herself drawn further into his orbit and ugly, barely submerged tensions begin to roil and claw beneath the city's cosmopolitan veneer, everything she hopes for, hates, and believes about herself will be challenged. [Paperback]

”Aber touches the heart of a young woman struggling to find herself in the heat of clashing cultures ... You'll be immediately arrested by the haunting beauty of her work and the way desire pushes against the seams of despair.” —Washington Post

”At heart, the novel is about the allure of freedom and the estrangement from others that is the cost of both exile and artistic creation. Aber writes with the masterful precision of an archivist. Exile, migration, displacement: These will splinter even the most solid self. But out of the shards, it is possible to make art, as Nila finally realizes — and as Aber has done in this touching novel.” —The Atlantic

”Captures the ache of Muslim girlhood and the vertigo of never feeling quite at home. Aber ingests the millennial playbook and spits out something that happens to be more interesting.” —Vulture

>>Identity and exile.

My First Ikura: A story for growing girls and their whānau by Qiane Matata-Sipu and Isobel Joy Te Aho-White $30

Rooted in te ao Māori, My First Ikura is a beautifully illustrated children’s book that follows a young girl’s first period, guided by the support of her whānau. More than a story of physical change, it celebrates womanhood as a sacred rite of passage. Addresses first menstruation through a Māori cultural framework. Emphasises ceremony, family support and ancestral wisdom — also includes a specially written karakia for families to learn together. Nicely illustrated and produced. [Hardback]

>>Look inside.

Crucible of Light: Islam and the forging of Europe from the 8th to the 21st century by Elizabeth Drayson $45

Drayson pulls together the epic interwoven history of the Muslim and Christian worlds over an 800-year span, taking in the conquest and re-conquest of Spain, the meteoric rise of Arabo-Norman Sicily, the Ottoman renaissance of the 16th to 18th centuries, the ebb and flow of Balkan history and the fate of contested islands like Cyprus and Malta, with their very different outcomes. Focusing on major turning points, individual stories and key places, from Mecca to Cordoba, from Damascus to Venice, and from Vienna to Istanbul, Drayson tracks unifying themes — classical learning preserved in Islamic libraries, the enduring influence of Moorish architecture and design, the food, the goods traded and the continuing discourse between individuals and cultures that has permeated Europe's history and shaped its borders. Drayson also explores the growing dialogue between Muslims and Christians across Europe today, a dialogue prefigured in the history of medieval and early modern Europe, in which harmony and enlightenment rise above perennial conflicts. These ideas challenge the way contemporary European identity is defined and point to the vital impact of Islamic civilisation upon the continent. Surprisingly few people are aware of how much Europe owes to its Islamic heritage except via pockets of tourism, and this book aims to correct that while exploring the endless complexities that this vexed relationship throws up. At a time when Islam is so narrowly identified with terrorism and migration in Europe it is a necessary corrective. [Paperback]

Taco (‘Object Lessons’ series) by Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado $23

Taco is a deep dive into the most iconic Mexican food from the perspective of a Mexico City native. In a narrative that moves from Mexico to the United States and back, Sánchez Prado discusses the definition of the taco, the question of the tortilla and the taco shell, and the existence of the taco as a modern social touchstone that has been shaped by history and geography. Challenging the idea of centrality and authenticity, Sánchez Prado shows instead that the taco is a contemporary, transcultural food that has always been subject to transformation. [Paperback with French flaps]

>>Other books in the ‘Object Lessons’ series.

Physics for Cats: Science cartoons by Tom Gauld $38

What happens to a cat who goes through a wormhole? Find out why every scientist worth their sodium chloride has a Tom Gauld cartoon taped to their electron microscope. This new batch of hilarious gags will be as important to every self-respecting scientist as a lab coat and goggles and oversize rubber gloves. Find out what the hadron's news alert about CERN says! Everyone asks, "What is dark matter?" and "Where is dark matter?" but do they ever take the time to ask, "How is dark matter?" Based all on previous data, we can predict with a 99.99% certainty that you will either laugh, guffaw, chortle or snort (we don't have a large enough sample set to be able to say which particular type of mirth you will experience). [Hardback]

>>Look inside!

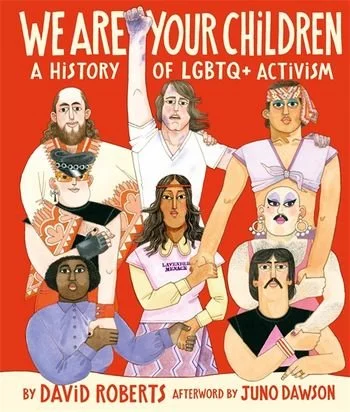

We Are Your Children: A history of LGBTQ+ activism by David Roberts $65

A gorgeously illustrated, accessible celebration of queer activism, by the creator of the award-winning Suffragette, David Roberts. With an afterword by Juno Dawson. Touching on major moments in the story of the fight for LGBTQ+ rights including the Stonewall Uprising, the first Gay Pride Rally and the dazzling history of drag and the ballroom scene, We Are Your Children is a wide-ranging and inclusive account of a multifaceted movement, with detailed and characterful colour artwork. This book showcases figures from queer history like Harvey Milk, Julian Hows, Carla Toney, Crystal LaBeija, We Wha, Vincent Jones, Marsha P. Johnson, Alan Turing, Sylvia Rivera and many more. From the secret slang adopted by gay Londoners in the 60s, to the decades of sit-ins and marches, there are countless fascinating stories to be told: stories of resistance, friendship, love, fear, division, unity and astonishing perseverance in the face of discrimination and oppression. Encyclopedic in scope, this will expand anyone’s knowledge and understanding. [Hardback]

>>Look inside!

Twenty at Twenty!

Top up your summer reading pile with a selection of twenty outstanding books at a sweet price.

Head to the website now and make your selection.

Enter the discount code READ when adding the books to your cart for a 20% discount.

Limited time!

The Readers’ Carousel offer is extended until 6 January 2026, and is limited to the copies currently in stock.

Read our latest newsletter.

19 December 2025

It is not too late to get your books before Christmas — either as gifts or for your own summer reading.