INCOMPLETELY UNWRITTEN — an interview with Thomas Pors Koed [...] ELLIPSIS

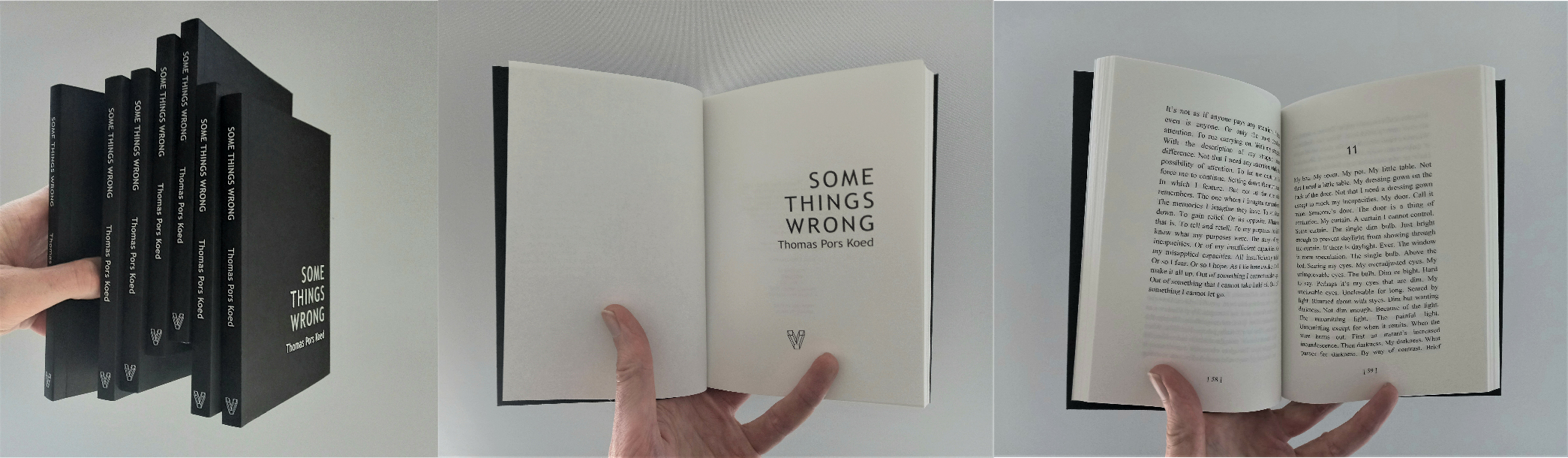

Thomas Pors Koed is the author of

SOME THINGS WRONG (published by Volume Editions).

This interview was conducted by ELLIPSIS in April 2024.

It has been edited slightly for clarity and concision.

Ellipsis: Thank you for agreeing to this interview. I know you weren’t very keen on doing it.

TPK: Well, I suppose doing it is better than anticipating it, and also better than — inevitably — regretting it.

Ellipsis: Well, we’re in a sweet spot. We will begin in just a moment. By the way, is there anything that you don’t want to be asked about in the interview?

TPK: Just no biographical questions.

Ellipsis: OK.

TPK: And, therefore, no biographical answers…

Ellipsis: Fair enough. Let’s begin.

. . . . .

Ellipsis: You have described yourself — or, at any rate, you are described on the cover of the book — as a writer of “unpopular fiction”. Is that original, creative, elitist, or what? Please explain.

TPK: I am suspicious of the concept of originality, as I am suspicious of the related concept of creativity.

Ellipsis: Even in literary expression?

TPK: Although people do from time to time express themselves — whatever that means — in words, that does not comprise literature. I am not interested in self-expression. What we call originality is anyway generally little more than a failure of imitation — we try to imitate but we fall short. The greater the failure, the greater the originality.

Ellipsis: Are you telling me that there is something original about failure? I would have said most failures are pretty similar…

TPK: There is an expectation and an inclination that writers, for instance, will strive towards an apogee of quality as defined by the market, or the academy, or the literary idol, or the support group, or some such arbiter, and a few do progress towards this, to their peril…

Ellipsis: And the rest are marginalised merely by lack of talent?

TPK: Perhaps. But they are still affirming what they will never attain.

Ellipsis: All successes might tend towards being the same, but does that mean that all failures fail in their own beautiful way? That’s not my experience. Are you thinking of failure as a method or as a consequence?

TPK: Almost all genetic mutations are nonviable, but a very few enable an evolutionary leap. Failure is a pretty good method, if an unavoidable consequence can be said to be a method, at least initially, and pretty much unavoidably. If you don’t fail, you’re doing it wrong.

Ellipsis: Are there other methods of subverting one’s own best attempts at imitation?

TPK: It is necessary to employ other methods more frequently as one’s ability to imitate increases, as one becomes more skilled, if that’s the word, at imitation.

Ellipsis: And what are the methods?

TPK: The simplest of these methods, and in many ways the cleanest and often the most effective, but also the laziest, is simple inversion…

Ellipsis: Like “unpopular fiction”?

TPK: To invert a statement is both to preserve and to critique that statement, and, more importantly, or at least more interestingly, both to employ and to interrogate the means by which that statement is produced. I am far more interested in the mechanisms of language than in its so-called content. How something is expressed, its form if you like, carries more meaning than what is expressed. Or, rather, how something is expressed is fundamentally what is expressed.

Ellipsis: Does meaning, then, have more to do with grammar than with lexis?

TPK: Lexis can be dumped and exchanged but grammar determines the way that an idea is put together. Grammar is foundational to what we call consciousness, independently of and precursory to anything we might be conscious of. If we think of language as the relation between elements — such as words — rather than the elements themselves — which are relatively interchangeable — we can better question how language operates and is acquired, and how it correlates with other relational aspects of what we might call existence, which, I suppose, are also forms of grammar…

Ellipsis: And hence editable!

TPK: Artificial Intelligence has very little to do with computer technology — that’s just frightening amounts of processing power serving someone’s interests — but everything to do with the algorithms inherent in language, or in other relational systems. We all already do what we aspire or fear for computers to do — we use the algorithms inherent in language, and our life-long ‘training’ in what we might call a data set of language experiences, to generate language artifacts, so to call them, or language products — if we prefer terminology that considers them system outputs: texts, speech, whatever — that pass as appropriate to the circumstances in which we generate them. In fact, these language products are generated, most of the time, almost entirely by the circumstances in which they occur, with very little input from us — they are acts of mimesis or camouflage.

Ellipsis: And the better we get at them the less original we are?

TPK: The less we fail at camouflage, the less personality we have. If, that is, personality is dependent on shareability.

Ellipsis: And the more we succeed?

TPK: The concept of linear perfectibility, which is a fairly pervasive concept, makes things more similar. It entails a loss of diversity, a loss of individuality, a loss of potential — given that most potential inherent in any particular set of circumstances is what would be dismissed as sub-optimal — and tends towards a monoculture. A chess computer or a grand master knows the absolute best move in any arrangement of pieces on a chess board, and we can train ourselves or be trained to improve our recognition of these moves and thereby of our chess play, to better mimic the optimum, but this leads to a kind of deterministic approach.

Ellipsis: Two ultimate chess computers playing each other would play the same game every time!

TPK: And the better a computer gets at producing literature, and the closer it approaches the aggregate optimal, the less interesting that literature will inevitably become.

Ellipsis: Just like with human authors…

TPK: So to be creative or interesting or not-boring or whatever, there need to be some failure circuits in the algorithm, or some arbitrary constraints upon the mimesis, some bias towards the sub-optimal — it is the same for computers as for people — and I suppose such a thing might be possible for a computer, I don’t know. The problem for the computer would be in deciding which few failures to run with and which many failures to cast aside. As you said, most failures are best abandoned. This is something that human writers get better at as they become better writers — better at resisting the algorithm and yet still writing — but something that goes against what computers are trained and are supposedly training themselves to do. They are trained to affirm the algorithm.

Ellipsis: Just like most of us, most of the time?

TPK: Well, yes. But we are better at failing, or at least better at failing in a particularly human way. To pass as human one must fail an inverse Turing test.

Ellipsis: At least occasionally.

TPK: Personhood only happens to us occasionally.

Ellipsis: Is it possible for a computer to simultaneously entertain contrary impulses in the way that humans seem entirely able to do, or cannot seemingly avoid doing?

TPK. There lies the path to personhood.

Ellipsis: How does this relate to Some Things Wrong? Does this relate to Some Things Wrong?

TPK: Hmm. Some Things Wrong is an unsparing yet strangely cheerful exploration of failure, error and incapacity.

Ellipsis: You’re reading from the blurb.

TPK: Well, yes. The purpose of a blurb is to deflect questions about a book’s contents while simultaneously suggesting that the answers to these questions might lie within the book.

Ellipsis: I will rephrase my question, more carefully. How does the form of the book relate to its content?

TPK: Some Things Wrong did originate as an attempt to write a novel with characters, plot, setting, temporal unity, all those novelistic crutches, but all these things got in the way of what I was interested in — the production of text — so I set myself the task of getting rid of them as much as possible. Some Things Wrong was an attempt to reduce the content to see what the language mechanism does running on empty or on something near empty. What are the basic semantic implications of the mechanism itself?

Ellipsis: But just full stops! Why?

TPK: I thought that it would be presumptuous of me to attempt other punctuation until I had begun to understand the most fundamental of them. The question I was most interested in when writing this book, in both a literary or linguistic sense and in a wider so-to-call-it existential sense, was: When we come to a place where stopping is possible or unavoidable, what is it that allows us or compels us to continue?

Ellipsis: That’s from the blurb again!

TPK: We, or at least I, experience intense ambivalence about this stopping/carrying on issue. It is inherent in every moment of your life, or rather, between the moments, and, once I started to think about it, it was inherent in every full stop of every sentence that I read or wrote.

Ellipsis: What does it mean, to carry on?

TPK: Carrying on after a full stop is not the same as just continuing as if the full stop wasn’t there. For me, every statement provokes a reaction to that statement, a calling-into-question of that statement, an undermining of that statement, a movement in the other direction. Everything that is stated is unavoidably a sort of exaggeration or oversimplification, and, when I think about it, it appears unavoidably ludicrous and I feel an immediate impulse to correct or annul or interrogate or complicate that statement. A full stop is a pivot about which this impulse can be exercised.

Ellipsis: Something carries us through a full stop, but the world is somehow altered by that? Disconcerting!

TPK: Maybe this is the way that all text is produced, and in which all moments are produced.

Ellipsis: Many times in the book, even relatively simple actions are broken down into their most basic parts and carefully described, most painfully, perhaps, in the final chapter, if I’m right to call it a chapter, but, really, in all the other chapters, too, Chapter 2, for instance, memorably. Why do you do this?

TPK: I am what you might call a reluctant exister. Being alive is difficult. It is only possible, for me anyway, if I can do it as a series of micro-activities.

Ellipsis: Or it presents itself as a series of micro-obstacles?

TPK: Tiring to overcome, but more achievable than confronting anything approaching the maximal total obstacle we might call, rather vaguely, my life. Literature, as well, exists only to the extent that the maximal is broken down into a series of details or moments.

Ellipsis: Is this a useful strategy for going on, or whatever we choose to call it?

TPK: When everything is impossible, only the very smallest thing has anything approaching a withstandable amount of impossibility. The very smallest thing is the least impossible. Writing and living are similar, in this regard.

Ellipsis: I have often wondered, can literature, or the production of literature, show us a way to overcome or cope with depression?

TPK: Depression, from my experience, is what could be termed a time problem. Fiction is also a time problem, but there are a number of ways of gaining traction on this time problem in fiction, both as a writer and as a reader. I do not believe that these ways of gaining traction on the time problem of fiction would be useful for gaining traction on the time problem of depression, but it is good to entertain the very slight possibility that they might be.

Ellipsis: Is literature reassuring, I mean inherently, despite whatever its content may be?

TPK: I wouldn’t say that, but literature does have at least some sort of forward momentum that can carry you through.

Ellipsis: Through every full stop?

TPK: Except the last one.

Ellipsis: Is it that desperate?

TPK: I don’t believe in redemption.

Ellipsis: And yet Some Things Wrong is funny.

TPK: The melodrama of existence is inherently ludicrous. You are probably better off to find that funny than not.

Ellipsis: Would a comma help, do you think?

TPK: Some Things Wrong is a book about the operative potential of full stops. Full stops are always on the same level. If I write another book, which I am trying to avoid, it might be about the operative potential of commas. I have been trying out commas since I finished Some Things Wrong. Commas expand moments, they postpone full stops, they allow nested clauses that permit several simultaneous levels of narrative or time or voice or point of view or whatever to exist inside each other, the large inside the small. Commas are transgressive and beautiful in a way that full stops just aren’t.

Ellipsis: Throughout the book, a character, if I can call them that, seems often to be incapacitated not only by circumstance but maybe by illness. Why is that? Is it illness?

TPK: I am slightly interested in the relationship between illness and literary form. Illness — in my case ME, or what we could call chronic systemic dysregulation, which has affected me to various degrees for forty years, but really any illness — entirely alters your experience of time, and the granularity of your awareness of detail — time and detail being entirely the same thing in fiction. Illness necessitates a rethinking of the received drivers of both life and literature, it disestablishes narrative authority, it undermines your faith in blithe ongoingness, it instigates the creation of a surrogate self to carry some of the existential load that the ill person is otherwise incapable of sustaining. Illness corrodes and questions what could otherwise be called maybe the plot of your life.

Ellipsis: These all sound like useful things for writing fiction.

TPK: The tools come at the price of being incapable of using them. Or often incapable. An ill person’s life is at best necessarily a low-calibre life. Of course, everybody seems to want to choose a low-calibre life, there are a lot of good things about a low-calibre life, but the attraction of a low-calibre life lies in the choosing. An ill person doesn’t get to choose.

Ellipsis: You’ve carefully phrased that as a non-biographical statement!

TPK: I think I made some biographical statements a few minutes ago. Can we edit them out later?

Ellipsis: When and in what circumstances did you write Some Things Wrong?

TPK: I finished writing the book about ten years ago.

Ellipsis: In the years before commas?

TPK: Yes, in the first century BC.

Ellipsis: Or the first century BCE — Before the Covid Era!

TPK: Ha, yes. Before the zombification disease.

Ellipsis: And what has happened to it since then?

TPK: The manuscript was then subjected to various processes of unwriting: long periods of languishing and decay — the effects of extended periods in a desk drawer cannot be undervalued — and intense periods of revulsion and excision. The book is about a third the length it was ten years ago.

Ellipsis: Is that a good thing?

TPK: I would like to have unwritten it to the extent that it could have been printed on a postage stamp. Or until all that remained was a single full stop.

Ellipsis: Circumstances intervened and it got published!

TPK: Incompletely unwritten.

Ellipsis: You said that the book started out as a novel. Do you think of it as a novel?

TPK: A novel in the terminal stages of decay.

Ellipsis: Approaching the end of the book, Chapters 18 and 19, if they are chapters, are constructed entirely as dialogue, but it is not clear to me who the speakers are or what relationship they have to the content of their dialogue. Can you help me with this?

TPK: Do the speakers even exist other than as the words that are spoken?

Ellipsis: You’re asking me?

TPK: I think that what I was thinking back then when I thought that thought or at least the thought of thought might have been possible was of attempting — though necessarily failing — to build a model…

Ellipsis: A model as in a kind of toy?

TPK: …of consciousness that was transactional and nonunitary — these are not the right words — that was not predicated on the false concept of the mind or the self as an entity, but that rather considered consciousness only as — or as arising from — a grammatical relationship between participating elements. Because Some Things Wrong was an attempted experiment in seeing what could be done without, these two dialogues were reduced as far as possible to the simplest interactions between Assertion and Interrogation — so to call them — which I at that time postulated as the last irreducibles — voices tending to an aporia that somehow still contained enough energy to spill the text — or consciousness — over beyond each full stop.

Ellipsis: Life or Invention?

TPK: No privilege or credence is given to either. The two voices — if they are two — as far as possible are characterless — characteristicless — apart from the impulse they voice. I had lost interest — or confidence — in content and was finding meaning only in grammar.

Ellipsis: Does grammar create its own content? Ex nihilo? Or where does content come from?

TPK: The ideal text for me at that time was one that contained no ideas other than those unknowingly brought to it by the reader.

Ellipsis: Can literature make the world better? The world is full of troubles and problems, crying out for solutions or at least attention. Obviously, or presumably, you are aware of these. Does Some Things Wrong address these things, things that are so obviously wrong and so obviously need addressing? If so, how?

TPK: Hmm. Fascism and Capitalism both realise that language is the fundamental battleground. They understand that they can’t destroy democracy or self-determination or diversity unless they first destroy language. Viktor Klemperer wrote about how he had observed the Nazis distorting language in the 1930s, obfuscating meaning and limiting thought through, for example, the use of buzzwords, and you can see the same tactics being employed by the right today.

Ellipsis: For example?

TPK: Well, for example, the ugly buzzword ‘woke’ is used as a pejorative adjective, often applied to things that it would be hard to make look bad without it, but, if the speaker had no recourse but to say in plain language what they actually meant, the speaker would appear either ludicrous or dangerous — or both ludicrous and dangerous, which is usually the case —and the particulars of the given situation could be more clearly perceived and discussed. Klemperer said that the first step in fighting fascism is to challenge the use of buzzwords, to re-establish the content of discourse, to rescue the particular from the tired phrase, from the generalisation, from the cliché, from the stereotype, from the slur...

Ellipsis: Does this relate to your book?

TPK: Only in that I tried to bring to every statement therein a rigorous challenge — to what is being said, to how it is being said — to make the reader aware of the extent to which their understanding is being shaped by the way language is being used.

Ellipsis: Is that empowering?

TPK: All relations are relations of power. Grammar is the template.

Ellipsis: So, people, rise up! Edit your way to equality and freedom!

TPK: Quite.

Ellipsis: But you don’t actually address any of the pressing issues of our time, and surely if we are in an emergency — whether that’s climate change or genocide or bigotry or mass illness or the subversion of discourse by far-right actors or whatever — we should treat it as an emergency and not just call it an emergency. If you come across an emergency surely you do everything you can to address that before you even think of doing anything else. What is literature’s role in a time of emergency? If writing is your thing, what should you be writing?

TPK: Challenge accepted.

Ellipsis: What you said before, about the right using buzzwords, clichés, doublespeak, stock phrases and so on, to prevent thought, and how you seem to feel that you have a mission…

TPK: Humph.

Ellipsis: …to remove these obstacles to free discourse, or empathy, or understanding, or whatever, and yes, no doubt, that is a noble mission, but perhaps people don’t really want to think because thought is so painful, thought is so hard. Maybe the release from thought is the appeal of the right: it’s wrong but it’s easy, compared with the hard burden of thought that characterises the left — the ceaseless striving to get things right, to make things right, in a world in which that seems closer and closer to impossible.

TPK: All the more reason to try. Only the impossible is worth the effort.

Ellipsis: However self-destructive that may be? Should the left perhaps be employing — and maybe they even are employing — buzzwords of their own, stock phrases, stereotypes, and all the rest, to relieve people of thought and yet to move the world to a better place?

TPK: Would that be a better place? The ends are the products of the means. In fact, there are only means.

Ellipsis: Do you think there actually are people who want to subject themselves — as participants of the world or as readers of books like your book — to the rigours that seem to be expected of them to be aware participants or aware readers? — if aware is the right word in either case.

TPK: Maybe you just answered your first question, about “unpopular fiction”…

[Interview by A.S. et al]