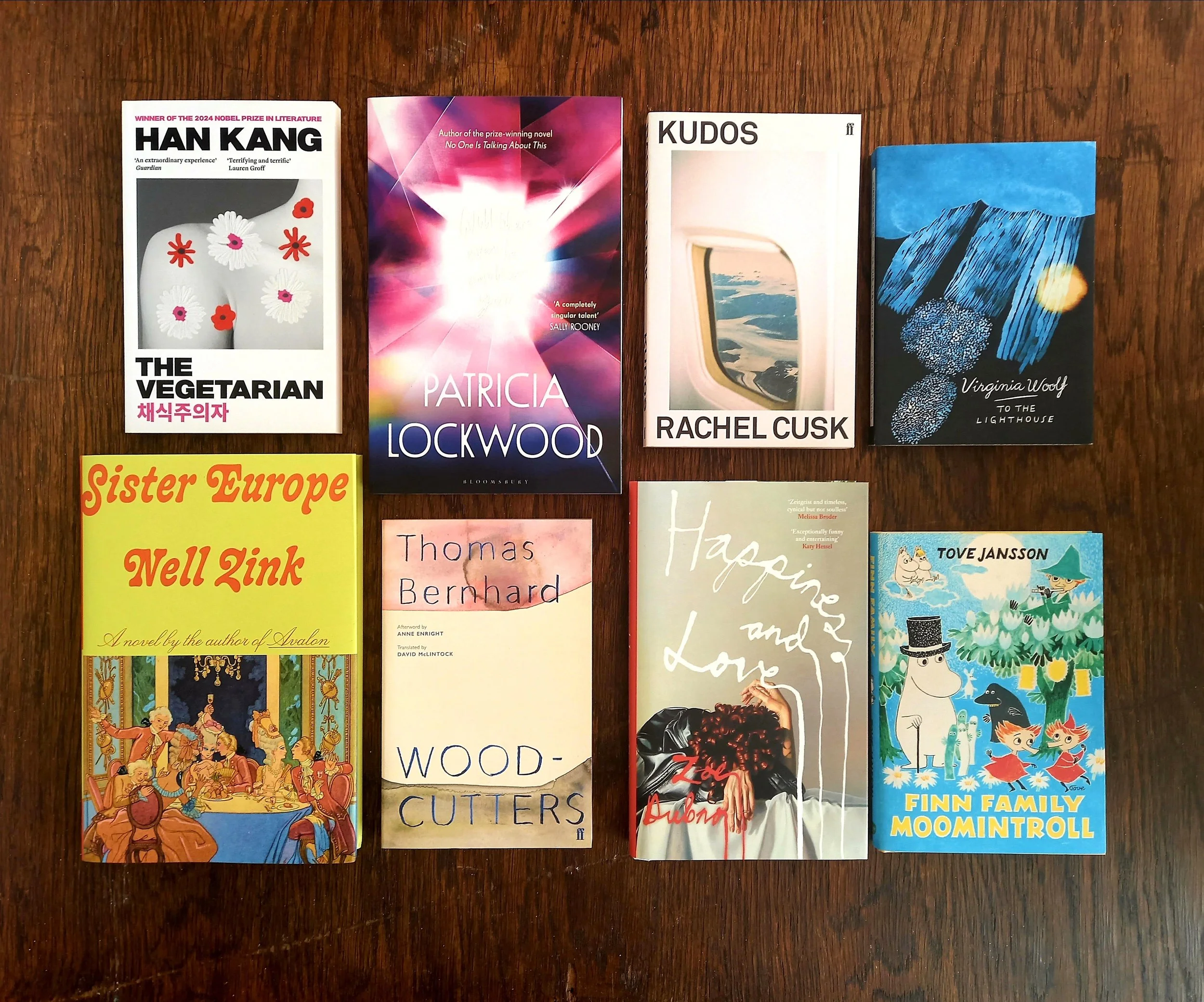

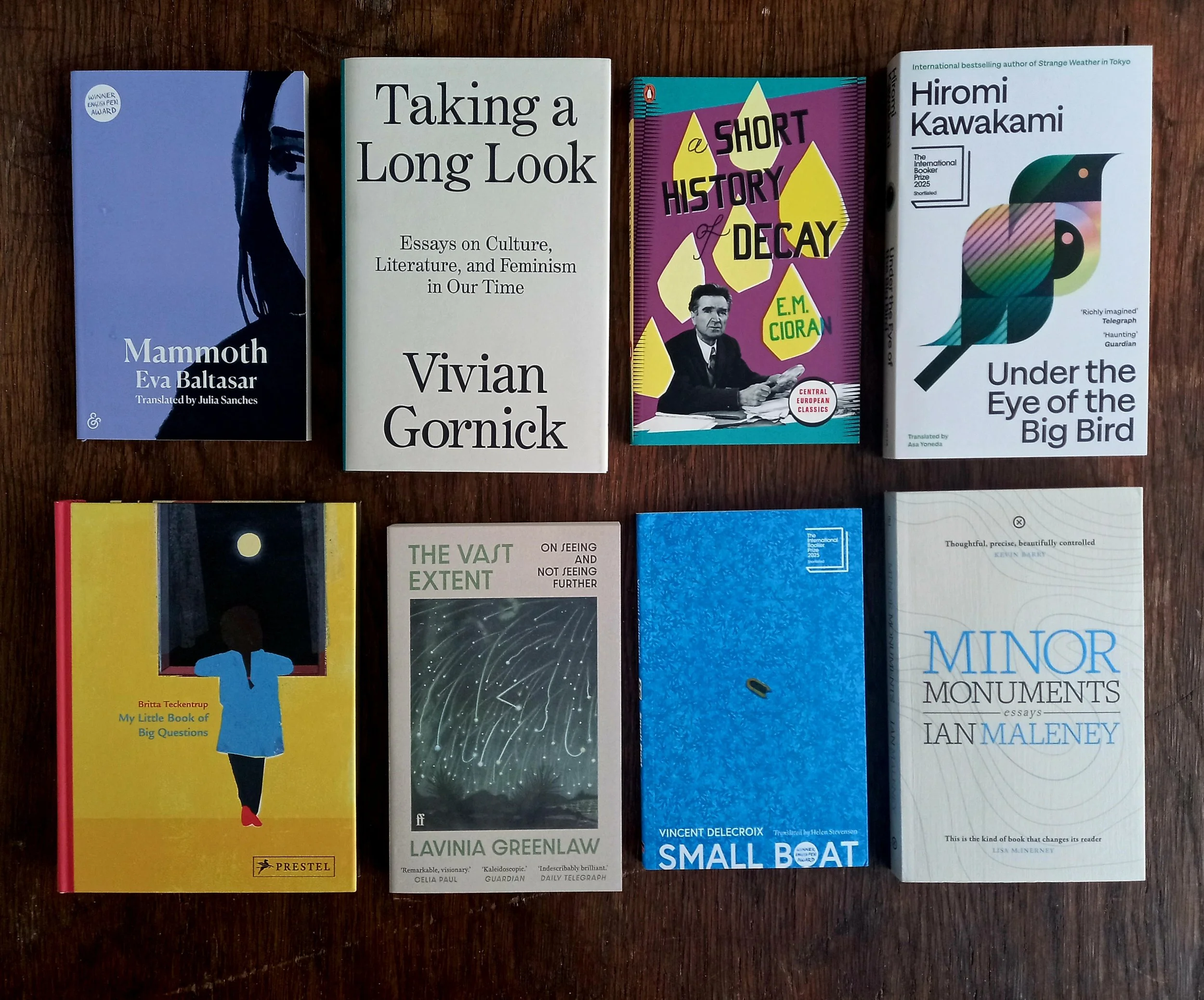

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

All your choices are good! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

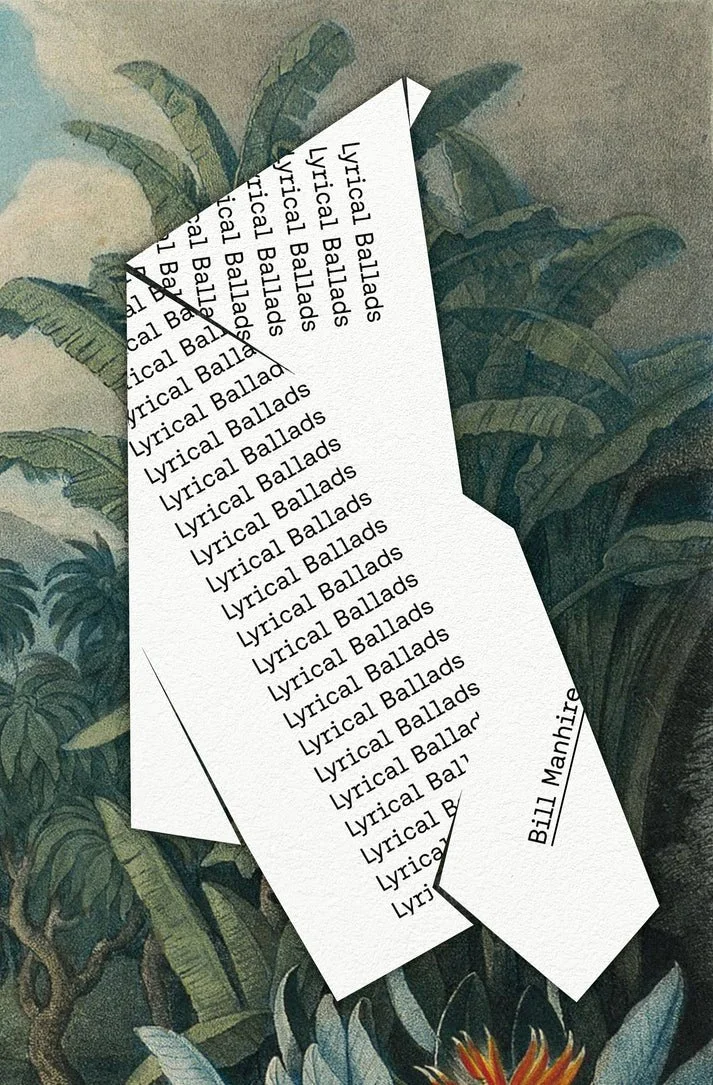

Lyrical Ballads by Bill Manhire $30

Bill Manhire has always subscribed to Paul Valéry’s definition of poetry as ‘a prolonged hesitation between sound and sense’. In that spirit, many of the poems in this long-awaited new collection blend story and song, and do so using everyday words and phrases that — suddenly, on the page — become new and delightfully weird. Lyrical Ballads is a many-peopled collection: the baffled inhabitants of Every Street and Intermediate Street are here, while Dracula, T.S. Eliot and Bobby Outram from Outram have walk-on parts. The collection is anchored by two long sequences that embrace awkwardness, mystery and absurdity: ‘The Tobacco Tin’, a kind of folk story riding along on its own lacunae, and ‘Tell You What’, a set of curmudgeonly opinions that evoke the prejudices of a fast-vanishing world. As they notice the small collisions between wonder and everyday reality, and the trajectories of those who don’t fit easily in this world, these poems close in on the darker certainties of our lives. [Paperback]

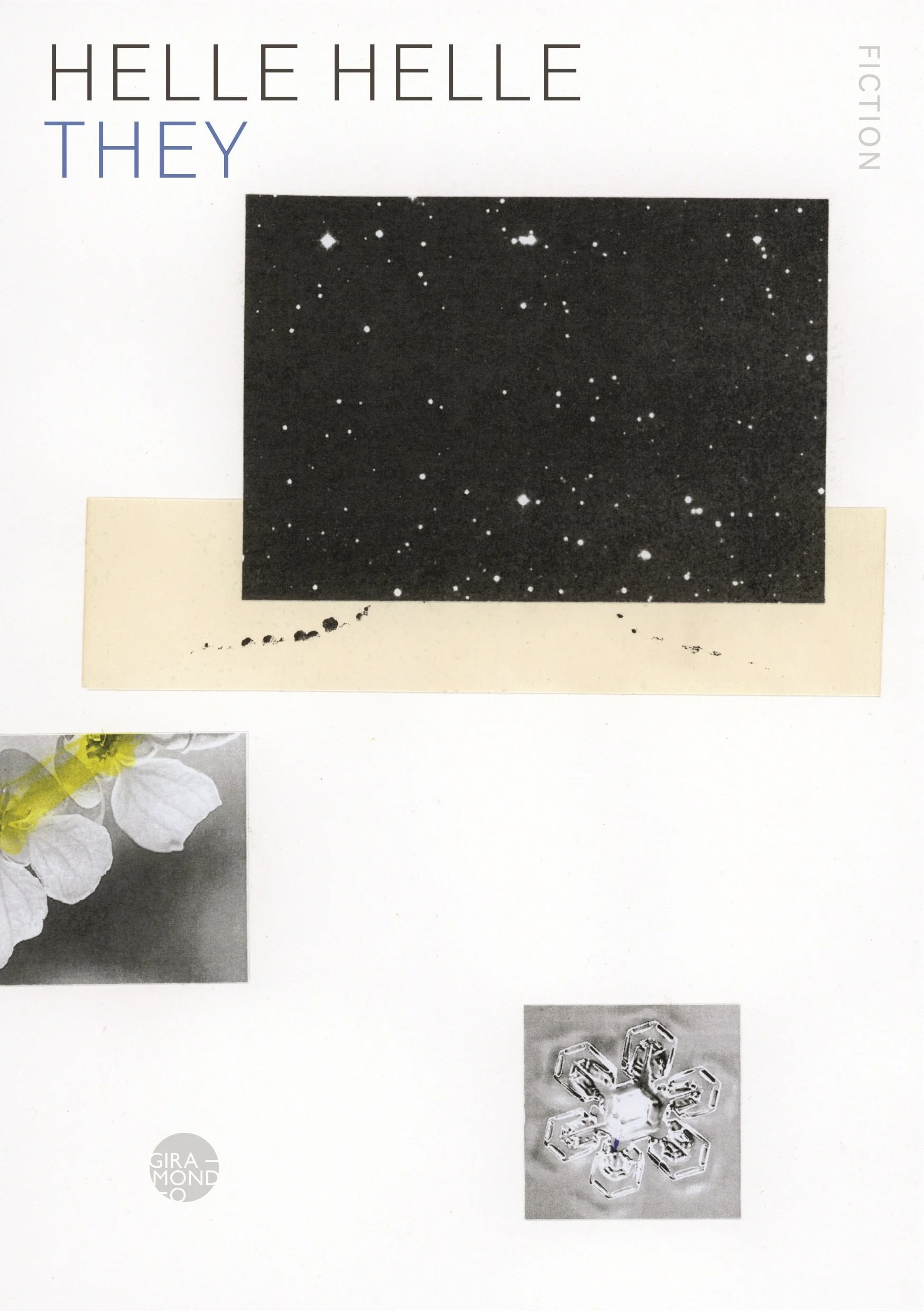

they by Helle Helle (translated from Danish by Martin Aitken) $35

A mother and her sixteen-year-old daughter live in an apartment above a hairdresser's shop in a small island town. Each day is marked by routine and quiet intimacy. They are so enmeshed, so alike in their manners and opinions, it can be hard to tell them apart. Then the mother begins to feel unwell. They carry on with their lives, talk about anything but the diagnosis. The mother goes in and out of hospital, and the daughter, just starting high school, makes new friends but remains essentially alone. Illness, and the possibility of loss, cast a growing shadow over her life. Writing in a multi-layered, perpetual present tense, Helle Helle finds a tender voice for the comedy and awkwardness of her characters' lives, rendered into riveting and affecting English by acclaimed translator Martin Aitken. they is an exquisite portrait of the fragile love between a mother and daughter, and a love letter to 1980s life on the island of Lolland, where the author grew up.

”One of my favorite Danish writers — she's the master.” —Olga Ravn

”Helle Helle's minimalism isn't boring; it crackles with mystery. It's the everyday, and yet it's insistently beautiful.” —Weekendavisen

”Helle Helle's they sharply renders the startling and singular specifics of a life: hairspray, glass trolls, radiators, crocheted curtains, shrimps, baguettes, liver pâté, harem pants, peacoats, denim skirts, the selling of milk, eggs and soap, fried eggs, pineapple, peaches and cheese, garlic, condensed milk, jam, terry-cloth, lemonade, female guitarists, cans of tomato soup, Band-Aids, rustic whole grain bread, cold spaghetti. All this within the binary star gravitational pull of a mother-daughter relationship peering into the void of the mother's sudden, almost certainly terminal, illness. It's a book about class, memory, and the texture of time itself. I'm now a Helle Helle completist.” —Rita Bullwinkel

>>Beautiful minimalism.

>>On reading.

What to Wear by Jenny Bornholdt $25

The poems in What to Wear observe that life means doing ordinary and marvellous things, like going to Bunnings, falling asleep on the train, losing and finding poems, losing and dreaming of our mothers, loving, dying, and deciding what to wear. [Paperback]

”Mischievously joyful, like being in on the very best in-joke. Jenny Bornholdt reveals the strange magic of the everyday. Some of these poems move like a heat-seeking missile set to the heart.’” —Louise Wallace

Leather & Chains: My 1986 diary by Kate Camp $40

Kate Camp turns her poet' s eye on her 1986 diary. Reading The Diary in its entirety for the first time, she revels in 80s touchstones like Revlon Custom Eyes and Ghostbusters on VHS. But amid the daily details, like smoking menthols in Suzy' s Coffee Lounge and wearing Jazzercise tights in a phone box, are moments of drama, even tragedy — being black-out drunk in a spa pool, or watching her father move out of the family home. At the centre of it all is Cameron, his black hair falling over his eyes, intoning in his fake Scottish accent, “Treat me rough, baby.” These entries — over 100 reproduced in full — are a time capsule of a very different era. The Kate Camp of today responds to the blithe accounts of sex, drugs and risk-taking with horror and admiration — and insight. How real are our memories? Can we ever know ourselves? And why is every entry signed off Leather & Chains? [Flexibound]

”Kate Camp reads the words of grownupchild Kate of 1986 — achingly funny, arch and louche, often shocking, always clever. And all of it threaded through with such pain and sadness and unsettling darkness, such yearning to be loved. I thought I knew The Diary so well, after all these years listening and watching from the wings. But reading The Diary myself, as she does in this remarkable project, is richer, funnier and, yes, sadder than experiencing it live in eight-minute snippets. I've often wondered about Kate Camp: how did she get to be so fearless, so peerless, so bold? The answer is in these pages.” —Tracy Farr

Helen of Nowhere by Makenna Goodman $35

In the middle of the countryside, a realtor is showing a disgraced professor around an idyllic house. She speaks not only about the home's many wonderful qualities but about its previous owner, the mystifying Helen, whose presence still seems to suffuse every fixture. Through hearing stories of Helen's chosen way of living, the man begins to see that his story is not actually over — rather, he is being offered a chance to buy his way into the simple life, close to the land, that's always been out of reach to him. But as evening fades into black, he will learn that the asking price may be much higher, and stranger, than anticipated. Philosophically and formally adventurous, at once intimate and cosmic in scope, Helen of Nowhere asks: What must we give up in exchange for true happiness? [Paperback with French flaps]

”Wildly original, unpredictable and funny. Is Helen of Nowhere a ghost story? A satire about back-to-the-land philosophies? A comedy about male obsolescence? Or, conversely, a skewering of identity politics? Perhaps it's just a fable about burn-out or the human hunger for love. It could be all of these.... This is fiction that will sharpen your attention to the world, make it more intense. It reminds us that we don't have to understand or like everything about a book to get something out of it. In fact, allowing ourselves to feel stimulated and perplexed feels like intellectual freedom and an awakening of human potential.” —Johanna Thomas-Corr, The Times

”Virtuosically written, with an insanity inside its sanity — or the other way around — that seems the proper use to make of reality in this moment.” —Rachel Cusk

”Helen of Nowhere is one of the most surprising novels I've ever read. Goodman has found a unique way of blending political urgency and psychological insight with an almost hallucinatory spiritual dimension that manages to strike the reader as perfectly justified, deeply funny and profoundly true.” —Vincenzo Latronico

”Goodman has wrought an epic in miniature, somehow as appealingly vast as a Greek tragedy or a Platonic dialogue, equal parts philosophy and art that's also delightfully wicked, like something from a fairytale or a fever dream.” —Sarah Manguso

>>Continually evolving truths.

>>A house holds a mirror.

>>Love, theory, and the ‘post-cis male moment’.

Coming. Apart. by Edy Poppy (translated from Norwegian by May-Brit Akerholt) $35

The sharp, sensual stories of Coming. Apart. chart the unraveling of relationships in all their complexity. From rural Norway to Berlin, Edy Poppy follows characters caught between intimacy and escape lovers who drift, clash, fracture. A couple's erotic games slip into something darker. A woman retreats to the countryside, shadowed by memory. Another navigates obsession, ambivalence, and solitude with uneasy clarity. Written in a voice that is both visceral and exacting, Edy Poppy's story collection moves along the fault lines of connection and desire. Blurring fiction and lived experience, Poppy offers a fierce meditation on what it means to stay or leave. [Paperback]

"Edy Poppy is a courageous writer who dares to transgress the limits most of us set for ourselves. But she does it so playfully and with such elegance that the reader can't resist coming along to explore forbidden realms. Anatomy. Monotony. has become a cult classic in many circles, and I see no reason why Coming. Apart. should not have the same impact." —Elle

"Fantastic!" —Chris Kraus

“In Coming. Apart. Edy Poppy unflinchingly strips bare the messiness of connection and lust, power imbalances, and the agonizing tension between freedom and constraint—boldly exposing humankind’s darkest desires and traumas, and exploring territory many wouldn’t dare to think, let alone put to paper. It is a mettlesome and provocative collection of short stories that refuses to be ignored.” —Tupelo Quarterly

>>Obsessive surveillance.

>>The next wound.

>>Gaze as a tool.

Edith Holler by Edward Carey $28

Norwich, 1901: Edith Holler spends her days among the eccentric denizens of the Holler Theatre, warned by her domineering father that the playhouse will literally tumble down if she should ever leave. Fascinated by tales of the city she knows only from afar, young Edith decides to write a play of her own about Mawther Meg, a monstrous figure said to have used the blood of countless children to make the local delicacy, Beetle Spread. But when her father suddenly announces his engagement to a peculiar woman named Margaret Unthank, Edith scrambles to protect her father, the theatre, and her play — the one thing that's truly hers — from the newcomer's sinister designs. Teeming with unforgettable characters and illuminated by Carey's trademark illustrations, Edith Holler is a surprisingly modern fable of one young woman's struggle to escape her family's control and craft her own creative destiny. [Paperback]

“An extraordinary achievement: funny, troubling, playful, magical and vastly energetic — sometimes all at once. Edith herself is a fierce, strange creature and entirely unforgettable. Hold on to your hat — and avoid the Beetle Spread.” —A.L. Kennedy

>>The Edith Holler card theatre. >>Yours to download.

>>Millions of words had fallen.

A Long Game: How to write fiction by Elizabeth McCracken $50

'Write every day', 'Show, don't tell', 'Write what you know', 'Kill Your Darlings' — These are some of the most popular nuggets of advice given to writers, generally accepted as true. They are all pieces of writing advice that Elizabeth McCracken expertly and persuasively shoots down in A Long Game. McCracken has been writing for most of her life. Here, she shares insights gleaned along the way, deconstructing received wisdom whilst playfully tackling the mysteries that are inherent to writing and creativity. A book about the life of an artist and a guide to fiction, A Long Game is a revelatory and indispensable resource and will lead all writers, at any stage of their career, back to the page. [Hardback]

”Elizabeth McCracken was my teacher, and it's a joy to know that now more people will have access to her brilliance through A Long Game. A guidebook for any fiction writer, and a problem-solving and cheering companion that makes writing a less lonely business.” —Yiyun Li

”Elizabeth McCracken is that rarest of combinations — a world class writer and a world class writing teacher. With A Long Game she has distilled the electric, inspiring genius, enthusiasm, and wit that she has brought to the classroom for more than three decades and put it into a book that's practically a masters program in itself.” —Paul Harding

”Elizabeth McCracken, one of the greatest, wisest, funniest, and most humane writers you will ever encounter, has written one the greatest, wisest, funniest, and most humane books about writing you will ever read. Have a pen ready. You'll want to underline sentences on every page that make you stop and think or inwardly cheer or nod in recognition. Most importantly, you'll want to run to your desk and write. A Long Game is an absolute gift.” —Cristina Henriquez

>>Rip up all the rules.

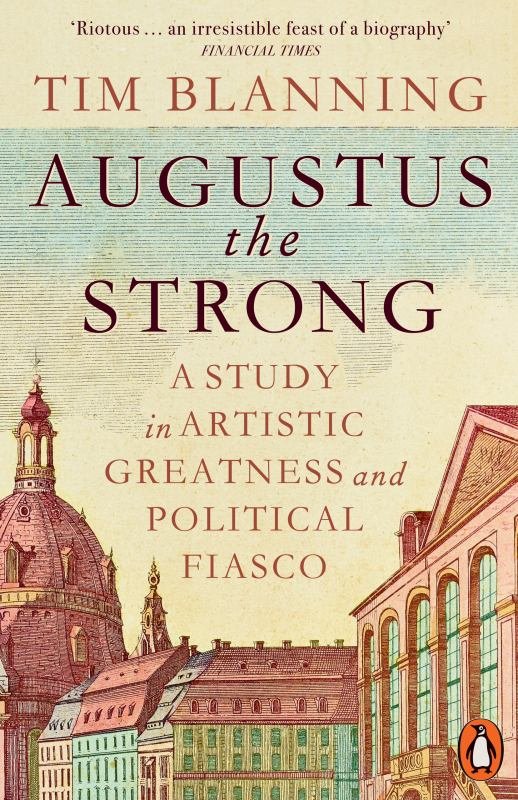

Augustus the Strong: A study in artistic greatness and political fiasco by Time Blanning $36

Augustus is one of the great what-ifs of the 18th century. He could have turned the accident of ruling two major realms into the basis for a powerful European state — a bulwark against the Russians and a block on Prussian expansion. Alas, there was no opportunity Augustus did not waste and no decision he did not get wrong. By the time of his death Poland was fatally damaged and would subsequently disappear as an independent state until the 20th century. Tim Blanning's entertaining and original book is a study in failed statecraft, showing how a ruler can shape history as much by incompetence as brilliance. Augustus's posthumous sobriquet 'The Strong' referred not to any political accomplishment, but to his legendary physical strength and sexual athleticism. Yet he was also one of the creative artists of the age, combining driving energy, exquisite taste and apparently boundless resources to master-mind the creation of peerless Dresden, the baroque jewel of jewels. Augustus the Strong brilliantly evokes this time of opulence and excess, decadence and folly. [Paperback]

”Tim Blanning's riotous biography of an often-forgotten 18th-century king provides historical perspective on the current state of Europe. It is so riotous it is impossible to read without thinking of picaresque characters such as Fielding's Tom Jones and Thackeray's Barry Lyndon. An irresistible feast of a biography of the now oft-forgotten Polish king whom he gloriously brings to life.” —Simon Sebag-Montefiore

”The wonderful story of one of the worst monarchs in European history, told with enormous wit and scholarship by a supremely talented historian. If you have the slightest interest in Germans, Poles, porcelain, jewels, the Enlightenment, military disasters or the pleasures of fox-tossing, then this is the book for you.” —Dominic Sandbrook

Discord by Jeremy Cooper $48

On a night in August, an audience at the Royal Albert Hall attends the first ever concert of ‘Distant Voices’. The Proms performance is the culmination of a year's work between the middle-aged composer Rebekah Rosen and the young star-saxophonist Evie Bennet. Alternating between both perspectives, Discord charts the course of their intense and at times fractious relationship, the resonances and dissonances both women find within one another, as well as the struggles and satisfactions that accompany an artistic life. At the heart of the novel is an inquiry into the generative force behind creative collaboration. In what ways does the inexpressible — that amorphous space of friction and unity between musicians — become indelible? And by what process do flawed individuals create works of transcendence? [Paperback with French flaps]

”It's very hard indeed to write fiction about music but Jeremy Cooper does so with triumphant aplomb. Discord is a tremendous, quietly enthralling achievement.” —William Boyd

”Jeremy Cooper's Discord is as nakedly truthful a novel as you could ever hope to read. Its characters are completely and utterly convincing and their interactions with one another are filled with all of the loveliness and foolishness and tenderness of real life.” —Aidan Cottrell-Boyce

”Quietly, irresistibly compelling. Jeremy Cooper's interior worlds fill you up, become the air around you, conduct the sounds of every day — while you are reading, and while the book waits for you to pick it up again. Discord is an enthralling human melody.” —Ben Pester

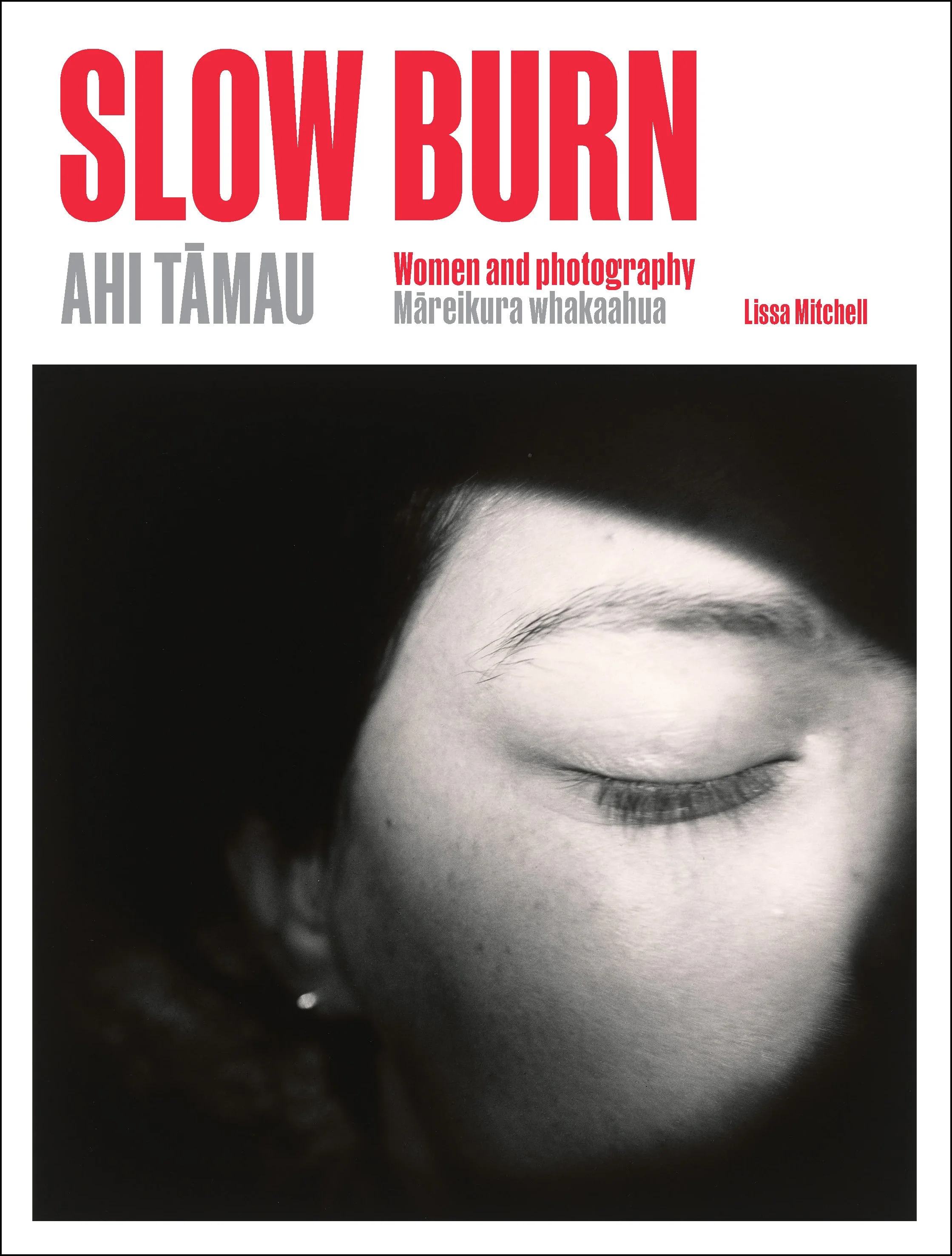

Slow Burn / Ahi Tāmau: Women and Photography / Mareikura Whakaahua by Lissa Mitchell $35

"Researching, collecting and writing about photography, I have often wondered where the women were." Lissa Mitchell. Slow Burn Ahi Tāmau showcases the diverse range of photography by women and non-binary artists from Aotearoa New Zealand, spanning the 1960s to today. Published to accompany a major survey exhibition from Te Papa's collections and to spark a conversation between past and present, this fully illustrated book explores themes of identity, whānau, place, and time through a feminist lens. Highlighting over 150 works by 50 artists, Slow Burn illustrates how ways of seeing can be passed down, reimagined, and slowly reignited. Featured artists include Anne Noble, Fiona Pardington, Natalie Robertson and Lisa Reihana. The curator's essay provides further historical context to the exhibition, and biographies of the photographers make this a valuable research resource. Slow Burn builds on ten years of deeply considered research, inclusive collection decisions, and the 2023 publication of Lissa's acclaimed book Through Shaded Glass: Women and photography in Aotearoa New Zealand 1860-1960. The exhibition and this book bring work by photographers from the last 65 years out of the storeroom and into conversation with each other — a celebration of photography's ever-evolving nature in Aotearoa. [Paperback]

>>Look inside.

>>Through Shaded Glass.

Read our latest newsletter

5 February 2026

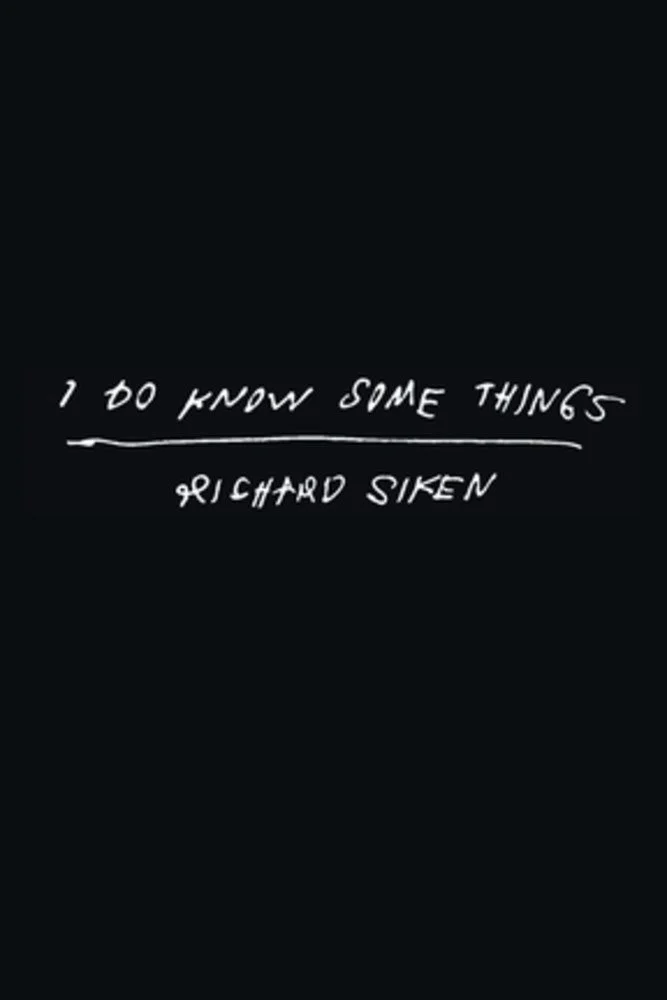

Following a stroke that was initially mistaken for a panic attack, the poet Richard Siken found himself having to completely rebuild his relationship with his body, with his world, and with language itself — the medium that previously had come most naturally to him. This wonderful, darkly hilarious book, both vitriolic and tender, began as a series of exploratory and explanatory survival notes to himself and built into a series of playful interrogations of memories, traumas and losses, a pinning of personal phantoms, a renegotiation of the contract between inner and outer worlds, and an unfurling of new and vulnerable possibilities in language and in life. Recommended.

"An astonishing feat of poetic prowess. Siken has created 'an encyclopedia of myself,' a kaleidoscope of memory, language and identity that reveals — at times revels — in the faultiness of our own narratives. Siken's voice — and language — is both rooted and aloft, even as he avers that these are not 'poems of song.' Beyond such marvels, this is a virtuosity of candor and technique, bound by a seemingly effortless linguistic choreography that leans into multiplicity and mutability, with continuous sparks and joys, from one of our finest contemporary poets." —Mandana Chaffa, Chicago Review of Books

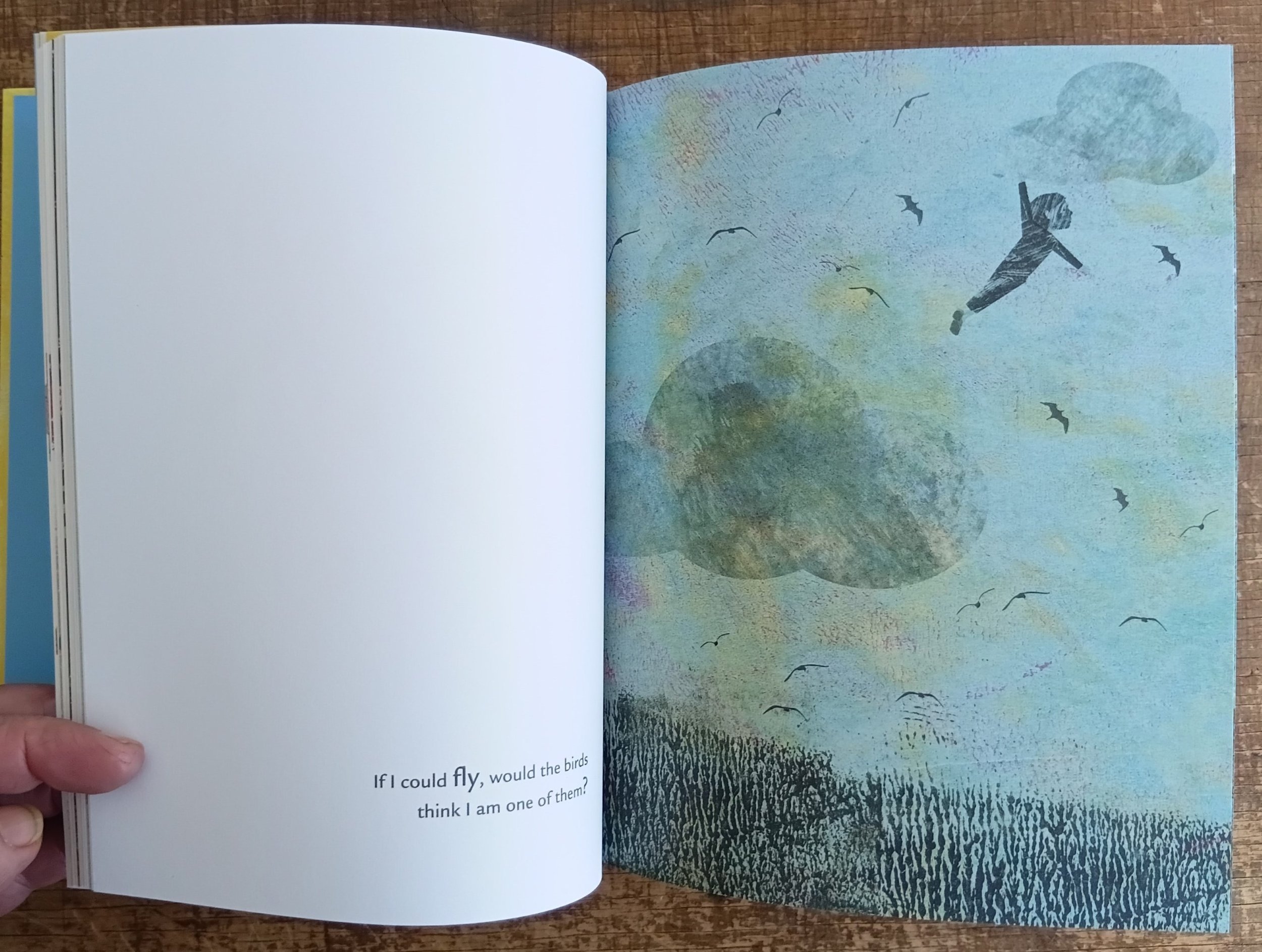

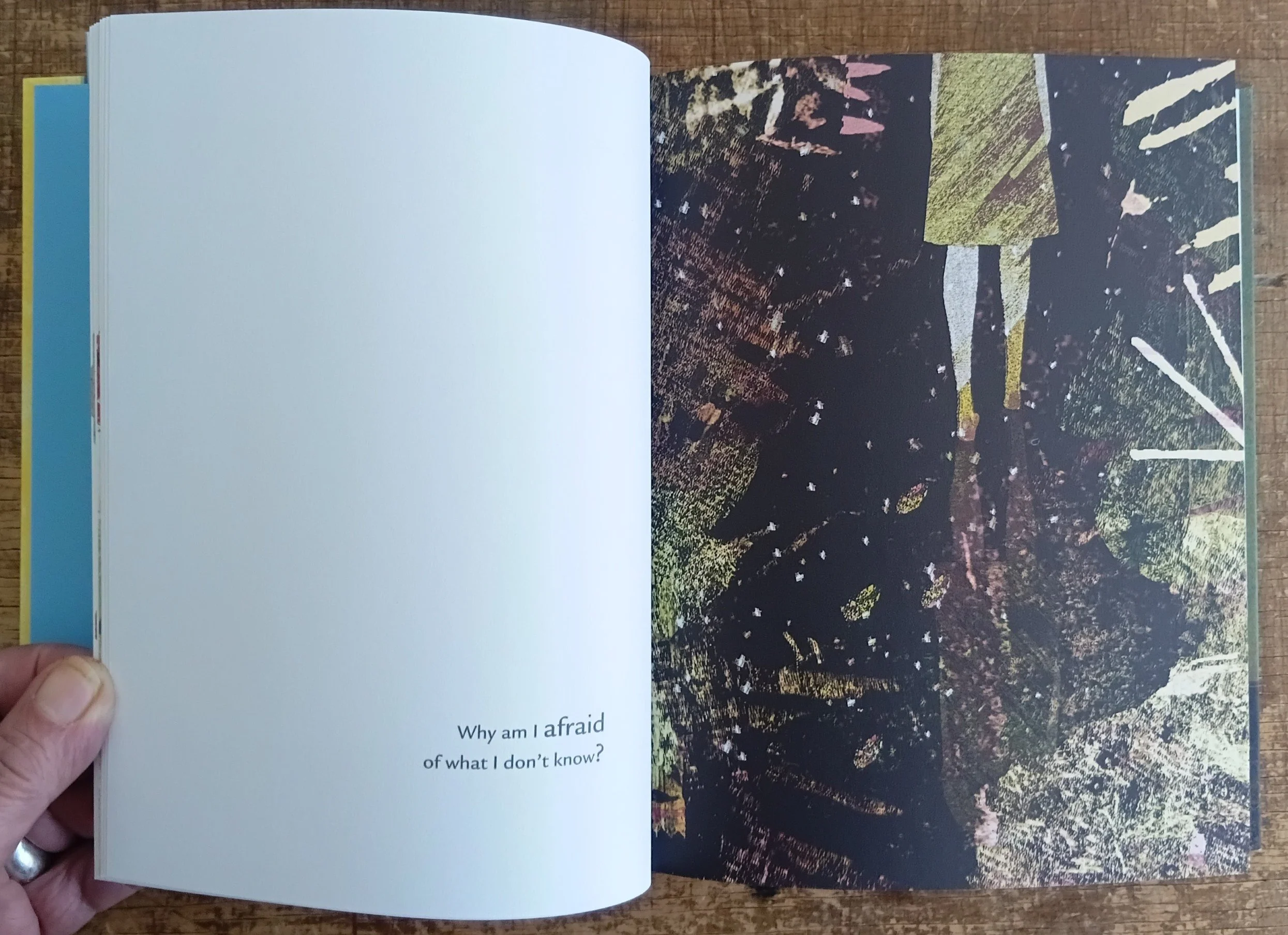

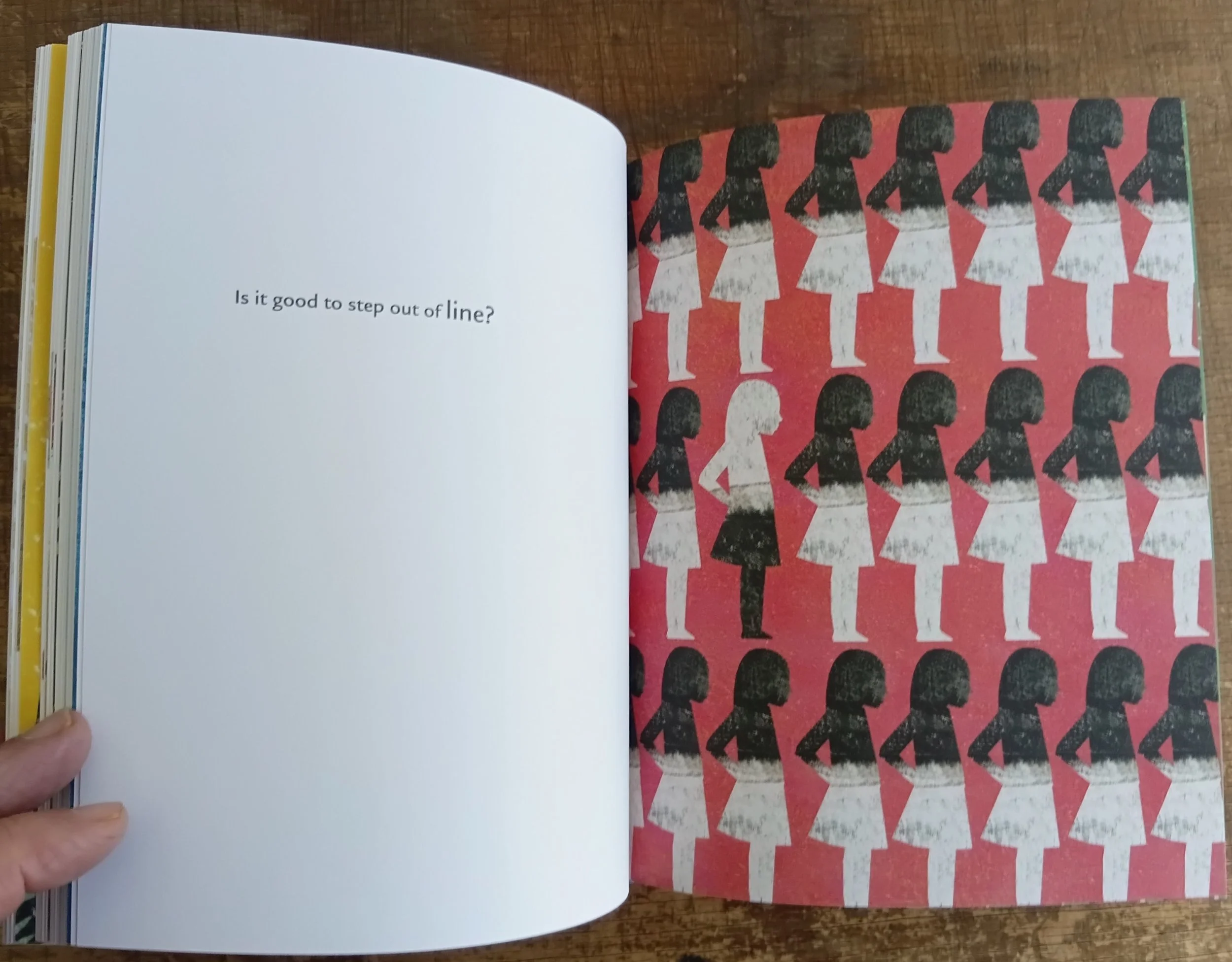

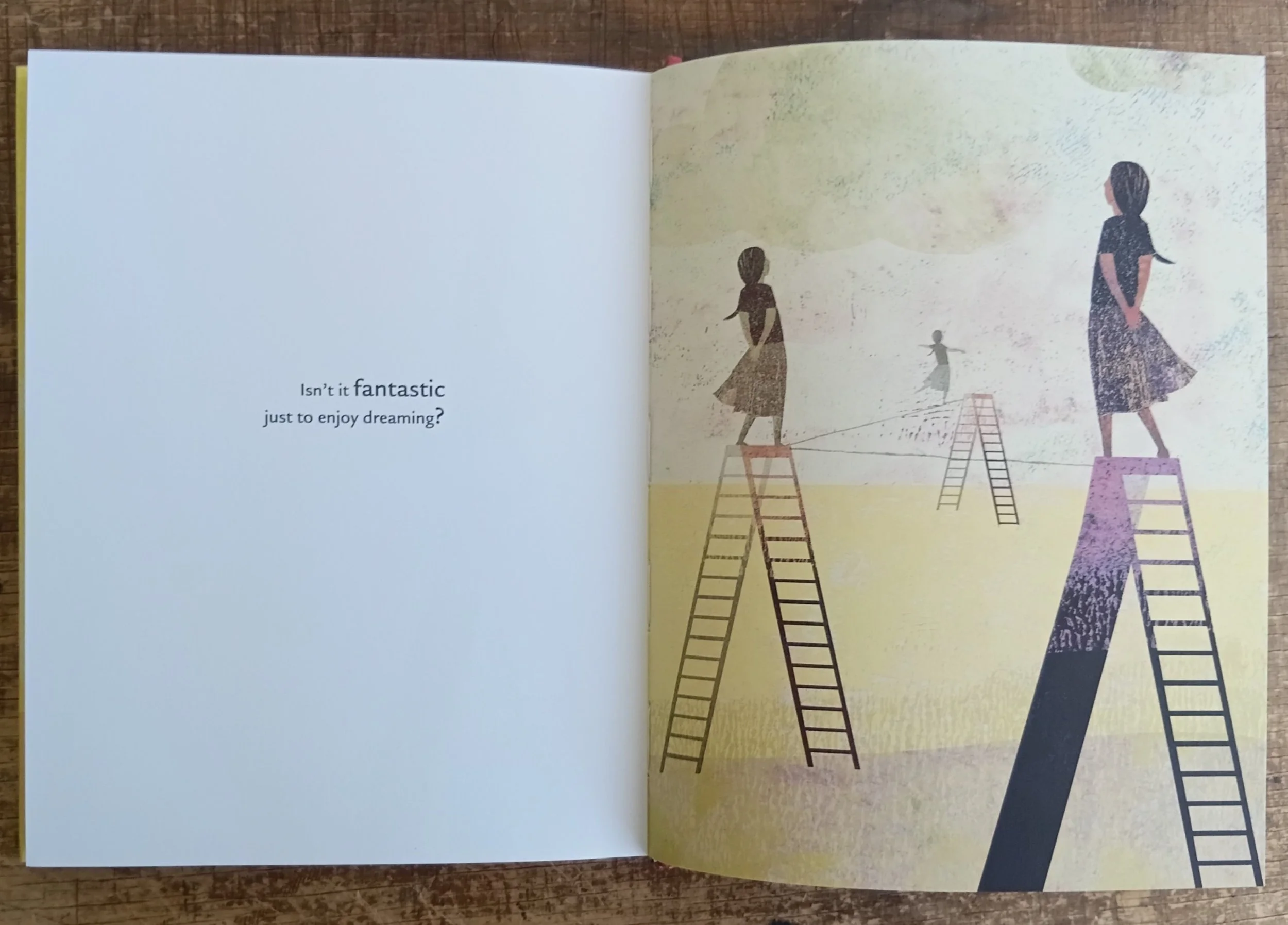

Britta Teckentrup is a German illustrator and author with over 70 children’s books to her name. Published in over 20 countries, she illustrates her own as well as other authors’ picture books. Many of her books quickly become favourites, and they range from board books to sophisticated picture books. What they all have in common is a desire to instill a feeling of wonder and curiosity. My favourite of her books is My Little Book of Big Questions. This is packed with ideas, beautifully illustrated, and filled with questions, both familiar and surprising. At 190 pages this is a substantial small hardback. The questions suit any age — from youngsters to adults. The ideas within these pages can be set free to roam in the imagination or used as conversation starters or prompts for writing or other creative responses. The questions range from the whimsical and tentative to the philosophical and provocative. Some questions may have answers and every reader will respond in their own way; other questions lead to more questions, opening doors to stories and journeys; while others will illicit a response of ‘who knows?’ Some questions trigger emotions, while other may send you on a fact-finding mission.

Here’s a small selection:

Will I be able to fly someday?

Who will be my friend?

Why I am afraid of what I don’t know?

Am I special?

Why is nature so colourful?

Are dreams as true as reality?

The illustrations, eye-catching and attractive, are variously thoughtful, joyful and enigmatic. Teckentrup uses colour, texture, silhouettes, and line to capture mood and emotion. There is joy in the light sky of a cartwheeling child. There is the brilliant blue of a dive into a pool of water. Rich textures adorn a field where a quest to find something hidden is under way. The bright yellow light of the future in seen through a window frame as a child looks from the familiar to the promise of what is to come. There is simpliicity of line and colour for quiet thoughts, and bold colours and energetic forms for questions that spur us to action.

This is a delightful book, one that I never tire of opening. It is brimming with ideas, both big and small, about feelings, human interactions, the meaning and the mysteries of life, and how all these things spark our imagination and keep us curious.

Emil Cioran is the philosopher of personal and collective frailty and failure, of emptiness, of hopelessness, of the eschewing of all answers (“Having resisted the temptation to conclude, I have overcome the mind.”). He rails against society, against both choice and necessity, against all values. I thought I would like him more than I do. Perhaps it is that he trumpets his nihilism, that he shouts out the immanence of our demise from the event horizon of whatever black hole we are heading towards, that his pessimism is, above all, dramatic (does this call its authenticity into question? (I don’t think so)), that makes me tire of him (he should perhaps be read (by me, at least) in small doses). Our differences are perhaps more of temperament than of territory; to me the underlying nullity of existence is more irredeemable than tragic, and I am to a degree suspicious of the heroic trappings and lyricism of his despair. That said, Cioran is an important, interesting (and frequently amusing) thinker, an heir to Nietzsche, and there is much to admire (and be amused by) in his books. His words dissolve civilisation as acetone dissolves paint (that’s got to be a good thing). The contents page of this book reads like the publishing list of an American academic publisher (“Genealogy of Fanaticism – In the Graveyard of Definitions – Civilisation and Frivolity – Supremacy of the Adjective – Apotheosis of the Vague – The Reactionary Angels – Militant Mourning – Farewell to Philosophy – Obsession of the Essential” &c, &c), and the book itself contains enough nihilistic aphorisms to fill a lifetime’s worth of anti-inspirational calendars (now, there’s a publishing project…), for example (although this is typically insensitive to anyone with literal leprosy): “One is ‘civilised’ insofar as one does not proclaim one’s leprosy.” Great stuff.

The Treaty of Waitangi | Te Tiriti o Waitangi: An iIlustrated history by Claudia Orange $50

Claudia Orange's writing on the Treaty of Waitangi has played a central role in national understanding of this foundational document. This third edition of her standard work is the most comprehensive account yet, presented in full colour and drawing on Dr Orange’s recent research into the nine sheets of the Treaty and their signatories.

50 Years of The Waitangi Tribunal edited by Carwyn Jones and Maria Bargh $65

The collection highlights the breadth of issues considered by the Tribunal and also the impact the Tribunal has had on complex legal concepts, representation of communities, and understanding of te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Understanding Te Tiriti: A handbook of basic facts about te Tiriti o Waitangi by Roimata Smail $25

Distills essential information clearly and concisely.

Undersranding Hauroa: A Handbook of basic facts about te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Health System by Roimata Smail $25

A short, accessible guide explains what hauora really means — not just healthcare, but the wellbeing of body, mind, spirit, and whānau, grounded in the whenua — and how Te Tiriti o Waitangi guaranteed Māori authority over it.

The Treaty of Waitangi — Te Tiriti o Waitangi by Ross Calman $30

A non-fiction resource for general readers and schools, introducing complex subjects in concise terms. Illustrated with explanatory graphics, fact boxes, and photos.

Becoming Tangata Tiriti: Working with Māori, Honouring the Treaty by Avril Bell $30

Becoming Tangata Tiriti brings together twelve non-Māori voices — dedicated professionals, activists and everyday individuals — who have engaged with te ao Māori and have attempted to bring te Tiriti to life in their work.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi / The Treaty of Waitangi by Toby Morris, Ross Calman, Mark Derby, and Piripi Walker $25

Full-colour graphic novel about Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi. This reorua (bilingual) graphic-novel-style flip book presents important information in a visually appealing and engaging way.

Te Waka Hourua Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika! $30

Te Waka Hourua is a tangata whenua-led, direct action, climate and social justice rōpū.

The State of Māori Rights by Margaret Mutu $55

Mutu documents the state of Māori rights over a thirty-year period and speaks to the determination of Māori as indigenous people.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi Relationships: People, Politics and Law edited by Metiria Stanton Turei, Nicola R Wheen, and Janine Hayward $50

This group of essays takes a dynamic approach to understanding Tiriti relationships, acknowledging the ever-evolving interplay between the Crown and Māori through time.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, 1840 introduced by Claudia Orange $40

The nine sheets of the Treaty are shown, with a vivid account of their signing. Names, iwi and hapu are given for the Treaty signatories, along with information about their lives.

He Whakaputanga, 1835 introduced by Vincent O’Malley $40

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni/The Declaration of Independence of New Zealand was signed by fifty-two rangatira from 1835 to 1839. It was a powerful assertion of mana and rangatiratanga.

The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi by Ned Fletcher $70

How was the English text of the Treaty of Waitangi understood by the British in 1840? That is the question addressed by historian and lawyer Ned Fletcher, in this authoritative work.

Tangata Whenua: An illustrated history by Atholl Anderson, Judith Binney, and Aroha Harris $100

This remarkable book charts the sweep of Māori history from ancient origins through to the twenty-first century. Through narrative and images, it offers a striking overview of the past, grounded in specific localities and histories. This should be on everyone’s bookcase.

>>Also available as a unillustrated paperback.

Tears of Rangi: Experiments Across Worlds by Anne Salmond $50

A study of New Zealand as a site of cosmo-diversity, a place where multiple worlds engage and collide. Beginning with a fine-grained inquiry into the early period of encounters between Māori and Europeans in New Zealand (1769-1840), Salmond then investigates such clashes and exchanges in key areas of contemporary life - waterways, land, the sea and people.

Introducing He Whakaputanga by Vincent O’Malley and Jared Davidson $20

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni/The Declaration of Independence of New Zealand was signed by fifty-two rangatira from 1835 to 1839.

Introducing Te Tiriti o Waitangi by Claudia Orange and Jared Davidson $20

In 1840, over 500 Māori leaders put their names to a significant new document: Te Tiriti o Waitangi or the Treaty of Waitangi. Through their signatures, moko or marks they were making an agreement with the British Crown.

Ka Whawhai Tonu Mātou: Struggle without End by Ranganui Walker $45

Since the mid-nineteenth century, Māori have been involved in an endless struggle for justice, equality and self-determination. In this book Dr Walker provides a uniquely Māori view, not only of the events of the past two centuries but beyond to the very origins of Māori people.

Knowledge Is a Blessing on Your Mind: Selected Writings, 1980–2020 by Anne Salmond $65

This book traces Anne Salmond's journey as an anthropologist, as a writer and activist, as a Pakeha New Zealander, bringing together her key writing on the Maori world, cultural contact, Te Tiriti and the wider Pacific.

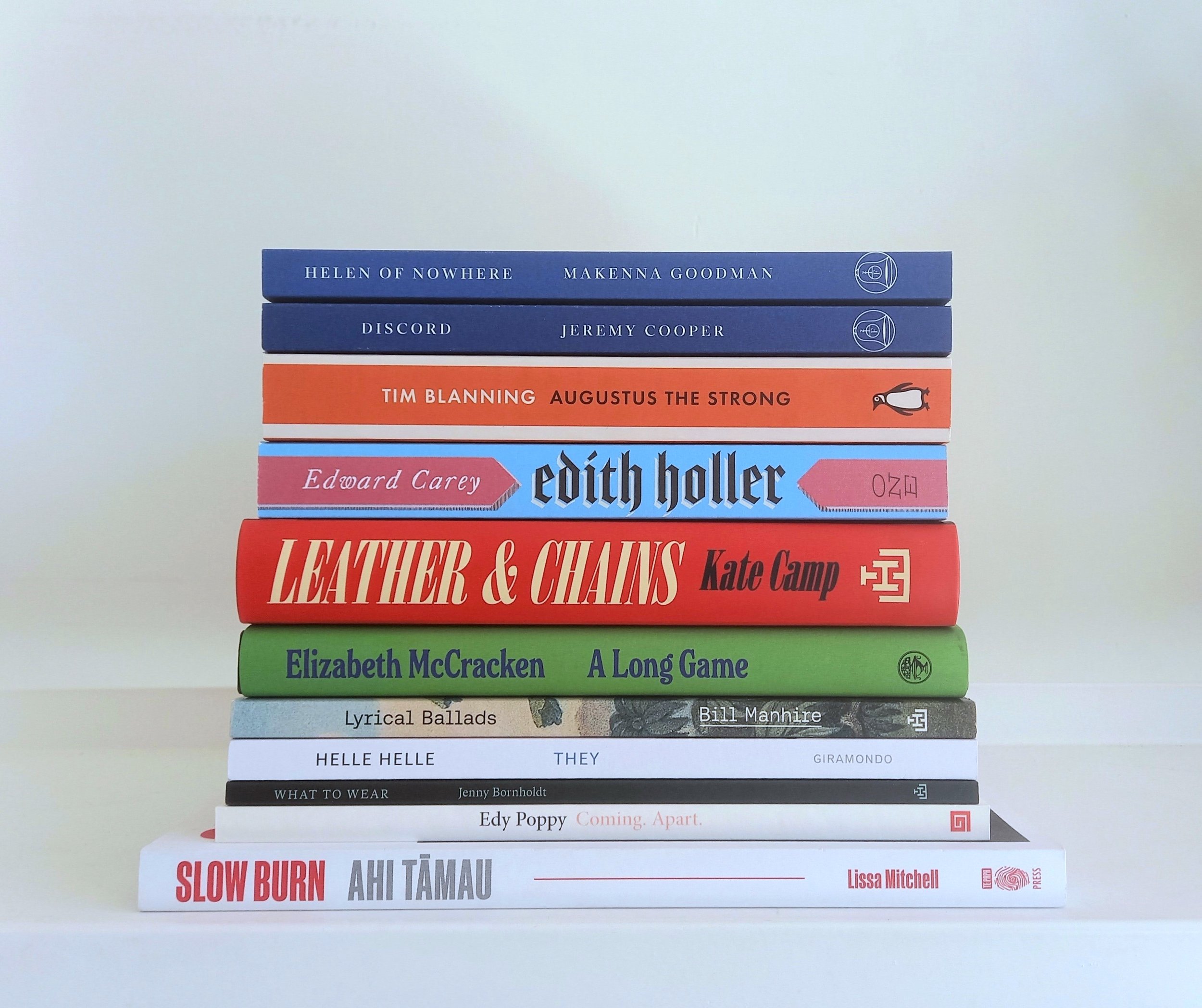

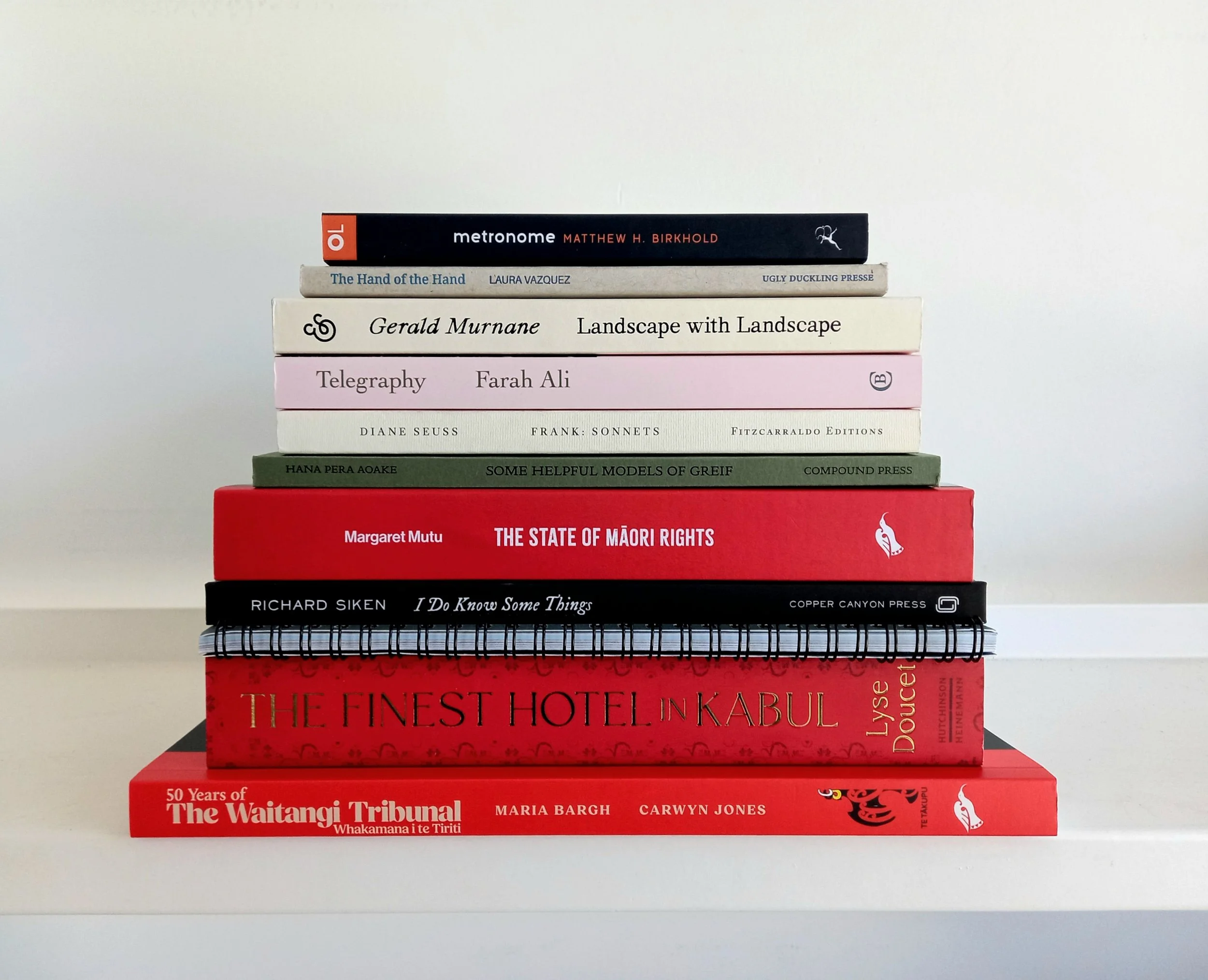

A selection of similarly sized books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

All your choices are good! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

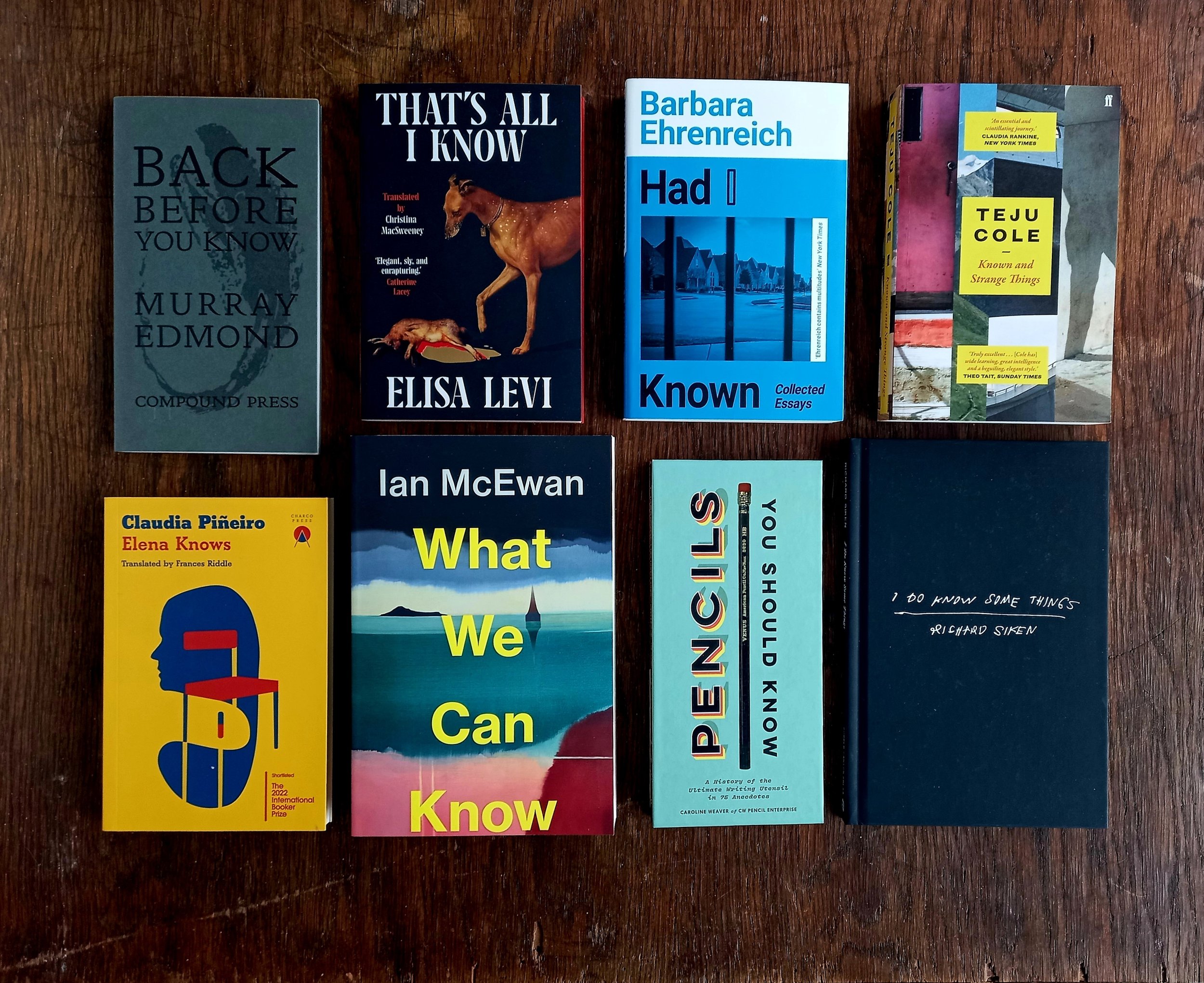

I Do Know Some Things by Richard Siken $50

Richard Siken's long-anticipated third collection, I Do Know Some Things, navigates the ruptured landmarks of family trauma: a mother abandons her son, a husband chooses death over his wife. While excavating these losses, personal history unfolds. We witness Siken experience the death of a boyfriend and a stroke that is neglectfully misdiagnosed as a panic attack. Here, we grapple with a body forgetting itself — "the mind that / didn't work, the leg that wouldn't move...". Meditations on language are woven throughout the collection. Nouns won't connect and Siken must speak around a meaning: "dark-struck, slumber-felt, sleep-clogged." To say "black tree" when one means "night." Siken asks us to consider what a body can and cannot relearn. "Part insight, part anecdote," he is meticulous and fearless in his explorations of the stories that build a self. Told in 77 prose poems, I Do Know Some Things teaches us about transformation. We learn to shoulder the dark, to find beauty in "The field [that] had been swept clean of habit." Recommended. [Hardback]

"An astonishing feat of poetic prowess. Siken has created 'an encyclopedia of myself,' a kaleidoscope of memory, language and identity that reveals — at times revels — in the faultiness of our own narratives. Siken's voice — and language — is both rooted and aloft, even as he avers that these are not 'poems of song.' Beyond such marvels, this is a virtuosity of candor and technique, bound by a seemingly effortless linguistic choreography that leans into multiplicity and mutability, with continuous sparks and joys, from one of our finest contemporary poets." —Mandana Chaffa, Chicago Review of Books

"The second-person strategies of Crush are abandoned in I Do Know Some Things for a more direct style, but Siken's signature intensity still throbs between sentences. Siken's prose is often deft and exciting. As he relearned everything, the prose poem helped him rediscover how to create poetic tension, how to be dynamic without the gravity-defying magic of enjambment. Syntactic variation. Quick, unexpected shifts in register. Artful repetition. These are all refined strategies in the collection. The prose is also a steadying element. It is another way of not losing oneself, of not falling through the cracks." —Richie Hoffman, Yale Review

>>Wiped clean.

>>The most fundamental poetic device.

>>Landmarks for meaning.

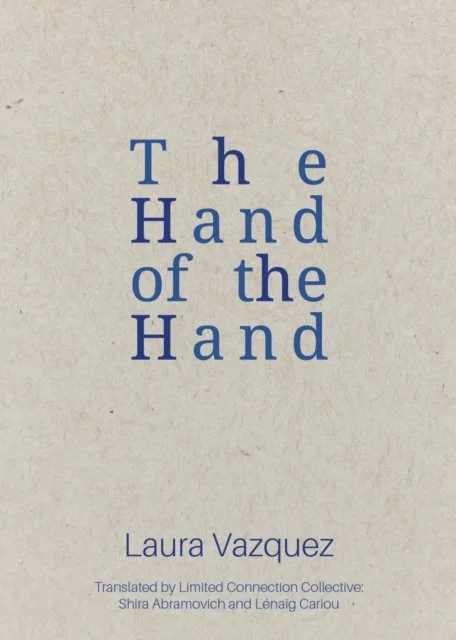

The Hand of the Hand by Laura Vazquez (translated from French by Shira Abramovich and Lénaïg Cariou) $48

The Hand of the Hand brings us poetry from a visceral alternate world in which earth, animal, and human intertwine — where stomachs have meadows, milk pours itself over trees, and flies wash the dead. Vazquez pulls deceptively simple, bare language into puzzling formations, creating an ambient unease. By turns lyrical and absurd, The Hand of the Hand explores the mystery and strangeness of what it means to be both speech and body, tongue and dirt. English/French bilingual edition. [Paperback]

”The tentacular porousness of Laura Vazquez’s début collection sweeps selfhood off its feet.” —Sarah Riggs

”This remarkable and subtle poetic series moves continually outward—one thing leads to another and another, gaining momentum until its evocations achieve a true fusion of body and world. Whether through forests, ants, stones, or words, it’s a fusion that allows the reader, too, to become one with the world as a unified gesture, and it’s the hand—as bridge, as touch, as grasp—that animates this gesture, this hand that seems ubiquitous, which, in fact, it is. “ —Cole Swensen

”In this knockout first collection in English, Laura Vazquez shows us the simplicity and the complexity of the real. But what is the real? It’s these poems, written right on the very skin of it, where the human and everything else feel it. These poems, like Lucretius’, explain the world to us at the granular, allowing us to see these strange perceptions and arrangements of body (‘I folded my tongue, the way I know how’) in all its pleasure and wonder.” —Eleni Sikelianos

>>Read some extracts.

>>The Endless Week.

Some Helpful Models of Grief by Hana Pera Aoake $30

A composite chronicle of various loves — desired, lost, or never realised — and their corresponding joys and griefs against the backdrops of contemporary art and late capitalism. These poems radiate with Aoake's characteristic force, tenderness, intelligence, and humour, often all within the very same breath. The personal is the political is the personal. [Paperback]

”Everything Hana writes has a pulse. It could be moss, Britney or Plato but it sings a song that is nervous, in the body and out of the body. You’d be a fool not to take in all of Hana’s grins.” —Talia Marshall

”Hana’s writing is daring, elliptical, charismatic and above all, interesting. The kind of writer where it doesn’t matter what the subject is, you know you are always in good company.” —Hera Lindsay Bird

“He haerenga whakatautau, he haerenga atamai, he haerenga ngoto. Sometimes difficile, always différente, Some helpful models of grief is an unique, polymorphous panorama of pāmamae that will be sure to beguile any reader.” —Vaughan Rapatahana

”Hana has always had a way of using words to weave together complex stories and narratives. The words and pieces found throughout this collection are tender and beautiful.” —Khadro Mohamed

>>Read some extracts!

>>Look inside.

>>A bathful of kawakawa and hot water.

Telegraphy by Farah Ali $38

Growing up in Pakistan, Annie experiences the death of her mother, goes to college in Karachi, falls in love with a singer in a band, marries the wrong man, and all her life has visions and illnesses no doctor can explain. Signals are received by the body from across time and space. Passages interwoven with Annie’s narrative include Vesalius stealing the corpse of a hanged man, a visit to the house of the 17th-century Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch, correspondence between far-flung friends in the 19th-century Ottoman Empire, a family’s centuries-long dispersal following an earthquake in Kibyra in 23 CE, and a man stepping onto a landmine in contemporary Waziristan. [Paperback with French flaps]

‘“Farah Ali’s novel, Telegraphy, connects the past with the present, the mythical with the ‘real’. It connects our desires, our longing, the fear that haunts even waking hours, with what we end up becoming — pieces of a whole that was fractured from the beginning, the skin around the bones just a fragile casing for the unbearable weight of suffering. Well crafted, deeply pensive, this is a novel that speaks to each one of us, if we dare to speak to ourselves.” —Feryal Ali Gauhar

”Telegraphy is a deeply strange book. The ethereal quality of Farah Ali’s writing holds this curious, clever, almost devious book with such tenderness, I felt I was in the hands of a writer who had been working for decades to distil this fine work.” —Lara Pawson

”A true book of the body, its pains and resonances, and a bold, unique structure with a captivating voice.” —Han Smith

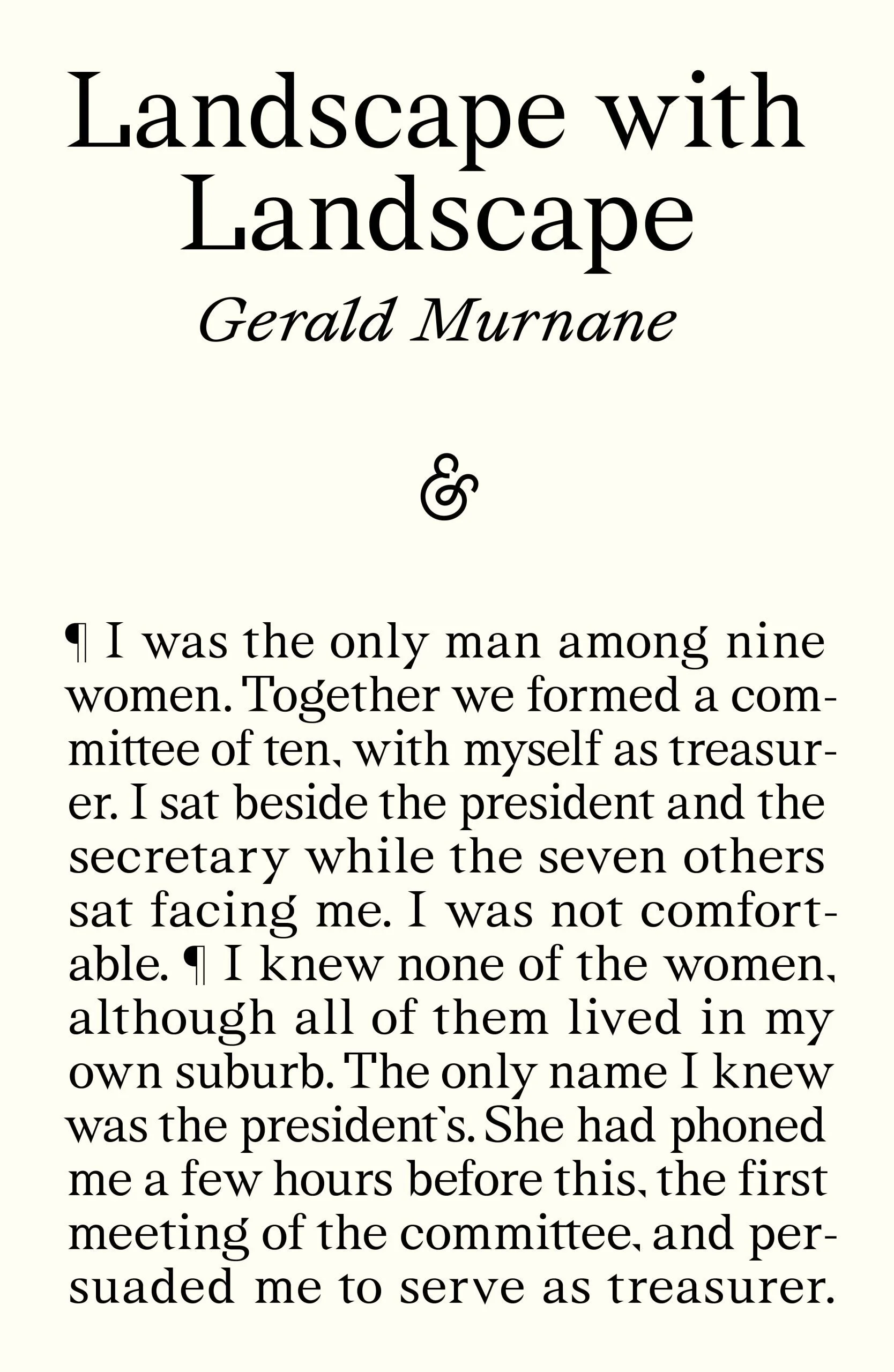

Landscape with Landscape by Gerald Murnane $48

Landscape with Landscape was Gerald Murnane's fourth book, after The Plains, and his first collection of short fiction. When it was first published, thirty years ago, it was cruelly reviewed. "I feel sorry for my fourth-eldest, which of all my book-children was the most brutally treated in its early years," Murnane writes in his foreword to this new edition. In hindsight it can be seen to contain some of his best writing, and to offer a wide-ranging exploration of the different landscapes which make up the imagination of this extraordinary Australian writer. Five of the six loosely connected stories also trace a journey through the suburbs of Melbourne in the 1960s, as the writer negotiates the conflicting demands of Catholicism and sex, self-consciousness and intimacy, alcohol and literature. The sixth story, 'The Battle of Acosta Nu', is remarkable for its depth of emotion, as it imagines a Paraguayan man imagining a country called Australia, while his son sickens and dies before his eyes. [Paperback with French flaps]

”Murnane is unlike anyone else, the sort of writer who demands to be read in a new way but, above all, demands to be read.” —Brian Evenson, Chicago Review of Books

”The emotional conviction is so intense, the sombre lyricism so moving, the intelligence behind the chiselled sentences so undeniable, that we suspend all disbelief.” —J. M. Coetzee

”This is some of his finest writing, and a major work by any measure.” —Michael LaPointe, Times Literary Supplement

>>Read Thomas’s reviews of some others of Murnane’s fictions.

frank: sonnets by Diane Seuss $35

”The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without,” Diane Seuss writes in this brilliant, candid work, her most personal collection to date. These poems tell the story of a life at risk of spilling over the edge of the page, from Seuss's working-class childhood in rural Michigan to the dangerous allures of New York City and back again. With sheer virtuosity, Seuss moves nimbly across thought and time, poetry and punk, AIDS and addiction, Christ and motherhood, showing us what we can do, what we can do without, and what we offer to one another when we have nothing left to spare. Like a series of cells on a filmstrip, frank: sonnets captures the magnitude of a life lived honestly, a restless search for some kind of 'beauty or relief'. Seuss is at the height of her powers, devastatingly astute, austere, and — in a word — frank. [Paperback with French flaps]

”This book is a response to death, a way of living in knowledge of death's privations. What Seuss is hoping for is an extended enough death to allow for a witty recognition of the shape it is imposing on the life it ends. Beyond that, though, what she wants is enough life to make her death into a kind of 'last rhyme', a sound that radiates both into the past and into the future, where it might make contact with your body, or mine.” —Kamran Javadizadeh, London Review of Books

”Seuss layers the work with a litany of cultural and literary references. It is at that bright, fascinating collision between tradition and innovation that these poems reside.” —Soft Punk Magazine

”These poems are taut and careful glimpses into a life lived on the fringes but threaded with wildness; there is a constant sense that everything they contain might erupt at any moment. If autobiographical writing is an attempt to fix a life inside language, frank: sonnets and Modern Poetry are both convincing arguments for the absolute impossibility of ever really succeeding in doing so. Instead, they offer an alternative: debris, glimpses, constellations, ghosts. Suffering and all its attendant bewilderment is given the space it deserves, and pleasure, transcendence, and love are all given due space alongside it.” —Maija Makela, Stinging Fly

>>What is a coffin for?

>>Body parts will always wash up.

A Parliament of Fog by Layne Waerea $35

For more than a decade, fog has rematerialised throughout the work of lawyer-turned-artist Layne Waerea. Her public interventions and performances explore what she describes as “legal-social subjectivities”, centering the implications of Te Tiriti o Waitangi as Aotearoa New Zealand’s only living treaty with Māori. For Waerea, the act of chasing fog pursues a physical or ideological space where borders can be tested — “a fertile area where there are lots of question marks” — and where imagination, hope, participation, and failure can be explored. A Parliament of Fog celebrates ten years of Waerea’s ongoing project the chasing fog club (Est. 2014), and also marks the occasion of its second-ever “Annual General Meeting.” Developed over 2023-24 within a fraught political climate leading up to the New Zealand elections and the first term of a new right-wing coalition government, the publication approaches the club — and Waerea’s recent practice — as a springboard for taking the pulse of the moment. Reflecting on the recent activities of the club in dialogue with a group of collaborators, A Parliament of Fog considers how conditions of opacity, uncertainty, and transition might offer space for collective reimagining. Featuring contributions by the chasing fog club (Est 2014), Sophie Davis, Ioana Gordon-Smith, Deborah Rundle, and Layne Waerea. [Paperback (appropriately spiral-bound)]

>>Look inside.

50 Years of the Waitangi Tribunal: Whakamana i te Tiriti edited by Maria Bargh and Carwen Jones $50

The Waitangi Tribunal has been a unique and integral part of the Aotearoa New Zealand judicial and legislative process, upholding te Tiriti o Waitangi and providing expertise on historical claims, Maori language, land, resources and contemporary issues. This collection contains chapters on themes of land, water and the natural environment, the settlements process, the Kaupapa Inquiries, and issues of social policy, mana, and rangatiratanga, each written by an expert in the area. There are also interviews with two past chairpersons of the Tribunal. The collection highlights the breadth of issues considered by the Tribunal and also the impact the Tribunal has had on complex legal concepts, representation of communities, and understanding of te Tiriti o Waitangi. [Paperback]

The State of Māori Rights by Margaret Mutu $55

The State of Māori Rights was first published in 2011 and brought together a Māori view of events and issues that occurred between 1994 and 2009 with a direct impact on Māori. This includes the 1994 fiscal envelope policy debate, the 50,000-strong protest march against the foreshore and seabed legislation, the Waitangi Tribunal and its Treaty claims process, and media attacks on Māori MPs. This new edition, revised and updated with new chapters, brings Margaret Mutu’s The State of Māori Rights through to 2024, a time when Māori rights under the Treaty of Waitangi are once again being violated. Mutu covers Māori responses to COVID-19 and to national disasters such as the White Island eruption and the Christchurch Mosque Attacks on the Muslim community. Māori initiatives and success stories run through these years too, which, in Mutu’s words, “encourage us not to lose sight of our ancestors’ vision”. [Paperback with French flaps]

Metronome by Matthew H. Birkhold $23

When the metronome was invented in 1815, it transformed the music world. Composers and musicians now had a tool that could help them maintain a precise and consistent tempo. And while giants of classical music like Beethoven early embraced the metronome and proponents came to see its essential role in music instruction, critics believed it created mindless players and inhibited the creation of great art. The metronome evokes strong feelings because of its uncompromising power. Through it, we are connected to the past, propelled into the future, and kept focused on the present. For that reason, this object has appeared in unlikely settings as athletes, scientists, psychologists, authors, and other professionals have found uses for it beyond music. Metronome uncovers the surprising and fraught history of a timeless object. [Paperback with French flaps]

”In this clever and thoughtful exploration, Matthew Birkhold reveals how a simple ticking device became both liberator and tyrant, reshaping not just how we make music but how we understand rhythm, precision, and ultimately, our own humanity.” —Christopher Cerrone

”Matthew Birkhold reveals the fascinating history of the metronome that not only covers music, but touches upon dance, art, education, philosophy, physics, psychology, and sports medicine. Devised by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel in 1815, Beethoven was an early supporter, but soon Maelzel's metronome (the original M.M.) inspired passionate debates amongst musicians, conductors, composers, pedagogues, and musicologists. Birkhold has successfully unveiled the deeper meanings of an innocuous device that spells out perfect time, as opposed to human time. An illuminating read.” —Fumi Tomita

>>How starfish move without a brain.

>>Other books in the excellent ‘Object Lessons’ series.

The Finest Hotel in Kabul: A people’s history of Afghanistan by Lyse Doucet $40

When the Inter-Continental Hotel opened in Kabul in 1969, it reflected the hopes of the country: a glistening white edifice that embodied Afghanistan's dreams of becoming an affluent, modern power. Five decades later, and the Inter-Continental is a dilapidated, shrapnel-damaged shell. It has endured civil wars, terrorist attacks, the US occupation, and the rise, fall and rise of the Taliban. But its decaying grandeur still hints at ordinary Afghans' hopes of stability and prosperity. Lyse Doucet, the BBC's Chief International Correspondent, has been staying at the Inter-Continental since 1988. She has spent decades meeting its staff and guests, and listening to their stories. And now, she uses their experiences to offer an evocative history of modern Afghanistan. It is the story of Hazrat, the octogenarian receptionist who for five decades has been witnessing diplomats and journalists, mujahideen and US soldiers, passing through the hotel's doors. It is the story of Abida, the first female chef to work in the Inter-Continental's famous kitchen after the fall of the Taliban in 2001. And it is the story of Sadeq, the 24-year-old front-desk worker who personifies the ambitions of a new generation of Afghans. The result is a remarkably vivid account of how ordinary Afghans have experienced half a century of disorder. [Paperback]

Read our latest newsletter

30 January 2026

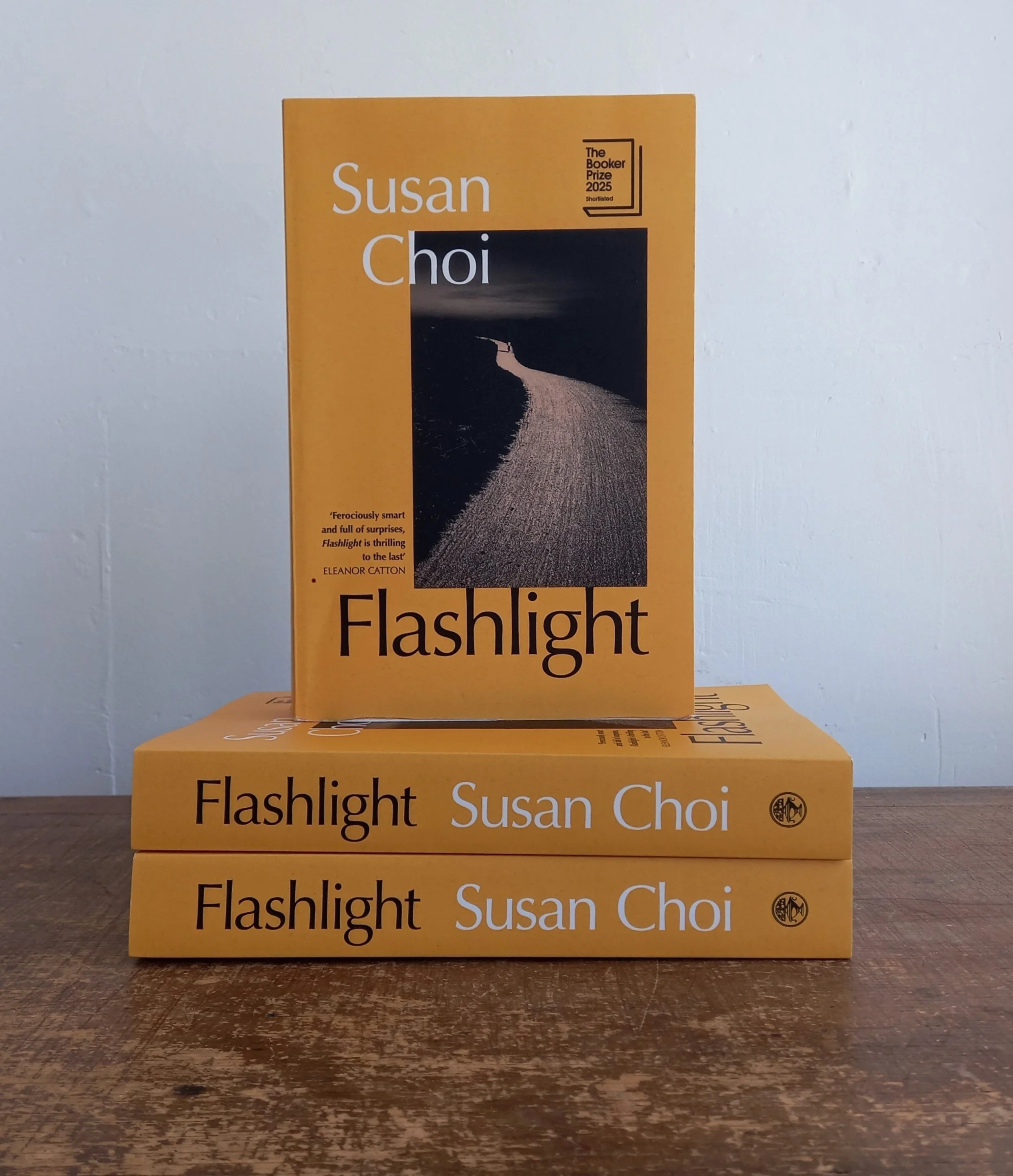

A night walking on the beach with her father Serk, looking at the stars, turns to tragedy for 10-year-old Louisa. Her father disappears, and is presumed drowned. She survives the tumult of the sea and is washed up on the shore, blue with cold, but in one piece aside from her memory of the evening’s events. Her last being the beam of the flashlight in her father’s hand, the light not revealing enough for a coherent story of what happened. Louisa and her parents have been living in Japan for the year. Louisa, although a conspicuously tall American-Korean child, had fitted in at school and her new neighbourhood. Unlike her mother, Anne, who struggled with the language, a husband who ignored her, and the onset of a degenerative disease. Serk and Anne had been at an impasse for a while, their relationship fraught and mechanical, sometimes violent. Each alone in their secrets and discontent. The distance and secrets continued to grow. Anne has made contact with Tobias, her son she had at nineteen, and doesn’t tell Serk. Serk is seeking his family, who left Japan to be repatriated to Korea, not to the island they were from, but to North Korea on the promise of a better life. A decision that Serk strongly disagreed with. In Flashlight, Choi swings the beam of the light from one to the other, taking us into the worlds and stories of each character. We head to the past. Serk’s childhood, where he is known as Hiroshi at school, and Seok by his family. (His name changes depending on his circumstances, Americanised, nickname, erased.) Here is the child that refuses to return to Korea, who thinks of himself as Japanese, but as a young man becomes embittered by his position in that society, and when an opportunity to leave comes, America beckons. Study and later a middling academic job. And a wife, and a child. We meet Anne, a girl mostly ignored, wanting something more than what is expected of her. Anne falls pregnant and her child is taken from her by the man she thought would save her from a dull life. Despite this deep sadness, she makes her way and is fiercely independent. Her marriage to Serk is another adventure, but one that after the first blush holds very little joy for her (or Serk) but they have Louisa. Louisa is cherished by both, but also caught in the crosshairs. She has Serk’s intelligence and Anne’s stubbornness. A fiery, as well as guilt-laden, relationship exists between mother and child; a tension that never resolves. Flashlight is a study in trauma, family dynamics, and in self. It’s outward and external in its telling of a piece of history of which I was oblivious (no spoilers here) and in relating the dynamics of this family unit with each other and in the world over several decades. It’s inward and internal in exploring the suffering, resilience, and resolve experienced by each of the main characters. There aren’t exactly happy endings here, but there is a sense of completion, which a less able novelist would have struggled with. This is a big novel — Flashlight is a novel that has much packed into it. Complex characters, with weaknesses and strengths; intriguing history which puts a spotlight on political power and nation-states; family relationships and secrets that hold no easy answers; and sharp writing that pulls it all together.

“Flashlight is a sprawling novel that weaves stories of national upheavals with those of Louisa, her Korean Japanese father, Serk, and Anne, her American mother. Evolving from the uncertainties surrounding Serk’s disappearance, it is a riveting exploration of identity, hidden truths, race, and national belonging. In this ambitious book that deftly criss-crosses continents and decades, Susan Choi balances historical tensions and intimate dramas with remarkable elegance. We admired the shifts and layers of Flashlight’s narrative, which ultimately reveal a story that is intricate, surprising, and profound.” —Booker Prize judges’ citation

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

All your choices are good! Click through to our website (or just email us) to secure your copies. We will dispatch your books by overnight courier or have them ready to collect from our door in Church Street, Whakatū.

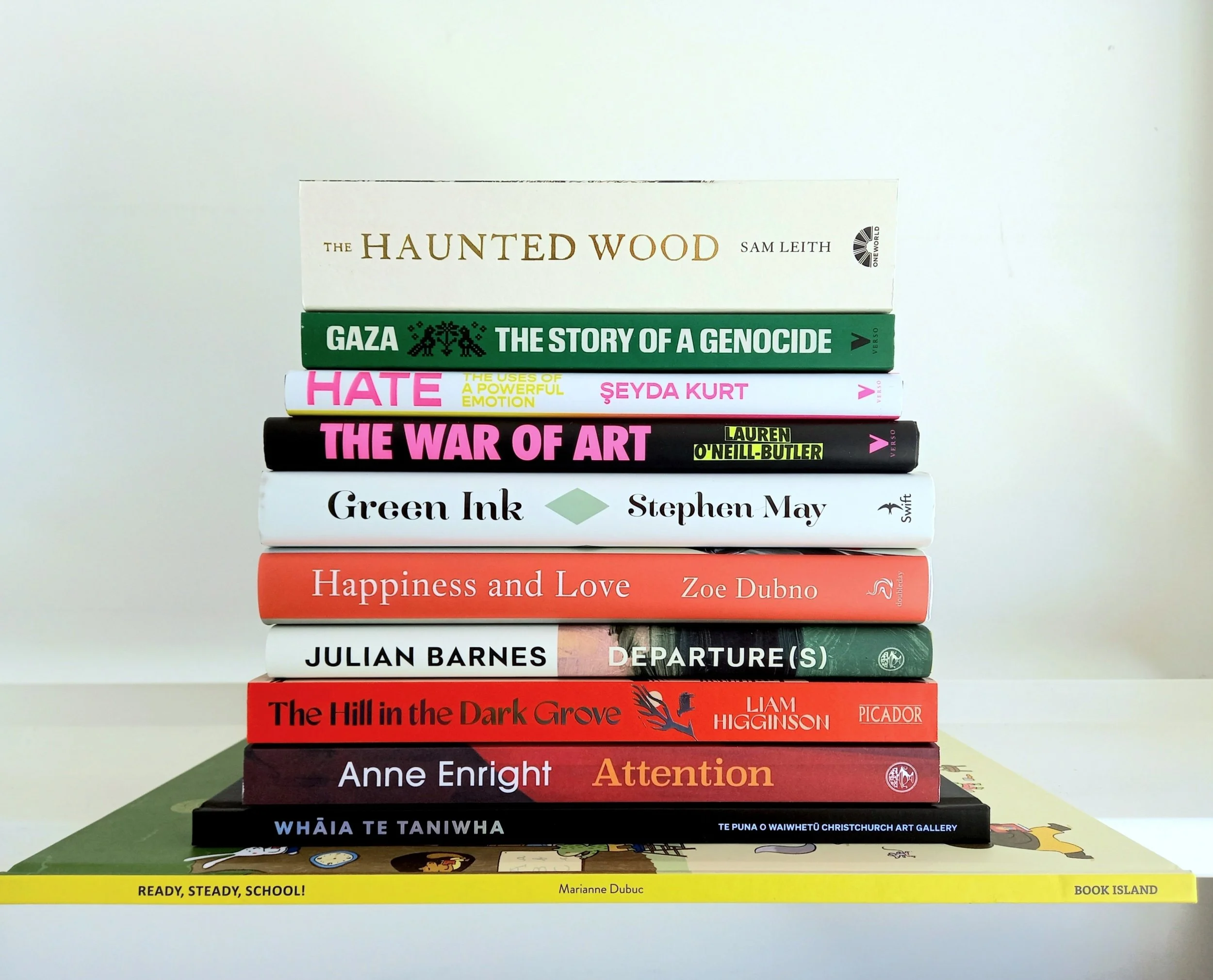

Happiness and Love by Zoe Dubno $38

An unnamed narrator who has fled a set of friends she despised, who bring out the very worst in her and each other, finds herself once more sat at their dinner table for a single, hideous evening. Years after escaping her unbearable artworld friends in New York for a new life in London, an unnamed writer finds herself back on the Lower East Side attending a dinner party hosted by Eugene and Nicole — an artist-curator couple — and attended by their pretentious circle. It's the evening after the funeral of their mutual friend, a failed actress, and if the narrator once loved and admired Eugene and Nicole and their important friends, she now despises them all. Most of all, however, she despises herself for being lured back to this cavernous apartment, to this hollow, bourgeois social set, for a dinner party that isn't even being thrown in their deceased friend's honour, but in the honour of an up-and-coming actress who is by now several hours late. As the guests sip at their drinks and await the actress's arrival, the narrator, from her vantage point in the corner seat of a white sofa entertains herself — and us — with a silent, tender, merciless takedown. [Hardback]

”As observant as a sniper, and just as ruthless, Zoe Dubno in Happiness and Love pulls off an unlikely yet ultimately very successful literary metempsychosis. Bernhard's fierce sarcasm and disappointment resonate very clearly in her voice; despite the distance that separates his 1980s Vienna from her contemporary New York, Dubno shows us — at times comically, at times despairingly — that the superficiality, hypocrisy, and flatness never change.” —Vincenzo Latronico

”Zoe Dubno examines character and human relations in the same way an art critic looks at a painting. Digging deeper and deeper into the thoughts behind thoughts, feelings behind feelings and questioning everything, Happiness and Love is an ecstatic performance of heightened perception.” —Chris Kraus

>>Read Stella’s review.

>>Cutting wood in New York.

>>The book is ‘based’ on Thomas Bernhard’s Woodcutters.

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes $38

Departure(s) is a work of fiction — but that doesn't mean it's not true. Departure(s) is the story of a man called Stephen and a woman called Jean, who fall in love when they are young and again when they are old. It is the story of an elderly Jack Russell called Jimmy, enviably oblivious to his own mortality. It is also the story of how the body fails us, whether through age, illness, accident or intent. And it is the story of how experiences fade into anecdotes, and then into memory. Does it matter if what we remember really happened? Or does it just matter that it mattered enough to be remembered? It begins at the end of life — but it doesn't end there. Ultimately, it's about the only things that ever really mattered — how we find happiness in this life, and when it is time to say goodbye. [Hardback]

”A moving, engaging book. Barnes’s humorous narrative explores the effect of time on love. A rather lovely swansong.” —Independent

”An elegant, thoughtful final book, which considers old age, fate and happiness. It's an arch blend of memoir and make-believe — and rather touching.” —The Times

”A richly layered autofiction. Artfully constructed to seem casually conversational, it braids erudite essayism and fiction, and every line is turned inside out with qualifications.” —Observer

”At a little over 150 pages, Departure(s) is brief but it is not slight and, each time I read it, I thought about it for days afterwards. If this is his [Barnes's] last book, he has given his career a triumphant ending.” —Financial Times

”Disparate elements are bound together by the skilful management of theme and tone. Departure(s) is at once confidently authoritative and tentatively questioning. Barnes assumes a personal relation with his readers, built on the kind of intimacy that cancer's company doesn't provide.” —Times Literary Supplement

>>Changing My Mind.

Attention: Writing on Life, Art, and The World by Anne Enright $40

Anne Enright has always been alert to the places where public and private meet, where individual lives are caught by, or alter, the sweep of history. These essays, collated from across Enright's career, take us from Dublin to Galway, Canada to Honduras, and through voices, bodies and time. They delve into Enright's own family history, and explore the free voices and controlled bodies of women in society and fiction. Enright has spent a lifetime reading as well as writing, and she offers new perspectives on writers including Alice Munro, Toni Morrison, James Joyce, Helen Garner and Angela Carter. Attention brings Anne Enright's wide-ranging cultural criticism, literary and autobiographical writing together for the first time. In Enright's fiction, speech can transform, rupture, enliven and liberate. [Paperback]

”With all its incisiveness, wit and brilliant sanity, Anne Enright's Attention provides a glorious antidote to the mad, sad world.” —Eimear McBride

”Anne Enright's essays are a joy to read: incisive, wise, often humorous, they are explorations of the way we live in the world today. I turned down so many page-corners as I read that I now cannot shut my copy of the book.” —Maggie O'Farrell

The Haunted Wood: A history of childhood reading by Sam Leith $30

Can you remember the first time you fell in love with a book? The stories we read as children matter. The best ones are indelible in our memories; reaching far beyond our childhoods, they are a window into our deepest hopes, joys and anxieties. They reveal our past — collective and individual, remembered and imagined — and invite us to dream up different futures. In a pioneering history of the children's literary canon, The Haunted Wood reveals the magic of childhood reading, from the ancient tales of Aesop, through the Victorian and Edwardian golden age to new classics. Excavating the complex lives of our most beloved writers, Sam Leith offers a humane portrait of a genre and celebrates the power of books to inspire and console entire generations. [Now in paperback]

”Sam Leith has been encyclopedic and forensic in this journey through children's books. It's a joy for anyone who cares or wonders why we have children's literature.” —Michael Rosen

”Scholarly but wholly accessible and written with such love, The Haunted Wood is an utter joy.” —Lucy Mangan

”One of the best surveys of children's literature I've read. It takes a particular sort of sensibility to look at children's literature with all the informed knowledge of a lifetime's reading of 'proper' books, and neither patronise (terribly good for a children's book) nor solemnly over-praise. Sam Leith hits the right spot again and again. The Haunted Wood is a marvel, and I hope it becomes a standard text for anyone interested in literature of any sort.” —Philip Pullman

Whāia te Taniwha: Kōrero from Te Waipounamu edited by Chloe Cull and Karuna Thurlow $30

Taniwha have shaped the land and navigated the waterways of Te Waipounamu for generations. They are shapeshifters, oceanic guides, leaders, ancestors, adversaries, guardians and tricksters who have left their marks on the land around us. Let the twelve Kāi Tahu artists and writers in this new book for rakatahi take you on a journey around the motu as we follow the tales of taniwha, both ancient and new. Weaving together te reo Māori and English, they explore how we can learn from taniwha — and what they can teach us about ourselves and our ever-changing world. Highlights: —A compelling introduction to taniwha for tamariki and rangatahi aged 8 to 15. —Stories located in Te Waipounamu South Island, by Kāi Tahu artists and writers. —Bilingual texts for te reo Māori speakers and learners alike, with a particular emphasis on te reo o Kāi Tahu. —Perfect for use by kaiako and ākonga in both English Medium and Māori Medium education contexts. Contributors: Justice-Manawanui Arahanga-Pryor, Leisa Aumua, Conor Clarke, Lucy Denham, A. J. Manaaki Hope, Meriana Johnsen, Moewai Rauputi Marsh, Waiariki Parata-Taiapa, Andrea Read, Jayda Janet Siyakurima, Ruby Solly, Paris Tainui. [Hardback]

>>Look inside.

Green Ink by Stephen May $40

David Lloyd George is at Chequers for the weekend with his mistress Frances Stevenson, fretting about the fact that his involvement in selling public honours is about to be revealed by one Victor Grayson. Victor is a bisexual hedonist and former firebrand socialist MP turned secret-service informant. Intent on rebuilding his profile as the leader of the revolutionary Left, he doesn't know exactly how much of a hornet's nest he's stirred up. Doesn't know that this is, in fact, his last day. No one really knows what happened to Victor Grayson — he vanished one night in late September 1920, having threatened to reveal all he knew about the prime minister's involvement in selling honours. Was he murdered by the British government? By enemies in the socialist movement (who he had betrayed in the war)? Did he fall in the Thames drunk? Did he vanish to save his own life, and become an antiques dealer in Kent? Whatever the truth, Green Ink imagines what might have been with brio, humour and humanity. [Hardback]

“May skilfully orchestrates a large cast of both historical and fictional characters. The novel's period detail is impeccable. One of its chief pleasures is the authorial voice, which, with its maxims on pity, ambition, boredom and so forth, is of an omniscience rarely encountered in contemporary fiction.” —Financial Times

”An idiosyncratic, rather dreamlike novel: it doesn't so much bring history to life as use a clutch of historical figures to showcase the author's own captivatingly offbeat intelligence.” —Jake Kerridge, The Telegraph

”A vivid and wholly credible recreation of post-Great War London. All is imagined here in convincing and sardonic — and frequently hilarious — detail.” —Robert Edric

”Stephen May is the spry, sardonic voice of the new historical fiction.” —Hilary Mantel

>>War, trauma, and politics.

>>A firebrand’s last day.

>>On Victor Grayson.

Gaza: The story of a genocide edited by Fatima Bhutto and Sonia Faleiro $30

"Genocide destroys cities and claims lives, but it also remakes the psyches of those it spares." The story of genocide belongs first to its survivors. In this urgent and powerful collection, Ahmed Alnaouq recounts the devastating loss of twenty-one family members. Noor Alyacoubi offers a searing account of starvation in Gaza. Mariam Barghouti examines the brutality of Israeli settler violence in the West Bank, while Lina Mounzer reports on the aftermath of Israel's simultaneous bombing of Lebanon. Their testimonies, along with those of many others, illuminate the enduring psychological and physical toll of state violence. Gaza: The Story of a Genocide brings together personal testimony, expert analysis, poetry, photography, and frontline reportage to document the full scope of destruction inflicted on the indigenous Palestinian people — their lives, their land, and their future. With illustrations by Joe Sacco and Mona Chalabi, it includes the work of the late poet Hiba Abu Nada, who was killed by an Israeli airstrike on her home in Khan Younis, Gaza, on October 20, 2023. Other contributors include Mosab Abu Toha, Susan Abulhawa, Laila Al-Arian, Tareq Baconi, Eman Basher, Omar Barghouti, Yara Eid, Huda J. Fakhreddine, Dr. Tanya Haj-Hassan, Yara Hawari, Maryam Iqbal, Nina Lakhani, Ahmed Masoud, Lina Mounzer, Malaka Shwaikh, Shareef Sarhan, and Mary Turfah. [Paperback]

Hate: The uses of a powerful emotion by Şeyda Kurt $37

Hatred is typically characterised as ugly, destructive and, above all, the political tool and dominant emotion of intransigent right-wingers. But is something important lost in this simplistic depiction? Don't those engaged in anticolonial, feminist, or class struggles — the very people who, in mainstream narratives, are usually portrayed as victims and objects of hate — have just reasons for feeling hatred? Şeyda Kurt, who approaches the topic from both personal and historical angles, challenges the consensual liberal perspective, reframing the exploited and oppressed as vehicles as well as targets of hatred. She weaves together the stories of Jewish avengers resisting German fascism, the Haitian revolutionaries, contemporary abolitionists, and many others, ultimately arriving at the revolution in Syrian Kurdistan and the question of a just peace. Kurt argues that the pursuit of justice is sometimes spurred by destructive impulses and hostility. What happens then to the tenderness we share as human beings? When we allow ourselves to hate, what becomes of the kindness we would bestow upon a world we are striving to protect? Kurt examines strategic hatred as a powerful force driving resistance, abolition, and even, paradoxically perhaps, radical care. [Hardback]

”A brilliant meditation on the relationships between hate, domination, and resistance. Kurt shows how the concept of hate is deployed to stigmatize and discredit anti-colonial, anti-racist, and feminist resistance, and how liberal moral stances against hate operate to pacify and to justify state violence through appeals to democracy and rule of law. This book is a vital tool for demystifying hate, so that we might see its role in liberation struggles.” —Dean Spade

>>Is hate politically useful?

The Hill in the Dark Grove by Liam Higginson $38

Carwyn and Rhian — the last in a long family line of sheep farmers — are living out a brutal year in their hillside farm, deep in the mountains of Eryri, North Wales. When Carwyn stumbles across a stone circle and some sort of burial mound in one of the fields on their land, he quickly develops an obsession. His wife, Rhian, meanwhile, is confronted with the growing realization that the man with whom she shares her life and home is slowly becoming a frightening stranger. As the harsh mountain winter closes in, Rhian finds herself alone with her increasingly peculiar husband, the mountains, and the looming megalithic stones. The Hill in the Dark Grove is a story of a lost way of life and the lengths we go to to protect what we know. [Paperback]

”Witty, tender, ultimately terrifying. Evocative and deftly done; The Hill in the Dark Grove is a book of echoes, haunted by the sheer vastness of time and landscape, and how they enact upon us and the stories we tell. A celebration of love's persistence, a summoning of ancient lore, a superb debut.” —Kiran Millwood Hargrave

”Liam Higginson is a new talent in Welsh storytelling; atmospheric, chilling and incredibly touching, The Hill in the Dark Grove holds the reader in its arms, and shows us how our stories, our objects and memories, are shaped and held by the land.” —Joshua Jones

”The Hill in the Dark Grove is a sumptuously written, dark meditation on aging, obsolescence, and the brutalising march of time and progress, as well as a chilling folk horror novel. There's something long buried in the mountains of North Wales and within the sheep herders, Carwyn and Rhian, who are economically pushed beyond their limits; Liam Higginson expertly brings it all to the surface.” —Paul Tremblay

The War of Art: A history of artists’ protest in America by Lauren O’Neill-Butler $45

Artists in America have long battled against injustices, believing that art can in fact "do more." The War of Art tells this history of artist-led activism and the global political and aesthetic debates of the 1960s to the present. In contrast to the financialized art market and celebrity artists, the book explores the power of collective effort - from protesting to philanthropy, and from wheat pasting to planting a field of wheat. Lauren O'Neill-Butler charts the post-war development of artists' protest and connects these struggles to a long tradition of feminism and civil rights activism. The book offers portraits of the key individuals and groups of artists who have campaigned for solidarity, housing, LGBTQ+, HIV/AIDS awareness, and against Indigenous injustice and the exclusion of women in the art world. This includes: the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), David Wojnarowicz's work with ACT UP, Top Value Television (TVTV), Agnes Denes, Edgar Heap of Birds, Dyke Action Machine! (DAM!), fierce pussy, Project Row Houses, and Nan Goldin's Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN). Based upon in-depth oral histories with the key figures in these movements, and illustrated throughout, The War of Art is an essential corrective to the idea that art history excludes politics. [Hardback]

”A wonderfully smart, readable and informative study of a topic that matters to almost everyone interested in art, which is more than enough to recommend it. But gems like the luminous chapter on Agnes Denes and the eye-opening revisionary discussion of her relation to Smithson make it something even better. Essential reading.” —Walter Benn Michaels

Ready, Steady, School! by Marianne Dubuc $48

A wonderful large-format search-and-find book. Next year, Pom will be starting school. But a year's too long to wait when you're excited. Today, Pom has decided to visit some friends by dropping in on different animal schools. At Little Leapers, the rabbits are learning how to read, write and count. At Bulrushes, the frogs are creating beautiful artwork. At F is for Foxtrot, the foxes are playing different sports.. What if Pom's dream school was a little bit of all that? One thing's for sure: school is an amazing adventure! This book is perfect for those keen to start school and for those who might need a little reassurance. [Hardback]

>>Look inside!

Read our 465th newsletter

23 January 2026

This evocative, heart-breaking, and revealing story of grief lays bare the genesis of Shakespeare’s most famous play, Hamlet. Yet in Maggie O’Farrell’s novel, Hamnet, Shakespeare as we know him hardly has a role. Set almost exclusively in the village of Stratford-upon-Avon and centred around the domestic life of his wife and family, Will is referred to as the Latin tutor, the glover’s son, the father, the husband. and is often working away — letters arriving at intervals. Who do we meet on the first pages, but the son — desperately searching for an adult to help him. His sister is unwell and the plague is present. From here, as time and the shadow of death make their presence known, we circle back increment by increment into the world of this child and his sister, of the mother, of the extended family and the village. We circle further back to the young Latin tutor gazing out the window, bored by the tedium of his job with boys who will never become any great things, and spying a youth (at first he mistakes his future wife for a lad) with a bird (later we meet this kestrel) upon her arm; and circle back again to the reasons why he is entrenched in this wearisome role — his violent and domineering father. Agnes is central and crucial in this novel. O’Farrell takes what little knowledge of Shakespeare's wife and brings her to the reader as a full and fascinating woman in her own right. She reels from the pages with her supposed eccentricities — she is a gifted healer, a lover of plants and the wilderness (seen by some in the community as a wild thing — a woman shunned by some but needed by others) — and her independent life. Emotional and emotive, sly and quiet, when death visits at her door, her grief is unbounded. Life has been snatched from her in a startling and, to her, an uncomprehending way. Agnes and Hamnet hold you in the grooves of this novel, make you want more, and they will stay with you long after the covers are closed. You reside within Hamnet’s mind as he navigates his twin sister’s illness, as he tries to find sense in the madness of the fever and the adult world that stands just outside his grip. You walk alongside Agnes as she loses herself in nature’s wildness to emerge into a world that can only tear at her, yet is necessary for survival and the memories that bind her child to her. Each character offers up a story — a way of seeing this world and telling its tale — a tragedy wrapped in intrigue on a small stage with rippling emotions. Hamnet is historical fiction at its best — in the vain of Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell series — it sets you fair and square in this time with all its life, death and drama. Immersive, compelling and rich in language and tale.

Perhaps the objects that carry the most meaning in our lives, the ones that are most imbued with the connections we have with the significant people in our pasts, the ones that both store and release the memories that are fundamental to our idea of ourselves, are not so much the precious heirlooms or heritage pieces but rather the ordinary objects that we use every day, just as, perhaps, their previous owners used them every day before us. The kitchen probably holds the greatest concentration of such useful-and-meaningful objects, come to us in many different ways, each with its own story. Bee Wilson’s thoughtful and beautifully written book tells the stories attached to 35 kitchen objects of many origins, and gives insight into the texture of the lives of the people who used them, and their importance to the people who use them now.

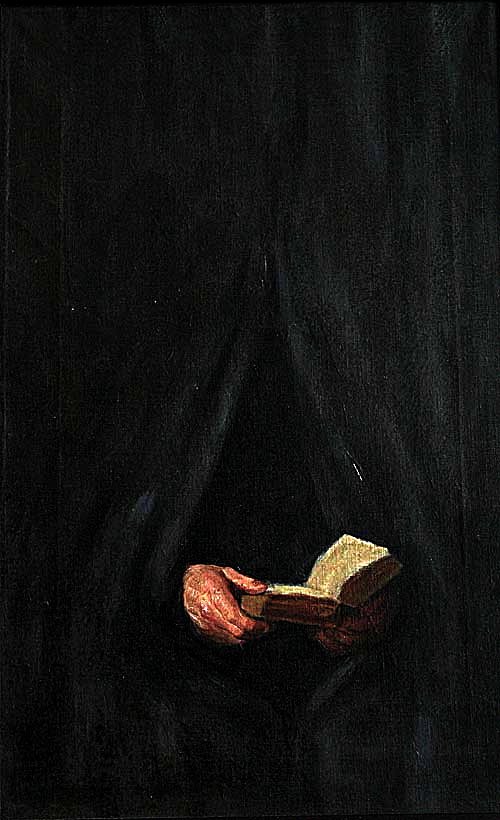

The hands holding the book in the painting by Markus Schinwald, and the black curtains between which they protrude, are painted in such a way as to make the viewer suspect that they are looking at a painting, or a part of a painting, by some Old Master, and the viewer, upon researching further, feels a little cheated to find that the artist is still alive. Had we perhaps confused even the name Markus Schinwald with that of some minor Germanic Old Master — perhaps a painter of agonising crucifixions, memento mori and surgically accurate Sts. Sebastians — which would have given this painting, in which the person holding the book into the light is effectively bodiless, concealed behind curtains, a disconcertingly suppressed reference to physical suffering? Maybe we should not feel cheated. Maybe it is the reference to the reference, by way of our confusion, that gives the painting, for us, its meaning.

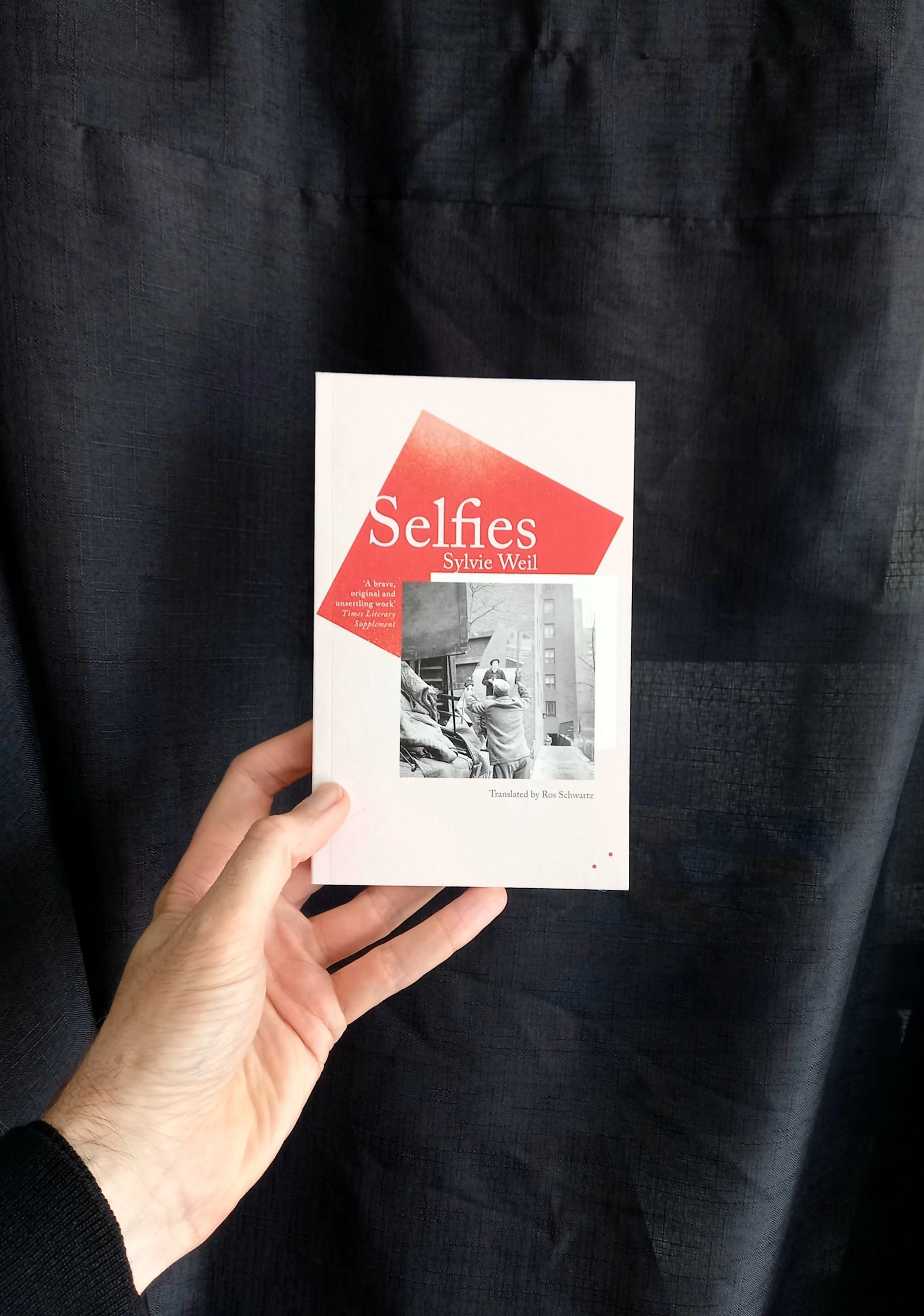

In the picture I didn't end up taking of myself I am sitting in an elderly armchair, the pile of its plush worn to the ghost of its original pattern on the arms and upper back. Beside me is a rather spindly green table upon which sits a vase of lilies, somewhat past their best, and a small empty coffee cup, a lip-mark of coffee at its rim. The sideboard behind me is stacked with books, and the fading light falls from my right onto the book I hold at an odd angle as if trying to postpone the moment in which I will have to get up and switch on a light. I am wearing something black and nondescript, seemingly a skivvy of some sort, liberally decorated with white cat hairs, and my head is thrust awkwardly forward over the oddly angled book, which I seem to be on the verge of finishing. Its title can be read despite the shadow: Selfies by Sylvie Weil.

*

The thirteen exquisite pieces of memoir that comprise Selfies each begin with a description of an actual artwork, a self-portrait by a woman ranging from the thirteenth century to today. This ekphrasis is followed by a description of a (possibly hypothetical) self-portrait by Weil which echoes or resonates with the historical work and provides a means of access to the third section of each piece, a more (but variously) lengthy examination of one of the more significant or uncomfortable aspects of Weil’s life. This tripartite structure demonstrates how viewing art can unlock new levels of understanding of our own lives, and how the communication of a stranger’s moment by means of a surface invariably stimulates the viewer’s memory to read that moment in terms of moments from the viewer’s own life, moments pressing at the surface of consciousness from the other side, so to speak. Viewing is remembering. The rigour and delicacy Weil demonstrates in viewing the artists’ works allows her to apply a similar set of criteria to her own memory-images, resulting in a remarkably nuanced set of realisations to be accessed and conveyed, potentially provoking a similar deepening of access in a reader to their his own memories. Weil’s prose, pellucidly translated from the French by Ros Schwartz, gauges subtle shifts of tone, frequently shifting our understanding of situations or persons before any knowledge about them is attained. The awful American mathematician with whom Weil had a love affair, her son’s mother-in-law, the close friend of her mother’s, the unsympathetic owners of a “Jewish” dog, are all revealed as having complex and often ambiguous relationships with the surfaces they present. Weil’s sentences, at once so straight-forward and so subtle, can move both outwards and inwards at once, operating at various depths simultaneously, as when Weil describes responses to her adult son’s mental breakdown: “I reply politely to friends who say: ‘I wouldn’t be able to cope if something like that happened to my son.’ I didn’t tell them that it could happen to anyone. And that they would cope, as people do. They’d have no choice. I don’t reply that they deserve to have it happen to them. Deep down, I agree that it is unlikely to happen to them. Not to them.” Precision often leads us to the verge of humour, as when Weil describes “the remains of a smile abruptly cut short, as if by the sudden and unexpected arrival of a dangerous animal.” The ‘Self-portrait as an author,’ springing from a description of a 1632 self-portrait of Judith Leyster seen as an advertisement for her portrait commissions (a commercial imperative), is a devastatingly perfect, almost Cuskian account of the people who visited Weil’s signing table at a literary festival. The book is full of images, or moments, details, that implant themselves in the mind of the reader and continue to resonate there in a way similar to the reader’s own memories. What is the purpose of self-depiction? “Everyone takes selfies,” Weil observes. “It’s a way of going unnoticed,” but at the same time each selfie is a form of searching, an attempt to locate oneself, somehow, in the circumstances that comprise one’s life. Memory is the only way we have to attempt to make sense of these moments.