When your cat looks at you like you’ve done her a disservice by not sharing your Friday night snacks, despite the fact they are not cat treats, you realise that the cat has tipped into personhood. No longer just a cat, but a person leveling a malevolent stare at you and eyeing up your glass of ginger beer. (Lucy doesn’t like ginger beer, but has been known to sneak a sip at a cup of tea.) (1)

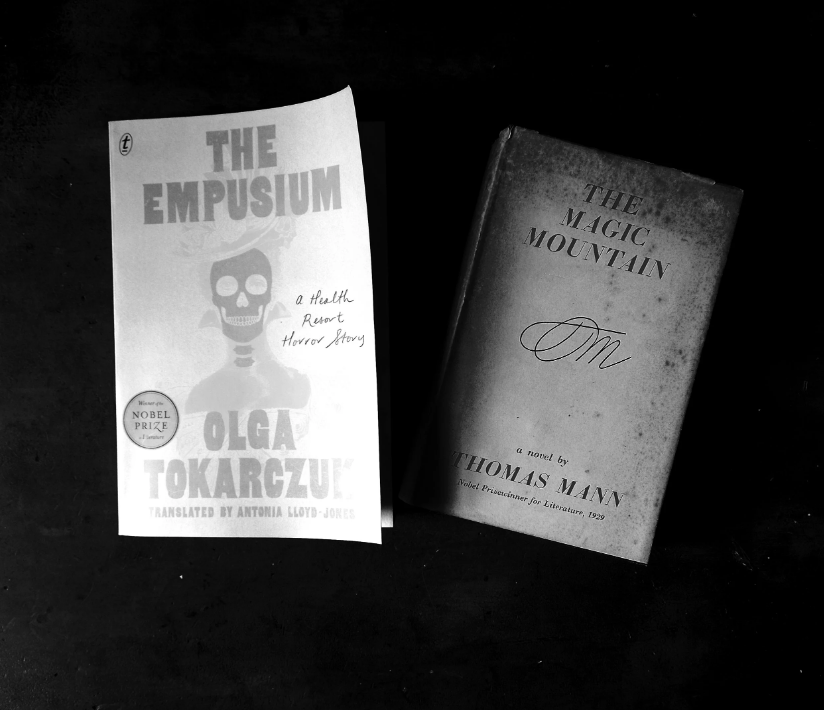

In Anna Jackson’s wonderful prose poem her hens feature throughout: their hen-ness evident on the page, and their personhood developing as the relationship between bird and human develops. But this is not an ode to hens, rather there are questions about what we think about when we think about (2) hens or contemplate our relation with domestic pets or our wider connection with nature. Don’t be misled for this is not nature writing, but then again it could be. (3) This is not a domestic poem, but it also is: — Jackson’s home and the familial feature on the page throughout the five seasonal sections. There is an autobiographical thread: Jackson’s thinking, her thoughts, the central cadence.(4). Yet this is not inward gazing, not a personal diary, rather a nod to diarists and keepers of memories. (5). And yet saying this I recall the poems about social anxiety, about uncertainty, about knowing. So I find myself saying it is a diary of sorts after all. Time plays its role. The collection is arranged by its five parts — five seasons — we travel from one summer to another. The ebb and flow not only being about time, but about the way thoughts arise and dissipate; how words work on the page, how poetry comes into being. Jackson’s reading (6) of other poets, essays, novels, non-fiction, philosophy mingle with her thoughts: — knowledge like residue landing in interesting places. Some profound, others extremely funny.(7). Terrier, Worrier: A poem in five parts is a deeply enjoyable and intelligent collection of thought-work and poetic good measure. It is as much about the idea of thoughts, of thinking, as it is about the thoughts themselves. Brilliant!

Notes:

1. Anna Jackson wrote these poems with a cat sitting on her lap.

2. This makes me think about What We Think about When We Think about Football (philosopher Simon Critchley) and What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (Murakami), and then I wonder about this turn of phase, and did it originate with Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love?

3. I discovered something about sparrows I did not know (and which will forever change my perception of them — in a good way!)

4. There is music. The whales that sing. The repeating lines “I thought”, “I wondered”, “I dreamed”, “I read” (but mostly “I thought”) tap out a steady and compelling beat.

5. Do read the Notes. They are fascinating.

6. Jan Morris, Olivia Laing, Ludwig Wittgenstein, social media, Carlo Rovelli, Virginia Woolf, Oliver Sacks, and more…

7. Pedal car.