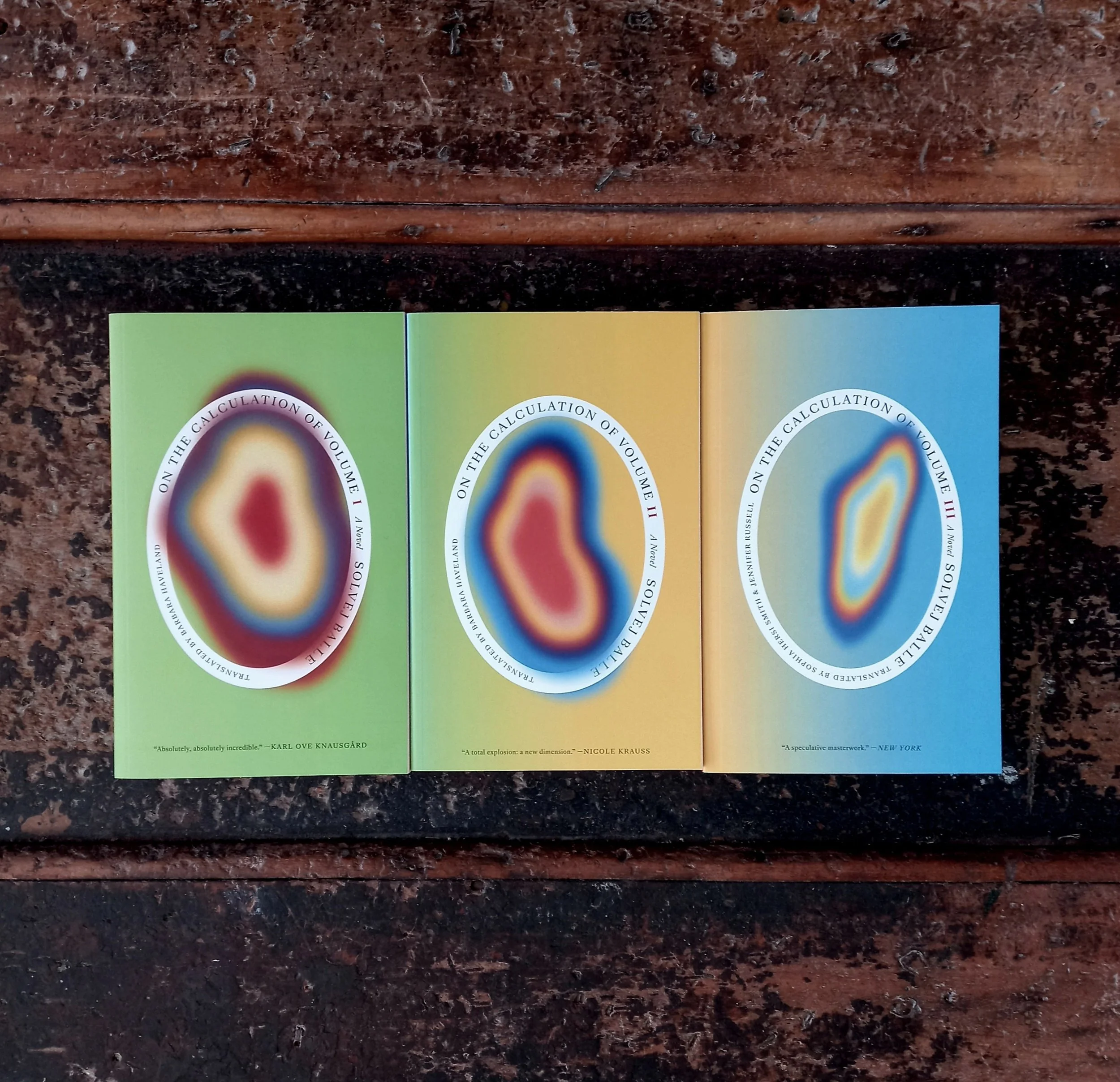

ON THE CALLCULATION OF VOLUME: 2 by Solvej Balle — reviewed by Thomas

How can I write my review, or live my life, or do anything without repeating myself, I wonder. Here I go again! My life seems to consist of smaller and larger circles of repetition, my days are filled mostly of content indistinguishable from that which filled and will fill other days, barring some disaster or some miracle that is, though I have only my experience of this moment, shaded with what I call memory, inflected with what I think of as anticipation, to give me any idea of this repetition. I do experience repetition, I experience time, as if it actually exists, but how can I bear this? Any generalisation about the state of the world is a subjective state, but I suppose this endless repetition gets things done, I am a cog in the world-machine or else an untoothed wheel spinning needlessly and without traction, it is hard to tell, but I get things done. Repetition is the mode of action, but it causes me more suffering than it should. I think that perhaps I do not like getting things done. I think that I could so easily slip out of this shuddering machine, any thing could provide a way out, observing anything without the illusion of context would release me from its meaning and allow me to see it clearly, without language, without intention, without usefulness, but for what? Would this be the ultimate dislocation from my world or the ultimate dissolution in it? We repeat ourselves to keep the middle way, to preserve the idea that we have of ourselves, or the idea that others have of us. Tara Selter, in Solvej Balle’s seven-part novel On the Calculation of Volume, finds herself trapped in an endlessly repeating 18th of November, or she repeats her presence in what everyone else experiences as a single day. In this second volume, Tara decides to travel through Europe, guided by a meteorological chart, pursuing the experience of a passing year by moving to places where the conditions on the 18th of November resemble those she would associate with a changed season. She travels north to ‘winter’ and south to ‘summer’ and records the fiction of a passing year in a green notebook in a sustained attempt to live against the facts. When the notebook is stolen and does not reappear, Tara concludes, “I have had no seasons. Seasons are not scenes and locations. You cannot construct a year out of fragments of November.” She considers a Roman sestertius that she has with her and “At that moment I felt a void come into being. I felt a loss, a slide, a shift. It was as if a space was opening up, very slowly, not a big space, or at least it didn’t feel big, but I couldn’t close it again.” There is a ‘looseness’ to the world, she realises, and she is simultaneously immersed and separate from it. “I am walking around the streets, superfluous and out of circulation. It is not a disaster. It is not nothing, but it is not much either. Even the sound of my own feet is superfluous. I am walking through a space that ought to be empty. The place I occupy ought to be vacant, but for some inexplicable reason Tara Selter has taken it. I am in the way, I am a foreign body, an error. I am a strange creature who ought not to be among people with a direction.” It is solipsistic to consider myself an intruder on my own absence, as Tara does, but I suppose we are all intruders on our own absence (or absences (it is hard to know whether not existing is entirely a personal thing or something I would share with everything else that did not exist)). Everyone in this 18th of November experiences the day each time the same (there is no reiteration for them, after all), except when Tara intrudes upon their world and they are affected or respond to her. The anomalies she brings to them change their day but have no effect, for there is no day after, or if there is, Tara cannot reach it. What would be the cumulative effect of all these anomalies, the effects of Tara, if these became compound and consequential? She is right to consider herself a monster, after all. What Tara consumes is not renewed, so although it may seem that she is free from the consequences of her actions, the world, however out of joint, offers her no such liberation. Her dilemmas are those in which we all find ourselves all the time, though our lives are constructed in denial of them. We can follow no thought through to its end. We live against the facts in order to stay within the limits of the space where we can get things done. “My time is not a circle and it is not a line, it is not a wheel and it is not a river. It is a space, a room, a vessel, a container,” writes Tara. Each volume of this remarkable book provides a space for our thoughts, and equipment to stimulate its exercise.