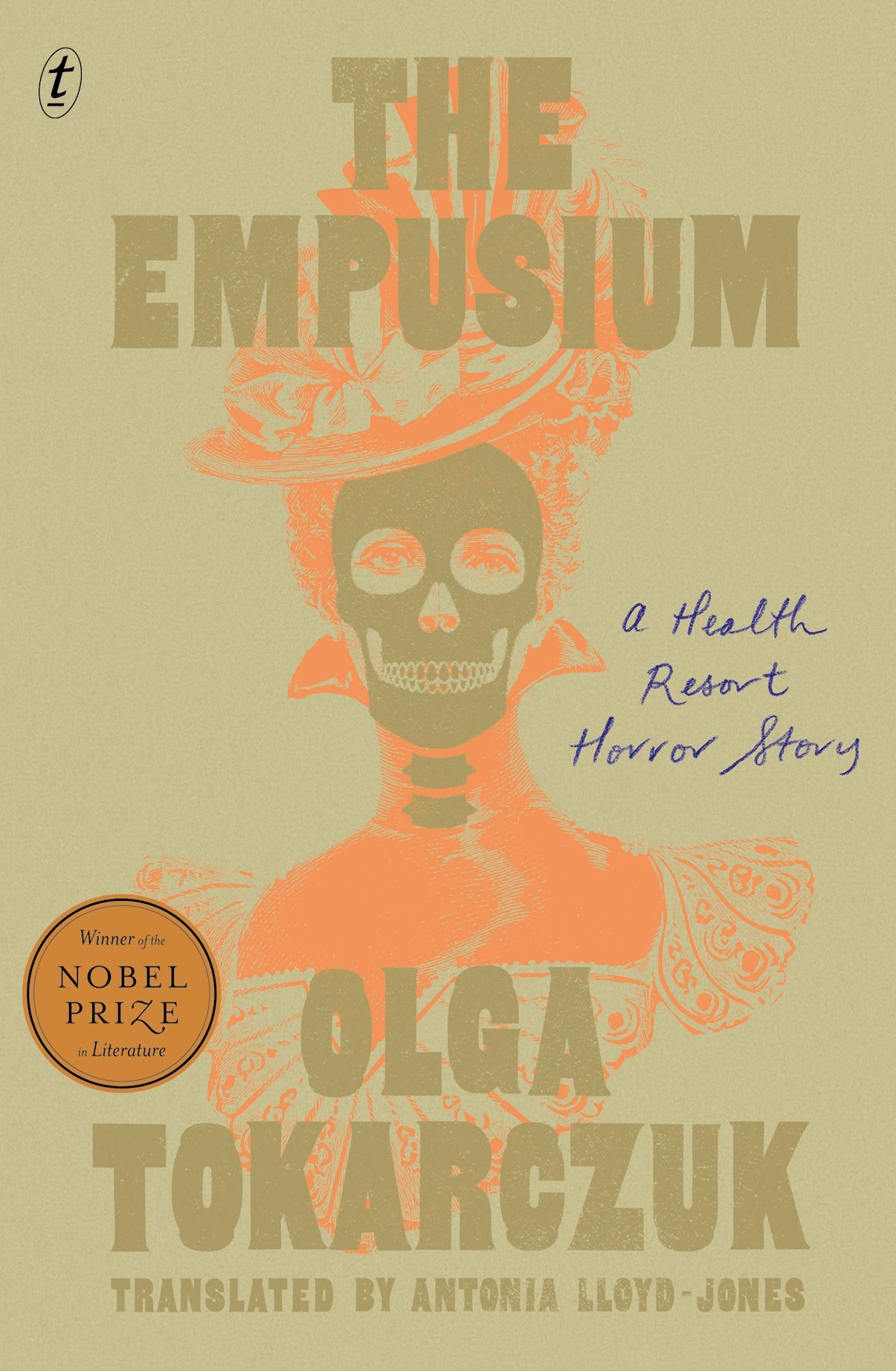

THE EMPUSIUM by Olga Tokarczuk — Review by Stella

From the opening pages, its gothic lettering contents page, an image of a carriage arriving in a small mountain village surrounded by forests, the looming buildings of the sanatorium, you feel as if you have entered the opening scenes of Nosferatu. Olga Tokarczuk’s novel The Empusium, subtitled A Health Resort Horror Story, builds intrigue from the outset. It’s 1913, a year before great turmoil, and curing tuberculosis is all the rage. Our young Polish hero, Mieczyslaw Wojnicz, has been sent to the Silesian village of Gorbersdorf for the fresh air, the cold baths and the expert advice of Dr.Semperweiss. The sanatorium is popular and full. Wojnicz takes a room at the more economical Guesthouse for Gentlemen run by the unseemly Optiz with help of a rugged lad, Raimund. Here his fellow guests, after a day of health procedures and walks in the village, sit down to dinner together. It’s an evening of conversation, often arguments, about existence, human behaviour, psychology, and politics; as well as the purpose of women or more accurately their flawed views on the inferiority of women. This topic of conversation, much to the surprise and annoyance of Wojnicz, who they take pleasure in warning and teasing, is a frequent and recurring theme, helped along by a local speciality, a mushroom-infused liquor— the hallucinatory effects fueling the conversation, as well as driving the gentlemen towards introspection. Wojnicz’s fellow housemates include a serial returnee who seems driven by ennui, a humanist bent on lecturing our dear young hero, a young student of art (dying), and the aptly nicknamed The Lion, his bombastic nature making him easy to dislike. Thrown into this dysfunctional playground, the timid Wojnicz is unnerved, and this is not helped by a suicide by hanging on his first day in the house. A house with strange creakings, with cooing in the attic and the whoosh of that new thing, electricity. Not to mention the horror chair with straps in the room upstairs, the graves in the cemetery with an abundance of November death dates, and the uncanny behaviour of the charcoal burners in the forests. Secrets abound, and Wojnicz has several of his own he’s keeping close to his chest. Tokarczuk builds this multi-layered tale from snippets of Greek mythology, the new ideas of the period (think Freud) and as a response to Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (published 100 years ago). Like Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead there is a mystery here, a fizzing at the edges, black humour, and a deadly serious exploration of ideas. While Drive Your Plow is pushing the idea of eco-activist in response to harmful tradition, The Empusium is examining the misogyny of the 20th century canon and by extension the influence of these writers, philosophers and psychologists on the contemporary intellectual landscape. To counter the conversations of the ‘gentlemen’, there is a wonderful sense of being watched, that things are not what they seem, and justice will be done. In Greek mythology, the Empusa were shapeshifting creatures. Appearing as beautiful women they preyed on young men, and as beasts devoured them. Beware of those that have one leg of copper, and the other, a donkey’s. As Wojnicz finds the Guesthouse increasingly repressive, the rigours of treatment intrusive, the hallucinogenic effects of liquor to be avoided, and the tragic decline of the young man Thilo unbearable, he also finds in himself a strength as to date untapped. Whether from curiosity, delusion, avoidance of his own fraught familiar relationships, or an unconscious desire to live, our hero explores the depths of the house and the village in an attempt to discover what drives the men of this village to act so horrifically. Add into this rich psychological horror, rich, fetid descriptions of the forest, its minutiae, the fungi and foliage, an atmospheric mindscape grows. Reading The Empusium is like looking through a telescopic lens, one that fogs over, but a twitch of the controls, and a whisk of a cloth, brings it all into sharp relief. If you haven’t read Tokarczuk, it’s time to start.