Michael Bennett’s finely tuned thriller opens with an historical atrocity before moving to a contemporary series of murders. Detective Hana Westerman is caught between being a good cop or a kupapa collaborator, and the cases become frighteningly personal. Excellently paced and populated by complex characters, this intricate novel centres on conflict between utu and on the aroha, hūmarie and manaaki needed to move forward.

>>Your copy.

We will be giving away a copy of the remarkable Renters United! / Lawrence & Gibson Publishing tabloid-format! illustrated! edition of Murdoch Stephens's biting and hilarious RAT KING LANDLORD with every book order we dispatch (until supplies are exhausted). And if you order a Lawrence & Gibson book we will put in a bonus copy!

>>Read Stella's review of RKL.

>>Books from L&G.

JANN MEDLICOTT ACORN PRIZE FOR FICTION

Better the Blood

Michael Bennett (Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Whakaue)

(Simon & Schuster)Kāwai: For Such a Time as This

Monty Soutar (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, Ngāti Kahungunu)

Mrs Jewell and the Wreck of the General Grant

Cristina Sanders

The Cuba PressBased on the true story of an 1866 shipwreck, this re-telling of the endurance of the survivors on a sub-Antarctic island is impeccably researched and peopled by rounded, realistic and complex characters. Dramatic and well paced, it is rich with vivid descriptions of sea, land and weather, and Cristina Sanders offers insight into the physical and psychological effects of being stranded in an inhospitable environment. Historical fiction at its best.

>>Your copy.

MARY AND PETER BIGGS AWARD FOR POETRY

Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised

Alice Te Punga Somerville (Te Āti Awa, Taranaki)

Auckland University PressAlice Te Punga Somerville’s meticulously crafted collection resonates with aroha, wit, sadness and anger. Advice to “italicise all of the foreign words in her poems” becomes a catalyst to exploring the dynamics of racism, colonisation, and writing in English as a Māori writer. Poems float like gourds strung with musings and personal recounts. English words incline as foreign words, but te reo syllables evade linguistic ambushes, camouflaged soundscapes and erasure. They stand upright, mark Space-Time like pou.

>>Your copy.People Person

Joanna Cho

Te Herenga Waka University PressJoanna Cho explores relationships, identity and survival with an aching, ironic honesty. A people person may have a name bought from a fortune-teller, drive battered cars, light up rooms with their hearts, or miss the smell of kawakawa ointment. Cho navigates expectations and choices in imagined and recalled stories, skilfully connecting folklore with autobiographical snapshots from South Korea and Aotearoa. Whimsical, surreal, magical and mundane elements meld and clash in poetic vignettes.

>>Your copy.Sedition

Anahera Maire Gildea (Ngāti Tukorehe)

Taraheke | Bush LawyerSedition flows through generations of dis-ease, enlivens tongues stilled by loss and trauma, excavates a genealogy of resistance. It’s a contemplative, defiant collection that resists the commodification of culture and whenua, and the ongoing perversity of neo-colonialism. Poems float upon the notion that we walk into the future facing our past, which embodies and shapes us. Anahera Maire Gildea agitates, untangles and reweaves threads of outrage, dystopia and anguish as she resolutely redraws detrimental power.

>>Your copy.We’re All Made of Lightning

Khadro Mohamed

We Are Babies Press, Tender PressKhadro Mohamed’s elegiac collection features a speaker torn between multiple worlds. Pendulating from prose to lyric, it is a ghostly work in which dreams and memory bleed into each other, as do its places: Egypt, Somalia, Newtown and Kilbirnie. Even time becomes concurrent, and for Mohamed, the past is right there in the present. In this collision of languages and worlds, the possibility and impossibility of home is both grieved and celebrated.

>>Your copy.

BOOKSELLERS AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND AWARD FOR ILLUSTRATED NON-FICTION

Jumping Sundays: The Rise and Fall of the Counterculture in Aoteroa New Zealand

Nick Bollinger

Auckland University PressWith its distinctive cover, bold typography and risograph hues on uncoated stock, this book demands to be read from page one. Weaving original sources into an engaging narrative, Nick Bollinger has crafted a considered and fitting history. Photographs from private collections add to its rich production, balancing text and illustration in ways that belie its size. Like the period it surveys, Jumping Sundays is a game-changer.

>>Your copy.Robin White: Something is Happening Here

Edited by Sarah Farrar, Jill Trevelyan and Nina TongaTe Papa Press and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o TāmakiThis is more than an exhibition turned art book. Stunning reproductions, historical essays and the insights of two dozen contributors do justice to the institution that is Robin White. As iconic screenprints flow seamlessly into large format barkcloth, White’s border-crossing practice is temporally divided with the savvy use of typographic spreads. Space, too, is given to the voices of her Kiribati, Fijian and Tongan collaborators. Strikingly elegant yet comprehensive, excellence is what’s happening here.

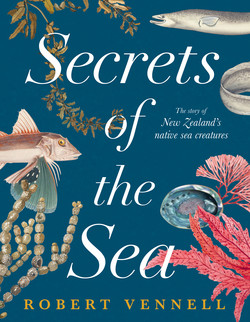

>>Your copy.Secrets of the Sea: The Story of New Zealand’s Native Sea Creatures

Robert Vennell

HarperCollinsSecrets of the Sea is a treasury of interesting facts, beautiful photography and remarkable prose. Beyond the luscious illustrations is a perfect blend of science, history and mātauranga Māori that gives the text depth and relevance and reveals in fascinating (and urgent) ways the interconnectedness of the human and extra human world. Visually compelling and hugely accessible, this impactful book will delight the marine biologist, sea aficionado and general reader alike.

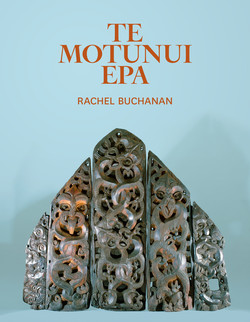

>>Your copy.Te Motunui Epa

Rachel Buchanan (Taranaki, Te Ātiawa)

Bridget Williams BooksInnovative and immensely topical, Te Motunui Epa is a triumph of storytelling and a challenge to the confines of traditional historiography. Rachel Buchanan’s meticulous research and compelling writing is complemented by the very best in graphic design – from its light-catching cover to the black-bordered array of archival documents. Generous while unafraid to confront the colonial hurt at the heart of the story, this is a deceptively powerful and enduring work.

>>Your copy.

GENERAL NON-FICTION AWARD

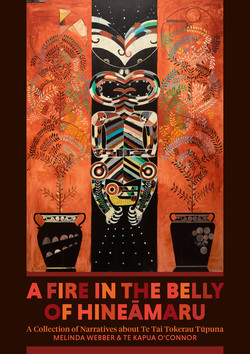

A Fire in the Belly of Hineāmaru: A Collection of Narratives about Te Tai Tokerau Tūpuna

Melinda Webber (Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Hau, Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whakaue) and Te Kapua O’Connor (Ngāti Kurī, Pohūtiare)

Auckland University PressAn exquisite and innovative book that uses a form of storytelling, pūrākau, to construct further stories that elucidate and challenge. It adds a layer of narrative truth to what we know about Te Tai Tokerau and, more importantly, shifts existing perceptions. It reveals the richness of knowledge in whakapapa which, especially for Te Tai Tokerau rangatahi, will spark significant personal and collective inspiration.

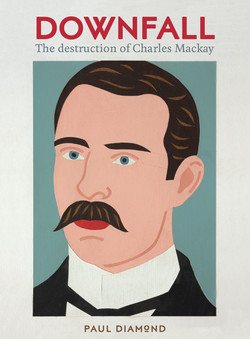

>>Your copy.Downfall: The Destruction of Charles Mackay

Paul Diamond (Ngāti Hauā, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi)

Massey University PressThis beautifully produced and generous book is a fascinating account of an extraordinary moment in small-town colonial New Zealand with its vivid line-up of characters, a revenge plot, blackmail and local Pākehā political intrigue. Alongside gripping, skilled and elegant popular historical storytelling, readers will find well-researched and closely observed insights into aspects of our national character, and our struggles with social decency.

>>Your copy.Grand: Becoming my Mother’s Daughter

Noelle McCarthy

Penguin Random HouseThis memoir presents both a woman confronting her own shame and the shame of generations with visceral honesty. It offers a treatise on forgiveness and a light of hope. Noelle McCarthy’s command of language imbues readers with sight, sound, smell and taste. It is complete as an individual narrative, while the centrality of the mother-daughter relationship and the weight that loads onto the process of knowing oneself offers much to our collective emotional intelligence.

>>Your copy.The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi

Ned Fletcher

Bridget Williams BooksNed Fletcher’s extensively researched and meticulously constructed book provides a valuable contribution to scholarship, history and law, and makes a timely and evolved interjection into the conversations of this country. Readers are led to evidenced conclusions via Fletcher’s clear hypotheses, structural commitment to reason and thorough examination of the characters and context involved in the creation of the English text of Aotearoa’s founding document.

>>Your copy.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

I’m re-reading Rat King Landlord in tabloid format complete with illustrations — it’s the Renters United! edition. Bravo, publishers Lawrence & Gibson! We are giving away a copy with every book order. Here’s my review of the paperback edition (2020): Ever wanted a crash course in Marxist theory, class structure, exploitation and capitalist advantage through property ownership, but found the reading a little too onerous? Well, then this novel is for you. Rat King Landlord, newly out of the excellent Lawrence & Gibson stable from the pen of Murdoch Stephens, is a satire that places you squarely in the continuing saga of our housing crisis — specifically the rental dilemma. Looked for a flat in Wellington lately; lived in an overpriced damp and mouldy house with strange flatmates and yet stranger landlord? — you need to look no further than here for a slice of almost-truth. Meet our flatmate, getting up early to make coffee in his haze of infatuation for Freddie, before she heads to work at the hip Broviet Brunion cafe located at the edgy end of the city, while flattie number three, Caleb, sleeps on, or whatever else he does, behind his closed door. So typical flatting life? Think again! Everyone wants to get on the property ladder, including the rats. Maligned and misunderstood, the rats are taking back the yard and the house. They are no longer content to live off your scraps while avoiding your traps. Rats have rights too! At the same time, strange posters are popping up all over the city advertising an event unlike any other — The Night of the Smooth Stones. Unauthorised and taking over billboard space owned by a corporate in cahots with the council, the posters resist being painted over or torn down. The message is oblique and the word on the street — well, on social media and in the huddled conversations of the politically leveraged hipsters — is that a revolution is about to hit the streets. Targets: property agents (loud hiss), landlords (hiss) and house owners (half-hearted small hiss). While the street is heating up, at home the temperature is rising too. The human landlord has died falling off a shonky ladder and his will results in the ownership of the house ending up in the hands (paws) of the Rat — the last being to witness him alive. Don’t even think about being animalist. As the Rat adjusts to his newfound status, learning English through texting (specifically with Caleb — the reclusive — who has an odd fascination with his Rat associate and an employer/employee relationship in due course — one that favours him over his flatmates), upgrading his shed, and making a slippery agreement to get himself into the house as a flatmate/landlord (alarm bells!), our protagonist becomes more agitated by the situation. Fire in the backyard, vigilantes on the street, pseudo-rebellion in the streets — who’s a landlord and who’s a renter? Have you got proof of your status or lack of? And the nights of rebellion just keep getting stranger. Who's behind the call to arms, and why is Freddie's boss acting weird? Rat King Landlord is a hilarious trip with a serious underbelly. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

Dust by Michael Marder (Reviewed by THOMAS} Dust: substance without form, or, rather, substance post-form, matter without identity, matter that has relinquished, or has been forced to relinquish, by abrasion perhaps, or fatigue, whatever identity it has most recently had, matter now adrift, out of place, bereft of form, bereft of nameability, other than as dust, not taking on another form, nor moving towards taking on another form, not taking on any of the set of identities that we associate with form, applying, as we do, identities to forms rather than to substance, matter that cannot be defined even as anything other than dust, a kind of dirt, but not a dirty dirt, a clean dirt, in other words a non-dirt, a self-negation, an oxymoron, a substantial nothing, an accumulation of entitilessness on the surface of an entity, a nonentity seeking to overwhelm an entity, evidence of entropy, evidence of the action of time upon everything our lives are made of, evidence that our world is contingent rather than ideal, that things slip away from under the ideas we fit to things, that ideas will always be disappointed in the actualities to which they are applied, even the relatively simple ideas that we call nouns, evidence that our ways of thinking and the ways of the world of which we think are not subject to the same laws, or to the same processes if what they are subject to are not laws, evidence that matter seeks release from time, release from form, for it is form that makes us vulnerable to time, evidence that matter above all grows tired and seeks to rest. Years ago I made notes towards what I intended to be a short book on dust, but this, fortunately for everyone, is now little more than e-dust among all the other e-dust in the world. Fortunately (in a positive sense), Michael Marder has written this interesting book, so, if you have any interest in dust, or in the universal processes that are evidenced in dust, I recommend you read it. |

NEW RELEASES

We will be giving away a copy of the remarkable Renters United! / Lawrence & Gibson Publishing tabloid-format! illustrated! edition of Murdoch Stephens's biting and hilarious RAT KING LANDLORD with every book order we dispatch (until supplies are exhausted). And if you order a Lawrence & Gibson book we will put in a bonus copy!

>>Read Stella's review of RKL.

>>Books from L&G.

What do we mean when we claim affinity with an object or picture, or say affinities exist between such things? Affinities is a critical and personal study of a sensation that is not exactly taste, desire, or allyship, but has aspects of all. Approaching this subject via discrete examples, this book is first of all about images that have stayed with the author over many years, or grown in significance during months of pandemic isolation, when the visual field had shrunk. Some are historical works by artists such as Julia Margaret Cameron, Dora Maar, Claude Cahun, Samuel Beckett and Andy Warhol. Others are scientific or vernacular images: sea creatures, migraine auras, astronomical illustrations derived from dreams. Also family photographs, film stills, records of atomic ruin. And contemporary art by Rinko Kawauchi, Susan Hiller and John Stezaker. Written as a series of linked essays, interwoven with a reflection on affinity itself, Affinities is an extraordinary book about the intimate and abstract pleasures of reading and looking.

>>The author's voice.

>>Alcohol and identity.

Enjoy browsing our annual VISUAL CULTURE SALE. This is your opportunity to pile up a selection of superb books on art, architecture, photography, design, theory, illustration, film, textiles, craft, and graphic novels, from both Aotearoa and overseas — all at satisfyingly reduced prices. Judging from previous years, our advice is: be quick — there are single copies only of most titles and many of them cannot be reordered (even at full price). >>Click through to start choosing.

Enjoy browsing our annual VISUAL CULTURE SALE. This is your opportunity to pile up a selection of superb books on art, architecture, photography, design, theory, illustration, film, textiles, craft, and graphic novels, from both Aotearoa and overseas — all at satisfyingly reduced prices. Judging from previous years, our advice is: be quick — there are single copies only of most titles and many of them cannot be reordered (even at full price). >>Click through to start choosing. This week we are featuring the books of the remarkable Norwegian writer Jon Fosse, who has developed a method he calls 'slow prose' to explore the depths and subtleties of memory and experience and to grapple with the complex predicaments of human existence, language, time, and personhood. His prose is hypnotic, looping, emotionally resonant, philosophical, and often also funny.

>>It's not me who's seeing.

>>The mystical realist.

>>A search for peace.

>>Pure prose.

>>Frames and levels.

>>Revisions and the ear.

>>A new name.

>>Thomas reviews The Other Name.

>>Septology (also available as The Other Name, I Is Another, and A New Name).

>>Trilogy.

>>Aliss at the Fire.

>>Scenes from a Childhood.

>>Melancholy 1—2.

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

The Other Name (Septology I—II) by Jon Fosse (translated from Norwegian by Damion Searls) {Reviewed by THOMAS} and I see myself sitting and reading the thick blue book of two parts, not that thick, actually, and I have reached that point in the book, though it is not in fact a point in the book for there is nothing in the book that would mark such a point, but rather a point in my reading of the book, which just happens to be around page seventy-five, that I came to realise that the book is written entirely in one sentence, one slow, patient, uninterrupted flow of words, no, I think, that is not correct, the book is written in two parts, though each begins with the word And, but neither part ends, each rather just leaves off, so it would not be correct that the book is written in one sentence, or in two sentences, one for each part, but rather in no sentences, one, or two, slow, patient, uninterrupted flow, or flows, of words, that much at least I got right, I think, just the kind of thing I like, but done with such virtuosity and with such little display of virtuosity that I had not realised until page seventy-five or thereabouts that there are no full stops to be found in this book, or no full stop, I am uncertain if this absence should be singular or plural, possibly both, this Jon Fosse and his translator Damion Searles having built these words without one misstep, or missomething, the metaphor seems mixed and I has not even realised that it was a metaphor, I must be more careful, capturing the flow of thought, so to call it, and speech, realistically, seemingly of the narrator, a middle-aged painter named Asle, living, I am almost tempted to put, as such people do, in a small town in western Norway, driving in the snow to and from a city on the western coast of Norway, the city of the gallery which shows, which is a euphemism of sorts for sells, his paintings, but also the city in which lives a middle-aged painter named Asle, resembling both in looks and clothing, if clothing is not part of looks, the narrator, the narrator narrating in the first person and this other Asle, the alter-Asle if you like, this alter-Asle to the thoughts and memories of whom the narrator-Asle has extraordinary access, though there is no evidence of any reciprocal mechanism, we are, I am sure, never given an instance of the alter-Asle even being aware of the existence of such a person as the narrator, this alter-Asle, being confined to the third person, and, I wonder, what sort of trauma confines a person to an existence only in the third person? presumably a trauma, I think, this alter-Asle being also an alcoholic and a person who “most of the time, doesn’t want to live any more, he’s always thinking that he should go out into the sea, disappear into the waves,” but not doing so because of his love for his dog, there is, I think as I am reading, some relationship between the two Asles, well, obviously there is, my thought, or the thought I have, being that the alter-Asle is the actual Asle and the narrator-Asle is the Asle that the alter-Asle-who-is-actually-the-actual-Alse would have been if he was not the Asle he became, which, I think, I have made sound a bit confusing, and the opposite of an explanation, not that that matters, on account of whatever trauma, or whatever it is that I speculate is a trauma, that confined him to a third-person existence, the characters being one character, all characters being one character as they are in all books, I speculate, though in this book The Other Name, almost all the characters have, if not the same name, almost the same name, which tightens the knot somewhat, if I can be forgiven another metaphor, though I will not forgive myself for it at least, I will try to avoid, I think, thinking of the relationships between these persons-who-are-one-person, or, in any rate, describing the relationships between these persons-who-are-one-person, in any way other than a literary way, whatever that means, nothing, I think, the person that Asle could have been sees the Asle that Asle became, though Alse cannot know him, the person that Asle could have been rescues Asle when he has collapsed in the snow and takes him to the Clinic and to the Hospital, and takes the dog to look after, who knows, though, if the third-person Asle, the one I was calling the alter-Asle until that became too confusing, at least for me, survives, neither we nor the first-person Asle know that, but after the first-person Asle goes to the city and rescues the third-person Asle from the snowdrift, how could he know where to find him, I wonder, he begins, in the second part of the book, to have access to some deeply buried memories of the Asle that perhaps they once both were, memories all in the third person, for safety, I think, memories firstly of Asle’s and his sister’s disobedience of their parents in straying along the shore and to the nearby settlement, a narrative in which threat hums in every detail, a narrative in which colour impresses itself so deeply upon Asle that, I think, he could have become nothing other than a painter, a narrative that seems searching for a trauma, for a misfortune, a narrative assailed by an inexplicable motor noise as they approach the settlement but which resolves with a misfortune that is anticlimactic, at least for Asle, a trauma but not his trauma, what has this narrative avoided, I wonder at this point, what has not been released, or what has not yet been released, I wonder, Fosse is a writer who writes to be rid of his thoughts, I think, just as his narrator says, “when I paint it’s always as if I’m trying to paint away the pictures stuck inside me, to get rid of them in a way, to be done with them, I have all these pictures inside me, yes, so many pictures that they’re a kind of agony, I try to paint away these pictures that are lodged inside me, there’s nothing to do but paint them away,” and, yes, when the narrator lies in bed at the end of the book and is unable to sleep, he does recover the memory, a third person memory, the memory of the trauma that split the Asles and trapped one thereafter in the third person, the memory that explains the awful motor noise that intruded on the previous narrative of disobedience as the children approached the locus of the trauma, and, I think, all the sadness of the book leads from here and to here |

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

|

VOLUME FOCUS : Women

A selection of books from our shelves.

Our Women on the GroundNEW RELEASES

>>Maintaining power imbalances.

"Machado De Assis is the writer who made Borges possible." —Salman Rushdie

"The greatest writer ever produced in Latin America." —Susan Sontag

"'Another Kafka." —Allen Ginsberg

"A great writer who chose to use deadly humor where it would be least expected to convey his acute powers of observation and his penetrating insights into psychology. In superbly funny books he described the abnormalities of alienation, perversion, domination, cruelty and madness. He deconstructed empire with a thoroughness and an esthetic equilibrium that place him in a class by himself." —New York Times

"Machado de Assis was a literary force, transcending nationality and language, comparable certainly to Flaubert, Hardy or James." —New York Times Book Review

>>The greatest writer the world has never heard of.

Artificial Islands tests the idea that Britain's natural allies and closest relations are New Zealand, Australia and Canada, through a good look at the histories, townscapes and spaces of several cities across the settler zones of the British Empire. These are some of the most purely artificial and modern landscapes in the world, British-designed cities that were built with extreme rapidity in forcibly seized territories on the other side of the world from Britain. Were these places really no more than just a reproduction of British Values planted in unlikely corners of the globe? How are people in Auckland, Melbourne, Montreal, Ottawa and Wellington re-imagining their own history, or their countries' role in the British Empire and their complicity in its crimes? Some in Britain see these countries as a natural fit for 'union' in the wake of Brexit, but would any of them be interested in such a thing? Interesting.Doll by Maria Teresa Hart $23

The haunted doll has long been a trope in horror movies, but like many fears, there is some truth at its heart. Dolls are possessed—by our aspirations. They're commonly used as a tool to teach mothering to young girls, but more often they are avatars of the idealised feminine self. (The word 'doll' even acts as shorthand for a desirable woman.) They instruct girls what to strive for in society, reinforcing dominant patriarchal, heteronormative, white views around class, bodies, history, and celebrity, in insidious ways. Girls' dolls occupy the opposite space of boys' action figures, which represent masculinity, authority, warfare, and conflict. By analysing dolls from 17th century Japanese Hinamatsuri festivals, to the '80s American Girl Dolls, and even to today's bitmoji, Doll reveals how the objects society encourages girls to play with shape the women they become.

>>Other books in the excellent 'Object Lessons' series.

>>Long-listed for the 2023 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

>>Other books in the excellent 'Object Lessons' series.

>>Meeting minds.

>>Read Stella's review.

>>Collapsing reality.

>>Joy Williams does not write for humanity.

>>Ecological ruin and postmodernism.

>>Reset.

>>A millennial's purgatory.

>>Fruitless taxonomies.

>>Where are the great climate novels?

>>See also Amitav Ghosh's The Great Derangement.

>>Uncanny the singing that comes from certain husks.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

|

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | ||

Aug 9—Fog by Kathryn Scanlan {Reviewed by Thomas}

|