The dual narratives in Lorrie Moore’s wonderful new novel act as calipers — one point in the post-Civil War period; one point in the chaos of 2016 — to inscribe the awkward, unsettling and ludicrous omnipresence of death in American culture. Whether describing a road trip with a protagonist’s undead love interest or the troubles that haunt a woman running a boarding house and hiding a secret one-and-a-half centuries earlier, Moore’s writing is better than ever — funniest when it is blackest; most incisive when applied to the unresolved and messy edges of experience.

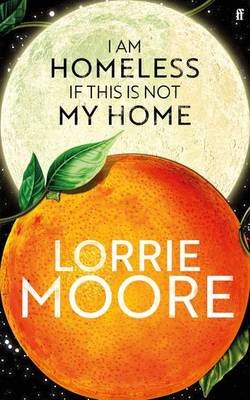

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore — reviewed by Stella

An enigmatic novel that is as compelling as its title. My first encounter with Lorrie Moore was another wonderfully entitled work, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? This was her second novel, published in the mid-90s, and revolved around a middle-aged woman’s bittersweet nostalgia for her young adolescent self. Centred around an amusement park the ferris wheel featured largely, always looming in the backdrop. I remember it for its sharp writing and keen observation. Moore’s fourth novel, I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, is even more closely observed and has such verve. It’s a wild ride — elegiac and metaphysical. It’s intriguing and mystifying. Just as you start to pin it down it whirls off, angling towards something just beyond. It’s 2016. America is tipping itself into the abyss. Finn, a teacher on enforced leave (his state of mind is far from perfect), is attending to his brother at a hospice until he is called away by a call from his ex-girlfriend’s book group chum. But wait! The first chapter is a million miles from this. Someone is writing a letter. The language is arcane. The tone familial. It’s a letter to her dear sister. As we read on, we deduce that the letter-penner is the landlady of a boarding house near the close of the American Civil War. It’s a letter of complaint and later (more letters follow interspersed with Finn’s story) confessional about her interactions with one of her lodgers and his eventual death. And death or, more accurately, loss, is at the centre of this novel. Finn is lost, his brother is losing the battle to stay alive, his ex-girlfriend, Lily, is in limbo — well, actually, she is undead, and the landlady’s confession reveals a death. Sounds a bit glum? Well, it’s not. It’s hilariously funny in the way that the macabre can be and the relationship between Finn and Lily (after she’s risen out of the dirt, a few worms in situ, from the green cemetery) is charged with energy and, dare I say it, life, as they embark on a road trip to find her final resting place. The dialogue throughout the novel, whether it’s Finn clumsily attempting to cheer up his brother, the banter about how Lily looks in her undead guise, or the landlady’s dismissal of her lodger, is sharp and sparking with energy. The observations of human weakness, kindness, and contempt (Lily is a thorny prospect dead or alive), are wry and sometimes devastating. On these lunatic fringes, we are all standing on the edge watching others go before us. Moore reminds us we might fall in. But then again, we could always go home.

Grove, A field novel by Esther Kinsky (translated from German by Caroline Schmidt) — reviewed by Thomas

“Absence is inconceivable, as long as there is presence. For the bereaved, the world is defined by absence,” she wrote. She went to Olevano, some distance from Rome, in the hills, in the winter, two months after her partner died, the bereavement was taking hold, she no longer fitted into her life. It was winter, as I said, she stayed alone in Olevano, she looked out of the window, she went for walks, she took photographs, she wrote. The whole place, and the text she wrote, was cold, damp, dim, filled with mist, vagueness, echoes, mishearings. Well, of course. This is not to say that her observations were not precise, preternaturally precise, and the sentences she wrote to describe them, they too were preternaturally precise, whatever that means. “In the unfamiliar landscape I learned to read the spatial shifts that come along with changes to the incidence of light.” She is unable to think of the one who is lost, rather, the one she has lost, she is unable to face an absence that at this time is an overwhelming absence, instead she observes in minute detail, with great subtlety, as if subtlety could be anything but great, the particulars of the day and the season, the fall of light, those things that only she could notice, or only a bereaved person could notice, the weight of noticing shifted by her bereavement, death pulling at everything and changing its shape, changing the fall of light, even, or making her aware of changes in the fall of light, and in the shape of everything, so to call it, that are inaccessible to the non-bereaved. There are other worlds, but they are all in this one, wrote Paul Éluard, apropos of something, if it was him who wrote it, and if that was what he wrote, if these are different things, but as we can cope with the world only by suppressing almost everything that comes at us, even at best, we notice only as our circumstances allow, our mental circumstances, our emotional circumstances perhaps most significantly, and we are somehow sharing space but seeing everything differently from others and some more differently than others. We live in different worlds in the same world. She was bereaved, she saw what she saw, observed what she observed, with great precision and intensity as I have said, out of the mist, among the fallen leaves. There is a cemetery in every town, or vice-versa, she visits them all, acquaints herself with the faces of the dead, but not her dead, not the one of whom she is bereaved. She writes of herself in a continuous past, “I would.” she writes, “Each morning I went,” she writes, as if also all that is observed also continues in this continuous and unbordered way, which might be so. Death, first of all, is an aberration of time, bereavement acts on time like a point of infinite gravity that cannot be observed but which bends all else. Memories are the property of death, there can be no memories if she is to face each day, though the memories pluck at her in her dreams. She observes, she wanders, she acts on nothing, she changes nothing, the season moves slowly through darkness and chill. She travels to the nearby towns and into the hills, the mists. She recognises herself more in those displaced like her to Italy, the migrants and the refugees, those for whom no easy place welcomes them, those who have lost something, recently, that the others around there have perhaps not recently lost. “We sized each other up as actors on a stage of foreignness,” she writes, “Each concerned with his own fragmented role, whose significance for the entire play, directed from an unknown place, might never come to light.” She is aware, everywhere, of the loss that outlines and gives shape to that which goes on, and the mechanisms of loss that are built into the function of a whole town, or a whole human life. She sees the junkyard by the bus station, “an intermediate space for the partially discarded, whose time for final absence has nevertheless not yet arrived.” She visits the Etruscan tombs and sees the reliefs there as a membrane separating the living from the dead, their loss is one of space as well as of time, what is shared between her and them is two dimensional only, “as if the dead would know how to reach through the cool thickness of the masonry to touch the object’s or animal’s other side, invisible to us, and hold it in their life-averted hands.” The membrane is infinitely thin. It is only two dimensions. It is everywhere. She asks, “Will it wither away, the hand I pull back from the morti?” Time passes. Something unobserved is changing beneath the changes she observes, “the Spring air a different shade of blue-gray.” She leaves Olevano and leaves the first section of the book. Because she, we, you, I perceive only a fraction of what we could call the external, the fraction to which we are at a moment attuned, it is easy to fall out of tune with others. For her, whom bereavement has differently attuned, or untuned, her reattunement must be achieved by words, she who lives by words must recalibrate her world through words, descriptions, care, precision, nuance, it is wrong to think of nuance as somehow imprecise, it, all this, is an exercise in slowness, and we who read must also change our speed to the speed of her noticing if we are to experience the text, if we are to experience, through the wonder of her text, somehow, her experience, or something thereof. The external reveals itself only to those moving at the precise right speed of perception, so she shows us, and so too her text reveals itself only to those moving at the precise right speed, those who read the text at the speed the text requires. In the second section she remembers, memory being the province of death, or vice-versa, her father, of whom she has also been bereaved, a little longer ago, and the holidays in Italy of her childhood, with him, and, presumably, with her mother, though this section deals specifically with memories of her father, perhaps because her mother is still alive, if she is still alive. This section is the section of the father, of the memories of the father more particularly, the only way her father now exists, he has finished contributing to memories that might be had of him and fairly soon these memories become the memories of memories, the parts magnified becoming still more magnified, the other parts abraded, becoming lost. Each memory contains a necropolis, it seems. With nothing, she begins the third and final section. She rents a cottage, so to call it, in the delta of the Po. Marshes, salt pans, mists again, fogs, rains. Birds. It is winter. “Everything had been repeatedly disturbed, was forever suspended between traces and effacement.” All that is human, and all of nature is abraded. “It was even hot when I arrived, the air similarly gray and viscous, and the landscape lay motionless, disintegrating under its weight; on hillcrests and in the occasionally visible strips of riverbank clung fragments of memory that had been torn away from a larger picture and settled there.” Time moves differently, again, here, she lets it, broken things stand about, the past is forgotten but is everywhere, is in the dust and mud, more often mud, the rain, the fog. “It was a place that could only be found in its absence, by recalling what was lost, therein lay its reality.” But here in this slow nowhere something almost unperceived begins to change, the emptiness provides a space, the past gets somehow out of her, death begins not to completely overwhelm her, memory relinquishes something of its choke. She even gets a ride to town with the owner of the cottage, in his car. Perhaps she comes to think that history is the proper province of the past. “Among the places of the living are the places of the dead,” she says, and not vice-versa nor one inside the other. She visits Ravenna and in Ravenna the two mosaics spoken of to her by her father not long before his death, actually the last time she saw him before his death. The mosaics are now outside her, sensed, and no longer trapped inside, her father’s experience of the two blue mosaics likewise no longer trapped, the experience of her father, something of a connoisseur of blue, no longer confined inside the one who is bereaved, the bearer of his memory, but somehow shared with her. These two mosaics, I wonder, for her, also a connoisseur of blue, are, perhaps, the mosaic of life and the mosaic of death. “These two mosaics — the dark-blue, bordered harbour with its still unsteady boats; and the light-blue expanse with no obstruction, nothing nameable, not even a horizon.”

New books — just out of the carton! Click through for your copies now.

Audition by Pip Adam $35

Audition is hurtling through space towards the event horizon. Squashed immobile into its rooms are three giants: Alba, Stanley and Drew. If they talk, the spaceship keeps moving; if they are silent, they resume growing. Talk they must, and as they do, Alba, Stanley and Drew recover their shared memory of what has been done to their incarcerated former selves. Or are they constructing those selves from memory-scripts that have been implanted in them? Part science fiction, part social realism, Audition asks what happens when systems of power decide someone takes up too much room – and about how we live with each other’s violences – and imagines a new kind of justice.

”In parts sci-fi, absurdist, fabulist, social realist—although all attempts to categorise fall short and do the novel a disservice—this is exciting and inventive writing in the hands of an extraordinary writer. Readers may find themselves equal parts unmoored and floored by this thrilling novel. I haven’t stopped thinking about it.” —Deborah Crabtree

>>”My work always comes from somewhere else.”

>>Constraints and space.

The Planetarium by Nathalie Sarraute (translated from French by Maria Jolas) $33

A young writer has his heart set on his aunt's large apartment. With this seemingly simple conceit, the characters of The Planetarium are set in orbit and a galaxy of argument, resentment, and bitterness erupts. Telling the story from various points of view, Sarraute focuses below the surface, on the emotional lives of the characters in a way that surpasses even Virginia Woolf. Always deeply engaging, The Planetarium reveals the deep disparity between the way we see ourselves and the way others see us. A key work in the history of the French modernist novel (first published in 1959); the English translation is back in print at last.

”Sarraute’s ability to capture those fleeting impulses that rise to the surface of consciousness only to be immediately resubmerged, or which settle on the surface of consciousness (consciousness being necessarily a surface, I suppose) only to immediately take flight towards another surface, gives insight into the primal, almost organic emotional flux that underlies (or overarches) what we commonly think of as individual personality. Even the most complex of our interactions is compounded of impulses barely distinguishable from nothing.” —Thomas

”The best thing about Nathalie Sarraute is her stumbling, groping style, with its honesty and numerous misgivings, a style that approaches the object with reverent precautions, withdraws from it suddenly out of a sort of modesty, or through timidity before its complexity, then, when all is said and done, suddenly presents us with the drooling monster, almost without having touched it, through the magic of an image." —Jean-Paul Sartre

>>Read Thomas’s review of Tropisms.

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore $35

A teacher visiting his dying brother in the Bronx. A mysterious journal from the nineteenth century stolen from a boarding house. A therapy clown and an assassin, both presumed dead, but perhaps not dead at all… With Moore’s distinctive wordplay and singular wry humour, this book is a magic box of longing and surprise — about love and rebirth and the pull towards life.

"Is it an allegory? Is it real? It doesn't matter. Exploring sibling love, death, and longing, it's a novel with big questions, no answers, and it's absolutely brilliant." —Emily Firetog

”Moore's sterling literary reputation is anchored most firmly to her short stories, but in her long-awaited fourth novel, her prose is just as breathtakingly crystalline, her humor wily and piquant. A curious spin on Faulkner's As I Lay Dying, with frissons of George Saunders's Lincoln in the Bardo), Moore's unnerving, gothic, acutely funny, lyrically metaphysical, and bittersweet tale is an audacious, mind-bending plunge into the mysteries of illness, aberration, death, grief, memory, and love." —Donna Seaman

"Moore is revered for her wit, and fans will not be disappointed by the novel's dark humour. The prose might be her finest." —Claire Messud

”Moore manages the impossible in her writing: every other sentence is a gut-punch or the funniest line you've ever read, and it coheres into some of the truest writing about life-for what is life if not constantly either hilarious or devastating, and often both? I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home is a ghost story, a love story, a family elegy, and a search for answers both tangible and ephemeral: it's the world of Lorrie Moore, beckoning us back in." —LitHub

>>New possibilities.

Na Viro by Gina Cole $35

Appearing before the head of the Academy for fighting at her graduation ceremony, puffer ship navigator Tia Grom-Eddy must either join the crew of a spaceship on a deep space mission or complete a lengthy probationary period on Earth. Mortally afraid of travelling into deep space, Tia chooses probation. Estranged from her parents, Tia is bereft when her sister, Leilani, joins the crew of a puffer fish spaceship sent to investigate a whirlpool in deep space. And when the cosmic whirlpool sucks Leilani’s shuttle into its grip, Tia must overcome her fear of space travel and find a way to work with her mother, who is leading the rescue, or risk losing her sister forever. A science fiction fantasy novel and a work of Pasifikafuturism from the author of Black Ice Matter.

>>Outer space through a Pasifika lens.

>>Put on hold.

A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir (translated from French by Patrick O’Brian) $35

Long considered one of Simone de Beauvoir’s masterpieces, A Very Easy Death is a profoundly affecting, day-by-day recounting of her mother’s final days after she is hospitalized following a fall. Though a devout Catholic, her faith is subsumed by her terror of death, and as her body fails, she clings to life with fierce, primal desperation. In depicting her mother’s refusal to ‘go gentle’ while her autonomy and dignity are taken from her, Simone de Beauvoir “shows the power of compassion when it is allied with acute intelligence” (Sunday Telegraph). Powerful, touching and sometimes shocking, this is an end-of-life account that no reader is likely to forget. With an introduction by Ali Smith.

”True, and deeply moving.” — Annie Ernaux

”Nowhere is de Beauvoir’s rigorous honesty more visible than in this haunting account of the death of her mother... As she charts her last weeks and her abasement at the hands of doctors and illness, both hostility and unexpected love play themselves out on the page.” — Lisa Appignanesi

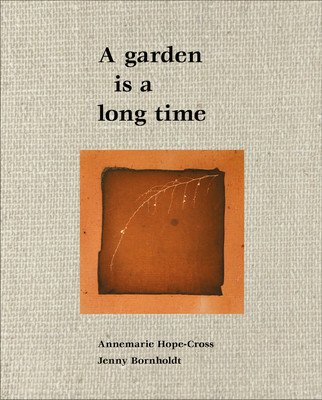

A Garden is a Long Time by Annemarie Hope-Cross and Jenny Bornholdt $50

The photographs in A garden is a long time take us beyond the perimeter of the Central Otago garden where they were created. Incorporating processes and materials from the darker, more mysterious corners of early photographic history, the images offer an account of the life and sensibility of a remarkable artist, Annemarie Hope-Cross (1968–2022). With Jenny Bornholdt’s poetry and prose treading deftly around the edges of Annemarie’s life and photographic work, A garden is a long time is a meditation on time, light and the spaces we all inhabit. For Hope-Cross, photography was, at once, a science and a miracle; the camera was an echo chamber and each photograph was a place where past and present met, where the living communed with those lost along the way, and where the most ordinary plants and objects were rendered mysterious, at times radiant. These photographic exposures, and the words that accompany them, are the heartfelt measure of an hour, a day, a season, a lifetime.

>>Look inside the book!

>>Portfolios of Hope-Cross’s photography.

Collected Works by Lydia Sandgren (translated from Swedish by Agnes Broome) $37

Martin Berg is slowly falling into crisis. Decades ago, he was an aspiring writer who'd almost finished his novel, his girlfriend was the shockingly intelligent and beautiful Cecilia Wickner, and his best friend was the up-and-coming artist Gustav Becker. But Martin's manuscript has long been languishing in a desk drawer, Gustav has stopped answering his calls, and Cecilia has been missing for years. Not long after they were married, she vanished from his life and left him to raise their two young children alone. So who was Cecilia? Martin's eccentric wife, Gustav's enigmatic muse, an absent mother — a woman who was perhaps only true to herself. When Martin's daughter Rakel stumbles across a clue about what happened to her mother, she becomes determined to fill in the gaps in her family's story.

”Utterly gripping, like the films of Richard Linklater transmuted to the page. A magnificent doorstop of a novel.” —Guardian

>>Human existence of full of misery.

>>We don’t get endless opportunities.

>>Love, power, and art.

A History of Masculinity: From patriarchy to gender justice by Ivan Jablonka (translated from French by Nathan Bracher) $32

What does it mean to be a good man? To be a good father, or a good partner? A good brother, or a good friend? Jablonka offers a re-examination of the patriarchy and its impact on men. Ranging widely across cultures, from Mesopotamia to Confucianism to Christianity to the revolutions of the eighteenth century, Jablonka uncovers the origins of our patriarchal societies. He then offers an updated model of masculinity based on a theory of gender justice which aims for a redistribution of gender, just as social justice demands the redistribution of wealth. Arguing that it is high time for men to be as involved in gender justice as women, Jablonka shows that in order to build a more equal and respectful society, we must gain a deeper understanding of the structure of patriarchy — and reframe the conversation so that men define themselves by the rights of women.

The Hidden Fires: A Cairngorms journey with Nan Shepherd by Merryn Glover $40

Elemental, fierce and full of wonder, the Cairngorm mountains are the high and rocky heart of Scotland. To know them would take forever, to love them demands a kind of courageous surrender. In The Hidden Fires, Merryn Glover undertakes that challenge with Nan Shepherd as companion and guiding light. Following in the footsteps and contours of The Living Mountain, she explores the same landscapes and themes as Shepherd's seminal work. This is a journey separated by time but unified by space and purpose, a conversation between two women across nearly a century that explores how entering the life of a mountain can illuminate our own.

”A dazzling adventure into mountain, place and time. Redolent with the presence of Nan Shepherd, this book will captivate lovers of The Living Mountain.” —Esther Woolfson

>>The Living Mountain.

Porn: An oral history by Polly Barton $37

”Barton’s book carves out a space to hear a multitude of experiences, from interviewees of different genders and sexualities, who look at a range of porn from mainstream, queer, feminist or amateur. This kaleidoscopic approach allows us to understand many things about porn beyond if it is good or bad, empowering or exploitative, feminist or misogynistic. Activist or academic voices are the ones most commonly heard in conversations about porn. Barton instead gives the consumer a space to add their voices and knowledge to this ever-changing debate, and as a result they offer valuable and engaging insight into the everyday nature of porn consumption.'“ —Caroline West, Irish Independent

”I found my time with Porn: An Oral History unexpectedly moving. Barton’s candid, generous style as an interlocutor allows her subjects to move fluidly between their sometimes contradictory instincts and intellectual approaches in a way which feels revelatory and totally honest and human. A pleasure to read, and a vital new work for anyone interested in sex and its representation.” — Megan Nolan

”I wasn’t expecting nineteen conversations about porn to make me feel as I felt after reading this book: grateful and hopeful and wide-open. Porn is a generous, intimate commentary on how we relate to one another (or fail to) through the most unlikely of lenses.” — Saba Sams

”Porn is many things – a prompt for dreams, the outsourcing of fantasies, a heuristic for the construction of desire – but it is often omitted from our “spoken life”, to use Polly Barton’s wonderful phrase. In Porn, she manages to get people to talk about this subject both omnipresent and omnipresently swept under the rug, peeling off her informers’ ideological armour to get at what they really like and why, and invites us to ask, without forcing any answers, what it means for an entire society to possess an entire guilty conscience surrounding a genre now constitutive of our understanding of what sex is.” — Adrian Nathan West

>>The floodgates open.

>>Comfort level.

>>Read Thomas’s review of Fifty Sounds.

One of Them by Shaneel Lal $37

Growing up queer in a tiny, conservative village in Fiji, Shaneel Lal was subjected to beatings, torture and other horrific treatment from the elders and others, intended to drive the queerness from them or to stop it spreading to others(!). Escaping to Aotearoa, they were shocked to find that similar practices were legal here, and they became one of the inspiring voices in the ultimately successful campaign to outlaw so-called conversion therapy.

The Creative Act: A way of being by Rick Rubin $50

The legendary music producer has made a practice of helping people transcend their self-imposed expectations in order to reconnect with a state of innocence from which the surprising becomes inevitable. Over the years, as he has thought deeply about where creativity comes from and where it doesn't, he has learned that being an artist isn't about your specific output; it's about your relationship to the world.

”A gorgeous, delicious and wildly practical interrogation of the creative process. A master of his craft, Rubin supplies rich insights, sound advice, helpful suggestions and supreme comfort to anyone living to create, or endeavoring to live creatively.'“ —JJ Abrams

”This book is a companion to anyone on the creative path; for me, Rick Rubin's attention, consideration, ideas have dug themselves down deep into my consciousness and grown with my work, so that over time, I have found myself in the shelter of a huge resplendent tree, and remembered that it all started with a word or two from a person who really, really listened. May it start something similar in you.'“ — Kae Tempest

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

Sunday afternoon:

Thomas makes cinnamon buns from THE NORDIC BAKING BOOK by Magnus Nilsson.

This wonderful book contains recipes for many of the things I remember my Danish grandmother making (and me eating) when I was a child, but also hundreds of other cakes, breads, pastries and biscuits, with regional vartiations and Nilsson’s personable and illuminating commentary. We use the book frequently. On Sunday afternoon I made cinnamon buns, even though we still had cardamom cake (also from that book) left from Saturday.

Nilsson’s The Nordic Cookbook (which we also have) is similarly comprehensive, and provides insight into a wider swathe of Scandinavian food culture, with, again, hundreds of recipes and variations (and many more dishes from Farmor’s repertoire).

Read our 337th NEWSLETTER and find our what we’ve been reading and recommending, about our book of the week, and about several new books you will want for yourself.

7 July 2023

Tractatus Philosophico-Poeticus by Signe Gjessing (traslated from Danish by Denise Newman)

For some reason it had become a habit for him to write his reviews of books in the style of the books themselves, or as near a style as he could manage, a habit or an affectation, he wasn’t sure which, but this habit or affectation, if it was indeed a habit or an affectation, did have a serious intent, and was therefore not really a habit although it still could be an affectation, in that he somehow seemed to believe that a review written in the style of the subject of the review might reveal to him, and possibility to the readers of the review if there chanced to be any readers of the review, if such things could be left to chance, really such things were always left to chance, what was he saying, he seemed to believe that a review written in the style of the subject of the review might reveal something otherwise unnoticed or essential or incidental about the book in question, perhaps he was attempting to remove himself from a position of agency or of responsibility for the review by enticing, if that is the word, the book to write a review of itself. Form generates content, he shouted, frightening the cat, I want to write like a machine, I want to tinker with form until it purrs like a literary motor, then I will be able to put anything at all into the hopper, switch it on, and out comes literature. The cat was quick to resettle, she was used to this kind of excitement. If I were to write a review of Signe Gjessing’s Tractatus Philosophico-Poeticus in the form of Signe Gjessing’s Tractatus Philosophico-Poeticus I would also be writing it in the form of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, he thought, I would be writing it in the form of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus because Signe Gjessing has written her book in the form of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, in order, he thought, to see what kind of poetry could be generated by such a form, in order to use form as a machine for the generation of text, in order, he thought, to test the limits of language, to see what it is and is not good for, just like Wittgenstein, or just like Wittgenstein thought he was doing at the time he wrote that book. If Wittgenstein made no distinction between form and content, the same must be true of poetry, he thought. If for Wittgenstein the limits of knowledge are the limits of language, what are we to say of poetry, always straining as it does, or as it should, he thought or thought that perhaps he thought, into the unsayable? If Wittgenstein sought the limit of what can be said, through progressing out linguistically from the obvious towards that limit, pushing at it and establishing it, he thought, he entails that beyond that limit there exists not nothing but rather that about which nothing can be said. What cannot be said is signified by the complete exhaustion of that which can be said. Gjessing also is obsessed with the limit with which Wittgenstein was at the time he wrote his book obsessed, but she stands at that limit as if from the habitat beyond, both Wittgenstein and Gjessing are concerned to discover the nature of the limit inherent in language, if there is such a limit and such a limit is inherent, but Gjessing wants, he thought, to destroy that limit or even to show that the destruction of the limit inherent in language is itself inherent in language. He had written in his bad handwriting in his notebook that Gjessing had written in the introduction to her book that “The poem is a modification of the universal — as though the sayable were an incapacity of the unsayable,” and, he thought, Gjessing is running Wittgenstien’s machine in reverse to see what poetry comes out. If the world is comprised not of things but of states of affairs which are the grammatical relations between things, there is no reason to think that that which is not the case is not governed by or, he thought, even generated by this universal grammar. Texts are comprised not of words but of grammar, he shouted, but the cat was long gone. Well, he thought, if I was going to write my review of Signe Gjessing’s Tractatus Philosophico-Poeticus in the form of Signe Gjessing’s Tractatus Philosophico-Poeticus, I should have started earlier, I should have started, as does Gjessing, as does Wittgenstein to whose text Gjessing’s text is a response and a rejoinder, with a number of numbered statements on the first level to which another number of statements numbered to the first decimal respond or are implied and to which another number of statements numbered to the second decimal respond or are implied and so on until perhaps the fourth decimal or what we could call the fifth level, I’m not exactly sure if this is clear, a shining rack of cogs used in Wittgenstein’s case to generate philosophy, if he believed at that time there even was such a thing, and in Gjessing’s case to generate poetry, or whatever we might choose to call it, if I had written my review like this, he thought, what would I have written? Perhaps if I can devise such a grammatical machine to write reviews, a machine I can just turn upon any text, I can perhaps be relieved of certain of my duties, except perhaps to now and again apply a little oil, and perhaps get sometimes earlier to bed.

“3.01 The world is a good alternative to certainty.”

—Signe Gjessing, Tractatus Philiosphico-Poeticus

It seems that we have become dependent on photographs for our memories, for our identities, even for our authenticity. This fascinating novel explores what would happen if people started to become unrecordable by media, to disappear from photographs, to become gaps in a world in which image has become a substitute for actuality. The novel succeeds both because there is so much packed into it to think about (how we see, how we remember, the relationships between words and images, and the pictures we make in our heads of the fictional or of the actual) and because it is a superb portrayal of an ordinary life in a small town in Aotearoa and how that ordinary life is impacted as what we had thought of as reality begins to change in ways that we can neither control nor understand.

Ingredients at the ready for Louvana Me Marathos — budget conscious, with a delicious result!

TAVERNA: Recipes from a Cypriot kitchen by Georgina Hayden — reviewed by STELLA

I have a few Greek cookbooks, but this one I love the best. Partly, because it’s Cypriot cuisine and partly because I’ve become enamoured with several dishes from Taverna. The one that had me hooked straight away was the Louvana Me Marathos (yellow split pea and wild fennel soup) - so delicious and hearty, especially with a poached egg on top (vegan without). Perfect for any time of the year, and I can recommend it for a hearty winter supper, as well as refreshing summer fare. The lemon gives it zing, while the creamy texture of the split peas and rice is the ultimate comfort eating.

My father made the best keftedes — soft and flavoursome — so I’m always looking to replicate the texture (in my own pescatarian way). Georgina Hayden’s Fish Keftedes in Mustard and Dill are both delicate, creamy and indulgent — and flexible. You can swap out the fish type and adjust the quantity without any major repercussions, and the dill can be swapped for fennel. There are several keftedes recipes — three vegetable (including aubergine, of course) and pork. There are the slow-baked lamb and moussaka dishes which look just like my Yaya’s cooking right down to the enamel dishes, as well as the familiar traditional sweet pastries. In Taverna, Hayden draws on these favourites but also brings a contemporary twist to many of the dishes, making them lighter and less time-consuming to make. If you have apples, make the simple cake Milopita. Oranges? Portokalopita — a delicious sticky citrus wonder with shredded filo and yoghurt. But my favourites in this book remain tilted towards the savoury and everyday. Greek Cypriot cuisine is notable for its blend of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern influences, with plenty of fish and vegetarian choices. From simple fare to feasts, this is a cookbook to enjoy for its recipes as well as Georgina Hayden’s island and family stories.

New books — just out of the carton! Click through for your copies now.

Lioness by Emily Perkins $37

”You know how we say we devoured a story, and also that we were consumed by it? Eating and being eaten. It was like that with Claire, for me.” From humble beginnings, Therese has let herself grow used to a life of luxury after marrying into an empire-building family. But when rumours of corruption gather around her husband's latest development, the social opprobrium is shocking, the fallout swift, and Therese begins to look at her privileged and insular world with new eyes. In the flat below Therese, something else is brewing. Her neighbour Claire believes she's discovered the secret to living with freedom and authenticity, freeing herself from the mundanity of domesticity. Therese finds herself enchanted by the lure of the permissive zone Claire creates in her apartment a place of ecstatic release. All too quickly, Therese is forced to confront herself and her choices just how did she become this person? And what exactly should she do about it? The long-awaited novel (it has been eleven years since The Forrests!) from one of Aotearoa’s most notable writers.

>>Can a woman change her life?

>>A million unseen things.

Matariki by Gavin Bishop $16

When the Matariki cluster rises, each of the nine stars represent the promise of the year ahead. This stunning board book will guide our youngest tamariki through each star’s meaning, with simple, evocative words in te reo Māori and English, and with bold, engaging artwork. Mānawatia a Matariki! Happy Matariki!

>>Look inside!

The Pole, And other stories by J.M. Coetzee $40

Six stories exploring moral and emotional quandaries, often with wry humour. In the lead story, 'The Pole', set in Spain, concert pianist Witold attempts to play out a romantic fantasy with local music devotee Beatriz, who is considerably younger and whose marriage has gone cold. In person and in their correspondence, he is persistent, she resistant, but curious. It doesn't end quite as she might have imagined. The redoubtable character of Elizabeth Costello, now in her seventies, appears in four stories, engaging in philosophical discussions about death, motherhood and ethics with her adult children, in particular her son John. In the last story, 'The Dog', a young woman confronts a vicious dog- '"Curse you to hell!" she says. Then she mounts her bicycle and sets off up the hill.'

”To be hilarious about Heidegger is quite an achievement, but J.M. Coetzee pulls it off in one of these stories. Others, written in his beautifully limpid prose, raise profound questions about love, romantic and unromantic, growing old, and how we relate to animals. A marvellous collection that will delight and surprise you.” —Peter Singer

”Freed from literary convention, Mr Coetzee writes not to provide answers, but to ask great questions.” —Economist

The Skull: A Tyrolian folktale by Jon Klassen $36

In a big abandoned house, on a barren hill, lives a skull. A brave girl named Otilla has escaped from terrible danger and run away, and when she finds herself lost in the dark forest, the lonely house beckons. Her host, the skull, is afraid of something too, something that comes every night. Can brave Otilla save them both? Klassen’s artwork is better than ever, and the book is a beautifully produced hardback, with lovely paper stock.

>>Look inside (and see what the skull is frightened of)!

The Private Lives of Trees by Alejandro Zambra (translated by Megan McDowell) $25

Veronica is late, and Julian is increasingly convinced she won't ever come home. To pass the time, he improvises a story about trees to coax his stepdaughter, Daniela, to sleep. He has made a life as a literature professor, developing a novel about a man tending to a bonsai tree on the weekends. He is a narrator, an architect, a chronicler of other people's stories. But as the night stretches on before him, and the hours pass with no sign of Veronica, Julian finds himself caught up in the slipstream of the story of his life — of their lives together. What combination of desire and coincidence led them here, to this very night? What will the future — and possibly motherless — Daniela think of him and his stories? Why tell stories at all?

”When I read Zambra I feel like someone's shooting fireworks inside my head.” —Valeria Luiselli

>>Other books by Alejandro Zambra.

A Better Place by Stephen Daisley $38

In another visceral and involving novel, Daisley portrays the brutal effects of war on two New Zealand brothers. The old people in the district would often say that Roy was not quite the same after he come back. There was a brother. A twin brother, Tony. Tony Mitchell, different boy but a good rugby player. Bit of a mental case, they said, but Roy would have none of it. He always stayed close to Tony when they were growing up. They both went off to fight, must have been 1940. Only the one come back, though. Crete, they thought. We lost Tony over there.

”Stephen Daisley writes with the potent economy of a short-story writer, and he triumphs with this visceral account that will linger in your mind long after the last page.” —North & South

A Line in the World: A year on the North Sea coast by Dorthe Nors (translated from Danish by Caroline Waight) $40

There is a line that stretches from the northernmost tip of Denmark to where the Wadden Sea meets Holland in the south-west. Dorthe Nors, one of Denmark's most acclaimed contemporary writers, grew up on this line; a native Jutlander, her childhood was spent among the storm-battered trees and wind-blasted beaches of the North Sea coast. In A Line in the World, her first book of non-fiction, she recounts a lifetime spent in thrall to this coastline — both as a child, and as an adult returning to live in this mysterious, shifting landscape. This is the story of the violent collisions between the people who settled in these wild landscapes and the vagaries of the natural world. It is a story of storm surges and shipwrecks, sand dunes that engulf houses and power stations leaching chemicals into the water, of sun-creased mothers and children playing on shingle beaches. Nicely written.

"A beautiful, melancholy account of finding home on a restless coast. In Dorthe Nors's deft hands, the sea is no longer a negative space, but a character in its own right. I loved it." —Katherine May, author of Wintering

>>The shortest night of the year.

What an Owl Knows: The new science of the world’s most enigmatic birds by Jennifer Ackerman $40

For centuries, owls have captivated and intrigued us. Our fascination with these mysterious birds was first documented over 30,000 years ago, in the Chauvet cave paintings in southern France, and our enduring awareness and curiosity of their forward gaze and nearly silent flight has cemented the owl as a symbol of wisdom and knowledge, foresight and intuition. But what, really, does an owl know? Though our infatuation goes back centuries, scientists have only recently begun to study these birds in great detail. While more than 270 species exist today, and reside on every continent except Antarctica, owls are far more difficult to find and study than other birds - because while not only cryptic and perfectly camouflaged, owls are most active in the dark of night. Joining scientists on this maddening and elusive treasure hunt, Jennifer Ackerman brings alive the rich biological history of these animals and reveals the remarkable scientific discoveries into their brains and behaviour. She explores how, with modern technology and tools, researchers now know that owls talk all night long - without opening their bills. That their hoots follow a series of complex rules, allowing them to express needs and desires. That owls duet. They migrate. They use tools. They hoard their prey. Some live in underground burrows, some dine on scorpions. Ackerman brings this research alive with her own personal field observations about owls, and dives deep too into why this bird endlessly inspires and beguiles us.

>>What we can learn from owls.

The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt $37

Bob Comet is a retired librarian passing his solitary days surrounded by books in a mint-colored house in Portland, Oregon. One morning on his daily walk he encounters a confused elderly woman lost in a market and returns her to the senior center that is her home. Hoping to fill the void he's known since retiring, he begins volunteering at the center. Here, as a community of strange peers gathers around Bob, and following a happenstance brush with a painful complication from his past, the events of his life and the details of his character are revealed. Behind Bob Comet's straight man facade is the story of an unhappy child's runaway adventure during the last days of the Second World War, of true love won and stolen away, of the purpose and pride found in the librarian's vocation, and the pleasures of a life lived to the side of the masses.

>>(Unheroic).

I’d Rather Not by Robert Skinner $35

"I was sleeping in what might reasonably be described as a ditch, though I tried not to think of it in those terms for morale reasons." Robert Skinner arrives in the city, searching for a richer life. Things begin badly and then, surprisingly, get slightly worse. Pretty soon he’s sleeping rough and trying to run a literary magazine out of a dog park. His quest for meaning keeps being thwarted, by endless jobs, beagles, house parties, ill-advised love affairs, camel trips and bureaucratic entanglements. I’d Rather Not is about work, escape and that something more we all need.

”This book is like a big, properly made gin and tonic drunk outside in a garden on a perfect Saturday afternoon.” —Cate Kennedy

”No one writes better when the stakes are lower.” —Sam Vincent

>>Sunshine through the cracks in the wall.

Material World: A subtsantial story of our past and our future by Ed Conway $40

Sand, salt, iron, copper, oil and lithium. They built our world, and they will transform our future. These are the six most crucial substances in human history. They took us from the Dark Ages to the present day. They power our computers and phones, build our homes and offices, and create life-saving medicines. But most of us take them completely for granted. In Material World, Ed Conway travels the globe — from the sweltering depths of the deepest mine in Europe, to spotless silicon chip factories in Taiwan, to the eerie green pools where lithium originates — to uncover a secret world we rarely see. Revealing the true marvel of these substances, he follows the mind-boggling journeys, miraculous processes and little-known companies that turn the raw materials we all need into products of astonishing complexity. As we wrestle with climate change, energy crises and the threat of new global conflict, Conway shows why these substances matter more than ever before, and how the hidden battle to control them will shape our geopolitical future.

”Lively, rich and exciting, and full of surprises. Underlines that to understand global geopolitics, you need to understand natural resources and geology.” —Peter Frankopan

This Devastating Fever by Sophie Cunningham $28

Sometimes you need to delve into the past, to make sense of the present Alice had not expected to spend most of the twenty-first century writing about Leonard Woolf. When she stood on Morell Bridge watching fireworks explode from the rooftops of Melbourne at the start of a new millennium, she had only two thoughts. One was: the fireworks are better in Sydney. The other was: is Y2K going to be a thing? Y2K was not a thing. But there were worse disasters to come. Environmental collapse. The return of fascism. Wars. A sexual reckoning. A plague. Uncertain of what to do she picks up an unfinished project and finds herself trapped with the ghosts of writers past. What began as a novel about a member of the Bloomsbury Set, colonial administrator, publisher and husband of one the most famous English writers of the last hundred years becomes something else altogether. Now in paperback.

”This Devastating Fever is thrillingly audacious fiction. Sophie Cunningham’s entwined subjects are profound — Leonard Woolf and colonialism, the crises of the present day, the challenges of creative work — and she writes commandingly and inventively about them all. The result is an extraordinary novel.” —Michelle de Kretser

'This is a great novel of enduring significance and enormous beauty.’ – Sydney Morning Herald

>>Click!

>>Grace in the trying.

Horizons: A global history of science by James Poskett $32

A radical retelling of the history of science that foregrounds the scientists erased from history. In this major retelling of the history of science from 1450 to the present day, James Poskett explodes the myth that science began in Europe. The blinkered Western gaze focusing on individual 'genius' — Copernicus, Newton, Darwin, Einstein - was only one part of the story. The reality was an utterly global, non-linear pattern of cross-fertilisation, competition, cooperation and outright conflict. Each rupture in history carved fresh channels for global exchange. Here, for the first time, Poskett celebrates how scientists from Africa, America, Asia and the Pacific were integral to this very human story. We meet Graman Kwasi, the African botanist who discovered a new cure for malaria; Hantaro Nagaoka, the Japanese scientist who first described the structure of the atom; and Zhao Zhongyao, the Chinese physicist who discovered antimatter. Now in paperback.

The Bear House by Meaghan McIsaac $24

Moody Aster and her spoiled sister Ursula are the daughters of Jasper Lourdes, Bear Major and high king of the realm. Rivals, both girls dream of becoming the Bear queen someday, although neither really deserve to, having no particular talent in... well, anything. But when their Uncle Bram murders their father in a bid for the crown, the girls are forced onto the run, along with lowly Dev the Bearkeeper and the half-grown grizzly Alcor, symbol of their house. As a bitter struggle for the throne consumes the kingdom in civil war, the sisters must rely on Dev, the bear cub, and each other to survive — and find wells of courage, cunning, and skill they never knew they had.

Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks $37

Yamaye lives for the weekend, when she can go raving with her friends at The Crypt, an underground club in the industrial town on the outskirts of London where she was born and raised. A young woman unsure of her future, the sound is her guide — a chance to discover who she really is in the rhythms of those smoke-filled nights. In the dance-hall darkness, dub is the music of her soul, her friendships, her ancestry. But everything changes when she meets Moose, the man she falls deeply in love with, and who offers her the chance of freedom and escape. When their relationship is brutally cut short, Yamaye goes on a dramatic journey of transformation that takes her first to Bristol — where she is caught up in a criminal gang and the police riots sweeping the country — and then to Jamaica, where past and present collide with explosive consequences.

Short-listed for the 2023 Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Event Factory by Renée Gladman $38

A ‘linguist-traveler’ arrives by plane to Ravicka, a city of yellow air in which an undefined crisis is causing the inhabitants to flee. Although fluent in the native language, she quickly finds herself on the outside of every experience. Things happen to her, events transpire, but it is as if the city itself, the performance of life there, eludes her. Setting out to uncover the source of the city's erosion, she is beset by this other crisis—an ontological crisis—as she struggles to retain a sense of what is happening. Gladman’s novels about the invented city-state of Ravicka, a foreign ‘other’ place are fraught with the crises of contemporary urban experience, not least the fundamental problem of how to move through the world at all.

”More Kafka than Kafka, Renee Gladman's achievement ranks alongside many of Borges' in its creation of a fantastical landscape with deep psychological impact." —Jeff VanderMeer

"In Renee Gladman's extraordinary Event Factory, the world in all its languaged variousness adumbrates a 'yellow-becoming' map for our deepest internal spelunkings, a map we don't dare do without as we negotiate, along with our intrepid narrator, the world of Ravicka, the sprawling city, where, we might say, to borrow from Gladman, 'nothing happens, nothing happens, then everything is 'said' to happen . . .' and where we might also say, to borrow from Beckett, the magnifying and minifying mirrors have been shattered and the body has, yes, 'vanished in the havoc of its images.'" —Laird Hunt

"Gladman is more fantasist than estranging analyst. The quality of her dreaming, its interior abstraction, is exquisite. Its wonder lies in how closed its shutters are to any mundane world, how far back the lanes and alleyways of its imagining recede from the proper nouns and pedestrianisms of our lives." —n+1

"The Ravikian novels exalt the primacy of language to further imaginative possibility, which dominant and oppressive regimes would shut down. Gladman's writing cleaves to the luminous. It slips through the gaps in our thinking to pluralise, queer, subvert, and mobilise. These books are strange but, through a bright and deft poetic obliquity, they shine an incomparable light onto our contemporary moment." —The White Review

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

Read our 336th NEWSLETTER and find our what we’ve been reading and recommending — and what you will soon be reading and recommending.

30 June 2023

Extinction by Thomas Bernhard (translated by David McLintock) {reviewed by Thomas}

“When I take Wolfsegg and my family apart, when I dissect, annihilate and extinguish them, I am actually taking myself apart, dissecting, annihilating and extinguishing myself. I have to admit that this idea of self-dissection and self-annihilation appeals to me, I told Gambetti. I’ll spend my life dissecting and extinguishing myself, Gambetti, and if I’m not mistaken I’ll succeed in this self-dissection and self-extinction. I actually do nothing but dissect and extinguish myself.” In the first of the two relentless paragraphs that comprise this wonderfully claustrophobic novel, the narrator, Murau, has received a telegram informing him that his parents and brother have been killed in a car accident. While looking at some photographs of them at his desk in Rome, he unleashes a 150-page stream of invective directed personally at the members of his family, both dead and living. Murau is alone, but he addresses his rant to his student Gambetti in Gambetti’s absence or recounts, however accurately or inaccurately, addressing Gambetti in person at some earlier time. Gambetti, in either case, is completely passive and non-contributive, and this passivity and non-contribution acts — along with Murau’s over-identification with his ‘black sheep’ Uncle Georg, an over-identification that sometimes confuses their identities — as a catalyst for Murau’s invective, as an anchor for the over-inflation of Murau’s hatred for, and difference from, his family. Without external contributions that might mitigate Murau’s opinions, his family appear as horrendous grotesques, exaggerations that here cannot be contradicted due to absence or death. Being dead puts an end to your contributions to the ideas people have of you: stories concerning you are henceforth the domain entirely of others and soon become largely expressions of their failings, impulses and inclinations. We can have no definite idea of ourselves, though: we exist only to others, unavoidably as misrepresentations, as caricatures. Murau states that he intends to write a book, to be titled Extinction: “The sole purpose of my account will be to extinguish what it describes, to extinguish anything that Wolfsegg means to me, everything that Wolfsegg is, everything. My work will be nothing other than an act of extinction.” Murau has not been able to even begin to write this account because his hatred gets in the way of beginning, or, rather, what we soon suspect to be the inauthenticity of his hatred gets in the way of beginning. There is no loathing without self-loathing. As Murau’s invective demonstrates, there can be no statement that is not an overstatement: every statement tends towards exaggeration as soon as it is expressed or thought. By exaggeration a statement exhausts its veracity and immediately begins to incline towards its opposite, just as every impulse, as soon as it is expressed, inclines towards its opposite. Only a passive witness, a witness who does not contradict but, by witnessing, in effect affirms, Gambetti in Murau’s case, allows an otherwise unsustainable idea to be sustained. In the second half of the book, Murau returns to Wolfsegg in Austria for the funeral of his parents and brother. Until this point, Murau’s ‘character’ has been defined entirely by his exaggerated opposition to, or identification with, his ideas of others, but when he is brought into situations in which others have a contributing role, Murau’s portrayal of others and of himself in the first section is undermined at every turn. Without the ‘Gambetti’ prop, he is responded to, and, in response to these responses, he overturns many of his opinions — about his parents, his brothers, his sisters, his mother’s lover, the nauseatingly perfectly false Spadolini that Murau had hitherto admired, and about himself - and reveals his fundamental ambivalence, an ambivalence that is fundamental to all existence but which is usually, for most of us, almost entirely suppressed by praxis, by the passive anchors, the Gambettis to which we affix our desperate attempts at character. We resist — through exaggeration — indifference and self-nullification. “We’re often led to exaggerate, I said later, to such an extent that we take our exaggeration to be the only logical fact, with the result that we don’t perceive the real facts at all, only the monstrous exaggeration. I’ve always found gratification in my fanatical faith in exaggeration, I told Gambetti. On occasion I transform this fanatical faith in exaggeration into an art, when it offers the only way out of my mental misery, my spiritual malaise. Exaggeration is the secret of great art, I said, and of great philosophy. The art of exaggeration is in fact the secret of all mental endeavour.” In this second part, Murau reveals his connection with Wolfsegg and his suppressed feelings of culpability in what it represents. “I had not in fact freed myself from Wolfsegg and made myself independent but maimed myself quite alarmingly.” Separation, or, rather, the illusion of separation, is only achieved by ‘art’, that is to say, by exaggeration, by the denial of ambivalence, by the denial of complicity, by suppression: a desperate negative act of self-invention. Once his hatred of his sisters, and of his parents and brothers, has been undermined by his presence and contact with others at Wolfsegg, and without a Gambetti or Georg in his mind to sustain this hatred, the underlying reason for his hatred, a fact that he has suppressed since his childhood as too uncomfortable, the fact that has made “a gaping void” of his childhood, of his whole past, the fact to which he was a passive witness, a complicit witness, namely that Wolfsegg hid and sheltered Nazi war criminals after the war (Gauleiters and members of the Blood Order, who now attend the funeral of Murau’s father) in the so-called ‘Children’s Villa’ (which “affords the most brutal evidence that childhood is no longer possible. All you see when you look back is this gaping void. You actually believed that your childhood could be repainted and redecorated, as it were, that it could be refurbished and reroofed like the Children’s Villa, and this in spite of hundreds of failed attempts at restoring your childhood.”), can now be faced, and, on the final page of the book, at last in some way addressed. Murau also attains the necessary degree of remove to write Extinction before his own death, either from illness or, more likely, suicide. This, his last, is the only Bernhard novel I can think of in which the protagonist makes anything that resembles an effective resolution.

>>Your copy.

The legacies of French colonial history and the resulting fractures in Parisian society, along with the conformism and competitiveness of last-stage Capitalism are explored with great verve and humour in this sharply satirical novel in which an Ivorian immigrant working as a security guard in a department store observes the impact of vast social pressures on the miniscule particulars of everyday life. GauZ’’s supple text is filled with recognisable observations on the ‘human condition’ (so to call it), and also provides a context and texture that helps us to understand the current unrest in France.

The Words for Her by Thomasin Sleigh — reviewed by Stella

They are there, but they are not. They are ‘gone’. They are gaps. Gaps in the photographs. Unseen by your phone. They have changed. Think this sounds surreal? It’s compelling. If you are going to read one novel this year, make it this one. The Words for Her is a master class in blending intriguing and intelligent ideas about images and words with the realist grit of surviving as a solo parent in a small provincial town; complete with a twist of dystopia and societal collapse. The collapse, a chaotic slow-motion act, is triggered by people disappearing; that is, their images disappearing. No longer uploadable, missing from their social media profiles, leaving gaps in family photographs, no longer present — no record — at social gatherings. This is a story of a mother protecting her daughter, of the power of words to create a picture, and of the intense relationship we have with the recorded, particularly digital, image. Out-sourcing our memory is possibly the crime of our times. How many times a day do we reach for our phone? How many photos do you have stored in the cloud or on file of family, friends, or yourself? How entrenched are we in the idea of who we are through the images of ourselves? If you couldn’t record yourself or your loved ones, would you feel bereft? In The Words for Her, Jodie is uneasy. She senses something lurking within her, playing at the corners of her mind. But is it a terrible thing? That she has a gift for description has helped more than one person in her life. For her friend, Miri, it released her from a bad relationship; disappearing gave her the opportunity for a new life. For her blind father, Jodie’s ‘colouring’ brings the world to life through intricate wordplay. This is so clever to read in a work of literature. For this is what reading does — creates images where we can wander. Jodie will protect Jade, her daughter, even if it means 'going out'. But can she? As danger lurks closer, someone knows what she can do, this mother has to make a choice from which there may be no return. The first time they notice a gap is while watching the news — the presenter fades away, her hands gripping the edge of the desk until they too go. The camera pans away. At first, it is strangers, then people related to someone you know, then celebrities, and then it will be someone close to you. As more people go 'out', the division between the Gaps and the Presents beds in. If you are 'present', you feel compelled to prove it. Billboards go up everywhere with smiling ‘present’ people. The Gaps seek out their own kind as they are shut out of society. There’s a shame to being 'gone', and practical problems. No longer scannable. No image on your driver’s license. Your newborn is ‘invisible’. Thomasin Sleigh brings us a wealth of ideas — even as you are carried impulsively and enjoyably forward with the plot — which are intriguing, complex (yet not inaccessible), and thought-provoking. This is my favourite kind of novel, one which layers ideas and story-telling where both the quotidian and the speculative edge against each other to reveal our present with a fresh, intelligent perspective.

>>Your copy.

New books — just out of the carton! Click through for your copies now.

Bibliolepsy by Gina Apostol $37

It is the mid-eighties, two decades into the kleptocratic, brutal rule of Ferdinand Marcos. The Philippine economy is in deep recession, and civil unrest is growing by the day. But Primi Peregrino has her own priorities: tracking down books and pursuing romantic connections with their authors. For Primi, the nascent revolution means that writers are gathering more often, and with greater urgency, so that every poetry reading she attends presents a veritable ‘Justice League’ of authors for her to choose among. As the Marcos dictatorship stands poised to topple, Primi remains true to her fantasy: that she, "a vagabond from history, a runaway from time," can be saved by sex, love, and books.

"Bibliolepsy, despite all the couplings and uncouplings, is not a love story, or at least not a typical love story involving a man or a woman. It is, as the title implies, about an obsessive, overpowering love of books. For those of us who have gotten down on our hands and knees to thoroughly search bargain book bins, we will find our fervor echoed in the character of pale, biblioleptic Primi, and find Bibliolepsy dizzyingly eloquent, slightly disturbing, but ultimately strangely comforting." —Luis Katigbak, The Philippine Star

>>We never see ourselves as others see us.

Home Reading Service by Fabio Morábito (translated by Curtis Bauer) $26

After a traffic accident, Eduardo is sentenced to a year of community service reading to the elderly and disabled. Stripped of his driver's licence and feeling impotent as he nears thirty-five, he leads a dull, lonely life, chatting occasionally with the waitresses of a local restaurant or walking the streets of Cuernavaca. Once a quiet town known for its lush gardens and swimming pools, the ‘City of Eternal Spring’ is now plagued by robberies, kidnappings, and the other myriad forms of violence bred by drug trafficking. At first, Eduardo seems unable to connect. He movingly reads the words of Dostoyevsky, Henry James, Daphne du Maurier, and more, but doesn't truly understand them. His eccentric listeners — including two brothers, one mute, who moves his lips while the other acts as ventriloquist; deaf parents raising children they don't know are hearing; and a beautiful, wheelchair-bound mezzo soprano — sense his detachment. Then Eduardo comes across a poem his father had copied by the Mexican poet Isabel Fraire, and it affects him as no literature has before. Through these fascinating characters, like the practical, quick-witted Celeste, who intuitively grasps poetry even though she never learned to read, Morabito shows how art can help us rediscover meaning in a corrupt, unequal society.

"First, the tempting promise of an almost existential discovery, then bewilderment, subtle humor, and then everything in this story that seemed small and simple strikes back with extraordinary resonance. What a pleasure it always is to read Morabito." —Samanta Schweblin

>>Poetry can be dangerous.

Granta 162: Definitive narratives of escape $33

Raymond Antrobus on performer Johnnie Ray, Marina Benjamin on playing professional blackjack, Chanelle Benz on searching for a homeland, Annie Ernaux (tr. Alison L. Strayer) on what affairs can help us bear, Richard Eyre on his grandfathers, Des Fitzgerald on losing his brother, Caspar Henderson on the sounds in space, Amitava Kumar on India today, Emily LaBarge on PTSD, Michael Moritz on antisemitism in Wales, TaraShea Nesbit on coping with a miscarriage, Roger Reeves on visiting a former site of slavery, Xiao Yue Shan on Iceland. Fiction by Carlos Fonseca (tr. Megan McDowell), Maylis de Kerangal (tr. Jessica Moore) and Catherine Lacey; photography by Kalpesh Lathigra; in conversation with Granta, Cian Oba-Smith, introduced by Gary Younge, and Aaron Schuman, introduced by Sigrid Rausing. Plus a poem by Peter Gizzi.

Hit Parade of Tears by Izumi Suzuki $25

Izumi Suzuki had ideas of how things might be done differently, ideas that paid little heed to the laws of physics, or the laws of the courts. In this new collection her skewed imagination is applied to some classic science fiction and fantasy tropes. A philandering husbands receives a bestial punishment from a wife who'd kept her own secrets; time-travelling pop music aficionados stir up temporal bother when their nostalgia carries them away; idle high school students find themselves dropped into a adventure in another dimension, but aren't all that impressed; a misfit band of space pirates discover a mysterious baby among the stars; Emma, the Bovary-like character from Terminal Boredom's 'Forgotten', lands herself in another bizarre romantic pickle. From the author of Terminal Boredom.

>>Twisted precision.

>>A writer from the future.

>>Punk rock sci-fi.

They Call It Love: The politics of emotional life by Alva Gotby $40

Comforting a family member or friend, soothing children, providing company for the elderly, ensuring that people feel well enough to work; this is all essential labour. Without it, capitalism would cease to function. They Call It Love investigates the work that makes a haven in a heartless world, examining who performs this labour, how it is organised, and how it might change. Gotby calls this work ‘emotional reproduction’, unveiling its inherently political nature. It not only ensures people's well-being but creates sentimental attachments to social hierarchy and the status quo. Drawing on the thought of the feminist movement Wages for Housework, Gotby demonstrates that emotion is a key element of capitalist reproduction. To improve the way we relate to one another will require a radical restructuring of society.

>>How do you know you are loved?

Scream (‘Object Lessons’ series) by Michael J. Seidlinger $23

When you are born, the first thing you do is scream. Be it a response to fear, anger, sadness, or happiness, the scream is a declaration of being alive. The metal vocalist cupping the microphone blares out a deafeningly harsh scream. The drill instructor screams out commands to their soldiers. And then there's the bloodcurdling screams we know from horror films. A scream has many meanings, but it is an instinctive and reflexive action that, at its core, reveals raw emotion.Investigating popular and alternative cultures, art, and science, Michael J. Seidlinger tracks the resonance of the scream across media and literature and in his own voice.

>>Other ‘Object Lessons’.

The Gospel of Orla by Eoghan Walls $37

The Gospel of Orla is the coming-of-age story of a young girl, Orla, and the man she meets who has an astonishing and unique ability. It is also a road novel that takes us across the north of England after the two flee Orla's village together. Here the mysteries of faith charge full bore into the vagaries of contemporary mores. A humorous, wise, deeply human and sometimes breathtaking work of lyrical fiction.

"The Gospel of Orla is written with immense control and precision so that the voice of the protagonist emerges as alive, individual and memorable. Eoghan Walls manages to make every single emotion Orla feels — every thought, response and action — utterly convincing and fresh and original." —Colm Toibin

Jena, 1800: The Republic of Free Spirits by Peter Neumann (translated by Shelley Frisch) $40

At the turn of the nineteenth century, a steady stream of young German poets and thinkers coursed to the town of Jena to make history. In the wake of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, confidence in traditional social, political, and religious norms had been replaced by a profound uncertainty that was as terrifying for some as it was exhilarating for others. Nowhere was the excitement more palpable than among the extraordinary group of poets, philosophers, translators, and socialites who gathered in Jena. This village of just four thousand residents soon became the place to be for the young and intellectually curious in search of philosophical disruption. Influenced by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, then an elder statesman and artistic eminence, the leading figures among the disruptors — the translator August Wilhelm Schlegel; the philosophers Friedrich Schlegel and Friedrich Schelling; the dazzling, controversial intellectual Caroline Schlegel, married to August; the poet and translator Dorothea Schlegel, married to Friedrich; and the poets Ludwig Tieck and Novalis — resolved to rethink the world, to establish a republic of free spirits. They didn't just question inherited societal traditions; with their provocative views of the individual and of nature, they revolutionised our understanding of freedom and reality.

The Jaguar by Sarah Holland-Batt $30

Sarah Holland-Batt confronts what it means to be mortal in an astonishing and humane portrait of a father's Parkinson's Disease, and a daughter forged by grief. Opening and closing with elegies set in the charged moments before and after a death, and compulsively probing the body's animal endurance and appetites, along with the metamorphoses of long illness, The Jaguar is marked by Holland-Batt's distinctive lyric intensity and linguistic mastery, along with a stark new clarity of voice. In this collection Holland-Batt is at her most exacting and uncompromising — these ferociously intelligent, insistent poems refuse to look away, and challenge us to view ruthless witness as a form of love.

Winner of the 2023 Stella Prize.

‘A Bloody Difficult Subject’: Ruth Ross, te Tiriti o Waitangi, and the making of history by Bain Attwood $60

Ruth Ross is hardly a household name, yet most New Zealanders today owe the way they understand the Treaty of Waitangi — or te Tiriti o Waitangi as Ross called it — to this remarkable woman’s path-breaking historical research. Taking us on a journey from small university classes and a lively government department in the nation’s war-time capital to an economically poor but culturally rich Māori community in the far north, and from tiny schools and cloistered university offices to parliamentary committees and a legal tribunal, Attwood enables us to grasp how and why the place of the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand law, politics, society and culture has been transformed in the last seven decades. A frank and moving meditation on the making of history and its advantages and disadvantages for life in a democratic society, A Bloody Difficult Subject is a surprising story full of unforeseen circumstances, unexpected twists, unlikely turns and unanticipated outcomes.

Malta: Mediterranean recipes from the islands by Simon Bajada $50

Over 65 recipes from the archipelago between Italy and the North African coast. Exploring his own family heritage, author Simon Bajada captures Maltese food for the home cook, with recipes including ftira, a sourdough bread drenched in tomato, tuna and olives; aljotta soup, a flavour-packed brew of fish and garlic; and pastizzi, a deliciously addictive pastry.

>>Look inside!

Pregnancy Test (‘Object Lessons’ series) by Karen Weingarten $23

In the 1970s, the invention of the home pregnancy test changed what it means to be pregnant. For the first time, women could use a technology in the privacy of their own homes that gave them a yes or no answer. That answer had the power to change the course of their reproductive lives, and it chipped away at a paternalistic culture that gave gynecologists-the majority of whom were men-control over information about women's bodies.However, while science so often promises clear-cut answers, the reality of pregnancy is often much messier. Pregnancy Test explores how the pregnancy test has not always lived up to the fantasy that more information equals more knowledge. Karen Weingarten examines the history and cultural representation of the pregnancy test to show how this object radically changed sex and pregnancy in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

>>Other ‘Object Lessons’.

My Pen Is the Wing of a Bird: New fiction by Afghan women edited by Lyse Doucet and Lucy Hannah $28

"My pen is the wing of a bird; it will tell you those thoughts we are not allowed to think, those dreams we are not allowed to dream." A woman's fortitude saves her village from disaster. A teenager explores their identity in a moment of quiet. A petition writer reflects on his life as a dog lies nursing her puppies. A tormented girl tries to find love through a horrific act. A headmaster makes his way to work, treading the fine line between life and death. My Pen Is the Wing of a Bird is a landmark collection: the first anthology of short fiction by Afghan women. Eighteen writers — from the country’s two main linguistic groups Pashto and Dari — tell stories that are both unique and universal — stories of family, work, childhood, friendship, war, gender identity and cultural traditions.

"This book reminds us that everyone has a story. Stories matter; so too the storytellers. Afghan women writers, informed and inspired by their own personal experiences, are best placed to bring us these powerful insights into the lives of Afghans and, most of all, the lives of women. Women's lives, in their own words — they matter." —Lyse Doucet

Into the Forest: A Holocaust story of survival, triumph, and love by Rebecca Frankel $40

In the summer of 1942, the Rabinowitz family narrowly escaped the Nazi ghetto in their Polish town by fleeing to the forbidding Bialowieza Forest. They miraculously survived two years in the woods — through brutal winters, Typhus outbreaks, and merciless Nazi raids — until they were liberated by the Red Army in 1944. After the war they trekked across the Alps into Italy where they settled as refugees before eventually immigrating to the United States. During the first ghetto massacre, Miriam Rabinowitz rescued a young boy named Philip by pretending he was her son. Nearly a decade later, a chance encounter at a wedding in Brooklyn would lead Philip to find the woman who saved him — and to discover her daughter Ruth was the love of his life.

The Forevers by Cjris Whitaker $20

They knew the end was coming. They saw it ten years back, when it was far enough away in space and time and meaning. The changes were gradual, and then sudden. For Mae and her friends, it means navigating a life where action and consequence are no longer related. Where the popular are both trophies and targets. And where petty grudges turn deadlier with each passing day. So, did Abi Manton jump off the cliff or was she pushed? Her death is just the beginning of the end. With teachers losing control of their students and themselves, and the end rushing toward all of them, it leaves everyone facing the answer to one, simple question... What would you do if you could get away with anything? A gripping YA novel.

The Germ Lab: The grusome story of deadly diseases by Richard Platt and John Kelly $23