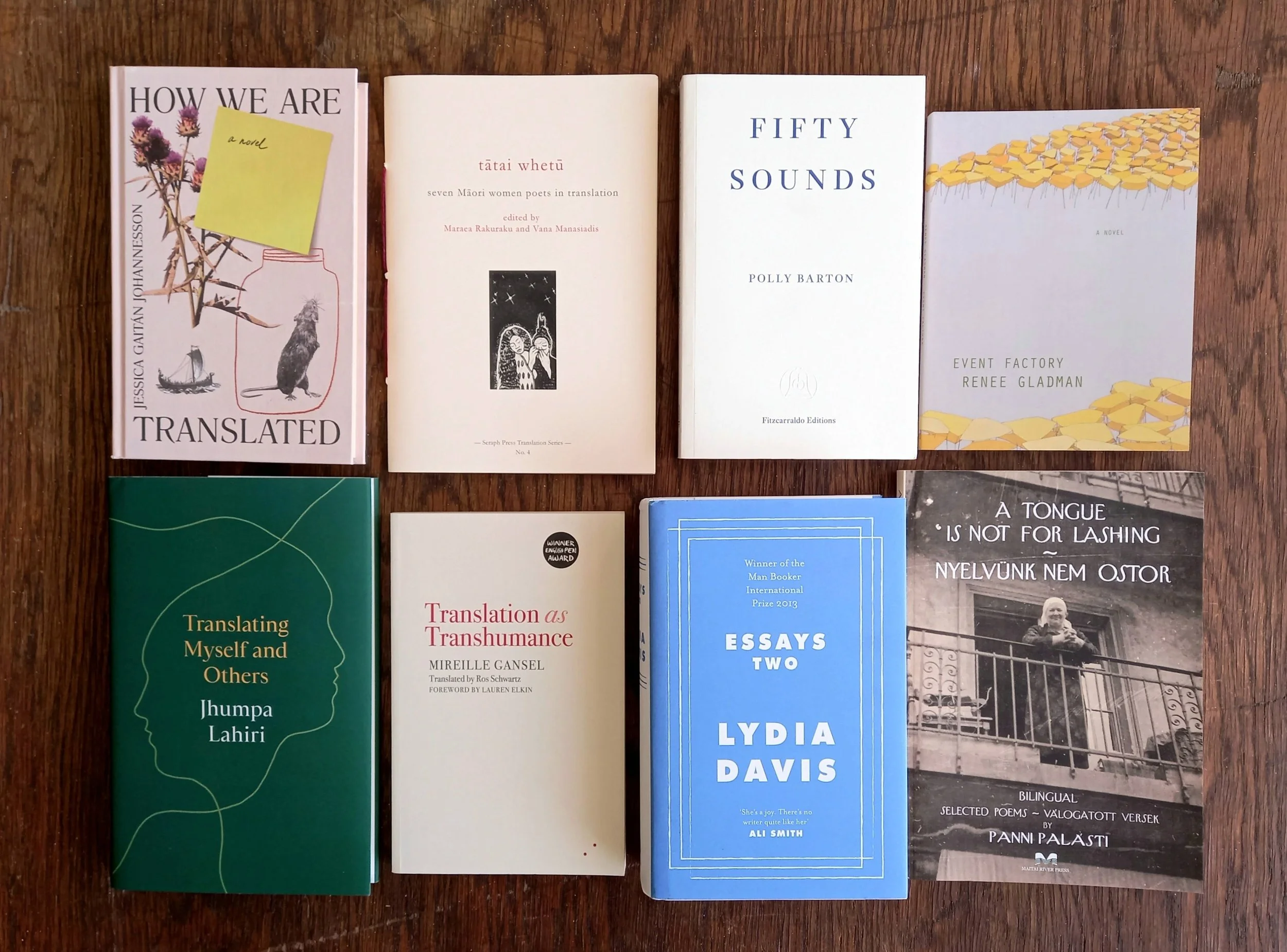

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Celebrate Women in Translation Month!

Browse our translated fiction here.

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Celebrate Women in Translation Month!

Browse our translated fiction here.

Read our #341st NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending — and about our short, sharp history sale.

4 August 2023

Wall by Jen Craig

She has come back to Australia to clear out her father’s house following his death. Her father was a hoarder so his house is very full. Of many sorts of things. Some of the contents are decaying. Some of the contents are carefully ordered. Others not ordered at all. Carefully disordered, even, if this is possible. This is what remains of her father; her memories of him cannot be untangled from the foibles she now perceives in herself. They are not dissimilar. Or were not dissimilar. Being similar. She thinks of herself as an artist; that is to say, she is therefore an artist, and others also think of her as an artist. Her art doesn’t sound particularly good, but it takes up a lot of her time. Which is something. I suppose she makes art in which other people can perceive the qualities that they look for in art, not that these are related to the qualities she herself perceives in her art, particularly, not that it matters. She is most well-known, not that she is well-known, for a three-person piece of student performance art about their anorexia, a piece that was misperceived, or rather misdetermined, if there is such a word, by others, who assumed conceptual dominion, if that is not too strong a word, over it, which, I suppose, is the anorectic predicament. The person who most misdetermined the work was their tutor, her one-time and seemingly enduring art mentor, so to call him, now a gallerist, whom she badly wants to impress or make use of, which is the same thing, despite his dubious qualities and ludicrous name, or because of them. She wants to make another work, her own work, about anorexia, and to call it ‘Wall’, a work this time determined by her, but she doesn’t know how to do this; perhaps this is impossible, perhaps a self-determined work could never say anything much about anorexia. Anyway, she has come back to Australia and had the idea of making the entire contents of her father’s house into an artwork, not the anorectic artwork, transporting, sorting and displaying it in a gallery. This has been done before, however, so it is not exactly a new idea. Also, she doesn’t have the time or the energy or the stickability to achieve it, and, in any case, it is not as if the contents of her father’s house say in themselves much about her father; rather it is the way that they are packed into the house, some of the contents carefully ordered, others not ordered at all, carefully disordered, even, if such a thing is possible, that comprise the person that was her father. And, of course, she is not dissimilar, or is similar, herself. It is not her thoughts, of which the words in this book are a fair example, that comprise her; many of these thoughts are thoughts that come to her from others, who knows where thoughts come from, detritus and happenstance; it is the bundling of the thoughts, the way they are arranged, their syntactical relationships, that comprise a person. Not that she can perceive herself as a person; she can only be perceived by others. She exists, if that is not too strong a word, only in the ideas had of her by others, as do we all, and the ideas had by others are seldom anything but misperceptions or, rather, misdeterminations, if there is such a word, or, even better, mispresumptions, there is surely no such word, at least until now, which brings us back to the anorectic predicament: what, if anything, of ourselves is not determined by others? Without the ideas that others have of her, we know, she can barely be said to exist. The words we read have ostensibly been written by her to someone, presumably her partner, back in London, and this determining ‘you’ both dominates the text and the form of her existence, so to call it, the bundling of her thoughts, therein, and is as well the mesh against which she can push herself and see what, if anything, and maybe there’s something, gets through. She has come back to Australia to clear out her father’s house. As soon as she arrives there it is obvious to her that she will never make the intended “post-war manifestation of twenty-first century anxiety on a suburban Australian scale” based on Song Dong’s famous artwork; she immediately orders a skip and begins to throw the contents of the hallway onto the lawn. By the end of the book she has only begun to enter and to clear out her father’s house; she has only begun to enter and to clear out the contents of her mind, so to call it, so bound up as it is with the foundational idea of her father, she is a hoarder just like him, a mental hoarder, and to throw the contents out onto the lawn in preparation for the skip, both the objects and the thoughts, if I can force the metaphor, not that this is a metaphor. All accumulations, things crammed into houses, thoughts crammed into minds, function in similar ways, are hoarded and dispersed in similar ways, are susceptible in similar ways to our sifting and sorting and also to our failure or refusal to sift and to sort. Jen Craig’s syntactically superb sentences are the best possible intimations of the ways in which thoughts remain stubbornly embedded in their aggregate when we attempt to bring them into the light.

>>Your copy.

This is the week you can add some excellent history books to your shelves. Unlock history with these recommendations. Interested in textiles and the history of clothing, then you need Worn which is an excellent blend of history and social commentary, complete with wonderful information about those five fibre staples; cotton, wool, synthetics, silk and linen. If are intrigued by Japan and enjoy women's histories you can't go past the excellent Stranger in the Shogun's City which is fascinating and superbly written. Other women's histories that are must haves are Svetlana Alexievich's The Unwomanly Face of War and Barbara Brookes's A History of New Zealand Women. For an excellent social history centred on food, Claudia Roden's The Book of Jewish Food is packed with insightful information (and recipes) and will distract you from your cooking. More intrigued by the machinations of Eastern Europe then there's Philippe Sands's brilliant East West Street. Looking for something different, there's the stunning Te Ahi Ka, the fascinating A History of Bombing, and the moving Library of Exile.

Use the key HIST101 when checking out for a 15% discount on all history books. (Promotion ends 13 August 2023. (In-stock items only; excludes items already marked down.) >>Click through to start choosing now.

Our Book of the Week is the completely delightful (and developmentally valuable) LOOK by Gavin Bishop. Presented as a two-metre long two-sided concertina board book, Look can be opened out to surround a baby during ‘tummy time’ (building motor skills and strength), or shared as a book (building concepts and affectionate ‘conversations’). The simple and very appealing illustrations show faces for one direction/side, and toys and other familiar objects for the other. This will immediately become one of those special books that are central to a baby’s (and a parent’s) life.

Other wonderful board books by Gavin Bishop: Friend / E Hoa ; Koro / Pops ; Mihi ; Matariki.

Large-format, lively, beautifully illustrated books packed with information for older children (and adults). Every home needs these: Aotearoa: The New Zealand Story ; Wildlife of Aotearoa ; Atua: Māori Gods and Heroes.

Get LOOK now (by the way: we can send books anywhere (gift-wrapped, if you like!)).

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Read our #340th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending.

28 July 2023

A Million Windows by Gerald Murnane — reviewed by Thomas

The great concern in Murnane’s writing is the relationship between the fiction he writes and what he calls the ‘image world’ (he insists this is nothing to do with ‘imagination’ in the sense of making things up (he is, he says, incapable of making things up)), and, to a lesser yet strongly implied degree, the relationship between these two and the ‘actual world’, which he seems to regard as little more than an access point to (or of) the image world, and a place of frailties, disappointment and impermanent concerns. When Murnane describes the “chief character of a conjectured piece of fiction… a certain fictional male personage, a young man and hardly more than a boy” preferring the image-world relationship he had inside his head with a “certain young woman, hardly more than a girl” he sees every day in the railway carriage in which he travels home from school to the actual relationship he starts to develop (and soon abandons) with her after they eventually start to converse, he underscores a turning away, or, rather, a turning inward to the more urgent and intense image-world. Like some woefully under-recognised antipodean Proust, Murnane is fascinated by the mechanics of memory, which he sees as an operation of the image-world upon the actual, giving rise to the ‘true fictions’ that allow elements of the image-world to present themselves to awareness in a multiplicity of guises and versions. Murnane differs from many theorists of fiction in that he does not attribute primacy to the text but to the image-world to which the text gives access and which may contain, for instance, characters who have access, perhaps through their fictions, to image-worlds and characters inaccessible (at least as yet) to us. The million windows (from Henry James: “The house of fiction has in short not one window, but a million”) are those of “a house of two or maybe three storeys”, inhabited by writers, all perhaps versions or potential versions of Murnane himself, who look out over endless plains as they engage in the act of writing fiction, or discuss doing so. The multiplicity of this process stands in relation to an unattainable absolute towards which memories and other fictions reach, or, rather, which reaches to us in the form of memories and other fictions. Murnane’s small pallet, his precisely modulated recurring images and his looping, delightfully pedantic style are at once fascinating, frustrating, soporific and revelatory.

Take a Bite! Eat your way around the world by Aleksandra Mizielinska and Daniel Mizielinski {Reviewed by Stella}

Quite a few years ago, the wonderful Polish authors Aleksandra and Daniel Mizielinski were touring Aotearoa with the publisher and owner of Gecko Books, Julia Marshall. They came to Nelson and shared their love of illustration with a group of children. It was a delightful event, in which they communicated through drawings and their limited English. You might already own one of their wonderful books, the excellent Maps, or the architecture gem, H.O.U.S.E, and its sister, D.E.S.I.G.N, Impossible Inventions, or the earlier Mamoko series. Take a Bite is a big, glorious book about food around the world. It — of course! — has terrific illustrations, and covers the history of food across many countries and cuisines. Travel the world through this book, and discover intriguing facts about food and culture, cuisine specialties, cooking methods, site-specific ingredients, regional delights, marketplaces, harvesting and gathering, feasts, and sharing food — but wait, — recipes as well! While there’s plenty of history and food facts to keep the best questioner satisfied, it’s also an enjoyable visual experience with vibrant colour, excellent layout, and pockets of wit designed to hook young readers. Take A Bite is an excellent example of exploring the world and our cultural diversity through the universal enjoyment of food. So why not try a Polish pancake, Brazilian pralines, Moroccan Seffa, or Italian bolognese, or maybe you're keen for a spot of fermentation?

The spaceship Audition speeds on towards the event horizon. For it to continue, the three giants imprisoned within it must continue to speak. If they stop speaking they continue to grow larger and more unwieldy. Are the memories of which they speak their own, or a script? Is there even a past? A future? The novel Audition speeds on towards its end. For it to continue, the three characters imprisoned within it must continue to speak…

New books — just out of the carton! Click through for your copies now.

Blood and Dirt: Prison labour and the making of New Zealand by Jared Davidson $50

”Picture, for a minute, every artwork of colonial New Zealand you can think of. Now add a chain gang. Hard labour men guarded by other men with guns. Men moving heavy metal. Men picking at the earth. Over and over again. This was the reality of nineteenth-century New Zealand.” Forced labour haunts the streets we walk today and the spaces we take for granted. The unfree work of prisoners has shaped New Zealand's urban centres and rural landscapes and Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa — the Pacific — in profound and unsettling ways. Yet these stories are largely unknown: a hidden history in plain sight. Blood and Dirt explains, for the first time, the making of New Zealand and its Pacific empire through the prism of prison labour. Jared Davidson asks us to look beyond the walls of our nineteenth- and early twentieth-century prisons to see penal practice as playing an active, central role in the creation of modern New Zealand. A consummate history, illustrated throughout. Fascinating.

Rombo by Esther Kinsky (translated from German by Caroline Schmidt) $28

How does the impact of a disaster remain below the surface of consciousness, altering even the most unexpected things? In May and September 1976, two earthquakes ripped through north-eastern Italy, causing severe damage to the landscape and its population. About a thousand people died under the rubble, tens of thousands were left without shelter, and many ended up leaving their homes in Friuli forever. The displacement of material as a result of the earthquakes was enormous. New terrain was formed that reflects the force of the catastrophe and captures the fundamentals of natural history. But it is far more difficult to find expression for the human trauma, the experience of an abruptly shattered existence. In Rombo, Esther Kinsky’s new novel, seven inhabitants of a remote mountain village talk about their lives, which have been deeply impacted by the earthquake that has left marks they are slowly learning to name. From the shared experience of fear and loss, the threads of individual memory soon unravel and become haunting and moving narratives of a deep trauma. A remarkable piece of work.

”In Esther Kinsky’s new novel, language becomes the highest form of compassion and solidarity – not only with us human beings, but with the whole world, organic, non-organic, speaking out with many mouths and living voices. A miracle of a book; should be shining when it gets dark.” —Maria Stepanova

>>Writing itself anew.

>>Read Thomas’s review of Grove.

>>Read Thomas’s review of River.

The Wonders by Elena Medel (translated from Spanish by Thomas Bunstead and Lizzie Davis) $25

Maria and her granddaughter Alicia have never met. Decades apart, both make the same journey to Madrid in search of work and independence. Maria, scraping together a living as a cleaner and carer, sending money back home for the daughter she hardly knows; Alicia, raised in prosperity until a family tragedy, now trapped in a poorly paid job and a cycle of banal infidelities. Their lives are marked by precarity, and by the haunting sense of how things might have been different. Through a series of arresting vignettes, Elena Medel weaves together a broken family's story, stretching from the last years of Franco's dictatorship to mass feminist protests in contemporary Madrid. Audacious, intimate and shot through with razor-edged lyricism, The Wonders is a revelatory novel about the many ways that lives are shaped by class, history and feminism: about what has changed for working class women, and what has remained stubbornly the same.

”The Wonders is a poet's novel, delicate but strong, impressing its images firmly on the imagination.” —Hilary Mantel

”Completely unsentimental and with a harshness that hides the most radiant and painful of scars, The Wonders brings to life several generations of working women: it's a serene and impious novel that puts class, feminism, and the eternal complexity of family ties at the fore.” —Mariana Enriquez

>>Two interlocked spirals.

>>The struggle to determine the course of their own lives.

>>What shapes and defines us?

Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe $28

Acutely observed and beautifully written, Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes explores the enduring effects of racism (relevant anywhere), questions about loss, and the shapes of US Black life that emerge in the wake. In a series of 248 notes that gather meaning as we read them, Christina Sharpe skillfully weaves artifacts from the past — public ones alongside others that are poignantly personal — with present realities and possible futures, intricately constructing an immersive portrait of everyday Black existence. The themes and tones that echo through these pages — sometimes about language, beauty, memory; sometimes about history, art, photography, and literature — always attend, with exquisite care, to the ordinary-extraordinary dimensions of Black life. At the heart of Ordinary Notes is the indelible presence of the author's mother, Ida Wright Sharpe. "I learned to see in my mother's house," writes Sharpe. "I learned how not to see in my mother's house . . . My mother gifted me a love of beauty, a love of words." Using these gifts and other ways of seeing, Sharpe steadily summons a chorus of voices and experiences to the page. She practices an aesthetic of ‘beauty as a method’, collects entries from a community of thinkers toward a ‘Dictionary of Untranslatable Blackness’, and rigorously examines sites of memory and memorial. In the process, she forges a new literary form. A beautifully illustrated hardback.

>>Some notes.

>>Slips of the tongue.

>>Notes as form.

Eunuch by Kristina Carlson (translated from Finnish by Mikko Alapuro) $34

Wang Wei has always chosen his words carefully. His unobtrusive presence has seen him through the reign of five emperors, but now, as his own time is running out, he immerses himself in an unbridled account of a life confined at court during the Song dynasty in 12th century China. From the early separation from his parents, sisters, and brother – who did not survive the operation into a eunuch – to the power struggles he has witnessed and endured, Wang Wei examines human relationships with precision and a catching sense of wonder. While rumours are weapons, it is love and its various forms of expression that most fascinate Wang Wei.

”Adeptly using the very particular to get at the achingly universal, Eunuch is a short but striking meditation on difference and belonging. Someone who has always lived in-between will recognise that the stages of dusk are just as real as night and day. Elegant and earthy in turns, evoking whole worlds with deceptively simple words, Carlson’s writing recalls the aphoristic poetry of her narrator’s era.” —Kaisa Saarinen

>>Places I’ve never been.

George: A magpie memoir by Frieda Hughes $37

When Frieda Hughes moved to the depths of the Welsh countryside, she was expecting to take on a few projects: planting a garden, painting and writing her poetry column for the Times. But instead, she found herself rescuing a baby magpie, the sole survivor of a nest destroyed in a storm — and embarking on an obsession that would change the course of her life. As the magpie, George, grows from a shrieking scrap of feathers and bones into an intelligent, unruly companion, Frieda finds herself captivated — and apprehensive of what will happen when the time comes to finally set him free.

”There is an astringent beauty to Frieda Hughes's George. It's one of those books that appears to be about one thing-in this case, hand-rearing the eponymous orphan magpie-whilst being about something altogether more profound: love, loss and how inextricably linked they are. Love comes alive in Hughes' pages as an act of acute attentiveness. Loss lingers in the margins, but George doesn't baulk at the shadows. Instead, this book pulses with a defiant wonder at the living world, as wild and unruly as our feathered hero.'“ —Polly Morland

>>On George.

>>On living life like it matters.

>>On families.

Shadow Worlds: A history of the occult and esoteric in New Zealand by Andrew Paul Wood $50

A vigorous strand of interest in the occult, the spooky and the mysterious hasbeen part of our history since 1840. Shadow Worlds takes a lively look at communicating with spirits, secret ritualistic societies, the supernatural, the New Age — everything from The Golden Dawn and Rosicrucianism to Spiritualism, witchcraft and Radiant Living — and introduces the reader to a cast of fascinating characters who were generally true believers and sometimes con artists. It's a fresh and novel take on the history of a small colonial society that was notquite as ploddingly conformist as we may have imagined.

>>Not hobbits.

Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry and the mysteries of mental illness by Andrew Scull $32

For more than two hundred years, disturbances of reason, cognition and emotion — the sort of things that were once called 'madness' — have been described and treated by the medical profession. Mental illness, it is said, is an illness like any other — a disorder that can be treated by doctors, whose suffering can be eased, and from which patients can return. And yet serious mental illness remains a profound mystery that is in some ways no closer to being solved than it was at the start of the twentieth century. In this provocative exploration of psychiatry, sociologist Andrew Scull traces the history of its attempts to understand and mitigate mental illness — from the age of the asylum and unimaginable surgical and chemical interventions, through the rise and fall of Freud and the talking cure, and on to our own time of drug companies and antidepressants. Through it all, Scull argues, the often vain and rash attempts to come to terms with the enigma of mental disorder have frequently resulted in dire consequences for the patient.

”There are few heroes in this enraging study of a great failing. Fascinating.” —Sebastian Faulks

”Meticulously researched and beautifully written.” —Guardian

”I would recommend this fascinating, alarming and alerting book to anybody. For anyone referred to a psychiatrist it is surely essential.” —Horatio Clare

The Martins by David Foenkinos (translated from French by Sam Taylor) $35

Is it true that every life is the stuff of novels? Or are some people just too ordinary?

This is the question a struggling Parisian writer asks when he challenges himself to write about the first person he sees when he steps outside his apartment. Secretly hoping to meet the beautiful woman who occasionally smokes on his street, he instead sets eyes on octogenarian Madeleine. She's happy to become the subject of his project, but first she needs to put her shopping away. Wondering if his project is doomed to be hopelessly banal, he soon finds himself tangled in the lives of Madeleine's family. Though calm on the surface, the Martins have secrets, troubles and woes, and the writer discovers that the most compelling story is that of an ordinary life. This clever and charming book interrogates the ways in which novels are written, and their relationship to the so-called real world, and assails the perceived schism between the ;literary’ and the ‘mundane’.

”Playing with the rules of autofiction and family comedy, Foenkinos has created a multi-layered novel.” —Le Parisien

>>Trailer.

>>Foenkinos in conversation.

Cobalt Red: How the blood of the Congo powers our lives by Siddharth Kara $55

An unflinching investigation reveals the human rights abuses behind the Congo's cobalt mining operation — and the moral implications that affect us all.

Cobalt Red is the searing, first-ever exposé of the immense toll taken on the people and environment of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by cobalt mining, as told through the testimonies of the Congolese people themselves. Activist and researcher Siddharth Kara has traveled deep into cobalt territory to document the testimonies of the people living, working, and dying for cobalt. To uncover the truth about brutal mining practices, Kara investigated militia-controlled mining areas, traced the supply chain of child-mined cobalt from toxic pit to consumer-facing tech giants, and gathered shocking testimonies of people who endure immense suffering and even die mining cobalt. Cobalt is an essential component to every lithium-ion rechargeable battery made today, the batteries that power our smartphones, tablets, laptops, and electric vehicles. Roughly 75 percent of the world's supply of cobalt is mined in the Congo, often by peasants and children in sub-human conditions. Billions of people in the world cannot conduct their daily lives without participating in a human rights and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

>>Unbearable.

Introducing Te Tiriti o Waitangi by Claudia Orange and Jared Davidson $18

In 1840, over 500 Maori leaders put their names to a significant new document: Te Tiriti o Waitangi or the Treaty of Waitangi. Through their signatures, moko or marks they were making an agreement with the British Crown. At stake was the sovereignty of the country, the governance of the land. The history of this agreement is a remarkable one, and ignorance about the centrality of the agreement continues to lead to conflict and prejudice.

Introducing He Whakaputanga by Vincent O’Malley and Jared Davidson $18

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni/The Declaration of Independence of New Zealand was signed by fifty-two rangatira from 1835 to 1839. It was a powerful assertion of mana and rangatiratanga, made after decades of Maori and European encounters that had been steadily expanding — both within Aotearoa New Zealand and elsewhere on the globe as Maori travelled abroad. As rangatira reached out, they also forged new alliances. He Whakaputanga was part of that process, reinforcing ties between northern rangatira and the British Crown that dated back nearly half a century.

Introducing the Women’s Suffrage Petition, 1893 by Barbara Brookes and Jared Davidson $18

In 1893 New Zealand became the first country in the world with universal suffrage: all New Zealand women now had the right to vote. This achievement owed much to an extraordinary document: the 1893 Women’s Suffrage Petition. Over 270 metres long, with the signatures of some 24,000 women (and at least twenty men), the Suffrage Petition represents the culmination of many years of campaigning by suffragists, led by Kate Sheppard, and women throughout the country.

The Mystery at Dunvegan Castle by T.L. Huchu $38

Ropa Moyo is no stranger to magic or mysteries. But she's still stuck in an irksomely unpaid internship. So she's thrilled to attend a magical convention at Dunvegan Castle, on the Isle of Skye, where she'll rub elbows with eminent magicians. For Ropa, it's the perfect opportunity to finally prove her worth. Then a librarian is murdered and a precious scroll stolen. Suddenly, every magician is a suspect, and Ropa and her allies investigate. Trapped in a castle, with suspicions mounting, Ropa must contend with corruption, skullduggery and power plays. Time to ask for a raise? The third in the excellent ‘Edinburgh Nights’ series.

”Tendai's alternative Edinburgh becomes more real and more exciting with every book. An artful combination of magic, history and imagination wrapped up in an engaging story.” —Ben Aaronovitch

With so much of our personal and collective cultures revolving around a dinner plate, our appetite for reading about food (and its place in our lives and in the lives of others) is insatiable.

Essayist, poet, and pie lover Kate Lebo is inspired by twenty-six fruits. She expertly blends the culinary, medical, and personal in The Book of Difficult Fruit. A is for Aronia, M is for Medlar, and Q is for Quince. Claudia Roden describes it as “ A beautiful, fascinating read full of surprises – a real pleasure.”

What did we eat and when did we eat it? Over the ten chapters of Food: The history of taste, food historian covers the history of food from the hunter-gathers and first farmers to the evolution of the restaurant and the contemporary volume of choice from fast food to slow cooking. Want to know the food fashions of the Renaissance, what they ate during the Industrial Revolution, or the ancient diets of Greece and Rome, this is your book.

Ah, honey! Thinking about getting some bees? Read this delightful account of two men who decide to become beekeepers, learning about nature and about themselves in the process. Inspiring Liquid Gold . “A great book. Painstakingly researched, but humorous, sensitive and full of wisdom. I'm on the verge of getting some bees as a consequence of reading the book.” - Chris Stewart, author of Driving Over Lemons

My First Popsicle is as much an ode to food and emotion as it is to life. A collection of essays edited by actor Zosia Mamet. Contributors include David Sedaris, Patti Smith, Jia Tolentino, and Ruth Reichl. The Kirkus review gave it a thumbs up for gifting. “Most of the essays capture an isolated moment in time, making the book perfect for reading in short, leisurely spurts..the book is an appealing reminder of the power of food...A good gift for foodies." -Kirkus

First Catch is a beautifully written appreciation of making a meal. Stand next to Thom Eagle in the kitchen as he muses on the very best way to coax flavour out of an onion (slowly, and with more care than you might expect), or considers the crucial role of salt in the creation of the perfect assembly for early green shoots and leaves. “A one-off, the kind of food book that I believed was no longer being published ... when I reached the last page, I went back to the beginning.” —Bee Wilson, The Times

Bill Buford's Dirt is a vivid, hilarious, intimate account of his five-year odyssey in French cuisine. Never mind that he spoke no French, had no formal training, knew no one in Lyon, and his wife and twin toddlers lived in New York. A feast of a book. “Buford is excellent company - candid, self-deprecating and insatiably, omnivorously interested... [I] wolfed it down.“ - Orlando Bird, Telegraph

Cooking is thinking! Small Fires is an electrifying, innovative memoir. Rebecca May Johnson rewrites the kitchen as a vital source of knowledge and revelation. Drawing on insights from ten years spent thinking through cooking, she explores the radical openness of the recipe text, the liberating constraint of apron strings, and the transformative intimacies of shared meals. Excellent food writing. 'One of the most original food books I've ever read, at once intelligent and sensuous, witty, provoking and truly delicious, a radical feast of flavours and ideas.' - Olivia Laing

In The Kitchen is a thoughtful and inventive book of essays highlighting our personal relationships with food. Rachel Roddy traces an alternative personal history through the cookers in her life; Rebecca May Johnson considers the radical potential of finger food; Ruby Tandoh discovers a new way of thinking about flavour through the work of writer Doreen Fernandez; and Yemisi Aribisala remembers a love affair in which food failed as a language.

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Read our #339th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending. You might just end up with a new book or two (or several (worse could happen)).

21 July 2023

Lioness by Emily Perkins

A new Emily Perkins novel is a rare thing (the last being The Forrests in 2012). She’s been writing plays and teaching. And what good things they are. Her take on Isben’s A Doll’s House, which played at the Theatre Royal a few years ago, was superb. So lucky us, it’s a Donna Tart moment this year with the Lioness. It’s always nerve-wracking when a favourite author has a new work. Will you still like their style? Can you resist the temptation to compare? And will this grip you as other writings have? So, the book lands. The cover is shocking and intriguing. A burnt out face. The novel cracks in from the start with our protagonist, Therese having average sex with her older husband, and then discovering, a few pages in, the Viagra tucked away in the suitcase. You sense an unravelling is to begin. Life is too neat. Therese too plastic. Later you realise, malleable. Not by circumstance, rather by choice. A choice to have her ‘dream’ homewares brand, to please everyone even at the loss of her own identity, and to stay quiet when she would rather speak out. You can wear the silk jumpsuit, attend the right events, and host the perfect party, but the girl from the Valley will still appear unexpectedly. There are sneaky tell-tale clues of her other life, of her other self. The drink of choice, rum and coke, the occasional slip in language, and the pulse of something wild just under the surface. This surface will crack open when her developer husband has the spotlight of a fraud enquiry turned on him. Conveniently, in the downstairs apartment is another middle-aged, middle-class (although not quite as privileged or wealthy as Therese) woman, Claire, having an epiphany or crisis — take your pick. While reading this I had the same discomfort as when I read Rachel Cusk’s Second Place. These people — what’s wrong with them? It’s hard to like any of them, even Therese and Claire (the first you have some empathy for, the second yeah, okay, break out if you really need to), especially those adult children who treat Therese (wife number two and not their mother) appallingly. They are universally horrendous. So, what keeps you there, with the Lioness? The writing, as ever, is excellent; Perkin’s observations are squirmingly spot on; the irony and social commentary eviscerating. I loved this more once I closed the pages and left those characters behind. Much like, Cusk’s Second Place, it will make you shudder and laugh simultaneously.

Blush by Jack Robinson, with photographs by Natalia Zagórska-Thomas

I do not blush, I cannot make myself blush nor put myself in a situation where I would blush, but a blusher cannot help but blush. A blush, according to Darwin, is "the most peculiar and the most human of all expressions," and the expression over which blushers have the least control. It is a signal that subverts all systems of signalling, one that exists below the reach of the intentional and intellectual strata of signalling systems and one that therefore cannot be hidden or misrepresented by them. In this a blush is in a sense unique. A blush can only be authentic, because involuntary, which not only makes a blusher especially awkward, exposed and vulnerable but also, precisely because of these qualities, gives blushing a special attractive power, an authenticity that is imitated by cosmetics but so unconvincingly as to border on irony. “A blush is a quick-motion bruise. A blush is a passing wound, subcutaneous, the blood seeking release but the skin holding tight,” writes Robinson in this thoughtful exploration of the phenomenon of blushing. Blood rushes towards the the locus of action, in the case of a blush towards the interface between the private and the public worlds, towards the tissue where the body ends, where otherness begins. There is “a chink, a gap, a little slippage between me and the other me, the one I’m performing — where the blush gets in.” A blush is a transgression of the customary border between the personal and the public, the border upon which both the world outside us and we ourselves heap so many expectations, personae and intentions, expectations; personae and intentions that are rendered null by a blush. A blush is regarded as embarrassing in the context of these expectations, personae and intentions, both from society and ourselves, but therein lies also the beauty and liberating power of the blush in a world in the grip of a crisis of authenticity, where “we live on the cusp between ignorance and oblivion.” The intimate/over-intimate presentation of a blush is “an index of confusion,” and has the same utility as other indices, where the blood rises to the surface of a book and shows us a way through all that prose. In Blush, Jack Robinson (one of the pseudonyms of Charles Boyle, publisher of the ever-wonderful CB Editions), provides a subtle and insightful phenomenology and social history of blushing alongside witty and equally subtle and insightful images by Natalia Zagórska-Thomas (some more of her work can be seen here), each and both displaying the virtue of lightness that lends their work a polyvalent concision that enables it to keep generating meaning for a considerable time after the reading/viewing has been ostensibly completed.

What you have always needed and couldn’t find: an accessible and comprehensive identification guide to fungi of Aotearoa! Forager and fungi enthusiast Liv Sisson’s Fungi of Aotearoa: A Curious Forager’s Field Guide is a must for every household. Whether you are a forager, mushroom lover, or just plain curious about these most intriguing of organisms, this book covers all the bases: identification, fascinating facts, foraging tips, and the best ways to cook your fungi are all here in a beautiful package with excellent photography (by Paula Vigus) and descriptions of more than 130 species. And still small enough for your backpack! Perfect. The first print run sold out immediately, but it’s back — and to celebrate we are offering you a special price: $40 (RRP $45) this week only (promotion ends 28.7.32). Use the promotion code: FUNGI at the checkout on our website, or email us your request.

New books — just out of the carton! Click through for your copies now.

Art Monsters: Unruly bodies in feminist art by Laren Elkin $65

For decades, feminist artists have confronted the problem of how to tell the truth about their experiences as bodies. Queer bodies, sick bodies, racialised bodies, female bodies, what is their language, what are the materials we need to transcribe it? Exploring the ways in which feminist artists have taken up this challenge, Art Monsters is a landmark intervention in how we think about art and the body, calling attention to a radical heritage of feminist work that not only reacts against patriarchy but redefines its own aesthetic aims. Elkin demonstrates her power as a cultural critic, weaving links between disparate artists and writers — from Julia Margaret Cameron's photography to Kara Walker's silhouettes, Vanessa Bell's portraits to Eva Hesse's rope sculptures, Carolee Schneemann's body art to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha's trilingual masterpiece DICTEE — and shows that their work offers a potent celebration of beauty and excess, sentiment and touch, the personal and the political.

”Destined to become a new classic.” —Chris Kraus

”Juxtaposes ideas, images, language, in a vivid collage that invites us to look more deeply.” —Jeanette Winterson

”Soaring and vivid. It left me giddy with possibility.” —Doireann Ni Ghriofa

”A fascinating re-visioning and re-imagining of women artists who have used their bodies in all sorts of creative, subversive ways.” —Juliet Jacques

”You won't find anything like this history, told in this way, anywhere else.” —Lubaina Himid

>>Delving into the history.

Lost on Me by Veronica Raimo (translated from Italian by Leah Janeczko) $35

Vero has grown up in Rome with her eccentric family: an omnipresent mother who is devoted to her own anxiety, a father ruled by hygienic and architectural obsessions, and a precocious genius brother at the centre of their attention. As she becomes an adult, Vero's need to strike out on her own leads her into bizarre and comical situations: she tries (and fails) to run away to Paris at the age of fifteen; she moves into an unwitting older boyfriend's house after they have been together for less than a week; and she sets up a fraudulent (and wildly successful) street clothing stall to raise funds to go to Mexico. Most of all, she falls in love — repeatedly, dramatically, and often with the most unlikely and inappropriate of candidates. As she continues to plot escapades and her mother's relentless tracking methods and guilt-tripping mastery thwart her at every turn, it is no wonder that Vero becomes a writer — and a liar — inventing stories in a bid for her own sanity. Narrated in a voice as wryly ironic as it is warm and affectionate, Lost on Me seductively explores the slippery relationship between deceitfulness and creativity (beginning with Vero's first artistic achievement: a painting she steals from a school classmate and successfully claims as her own).

”I fell head over heels in love with Lost on Me. What a thrillingly original voice! Raimo writes with a tender brutality that is simultaneously hilarious and heartbreaking.” —Monica Ali

”Many of the pages are jellyfish stings: they burn on and on.” —Claudia Durastanti

”Lost on Me is the naughty grandson of Natalia Ginzburg's Family Lexicon. Raimo has tapped the novelistic potential of her affections and has transformed them into comedy.” —Il Corriere della Sera

>>Read an extract.

Look! Said the Little Girl by Tania Norfolk, illustrated by Aleksandra Szmidt $22

A man and a little girl share their unique way of seeing and hearing the world around them. "Look," said the little girl, "a ladybird!" "A ladybird!" said the old man. "What does she look like?" "Like a tiny turtle in fancy dress — a red polka-dot coat that's hiding a secret." "Wings?" whispered the old man. "Yes, wings," whispered the little girl. "That is a very good secret." As they walk, a young girl describes the things she sees to an elderly, visually impaired man, who turns the tables when he describes to the child what it is that he hears. A delightful book (reminiscent of Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present) from a Nelson author.

>>Meet the author!

I Will Write to Avenge My People by Annie Ernaux (translated from French by Alison L. Strayer) $26

'I will write to avenge my people.' It was as a young woman that Annie Ernaux first wrote these words in her diary, giving a name to her purpose in life as a writer. She returns to them in her stirring defence of literature and of political writing in her Nobel Lecture, delivered in Stockholm on 7 December 2022. To write of her own life, she asserts, is to 'shatter the loneliness of experiences endured and repressed'; to mine individual experience is to find collective emancipation. Ernaux's speech is a bold assertion of the capacity of writing to give people a sense of their own worth, and of one writer's commitment to bearing witness to life, its joys and its injustices.

>>Books by Annie Ernaux.

>>Ernaux delivers the Nobel lecture.

Ringakōreko / Dazzlehands by Sacha Cotter and Josh Morgan; te reo Māori version by Kawata Teepa $22

The pig won’t say, “Oink”.

”A book bursting with riotous colour and energy. From the authors of the award-winning The Bomb, another excellent and highly enjoyable story about diversity and individuality. Playful language and the best pig ever.” —Stella

A Cage in Search of a Bird by Florence Noiville (translated from French by Teresa Lavender Fagan) $30

— Laura Wilmote is a television journalist living in Paris. Her life couldn't be better-a stimulating job, a loving boyfriend, interesting friends — until her phone rings in the middle of one night. It is C., an old school friend whom Laura recently helped find a job at the same television station: "My phone rang. I knew right away it was you." Thus begins the story of C.'s unrelenting, obsessive, incurable love/hatred of Laura. She is convinced that Laura shares her love, but cannot — or will not — admit it. C. begins to dress as Laura, to make her friends and family her own, and even succeeds in working alongside Laura on the unique program that is Laura's signature achievement. The obsession escalates, yet is artfully hidden. It is Laura who is perceived as the aggressor at work, Laura who appears unwell, Laura who is losing it. Even Laura's adoring boyfriend begins to question her. Laura seeks the counsel of a psychiatrist who diagnoses C. with De Clérambault syndrome — she is convinced that Laura is in love with her. And worse, the syndrome can only end in one of two ways: the death of the patient, or that of the object of the obsession. A Cage in Search of a Bird is the gripping story of two women caught in the vice of a terrible delusion. Florence Noiville brilliantly narrates this story of obsession and one woman's attempts to escape the irrational love of another — an inescapable, never-ending love, a love that can only end badly.

”Look into the mirror, you might not recognise what you see. Watch someone else gaze into the exact same mirror, you might just see yourself. Noiville tackles issues of identity and belonging like few other novelists. A Cage in Search of a Bird is smart, suspenseful, and powerful.” —Colum McCann

You, Bleeding Childhood by Michele Mari (translated from Italian by Brian Robert Moore) $38

Raised on comic books and science fiction, the young Mari constructed an alternate universe for himself untouched by uncomprehending grownups or sadistic peers. Compared to the horrors of real life, Long John Silver and Cthulhu made for positively cuddly company; but little boys raised by beasts may well grow up beastly — or never grow up at all. Waking or sleeping, the obsessions of Mari's youth seem to colour his every adult thought. You, Bleeding Childhood stands as his first attempt to catalog this cabinet of wonders. Cult classics since their first publication in Italy but appearing in English for the first time, these loosely connected stories stand as the ideal introduction to an encyclopedic fantasist often compared with Kafka, Poe, and Borges.

”Emotion, anger, nostalgia: but also affectionate humour, indulgent sympathy in a work that masterfully combines elegance and irony, psychological acumen and an understanding of form, eclectic culture and emotional vulnerability. The work of a child who developed an unstoppable passion for adventure books, for comics, who cultivated a fetishistic relationship with thought, with the imagination; but also with a stubborn self, wounded by the intensity of his perceptions.” —Alida Airaghi

The Lost Rainforests of Britain by Guy Shrubsole $50

In 2020, writer and campaigner Guy Shrubsole moved from London to Devon. As he explored the wooded valleys, rivers and tors of Dartmoor, he discovered a spectacular habitat that he had never encountered before: temperate rainforest. Entranced, he would spend the coming months investigating the history, ecology and distribution of rainforests across England, Wales and Scotland. Britain, Shrubsole discovered, was once a rainforest nation. This is the story of a unique habitat that has been so ravaged, most people today don't realise it exists. Temperate rainforest may once have covered up to one-fifth of Britain and played host to a dazzling variety of luminous life-forms, inspiring Celtic druids, Welsh wizards, Romantic poets, and Arthur Conan Doyle's most loved creations. Though only fragments now remain, they form a rare and internationally important habitat, home to lush ferns and beardy lichens, pine martens and pied flycatchers. But why are even environmentalists unaware of their existence? And why have they been so comprehensively excise them from cultural memory?

”A magnificent and crucial book that opens our eyes to untold wonders.” —George Monbiot

Cousins by Aurora Venturini (translated by Kit Maude) $33

Widely regarded as Venturini's masterpiece, Cousins is the story of four women from an impoverished, dysfunctional family in La Plata, Argentina, who are forced to suffer a series of ordeals including disfigurement, illegal abortions, miscarriages, sexual abuse and murder, narrated by a daughter whose success as a painter offers her a chance to achieve economic independence and help her family as best she can. Neighborhood mythologies, family, female sexuality, vengeance, and social mobility through art are explored and scrutinized in the unmistakable voice of an unforgettable protagonist, Yuna, who stares wildly at the world in which she is compelled to live; a voice unique in its candidness, sharp edge and breathtaking power.

>>Cruelty and survival.

Ways of Being: Animals, plants, machines; The search for a planetary intelligence by James Bridle $32

What does it mean to be intelligent? Is it something unique to humans or shared with other beings — beings of flesh, wood, stone, and silicon? The last few years have seen rapid advances in ‘artificial’ intelligence. But rather than a friend or companion, AI increasingly appears to be something stranger than we ever imagined, an alien invention that threatens to decenter and supplant us. At the same time, we're only just becoming aware of the other intelligences that have been with us all along, even if we've failed to recognize or acknowledge them. These others — the animals, plants, and natural systems that surround us — are slowly revealing their complexity, agency, and knowledge, just as the technologies we've built to sustain ourselves are threatening to cause their extinction and ours. What can we learn from them, and how can we change ourselves, our technologies, our societies, and our politics to live better and more equitably with one another and the nonhuman world?

”Bridle's writing weaves cultural threads that aren't usually seen together, and the resulting tapestry is iridescently original, deeply disorientating and yet somehow radically hopeful. The only futures that are viable will probably feel like that. This is a pretty amazing book, worth reading and rereading.” —Brian Eno

Vietnamese Vegetarian by Uyen Luu $50

From quick dishes such as Sweet Potato Noodles with Roasted Fennel and Sweetheart Cabbage and Grilled Vegetable Banh Mi, to dishes fit for a feast such as Mushroom and Tofu Phở and Rice Paper Pizza, as well as sweet treats like Rainbow Dessert and Lotus and Sweet Potato Rice Pudding, there is a vast array of dishes for any occasion. With tips and tricks on how to adapt the recipes to use alternative ingredients, this is bound to be everyone’s go-to book on vegetarian Vietnamese food.

>>Look inside!

The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel exports the technology of occupation around the world by Antony Loewenstein $40

For more than 50 years, the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza has given the Israeli state invaluable experience in controlling an 'enemy' population, the Palestinians. It's here that they have perfected the architecture of control, using the occupied Palestinian territories as a testing ground for weaponry and surveillance technology that they then export around the world. The Palestine Laboratory shows in depth and for the first time how Israel has become a leader in developing spying technology and defence hardware that fuels some of the globe's most brutal conflicts — from the Pegasus software that hacked Jeff Bezos's and Jamal Khashoggi's phones, and the weapons sold to the Myanmar army that has murdered thousands of Rohingyas, to the drones being used by the European Union to monitor refugees in the Mediterranean who are left to drown. In important investigation.

”This is a must-read on a hidden and shocking aspect of the Israeli colonisation of the Palestinians. This book shows clearly that this kind of export is now Israel's most significant contribution to the global violation of human rights.” —Ilan Pappe

”A triumph of investigative journalism. It exposes the ruthlessness with which Israel exploits the experience gained from the illegal occupation to export all kinds of military hardware as well as the technology of surveillance, espionage, cyber warfare, phone-hacking, and house demolition. It also shines a torch on the dark side of Israel's support for despots around the world. Altogether, a profoundly depressing audit on a country that used to boast of being ‘a light unto the nations’.” —Avi Shlaim

>>A testing ground for war tech.

Wrecked by Heather Henson $21

A gritty YA novel about three teens, caught in the middle of the opioid crisis in rural Appalachia. For as long as Miri can remember it's been her and her dad, Poe, in Paradise — what Poe calls their home — hidden away from prying eyes in rural Kentucky. It's not like Miri doesn't know what her dad does or why people call him ‘the Wizard’. It's not like she doesn't know why Clay, her one friend and Poe's right-hand man, patrols the grounds with a machine gun. It's nothing new, but lately Paradise has started to feel more like a prison. Enter Fen. The new kid in town could prove to be exactly the distraction Miri needs...but nothing is ever simple. Poe doesn't take kindly to strangers. Fen's DEA agent father is a little too interested in Miri's family. And Clay isn't satisfied with being just friends with Miri anymore. But what's past is prologue — it's what will follow that will wreck everything.

The Last Drop: Solving the world’s water crisis by Tim Smedley $40

Water scarcity is the next big climate crisis. Water stress — not just scarcity, but also water-quality issues caused by pollution — is already driving the first waves of climate refugees. Rivers are drying out before they meet the oceans and ancient lakes are disappearing. It's increasingly clear that human mismanagement of water is dangerously unsustainable, for both ecological and human survival. And yet in recent years some key countries have been quietly and very successfully addressing water stress. How are Singapore and Israel, for example — both severely water-stressed countries — not in the same predicament as Chennai or California?

McSweeney’s #70 edited by James Yeh $50

Inludes Patrick Cottrell's story about a surprisingly indelible Denver bar experience; poignant, previously untranslated fiction from beloved Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen; Argentine writer Olivia Gallo's English language debut about rampaging urban clowns; the rise and fall of an unusual family of undocumented workers in rural California by Francisco González; and Indian writer Amit Chaudhuri's sojourn to the childhood home of Brooklyn native Neil Diamond. Readers will be sure to delight in Guggenheim recipient Edward Gauvin's novella-length memoir-of-sorts in the form of contributors' notes, absorbing short stories about a celebrated pianist (Lisa Hsiao Chen) and a reclusive science-fiction novelist (Eugene Lim), flash fiction by Véronique Darwin and Kevin Hyde, and a suite of thirty-six very short stories by the outsider poet Sparrow. Plus letters from Seoul, Buenos Aires, Las Vegas, Philadelphia, and Lake Zurich, Illinois, by E. Tammy Kim, Drew Millard, and more.

>>Look inside.

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris