A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #359th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending — and get your seasonal gift-choosing done!

8 December 2023

A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #359th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending — and get your seasonal gift-choosing done!

8 December 2023

Did you know we have a category on our shop website (volumebooks.online) called ‘Place’?

Here you can find books about a particular country, set predominately in that place or written by an author of that country. This section covers various genres from history to art to fiction. Interested in Asia, here you will find the latest novel set in Malaysia from Tan Twan Eng, House of Doors, the excellent Japanese Australian author Jessica Au’s award-winning Cold Enough for Snow, and Aotearoa’s Joanna Cho’s delightful collection People Person, as well as cookbooks (the beautiful Parsi spanning from Persia to Bombay) and one of my favourite woman’s history accounts, Stranger in the Shogun’s City. In The Passenger travel series, we have Japan and India. Have a wander around some places and discover history, culture, and fiction authors new to you. And possibly, the right gift for someone special.

Exteriors by Annie Ernaux (translated by Tanya Leslie)

I would like the work to be a non-work, I thought, though it was not exactly my thought or a new thought. I would like a literature that revealed as much as possible of what we call real life, that was as close as possible to real life, so close, perhaps that it cannot be distinguished from what we call real life. Is such a thing possible, I wondered, as I read Annie Ernaux’s Exteriors, a book drawn from her journal entries over a period of seven years, entries in which she is attempting to exclude as much as possible of herself and of her past from her writing and, as much as this is possible, and her work is perhaps testing to what extent this is possible, to observe and record the actual particulars that present themselves to her as she travels on Métro or the RER after moving to a New Town just outside Paris, if it is the case that details are themselves active in their presentation, which is somehting of which I am not certain. “It is other people,” Ernaux writes, “who revive our memory and reveal our true selves through the interest, the anger or the shame that they send rippling through us.” She cannot help but write some of her own thoughts, probably more than she knows or intends, which is not surprising, I thought, it is not that easy to excise yourself entirely, everything you notice points primarily to you who do the noticing. “(By choosing to write in the first person, I am laying myself open to criticism. … The third person is always somebody else. … ‘I’ shames the reader,)” she writes. Meticulously recording her observations gives Ernaux insight not just into the people she observes, their lives are mostly withheld from her, after all, there are only the moments, but, I thought, we exist in any case only in moments, but into the society, into the world, for which these particulars are what literary types might call text and what medical types might call symptoms. As Ernaux observes she observes herself being the kind of person who observes in the way that only she observes. “(I realise that I am forever combing reality for signs of literature,)” she says in an aside. “(Sitting opposite someone in the Métro, I often ask myself, ‘Why am I not that woman?’)” For Ernaux so-called real life is a text, but artless, raw. She observes the performative efforts of other people in public places, on public transport. “Contrary to a real theatre, members of the audience here avoid looking at the actors and affect not to hear their performance. Embarrassed to see real life making a spectacle of itself, and not the opposite.” The extent to which artifice can be removed is the extent to which, ultimately, our mostly unconscious responses to the external reveal something about ourselves. This is what it means to exist. “It is outside my own life that my past existence lies: in passengers commuting on the Métro or the RER; in shoppers glimpsed on escalators at Auchan or in the Galleries Lafayette; in complete strangers who cannot know that they possess part of my story; in faces and bodies which I shall never see again. In the same way, I myself, anonymous among the bustling crowds on streets and in department stores, must secretly play a role in the lives of others.” The purpose of art is to remove itself. Or to reduce itself. Just as the perfect crime is one so subtle that is never discovered, so it is with the perfect artwork, I thought, the perfect art ‘passes' as ordinary life. The work becomes a non-work. Well, I thought, I will write no more.

From the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Tinkers comes a lyrical historical novel, This Other Eden. As beguiling as the cover of this book, Harding’s writing has been described as ‘painted imagery’ and as ‘angelic sentences’. Like his earlier works, this is set in New England, this time on the imagined Apple Island, based on the historical Malaga Island off the coast of Maine, home to a racially mixed fishing community from the Civil War up until the early 20th century. It’s a story of a community on borrowed time.

Short-listed for this year’s Booker Prize, the judges said: “Based on a relatively unknown true story, Paul Harding’s heartbreakingly beautiful novel transports us to a unique island community scrabbling a living. The panel were moved by the delicate symphony of language, land and narrative that Harding brings to bear on the story of the islanders.”

This Other Eden is rich in language and imagery with unforgettable characters. A handsome gift in this hardback edition, or a perfect addition to your summer reading pile.

A new book is a promise of good times ahead. Click through for your copies:

So Late in the Day by Claire Keegan $23

An exquisitely written new story from the author of the indelible Small Things Like These and Foster. After an uneventful Friday at the Dublin office, Cathal faces into the long weekend and takes the bus home. There, his mind agitates over a woman named Sabine with whom he could have spent his life, had he acted differently. All evening, with only the television and a bottle of champagne for company, thoughts of this woman and others intrude — and the true significance of this particular date is revealed. From one of the finest writers working today, Keegan's new story asks if a lack of generosity might ruin what could be between men and women. Is it possible to love without sharing?

Little Dead Rabbit by Astrid Alben and Zigmunds Lapsa $48

A collaboration between poet Astrid Alben and visual artist and designer Zigmunds Lapsa, a book-length poem with die-cut images throughout. During the lockdown of 2020/21, Alben and Lapsa worked closely together on this book-length poem that is part adult fairy-tale, part concrete poem about a little dead rabbit the poet found on the verge of a road. Ostensibly a poem about death, the small corpse is equally a meditation on healing and joy.

Sublunar by Harald Voetmann (translated from Danish by Johanne Sorgenfri Ottosen) $38

In the 16th century, on the island of Hven, the pioneering Danish astronomer, Tycho Brahe, is undertaking an elaborate study of the night sky. A great mind and a formidable personality, Brahe is also the world's most illustrious noseless man of his time. Told by Brahe and his assistants — a filthy cast of characters — Sublunar is both novel and almanac. Alongside sexual deviancy, spankings, ruminations on a new nose — flesh, wood, or gold? — Brahe (a choleric and capricious character) and his peculiar helpers take painstainking measurements that will revolutionize astronomy, long before the invention of the telescope. Meanwhile the plague rages in Europe... The second in Voetmann's triptych of historical novels, Sublunar is as visceral, absurd, and tragic as its predecessor Awake (which focussed on Pliny the Elder) but with a special nocturnal glow and a lunatic-edged gaze trained on the moon and the stars.

”Reading Voetmann’s books makes me feel so alive. His voice is like no other, his hold on his material masterful.” —Olga Ravn

”Voetmann seems to work from the ground up. Although Awake and Sublunar might be called novels of ideas, Voetmann's intellectual concerns are not forcefully imposed upon fictional dramas arbitrarily designed to illustrate them, but rather arise from particulars that are irreducible. Each page of the books contains a richness of detail and a depth of attention that has all but vanished from the contemporary novel—or, for that matter, any other mass-produced object. The novels themselves—each scarcely more than a hundred pages— are miniatures that appear to have been less written than chiseled. Images glow in stark relief against the somber backdrops and recur with slight variations, as though guided by a Fibonacci sequence. Amid the guts and gore, there are moments of quiet splendour. —New York Review of Books

Held by Anne Michaels $33

1917. On a battlefield near the River Escaut, John lies in the aftermath of a blast, unable to move or feel his legs. Struggling to focus his thoughts, he is lost to memory a chance encounter in a pub by a railway, a hot bath with his lover on a winter night, his childhood on a faraway coast as the snow falls. 1920. John has returned from war to North Yorkshire, near another river alive, but not still whole. Reunited with Helena, an artist, he reopens his photography business and endeavours to keep on living. But the past erupts insistently into the present, as ghosts begin to surface in his pictures — ghosts whose messages he cannot understand. So begins a narrative that spans four generations, moments of connection and consequence igniting and re-igniting as the century unfolds. In luminous moments of desire, comprehension, longing, transcendence, the sparks fly upward, working their transformations decades later.

”Through luminous moments of chance, change, and even grace, Michaels shows us our humanity - its depths and shadows.” —Margaret Atwood

”Dazzling lyrical snapshots recall the dreamlike style of Fugitive Pieces in the poet's third novel, a fluid examination of history, memory and generational trauma. The writing is always personal, hypersensitive and profoundly interior. Michaels's writing continues to stand head and shoulders above most other fiction. At the heart of this book lies the question of how goodness and love can be held across the generations.” —Observer

Start Here: Instructions for becoming a better cook by Sohla El-Waylly $70

A really clear and useful practical, information-packed, and transformative guide to becoming a better cook and conquering the kitchen, this is a must-have masterclass in leveling up your cooking. Across a dozen technique-themed chapters — from "Temperature Management 101" and "Break it Down & Get Saucy" to "Mix it Right," "Go to Brown Town," and "Getting to Know Dough" — Sohla El-Waylly explains the hows and whys of cooking, introducing the fundamental skills that you need to become a more intuitive, inventive cook. A one-stop resource, regardless of what you're hungry for, Start Here gives equal weight to savory and sweet dishes, with more than 200 mouthwatering recipes. Packed with practical advice and scientific background, helpful tips, and an almost endless assortment of recipe variations, along with tips, guidance, and how-tos, Start Here is culinary school — without the student loans.

‘Other Stations Are Shit’: Student radio in Aotearoa New Zealand by Matt Mollgaard and Karen Neill $40

From its beginnings in 1969 as a student capping stunt, student radio has gone on to become an influential source of music and culture across Aotearoa New Zealand. Fresh sounds, new talent and creative expression have secured the sector’s reputation as the ‘research and development’ branch of the country’s music milieu, where each station is a champion of its local scene, serving as a springboard for bands, presenters and contributors. ‘Other Stations Are Shit’: Student Radio in Aotearoa New Zealand celebrates the contributions of student radio to the arts ecosystem. With full colour images and ephemera, staff profiles and chapters on each of the contemporary stations in addition to student radio whānau, music and its future, this book explores and documents the cultural phenomenon that is student radio.

Ultrawild: An audacious plan to rewild every city on Earth by Steve Mushin $38

Join maverick inventor Steve Mushin as he tackles climate change with an avalanche of mind-bending, scientifically plausible inventions to rewild cities and save the planet. Jump into his brain as he designs habitat-printing robot birds and water-filtering sewer submarines, calculates how far compost cannons can blast seed bombs (over a kilometer), brainstorms biomaterials with scientists and engineers, studies ecosystems and develops a deadly serious plan to transform cities into jungles, rewilding them into carbon-sucking mega-habitats for all species, and as fast as possible. Through marvellously designed and hilarious engineering ideas, Mushin shares his vision for super-high-tech urban rewilding, covering the science of climate change, futuristic materials and foods, bio reactors, soil, forest ecosystems, mechanical flight, solar thermal power and working out just how fast we could actually turn roads into jungles, absorb carbon and reverse climate change.

Before George by Deborah Robertson $30

When Marnya immigrates to New Zealand from South Africa in 1953 with her mother and sister, her mother cuts off Marnya's hair and changes her name to George to hide her identity as a girl. Hours later, their Christmas Eve train plummets into the Whangaehu River and George loses not only her family and name, but also the answers as to why her mother deceived her father and fled their homeland. Now a ward of the state, George finds herself enrolled in a rural school where survival depends on fitting in with a group of boys who think she's strange. Disconnected from everything that once defined who she was, George must reconstruct her identity and come to understand her mother's decisions.

The Trio by Johanna Hedman (translated from Swedish by Kira Josefsson) $26

When Hugo takes a room in the house of one of Stockholm's wealthiest families, he unwittingly invites himself into the lives of people he will be unable to forget: Thora, a beautiful descendant of old money, and her childhood best friend August, who dreams of art. None of them have anything in common, but find themselves irresistibly drawn to each other. Decades later, a young woman shows up on Hugo's door in New York one morning, hoping to stay with him. She introduces herself as the child of Thora and August, and comes carrying questions about her parents that send Hugo reeling back to his youth — to two euphoric summers in Stockholm, and people to whom he is now a stranger.

”The Trio is like the love child of Normal People and Brideshead Revisited. A sublime and elegiac meditation on love, intimacy, freedom and jealousy, it elegantly explores the gulf between our interior lives and the personas we perform — and between ourselves and other people. Hedman's writing (and Josefsson's stunning translation) is staggeringly beautiful. Vivid, effortless, and perceptive to a molecular degree.” —Francesca Reece

The Story of the Brain in 10½ Cells by Richard Wingate $37

There are more than 100 billion brain cells in our heads, and every single one represents a fragment of thought and feeling. And yet each cell is a mystery of beauty, with branching, intricate patterns like shattered glass. Richard Wingate has been scrutinising them for decades, yet he is still moved when he looks at one through a microscope and traces their shape by hand. With absorbing lyricism and clarity, Wingate shows how each type of cell possesses its own personality and history, illustrating a milestone of scientific discovery and exploring the stories of pioneering scientists like Ramon y Cajal and Francis Crick, and capturing their own fascinating shapes and patterns. Discover the ethereal world of the brain with this elegant little book — and find out how we all think and feel.

Wayfinding Leadership: Ground-breaking wisdom for developing leaders by Chellie Spiller, Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, and John Panoho $45

This book presents a new way of leading by looking to traditional waka navigators or wayfinders for the skills and behaviours needed in modern leaders. It takes readers on a journey into wayfinding and leading, discussing principles of wayfinding philosophy, giving examples of how these have been applied in businesses and communities, and providing action points so that readers can practise and reflect on the skills they are learning.

The Faint of Heart by Kerilynn Wilson $30

What would you do if you were the only person left with a heart? The only person left who felt anything at all? Would you give in to the pressure to conform? Or would you protect your heart at all costs? Not that long ago, the Scientist discovered that all sadness, anxiety, and anger disappeared when you removed your heart. And that's all it took. Soon enough, the hospital had lines out the door-even though the procedure numbed the good feelings, too. Everyone did it. Everyone except high school student June. But now the pressure, loneliness, and heartache are mounting, and it's becoming harder and harder to be the only one with a heart. One day, June comes across an abandoned heart in a jar. The heart in the jar intrigues her, it baffles her, and it brings her hope. But the heart also brings her Max, a classmate with a secret of his own. And it may rip June's own heart in two. A memorable graphic novel for teens.

Family of Forest and Fungi | He Tukutuku Toiora by Valetta Sowka; Isobel Joy Te Aho-White, and Hana Natalija Park $24

How did our Māori ancestors use mushrooms? What are some of the astounding ways that fungi can help us? Why do mushrooms glow? Discover the answers to these questions and more in this book for tamariki about the magical world of fungi. Help a child build a natural connection to the taiao by journeying to the forests of Aotearoa and discovering the amazing kingdom of fungi that dwells there!

Dictionary People: The unsung heroes who created the Oxford English Dictionary by Sarah Ogilvie $40

What do three murderers, Karl Marx's daughter and a vegetarian vicar have in common? They all helped create the Oxford English Dictionary. The Oxford English Dictionary has long been associated with elite institutions and Victorian men; its longest-serving editor, James Murray, devoted 36 years to the project, as far as the letter T. But the Dictionary didn't just belong to the experts; it relied on contributions from members of the public. By the time it was finished in 1928 its 414,825 entries had been crowdsourced from a surprising and diverse group of people, from archaeologists and astronomers to murderers, naturists, novelists, pornographers, queer couples, suffragists, vicars and vegetarians. Lexicographer Sarah Ogilvie dives deep into previously untapped archives to tell a people's history of the OED. She traces the lives of thousands of contributors who defined the English language, from the eccentric autodidacts to the family groups who made word-collection their passion.

A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #358th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending, find out which book won the 2023 Booker Prize — and get your seasonal gift-choosing done!

1 December 2023

In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova (translated from Russian by Sasha Dugdale)

The past gets bigger every day, he realised, every day the past gets a day bigger, but the present never gets any bigger, if it has a size at all it stays the same size, every day the present is more overwhelmed by the past, every moment in fact the present more overwhelmed by the past. Perhaps that should be longer rather than bigger, he thought, same difference, he thought, not making sense but you know what I mean, he thought, the present has no duration but the duration of the past swells with every moment, pushing at us, pushing us forward. Anything that exists is opposed by the fact of its existing to anything that might take its existence away, he wrote, the past is determined to go on existing but it can only do this by hijacking the present, he wrote, by casting itself forward and co-opting the present, or trying to, by clutching at us with objects or images or associations or impressions or with what we could call stories, wordstuff, whatever, harpooning us who live only in the present with what we might call memory, the desperation, so to call it, of that which no longer exists except to whatever degree it attaches itself to us now, the desperation to be remembered, to persist, even long after it has gone. Memory is not something we achieve, he wrote, memory is something that is achieved upon us by the past, by something desperate to exist and go on existing, by something carrying us onwards, if there is such a thing as onwards, something long gone, dead moments, ghosts preserving their agency through objects, images, words, impressions, associations, all that, he wrote, coming to the end of his thought. This book, he thought, Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory, is not really about memory at all in the way we usually understand it, it is not about the way an author might go around recalling experiences she had at some previous point in her life, this book is about the way the past forces itself upon us, the way the past forces itself upon us particularly along the channels of family, of ancestry, of blood, so to call it, pushing us before it in such as way that we cannot say if our participation in this process is in accordance with our will or against it, the distinction in any case makes no sense, he thought, there is only the imperative of all particulars not so much to go on existing, despite what I said earlier, though this is certainly the effect, as to oppose, by the very fact of their particularity, any circumstance that would take that existence away. Everything opposes its own extinction, he thought, even me. That again. But the past is vulnerable, too, which is why memory is desperate, a clutching, the past depends upon us to bear its particularity, and we have become adept at fending it off, at replacing it with the stories we tell ourselves about it. The stories we tell about the past are the way we keep the past at bay, the way we keep ourselves from being overwhelmed by this swelling urgent unrelenting past. “There is too much past, and everyone knows it,” writes Stepanova, “The excess oppresses, the force of the surge crashes against the bulwark of any amount of consciousness, it is beyond control and beyond description. So it is driven between banks, simplified, straightened out, chased still-living into the channels of narrative.” When Stepanova’s aunt dies she inherits an apartment full of objects, photographs, letters, journals, documents, and she sets about defusing the awkwardness of this archive’s demands upon her through the application of the tool with which she has proficiency, her writing. Although she writes the stories of her various ancestors and of her various ancestors’ various descendants, she is aware that “this book about my family is not about my family at all, but about something quite different: the way memory works, and what memory wants from me.” Stepanova’s family is unremarkable from a historical point of view, Russian Jews to whom nothing particularly traumatic happened, notwithstanding the possibilities during the twentieth century for all manner of traumatic things to happen to those such as them, and they were not marked out for fame or glory, either, whatever that means, in any case they had no wish to be noticed. History is composed mainly of ordinariness, the non-dramatic predominates, he thought, although there may be notable crises pressing on these particular people, Stepanova’s family for example but the same is true for most people, these notable crises do not actually happen to these particular people. Do not equals did not. The past, as the present, he wrote, was undoubtedly mundane for most people most of the time, and yet they still went on existing, at least resisting their extinction in the most banal of fashions. Is this conveyed in history, though, family or otherwise, he wondered, how does the repetitive uneventfulness of everyday life in the past press upon the present, if at all? Can we appreciate any particularity in the mundanity of the past, he wondered, are we not like the tiny porcelain dolls, the ‘Frozen Charlottes’ that Stepanova collects, produced in vast numbers, flushed out into the world, identical and unremarkable except where the damage caused by their individual histories imbues them with particularity, with character? “Trauma makes us individuals—singly and unambiguously—from the mass product,” Stepanova writes. Who would we be without hardship, if indeed we could be said to be? No idea, not that this was anyway a question for which he had anticipated an answer, he thought. “Memory works on behalf of separation,” Stepanova writes. “It prepares for the break without which the self cannot emerge.” Memory is an exercise of edges, he thought, and all we have are edges, the centre has no shape, there is only empty space. He thought of Alexander Sokurov’s film Russian Ark, and thought how it too piled detail upon detail to reduce the transmission—or to prevent the formation—of ideas about the past, the past piles more and more information upon us in the present, occluding itself in detail, veiling itself, reducing both our understanding and our ability to understand. Stepanova’s words pile up, her metaphors pile up, her sentences pile up, her words ostensibly offer meaning but actually withhold it, or ration it. Although In Memory of Memory is in most ways nothing like Russian Ark, he thought, why did he start this comparison, as with Russian Ark, In Memory of Memory is—entirely appropriately—both fascinating and boring, both too long and never quite reaching a point of satisfaction, the characters both recognisable and uncertain but in any case torn away, at least from us, the actions both deliberate and without any clear rationale or consequence—just like history itself. No residue. No thoughts. No realisations. No salient facts. No wisdom. The past drives us onward, pushes us outward as it inflates.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

Prophet Song is furious in tempo and content. It has knocked me sideways and taken all the other contenders off my best book of the year (and it’s been a year of very good fiction) list by strides. From the knock on the door to the final moment, this novel is breathless, heart-wrenching and brutal. So human, so foreign, yet so real. Eilish is a mother, a wife, a daughter, someone’s sister. She is a microbiologist/desk bound researcher, harrying her children into the car to get to school on time, coaxing her husband, school teacher/union delegate for an answer to a question when he is miles away in his own thoughts, and wondering what her teenage son sees in that girl. She could be your neighbour. Set in an alternative Ireland, nationalism is on the rise. Larry is warned to call off the strike. People are wearing party pins on their lapels. The police are knocking on the door. And then…Larry is arrested. Lawyers can’t make contact with their clients. People are leaving the country. Flags are flying from homes in the street and if you don’t have one, you're against them. You’re a traitor. And then…the rebellion begins and you are at war. Your father’s mind is slipping, your eldest son needs to leave the country, your husband has disappeared, your daughter won’t eat and your baby is teething, while your 12 year-old has become an enigma. And then… food is scarce, bombs are falling, sometimes the electricity comes back on and you bake bread and do the washing on the fast cycle. Prophet Song is an urgent critique on brutality and power; and what it takes to remain in the world even when you are disorientated and disconnected from everything you know and that which holds you safe. The language is bundled together, the sentences almost stepping on each other, as claustrophobic as the situation Eilish finds herself in. This is a brilliant novel that needs to be read for its beauty of language and structure, as well as its haunting content.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch is the winner of the 2023 Booker Prize. Here’s why, according to Esi Edugyan, Chair of the judges: “From that first knock at the door, Prophet Song, forces us out of our complacency as we follow the terrifying plight of a woman seeking to protect her family in an Ireland descending into totalitarianism. We felt unsettled from the start, submerged in – and haunted by – the sustained claustrophobia of Lynch’s powerfully constructed world. He flinches from nothing, depicting the reality of state violence and displacement and offering no easy consolations. Here the sentence is stretched to its limits – Lynch pulls off feats of language that are stunning to witness. He has the heart of a poet, using repetition and recurring motifs to create a visceral reading experience. This is a triumph of emotional storytelling, bracing and brave. With great vividness, Prophet Song captures the social and political anxieties of our current moment. Readers will find it soul-shattering and true, and will not soon forget its warnings.’”

Use our website to choose your seasonal gifts (and books for yourself as well)!

A new book is a promise of good times ahead. Click through for your copies:

Selected Poems by Geoff Cochrane $40

”Geoff Cochrane's is a whole world, rendered in lines at once compressed and open, mysterious and approachable.” —Damien Wilkins

”Over the years, Cochrane's work has been a joy to me, a solace, a proof that art can be made in New Zealand which shows ourselves in new ways.” —Pip Adam

”Would he break your heart, make you chuckle or tear you a new one – one never quite knew. He had this way of creating a moment of meeting that elided everything else, a calm where all our antennae raised as one and you never knew what would come out of his mouth, or his work. —Carl Shuker

(Hardback)

Why Memory Matters: ‘Remembered histories’ and the politics of the past by Rowan Light $18

”Behind the foreground narratives of justification, real or symbolic wounds are stored in the archives of cultural memory.” From curriculum to commemoration to constitutional reform, our society is in the grip of memory, a politics and culture marked by waves of loss, grief, absence and victimhood. Why are certain aspects of the past remembered over others, and why does this matter? In response to this fraught question, historian Rowan Light offers a series of case studies about local debates about history in New Zealand. These provisional judgements of the past illuminate aspects of what it means to remember — and why it matters. (Paperback)

The Forest Brims Over by Maru Ayase (translated from Japanese by Haydn Trowell) $37

Nowatari Rui has long been the subject of her husband's novels, her privacy and identity continually stripped away, and she has come to be seen by society first and foremost as the inspiration for her husband's art. When a decade's worth of frustrations reaches its boiling point, Rui consumes a bowl of seeds, and buds and roots begin to sprout all over her body. Instead of taking her to a hospital, her husband keeps her in an aquaterrarium, set to compose a new novel based on this unsettling experience. But Rui breaks away from her husband by growing into a forest — and in time, she takes over the entire city. (Paperback)

”The effectiveness of The Forest Brims Over lies precisely in Ayase's thorough awareness of the power of fiction: While we may never grow forests out of our bodies, Ayase has enabled us to experience in her words how doing so might just change society for the brighter." —Eric Margolis, The Japan Times

Birdspeak by Arihia Latham $25

”Let me speak as if a bird

Let me speak of you in our reo as if

your memories have wings”

“A call to and from the wild. It is a call for peace and a call to fight. Latham writes from the mud and moonlight; the caves, craters, and lakes of te taiao. Like the digging bird she uses her pen to claw memories out of the earth—the mundane, the joyful, the worried, the violent, the aching memories—before rinsing them in the awa and holding them up, to make us wonder whose they are; hers or ours.” —Becky Manawatu

”There's so much whakapapa to this book with the ancestors, Arihia’s wha nau, the deep pūrākau in it, and all the kaitiaki manu that fly through the pages. Every poem feels like a karanga, or an oriori, or a patere, or even a spell. Reading my tīpuna in her words feels like coming home.” —Ruby Solly

(Paperback)

From Paper to Platform: How tech giants are redefining news and democracy by Merja Myllylahti $18

While global regulators grapple with tech behemoths such as Google and Facebook through evolving laws and regulations, the New Zealand government has held a laissez-faire stance. In From Paper to Platform, prominent New Zealand media scholar, Merja Myllylahti, scrutinises how major digital platforms exert ever-growing influence over news, journalism, our everyday lives, personal rights and access to information. This analysis provides not only insights into the relentless and pervasive impacts these platforms have on our daily experiences, but also delves into their effects on societal structures and the potential perils for our democratic future. (Paperback)

Landfall 246 edited by Lynley Edmeades $30

Presents the winners of the 2023 Landfall Essay Competition; the 2023 Kathleen Grattan Poetry Award ; and the 2023 Caselberg Trust International Poetry Prize. Art: Steven Junil Park, Ann Shelton and Wayne Youle; Non-fiction: Aimee-Jane Anderson-O'Connor, Madeleine Fenn, Eliana Gray and Bronwyn Polaschek; Poetry: Jessica Arcus, Tony Beyer, Victor Billot, Cindy Botha, Danny Bultitude, Marisa Cappetta, Medb Charleton, Janet Charman, Cadence Chung, Brett Cross, Mark Edgecombe, David Eggleton, Rachel Faleatua, Holly Fletcher, Jordan Hamel, Bronte Heron, Gail Ingram, Lynn Jenner, Erik Kennedy, Megan Kitching, Jessica Le Bas, Therese Lloyd, Mary Macpherson, Carolyn McCurdie, Kirstie McKinnon, Frankie McMillan, Pam Morrison, Jilly O'Brien, Jenny Powell, Reihana Robinson, Tim Saunders, Tessa Sinclair Scott, Mackenzie Smith, Elizabeth Smither, Robert Sullivan, Catherine Trundle, Sophia Wilson, Marjory Woodfield, Phoebe Wright; Fiction: Pip Adam, Rebecca Ball, Lucinda Birch, Bret Dukes, Zoë Meager, Petra Nyman, Vincent O'Sullivan, Rebecca Reader, Pip Robertson, Anna Scaife, Kathryn van Beek and Christopher Yee; reviews. (Paperback)

Arita / Table of Contents: Studies in Japanese porcelain by Annina Koivu $110

A beautiful and fascinating large-format book. The art of Japanese porcelain manufacturing began in Arita in 1616. Now, on its 400th anniversary, Arita / Table of Contents charts the unique collaboration between 16 contemporary designers and 10 traditional Japanese potteries as they work to produce 16 highly original, innovative and contemporary ceramic collections rooted in the daily lives of the 21st century. More than 500 illustrations provide a fascinating introduction to the craft and region, while the contemporary collections reveal the unique creative potential of linking ancient and modern masters. (Hardback)

The Things We Live With: Essays on uncertainty by Gemma Nisbet $37

After her father dies of cancer, Gemma Nisbet is inundated with keepsakes connected to his life by family and friends. As she becomes attuned to the ways certain items can evoke specific memories or moments, she begins to ask questions about the relationships between objects and people. Why is it so difficult to discard some artefacts and not others? Does the power exerted by precious things influence the ways we remember the past and perceive the future? As Nisbet considers her father's life and begins to connect his experiences of mental illness with her own, she wonders whether hanging on to 'stuff' is ultimately a source of comfort or concern. The Things We Live With is a collection of essays about how we learn to live with the 'things' handed down in families which we carry throughout our lives — not only material objects, but also grief, memory, anxiety and depression. It's about notions of home and restlessness, inheritance and belonging — and, above all, the ways we tell our stories to ourselves and other people. (Paperback)

A Guided Discovery of Gardening: Knowledge, creativity and joy unearthed by Julia Atkinson-Dunn $50

For some, gardening is a mysterious activity involving muck, unfathomable know-how and physical labour. To others, it is a gateway to creativity, well-being and magic. Julia Atkinson-Dunn knows what it is to stand on both sides of this fence and has channeled her discovery of gardening into a book to aid and inspire others in their own. A Guided Discovery of Gardening is a comprehensive partner in creating a garden, arranged to sweep beginner and progressing gardeners through informative basics to fascinating insights laid bare through Julia's casual, friendly and often personal writing. From introductions to plant types and taking cuttings to valuable tips for home buyers and the curation of seasonally responsive planting. Particularly relevant to temperate regions around the world, rich doses of handy knowledge are intermingled with reflective essays and visual visits to some of her favourite New Zealand gardens, as well as her own. (Flexibound)

Begin Again: The story of how we got here and where we might go — Our human story, so far by Oliver Jeffers $33

Oliver Jeffers shares a history of humanity and his dreams for its future. Where are we going? With his bold, exquisite artwork, Oliver Jeffers starts at the dawn of humankind following people on their journey from then until now, and then offers the reader a challenge: where do we go from here? How can we think about the future of the human race more than our individual lives? How can we save ourselves? How can we change our story? (Hardback)

Roman Stories by Jhumpa Lahiri $40

A man recalls a summer party that awakens an alternative version of himself. A couple haunted by a tragic loss return to seek consolation. An outsider family is pushed out of the block in which they hoped to settle. A set of steps in a Roman neighbourhood connects the daily lives of the city's myriad inhabitants. This is an evocative fresco of Rome, the most alluring character of all: contradictory, in constant transformation and a home to those who know they can't fully belong but choose it anyway. (Paperback)

Open Up by Thomas Morris $33

Five achingly tender, innovative and dazzling stories of (dis)connection. From a child attending his first football match, buoyed by secret magic, and a wincingly humane portrait of adolescence, to the perplexity of grief and loss through the eyes of a seahorse, Thomas Morris seeks to find grace, hope and benevolence in the churning tumult of self-discovery. (Paperback)

”Heart-hurtingly acute, laugh-out-loud funny, and one of the most satisfying collections I've read for years.'“ —Ali Smith

”This brilliant, funny, unsettling book is a work of deep psychological realism and a philosophical inquiry at the same time. Thomas Morris is a master of the contemporary short story, and the stories in this collection are his best.” —Sally Rooney

”That tonic gift, the sense of truth — the sense of transparency that permits us to see imaginary lives more clearly than we see our own. The tonic comes in large doses in Thomas Morris's short-story collection.” —Irish Times

Night Tribe by Peter Butler $25

Twelve-year-old Toby and his sister Millie, fourteen, are tramping the Heaphy Track with their mother when they go off-track to find an old surveyor’s hut their grandfather used. When their mother breaks her leg in a hidden hole the kids set off back to fetch help. They spend some nights alone, hungry and lost. So far, so ordinary, but there is something strange about the cave they’ve camped next to. A little woman emerges and draws them in with the promise of food and shelter. They enter an underground cavern that is deeper than they first thought and where a whole tribe lives. These people believe in natural law, not human law, and have deliberately hidden away from humans believing that here they can survive a total war or pandemic. The kids are intrigued by the techniques this strange people have used to survive but this is tempered by the growing realisation that the Tribe don’t want them to leave. (Paperback)

Here is Hare by Laura Shallcrass $23

An appealing peek-a-book board book with animal characters. (Board book)

Juno Loves Legs by Karl Geary $37

Juno loves Legs. She's loved him since their first encounter at school in Dublin, where she fought the playground bullies for him. He feels brave with her, she feels safe with him, and together they feel invincible, even if the world has other ideas. Driven by defiance and an instinctive feeling for the truth of things, the two find their way from the backstreets and city pubs to its underground parties and squats. Here, on the verge of adulthood, they reach a haven of sorts, a breathing space to begin their real lives. Only Legs's might be taking him somewhere Juno can't follow. Set during the political and social unrest of the 1980s, as families struggled to survive and their children struggled to be free, this beautiful, vivid novel of childhood friendship is about being young, being hurt, being seen and, most of all, being loved. (Paperback)

”Juno Loves Legs will haunt you long after you have read it. In gorgeous, effortless prose, Karl Geary bears witness to those who, like his protagonists, are invisible and voiceless. By boldly confronting the darkness, this novel finds the light.” —Gabriel Byrne

Listen: On music, sound, and us by Michel Faber $40

What is going on inside us when we listen? Michel Faber explores two big questions: how we listen to music and why we listen to music. To answer these he considers biology, age, illness, the notion of 'cool', commerce, the dichotomy between 'good' and 'bad' taste and, through extensive interviews with musicians, unlocks some surprising answers. (Paperback)

Lawrence of Arabia: An in-depth glance at the life of a twentieth-century legend by Ranulph Fiennes $42

Co-opted by the British military, archaeologist and adventurer Thomas Edward Lawrence became involved in the 1916 Arab Revolt, fighting alongside guerilla forces, and made a legendary 300-mile journey through blistering heat. He wore Arab dress, and strongly identified with the people in his adopted lands. By 1918, he had a £20,000 price on his head. (Paperback)

A memorable selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #357th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending, get your copies of the books short-listed for this year’s Booker Prize, and get your seasonal gift-choosing done!

24 November 2023

“Fact is to me a hindrance to memory,” writes the narrator in this remarkable collage of passages evoking the ways in which past experiences have impressed themselves indelibly upon her. The sleepless nights of the title are not so much those of the narrator’s youth, though these are either well documented or implied and so the title is not not about them, but those of her present life, supposedly as “a broken old woman in a squalid nursing home”, waking in the night “to address myself to B. and D. and C.—those whom I dare not ring up until morning and yet must talk to through the night.” As if the narrator is a projection of the author herself, cast forward upon some distorting screen, the ten parts of the book make no distinction between verifiable biographical facts and the efflorescence of stories that arise in the author’s mind as supplementary to those facts, or in substitution for them. Elizabeth the narrator seems almost aware of the precarity of her role, and of her identity as distinct from but overlapping that of the author: “I will do this work of transformed and even distorted memory and lead this life, the one I am leading today.” Hardwick writes mind-woundingly beautiful sentences, many-commaed, building ecstatically, at once patient and careering, towards a point at which pain and beauty, memory and invention, self and other are indistinguishable. Spanning over fifty years, the book, the exquisite narrowness of focus of which is kept immediate by the exclusion of summary, frame or context, records the marks remaining upon the narrator of those persons, events or situations from her past that have not yet been replaced, or not yet been able to be replaced, by the ersatz experiences of stories about those persons, events and situations. “My father…is out, because I can see him only as a character in literature, already recorded.” Hardwick and her narrator are aware that one of the functions of stories is to replace and vitiate experience (“It may be yours, but the house, the furniture, strain toward the universal and it will soon read like a stage direction”), and she/she writes effectively in opposition to this function. Observation brings the narrator too close to what she observes, she becomes those things, is marked by them, passes these marks on to us in sentences full of surprising particularity, resisting the pull towards generalisation, the gravitational pull of cliches, the lazy engines of bad fiction. Many of Hardwick’s passages are unforgettable for an uncomfortable vividness of description—in other words, of awareness—accompanied by a slight consequent irritation, for how else can she—or we—react to such uninvited intensity of experience? Is she, by writing it, defending herself from, for example, her overwhelming awareness of the awful men who share her carriage in the Canadian train journey related in the first part, is she mercilessly inflicting this experience upon us, knowing it will mark us just as surely as if we had had the experience ourselves, or is there a way in which razor-sharp, well-wielded words enable both writer and reader to at once both recognise and somehow overcome the awfulness of others (Rachel Cusk here springs to mind in comparison)? In relating the lives of people encountered in the course of her life, the narrator often withdraws to a position of uncertain agency within the narration, an observatory distance, but surprises us by popping up from time to time when forgotten, sometimes as part of a we of uncertain composition, uncertain, that is, as to whether it includes a historic you that has been addressed by the whole composition without our realising, or whether the other part of we is a he or she, indicating, perhaps, that the narrator has been addressing us all along, after all. All this is secondary, however, to the sentences that enter us like needles: “The present summer now. One too many with the gulls, the cry of small boats on the strain, the soiled sea, the sick calm.”

It’s the time of the year when the New Zealand publishing industry reveals its best and biggest new titles, and many of these are stunning art books. Flora — Celebrating Our Botanical World is one of the gems. This looked stunning even when it was only a cover image and description when it was sold in a few months back, but it’s even better than expected. You can peep inside here. The title is slightly misleading as it made me think that this would only appeal to those who love botanical drawings and precise painterly renditions. In fact, the book draws from an array of disciplines across Te Papa’s collection, including the aforementioned, to textiles, jewellery, photography, furniture, and more. It has a good cross-section of historic and contemporary works, European-inspired as well as Pacifica focuses, and with 400 selections it’s a true treasure box. It’s lovely to look at, as well as being a source of excellent information and expert analysis. The essays are wide-ranging and contextually interesting. Flora is a fine example of cultural history as told through objects, and the texts add that layer that makes this publication a standout. Treat yourself or another art/flora lover.

A new book is a promise of good times ahead. Click through for your copies:

Our Strangers by Lydia Davis $45

Lydia Davis is a virtuoso at detecting the seemingly casual, inconsequential surprises of daily life and pinning them for inspection. In Our Strangers, conversations are overheard and misheard, a special delivery letter is mistaken for a rare white butterfly, toddlers learning to speak identify a ping-pong ball as an egg and mumbled remarks betray a marriage. In the glow of Davis's keen noticing, strangers can become like family and family like strangers. (Hardback)

”This is a writer as mighty as Kafka, as subtle as Flaubert and as epoch-making, in her own way, as Proust.” —Ali Smith

”Davis captures words as a hunter might and uses punctuation like a trap. Davis is a high priestess of the startling, telling detail, a most original and daring mind.” —Colm Toibin

A Shining by Jon Fosse (translated from Nynorsk by Damion Searles) $26

A man starts driving without knowing where he is going. He alternates between turning right and left, and finally he gets stuck at the end of a forest road. Soon it gets dark and starts to snow, but instead of going back to find help, he ventures, foolishly, into the dark forest. Inevitably, the man gets lost, and as he grows cold and tired, he encounters a glowing being amid the obscurity. (Paperback)

”A Shining can be read in many ways: as a realistic monologue; as a fable; as a Christian-inflected allegory; as a nightmare painstakingly recounted the next morning, the horror of the experience still pulsing under the words, though somewhat mitigated by the small daily miracle of daylight. I think the great splendour of Fosse’s fiction is that it so deeply rejects any singular interpretation; as one reads, the story does not sound a clear singular note, but rather becomes a chord with all the many possible interpretations ringing out at once. This refusal to succumb to the solitary, the stark, the simple, the binary – to insist that complicated things like death and God retain their immense mysteries and contradictions – seems, in this increasingly partisan world of ours, a quietly powerful moral stance.’” —Lauren Groff

”Fosse’s prose doesn’t speak so much as witnesses, unfolds, accumulates. It flows like consciousness itself. This is perhaps why A Shining feels so momentous, even at fewer than 50 pages. You never quite know where you’re going. But it doesn’t matter: you want to follow, to move in step with the rhythm of these words.” —Matthew Janney

Hangman by Maya Binyam $40

A man returns home to sub-Saharan Africa after twenty-six years living in exile in America. When he arrives, he finds that he doesn't recognise the country or anyone in it. Thankfully, someone at the airport knows him — a man who calls him brother. As they travel to this man's house, the purpose of his visit comes into focus: he is here to find his real brother, who is dying. In Hangman, Maya Binyam tells the story of this twisted odyssey, and of the phantoms and tricksters, aid workers and taxi drivers, the relatives, riddles and strangers that lead this man along a circuitous path towards the truth. Hangman is a strangely honest story of one man's stubborn search for refuge — in this world and the one that lies beyond it. (Hardback)

”Hangman beckons you into a zone that at first seems as clear, as blank, and as eerily sunny as the pane of a window. Then it traps you there, until you notice the blots, bubbles, and fissures in the glass — and then the frame itself, then the shatter. A clean, sharp, piercing — and deeply political — novel.” —Namwali Serpell

This Plague of Souls by Mike McCormack $40

The long-awaited next novel from the Goldsmiths Prize-winning author of Solar Bones. How do you rebuild the world? How do you put it back together? Nealon returns to his family home in Ireland for the first time in years, only to be greeted by a completely empty house. No heat or light, no furniture, no sign of his wife or child anywhere. It seems the world has forgotten that he even existed. The one exception is a persistent caller on the telephone, someone who seems to know everything about Nealon's life, his recent bother with the law and, more importantly, what has happened to his family. All Nealon needs to do is talk with him. But the more he talks the closer Nealon gets to the same trouble he was in years ago, tangled in the very crimes of which he claims to be innocent. Part roman noir, part metaphysical thriller, This Plague of Souls is a story for these fractured times, dealing with how we might mend the world and the story of a man who would let the world go to hell if he could keep his family together..(Hardback)

”This is the reason Mike McCormack is one of Ireland's best-loved novelists; he is the most modestly brilliant writer we have. His delicate abstractions are woven from the ordinary and domestic — both metaphysical and moving, McCormack's work asks the big questions about our small lives.” —Anne Enright

Forgotten Manuscript by Sergio Chejfec (translated from Spanish by Jeffrey Lawrence) $38

"Could anyone possibly believe that writing doesn't exist? It would be like denying the existence of rain." The perfect green notebook forms the basis for Sergio Chejfec's work, collecting writing, and allowing it to exist in a state of permanent possibility, or, as he says, "The written word is also capable of waiting for the next opportunity to appear and to continue to reveal itself by and for itself." This same notebook is also the jumping off point for this essay, which considers the dimensions of the act of writing (legibility, annotation, facsimile, inscription, typewriter versus word processor versus pen) as a way of thinking, as a record of relative degrees of permanence, and as a performance. From Kafka through Borges, Nabokov, Levrero, Walser, the implications of how we write take on meaning as well worth considering as what we write. This is a love letter to the act of writing as practice, bearing down on all the ways it happens (cleaning typewriter keys, the inevitable drying out of the bottle of wite-out, the difference between Word Perfect and Word) to open up all the ways in which "when we express our thought, it changes." (Paperback)

"It is hard to think of another contemporary writer who, marrying true intellect with simple description of a space, simultaneously covers so little and so much ground.” —Times Literary Supplement

Any Body: A comic compendium of important facts and feelings about our bodies by Katharina von der Gathen and Anke Kuhl $30

An honest, humorous and factual book for children and early teens who want to understand and feel at home with their own bodies. Sometimes we feel uncomfortable in our own skin, sometimes invincible. Katharina von der Gathen’s many years of experience working with children as a sex educator are the basis for this witty encyclopedia covering interesting facts about skin, hair and body functions alongside the questions that may affect us through puberty and beyond—gender identity, beauty, consent, self-confidence, how other people react and relate to us, and how they make us feel. With accessible and warm text, Any Body gently acknowledges common feelings of ambivalence about our bodies. Through showing body diversity and positivity, it encourages acceptance of self and others. The illustrations are relatably funny and include charts, cartoons and more—even a handy page of visual compliments. This compendium is an encouraging starting point for conversations with children navigating puberty and laying the foundations for body acceptance in a straightforward and highly entertaining way.

The Untamed Thread: Slow stitch to sooth the soul and ignite creativity by Fleur Woods $50

The Untamed Thread is the story of Fleur Woods’s journey from corporate world to creative life — woven with generous doses of the practical ways you can bring more creativity into your own life. Taking cues from the natural world we wander through Fleur’s contemporary fibre art practice to encourage and support you to find your own creative path. This inspiring creative guide invites you into Fleur’s art studio, near Upper Moutere. Her practice is as untamed as the New Zealand landscape that inspires her, free of rules, guided by intuition and joy in the process. Together we explore colour, texture, flora, textiles and stitch alongside the magic moments, happy accidents, perfect coincidences and ridiculous randomness of the creative process. Embracing the slow, contemplative nature of stitch we can reconnect our creative spirits to reimagine embroidery as a contemporary tool for mark making. This book wraps you in a warm blanket of nostalgia, grounds you in nature and inspires your senses to allow you to travel down your own creative path gathering all the precious little details meant for you along the way. (Flexibound)

Marigold and Rose: A fiction by Louise Glück $44

The twins, Marigold and Rose, in their first year, begin to piece together the world as they move between Mother’s stories of ‘Long, long ago’ and Father’s ‘Once upon a time’. Impressions, repeated, begin to make sense. The rituals of bathing and burping are experienced differently by each. The story is about beginnings, each of which is an ending of what has come before. There is comedy in the progression, the stages of recognition, and in the ironic anachronisms which keep the babies alert, surprised, prescient and resigned. Charming, resonant, written with Gluck’s characteristic poise and curiosity, Marigold and Rose unfolds as a new kind of creation myth. "Marigold was absorbed in her book; she had gotten as far as the V." So begins Marigold and Rose, Louise Gluck's astonishing chronicle of the first year in the life of twin girls. Imagine a fairy tale that is also a multigenerational saga; a piece for two hands that is also a symphony; a poem that is also, in the spirit of Kafka's ‘The Metamorphosis’, an incandescent act of autobiography.

To the Ice by Thomas Tidholm and Anna-Clara Tidholm $28

Ida, Max and Jack go to the creek one winter’s day. They play on an ice floe then find themselves floating away—all the way to the polar ice, with just a box, a branch and some sandwiches. “You probably don’t think it’s true, and we didn’t either, not even while it was happening.” They find an old hut, meet penguins, see extraordinary things and, after testing their resources in this dramatic land of ice and snow, come home safe at the end of the day. “What shall we say about where we’ve been?” asked Max. “Tell the truth,” I said. “We don’t know.” (Hardback)

Dialogue with a Somnambulist: Stories, essays, and a portrait gallery by Chloe Ardjis $36

Renowned internationally for her lyrically unsettling novels Book of Clouds, Asunder and Sea Monsters, the Mexican writer Chloe Aridjis crosses borders in her writing as much as in life. Now, collected here for the first time, her stories, essays and pen portraits reveal an author as imaginatively at home in the short form as in her longer fiction. Conversations with the presences who dwell on the threshold of waking and reverie, these pieces will stay with you long after the lamps have flickered out. At once fabular and formally innovative, acquainted with reverie and rigorous report, sensitive to the needs of a wider ecology yet familiar with the landscapes of the unconscious, her texts are both dream dispatches and wayward word plays infused with the pleasure and possibilities of language. In this collection of works, we meet a woman guided only by a plastic bag drifting through the streets of Berlin who discovers a nonsense-named bar that is home to papier-mâché monsters and one glass-encased somnambulist. Floating through space, cosmonauts are confronted not only with wonder and astonishment, but tedium and solitude. And in Mexico City, stray dogs animate public spaces, “infusing them with a noble life force.” In her pen portraits, Aridjis turns her eye to expats and outsiders, including artists and writers such as Leonora Carrington, Mavis Gallant, and Beatrice Hastings. (Paperback)

The Sewing Girl’s Tale: A story of crime and consequences in Revolutionary America by John Wood Sweet $40

An account of the first published rape trial in American history and its long, shattering aftermath, revealing how much has changed over two centuries — and how much has not. On a moonless night in the summer of 1793 a crime was committed in the back room of a New York brothel — the kind of crime that even victims usually kept secret. Instead, seventeen-year-old seamstress Lanah Sawyer did what virtually no one in US history had done before: she charged a gentleman with rape. Her accusation sparked a raw courtroom drama and a relentless struggle for vindication that threatened both Lanah's and her assailant's lives. The trial exposed a predatory sexual underworld, sparked riots in the streets, and ignited a vigorous debate about class privilege and sexual double standards. The ongoing conflict attracted the nation's top lawyers, including Alexander Hamilton, and shaped the development of American law. Eventually, Lanah Sawyer did succeed in holding her assailant accountable — but at a terrible cost to herself. (Paperback)

Artichoke to Zucchini: An alphabet of delicious things from around the world by Alice Oehr $30

A is for artichokes and long spears of asparagus. It's for bright, creamy avocados and salty little anchovies… From apple pie to zeppole, and everything in between, Artichoke to Zucchini introduces young readers to fruit, vegetables, and dishes from around the globe. Full of tasty favourites and delicious new discoveries, it's sure to lead to inspiration in the kitchen!

Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting is a favourite with many bookies to win this year’s Booker Prize. (which will be announced in just a few days!). From the author of the excellent Skippy Dies comes a dazzlingly intricate and poignant tragicomedy about family, fortune, and the struggle to be a good man at the end of the world. Exceptionally well-reviewed since its publication, the story is told by the four distinct voices of the Barnes family. Meet Dickie whose car business is going under, but he's out in the woods preparing for the actual end of the world. Meanwhile, his wife Imelda is selling off her jewellery on eBay, their teenage daughter, Cass, is determined to drink her way through the whole thing, and PJ, aged 12, is disappearing into the video game portal and hatching a plan. There’s trouble ahead. Move over Skippy, The Bee is here. This should be on your reading pile this summer.

“Paul Murray’s saga, The Bee Sting, set in the Irish Midlands, brilliantly explores how our secrets and self-deceptions ultimately catch up with us. This family drama, told from multiple perspectives, is at once hilarious and heartbreaking, personal and epic. It’s an addictive read.” —The Booker Judges

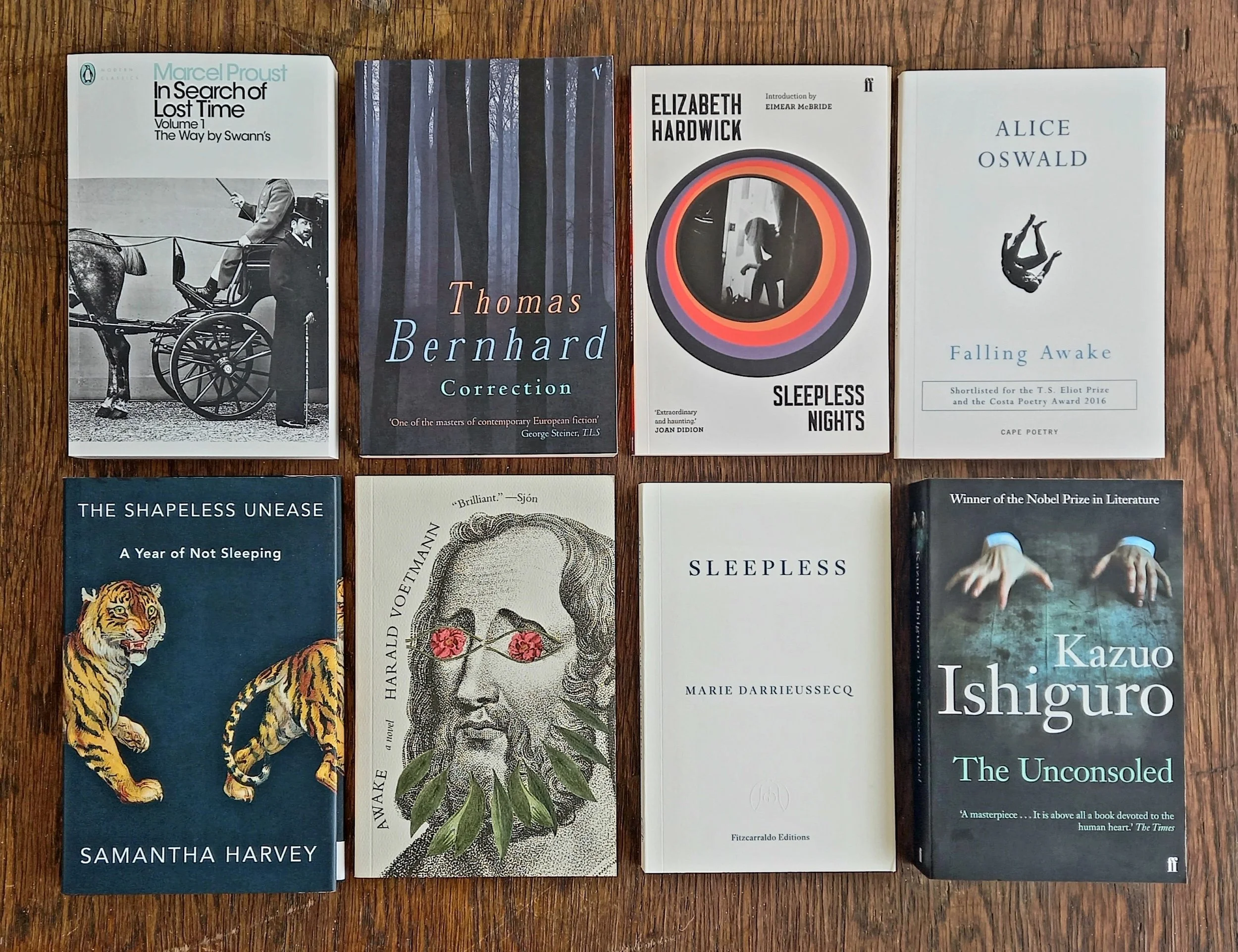

A selection of insomniac books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

GARGOYLES by Thomas Bernhard (translated from German by Richard and Clara Winston)

“The catastrophe begins with getting out of bed.” Gargoyles (first published in 1967 as Verstörung (“Disturbance”)) is the book in which Bernhard laid claim both thematically and stylistically to the particular literary territory developed in all his subsequent novels. In the first part of the book, set entirely within one day, the narrator, a somewhat vapid student accompanying his father, a country doctor, on his rounds, tells us of the sufferings of various patients due to their mental and physical isolation: the wealthy industrialist withdrawn to his dungeon-like hunting lodge to write a book he will never achieve (“’Even though I have destroyed everything I have written up to now,’ he said, ‘I have still made enormous progress.’”), and his sister-companion, the passive victim of his obsessions whom he is obviously and obliviously destroying; the workers systematically strangling the birds in an aviary following the death of their owner; the musical prodigy suffering from a degenerative condition and kept in a cage, tended by his long-suffering sister. The oppressive landscape mirrors the isolation and despair of its inhabitants: we feel isolated, we reach out, we fail to reach others in a meaningful way, our isolation is made more acute. “No human being could continue to exist in such total isolation without doing severe damage to his intellect and psyche.” Bernhard’s nihilistic survey of the inescapable harm suffered and inflicted by continuing to exist is, however, threaded onto the doctor’s round: although the doctor is incapable of ‘saving’ his patients, his compassion as a witness to their anguish mirrors that of the author (whose role is similar). In the second half of the novel, the doctor’s son narrates their arrival at Hochgobernitz, the castle of Prince Saurau, whose breathlessly neurotic rant blots out everything else, delays the doctor’s return home and fills the rest of the book. This desperate monologue is Bernhard suddenly discovering (and swept off his feet by) his full capacities: an obsessively looping railing against existence and all its particulars. At one stage, when the son reports the prince reporting his dream of discovering a manuscript in which his son expresses his intention to destroy the vast Hochgobernitz estate by neglect after his father’s death, the ventriloquism is many layers deep, paranoid and claustrophobic to the point of panic. The prince’s monologue, like so much of Bernhard’s best writing, is riven by ambivalence, undermined (or underscored) by projection and transference, and structured by crazed but irrefutable logic: “‘Among the special abilities I was early able to observe in myself,’ he said, ‘is the ruthlessness to lead anyone through his own brain until he is nauseated by this cerebral mechanism.’” Although the prince’s monologue is stated to be (and clearly is) the position of someone insane, this does not exactly invalidate it: “Inside every human head is the human catastrophe corresponding to this particular head, the prince said. It is not necessary to open up men’s heads in order to know that there is nothing inside them but a human catastrophe. ‘Without this human catastrophe, man does not exist at all.'”

A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #356th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending, get your copies of the books short-listed for this year’s Booker Prize, and choose some other books as well!

17 November 2023