Read our latest NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending (and what Stella has been doing with some quinces).

19 April 2024

Read our latest NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending (and what Stella has been doing with some quinces).

19 April 2024

I thought for a while that horse racing was a sort of sport, and I wondered if there were other sports in which the people participating in them were relatively unknown, horse racing being done in the name of the horses, after all, not in the name of the jockeys, whereas cycle racing is done in the names of the cyclists not in the name of their bicycles, and then I realised that horseracing is not a sport at all, but a kind of competition more akin to marbles, a competition of ownership, in which the jockeys are just what make the horses go, the jockeys are the augmentation of the prowess of the horses with the will of their owners, nothing more, implants, marginal figures along with the other unknown persons whose collective efforts both enable and are obscured by the horses that they serve. But this marginalisation, together with the peripatetic nature of these professions, makes the contained human society of the racecourse backstretch such a fascinating and, for want of a better word, such a human one. In small worlds what would otherwise be small is writ large, and what would otherwise be unnoticed is made clear. Kathryn Scalan’s wholly remarkable novel Kick the Latch is ostensibly the edited-down text of the Sonia half of a series of interviews between Scanlan and a longtime horse trainer (and subsequently prison guard and later bric-a-brac dealer) named Sonia, conducted between 2018 and 2021. Certainly there is a pellucid quality to these first-person accounts, the voice and language of Sonia are strongly delineated and very appealing to read, and the insights gleaned from them into the life of their narrator, from her hard-scrabble girlhood to her hard-scrabble but colourful life around the racetrack and beyond, are entirely compelling. In these twelve sets of titled anecdotes, Scanlan has succeeded in making herself entirely invisible (the text’s invisible but vital jockey), which shows invisibility to be a cardinal virtue for an author or an editor — and it is uncertain which of these labels applies itself most suitably to Scanlan’s achievement in making this book. Perhaps all good writing is primarily editing, primarily on the part of the writer themselves (and secondarily by any subsequent editor). Anyone can generate any amount of text; it is only the ruthless and careful editing of this text (before and after it is actually written down), the trimming and tightening of text, the removal of all but the essential details and the tuning of the grammatical mechanisms of the text, that produces something worth reading. The virtues of literature are primarily negative. I first came across Scanlan with her first book, the poignant and beautiful Aug 9—Fog, which was made by ‘editing down’ a stranger’s diary found at an estate sale into a small book of universal resonance. Kick the Latch could be said to be an extension of the same project: an applied rigour and unsparing humility by Scanlan that makes something that would otherwise be ordinary and unnoticed — found experiences from unimportant lives, as are all of our lives unimportant — into something so sharp and clear that it touches the reader deeply. What more could we want from literature than this?

I was beguiled initially by the cover of this book, then the title, then the recommendation by Megan Hunter (author of The Harpy and The End We Start From), and after that the description. Forty women in an underground bunker with no clear understanding of their captivity. Why are they there? What was their life before? And as the years pass, what purpose do the guards, or those who employ the guards, have for them? The narrator of this story is a young woman—captured as a very young child—who knows no past: her life is the bunker. The women she lives with tolerate her but have little to do with her and hardly converse with her. She is not one of them. They have murky memories of being wives, mothers, sisters, workers. They know something catastrophic happened but can not remember what. The Child (nameless) is seen as other, not like them, not from the same place as them. The Child has been passing the days and the years in acceptance, knowing nothing else, but her burgeoning sexuality and her awareness of life beyond the cage (she starts to watch the guards, one young man in particular), limited as it is to this stark underground environment, also triggers an awakeness. She begins to think, to wonder and ask questions. As she counts the time by listening to her heartbeats and wins the trust of a woman in the group, The Child’s observations, not clouded by memories, are pure and exacting. We, as readers, are no closer to understanding the dilemma the women find themselves in, and like them are mystified by the situation. Our view is only that of The Child and what she gleans from the women—their past lives that are words that have little meaning to her, whether that is nature (a flower), culture (music) or social structures (work, relationships)—this world known as Earth is a foreign landscape to her. When the sirens go off one day, the guards abandon their positions and leave. Fortunately for the women, this happens just as they have opened the hatch for food delivery. The young woman climbs through and retrieves a set of keys that have been dropped in the panic. The women are free, but what awaits them is in many ways is another prison. Following the steps to the surface takes them to a barren plain with nothing else in sight. What is this place? Is it Earth? And where are the other people? Will they find their families or partners or other humans? The guards have disappeared within minutes—we never are given any clues to where they have gone—have they vapourised? Have they left in swift and silent aircraft? The women gather supplies, of which there are plenty, and begin to walk. I Who Have Never Known Men is a feminist dystopia in the likes of The Handmaid’s Tale or The Book of the Unnamed Midwife but is more silent, more internal and both frustrating and compelling. I found myself completely captivated by the mystery of this place and the certainty of the young woman. The exploration of humanity and its ability to hope and love within what we would consider a bleak environment, and the magnitude of one woman to gather these women to her and cherish them as they age is exceedingly tender. The introduction by Sophie MacKintosh ( author of The Water Cure and Cursed Bread), which I recommend reading after rather than before, adds another layer of meaning to the novel. I Who Have Never Known Men is haunting and memorable—a philosophical treatise on what it is to be alone and to be lonely, and what freedom truly is.

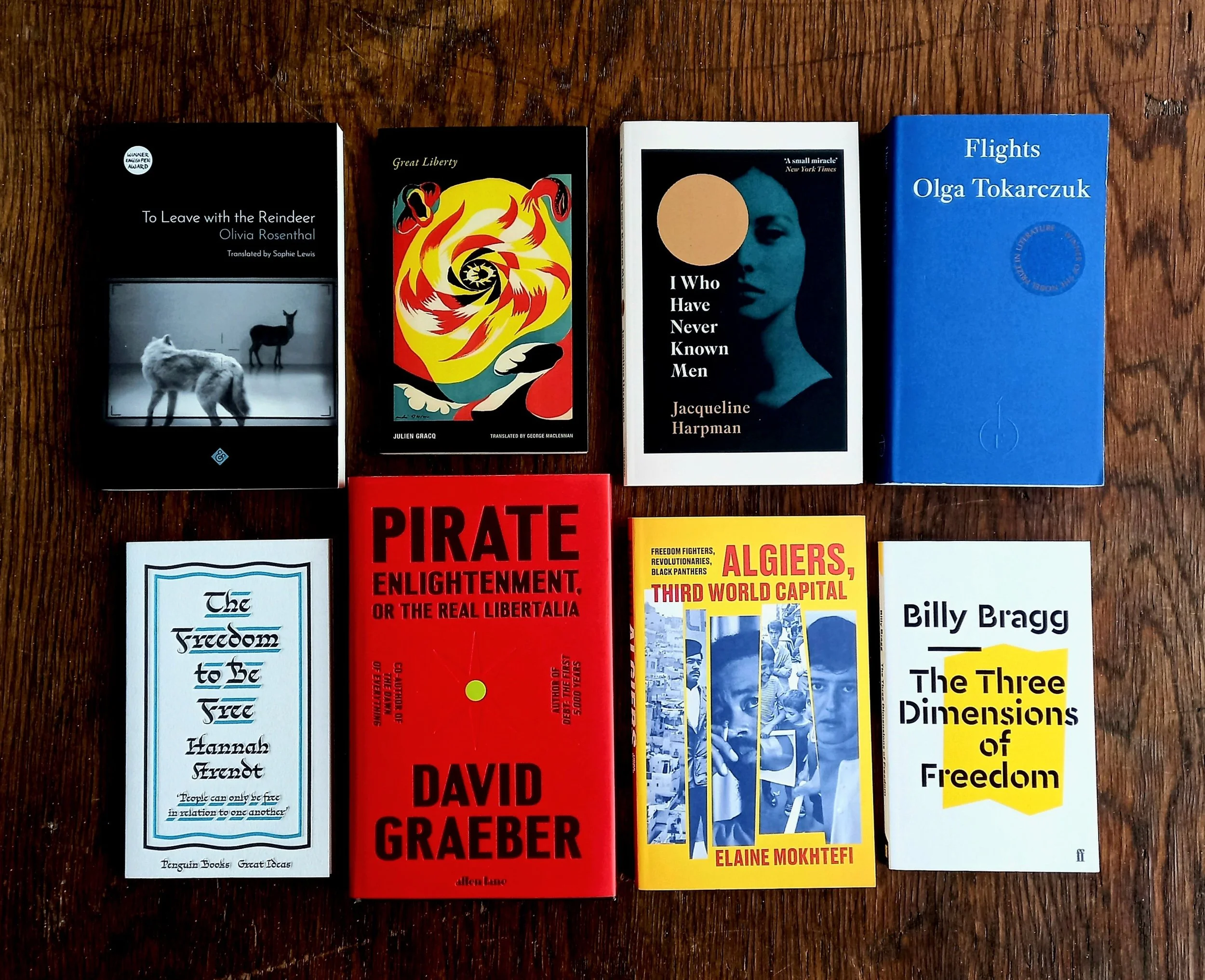

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

The Three Dimensions of Freedom

The abattoir has an unspoken centrality to Brazilian rural culture, just as it has in New Zealand. In Ana Paula Maia’s superbly, sparely written novel, set in a slaughterhouse in an impoverished and isolated corner of Brazil, the established tension between repetitive killing and the unthinking acceptance functionally necessary for its continuance — for both humans and cattle — is unbalanced by something seemingly beyond the contained and ritualised world of rural meat production. What is it that is driving the men, and the animals, to madness and murder?

New arrivals — just out of the carton! Click through to our website to place your orders.

100 Years of Darkness: Poems about films and film music by Bill Direen $30

The 76 poems of 100 Years of Darkness pays homage to a century of cinema and its music. The films are drawn from Japan, U.S.A., France, Germany, Russia/Ukraine, Vietnam, Sweden, Italy, Spain, New Zealand, Lebanon and other places. Since only a few of them have been released in all countries, the chosen films are itemised by means of a detailed index of sources at the close. This makes it easy for film and music lovers to find the directors and years of first appearance — to eventually see the films for themselves. The book’s cover design represents aspect ratios used worldwide between 1888 and the present.

The Sky is Falling by Lorenza Mazzetti (translated from Italian by Livia Franchini) $38

First published in 1961, Lorenza Mazzetti's The Sky is Falling (Il cielo cade) is an impressionistic, idiosyncratic, and uniquely funny look at the writer's childhood after she and her sister are sent to live with their Jewish relatives following the death of their parents. Bright and bucolic, vivid and mournful, and brimming with saints, martyrdom, ideals, wrong-doing and self-imposed torments, the novel describes the loss of innocence and family under the Fascist regime in Italy during World War II through the eyes of Mazzetti's fictional alter ego, Penny, in sharp, witty (and sometimes petulant) prose. First translated into English as The Sky Falls by Marguerite Waldman in 1962, with several pages missing due to censorship, the novel has been out of print in the anglophone world for many years. Livia Franchini's beautiful new translation carries over the playfulness and perverse naivete of the original Italian. Recommended!

Amma by Saraid de Silva $38

Singapore, 1951. When Josephina is a girl, her parents lock her in a room with the father of the boy to whom she's betrothed. What happens next will determine the course of her life for generations to come. New Zealand, 1984. Josephina and her family leave Sri Lanka for New Zealand. But their new home is not what they expected, and for the children, Sithara and Suri, a sudden and shocking event changes everything. London, 2018. Arriving on her uncle Suri's doorstep, jetlagged and heartbroken, Annie has no idea what to expect — all she knows is that Suri was cast out by his amma for being gay, like she is. Moving between cities and generations, Amma follows three women on very different paths, against a backdrop of shifting cultures. As circumstance and misunderstanding force them apart, it will take the most profound love to knit them back together before it's too late.

Ticknor by Sheila Heti $40

On a cold, rainy night, an aging bachelor named George Ticknor prepares to visit his childhood friend Prescott, now one of the leading intellectual lights of their generation. Reviewing a life of petty humiliations, and his friend's brilliant career, Ticknor sets out for the dinner party-a party at which he'd just as soon never arrive. Distantly inspired by the real-life friendship between the historian William Hickling Prescott and his biographer, Ticknor is a witty, fantastical study in resentment. It recalls such modern masterpieces of obsession as Thomas Bernhard's The Loser and Nicholson Baker's The Mezzanine and, when first published in 2006, announced the arrival of a charming and original novelist, one whose novels and other writings have earned her a passionate international following.

"A perceptive act of ventriloquism, Ticknor rewards thought and rereading, and offers a finely cadenced voice, intelligence and moody beauty." —The Globe and Mail

"Confoundedly strange and fascinating." —Quill & Quire

The Extinction of Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft $40

Eight translators arrive at a house in a primeval Polish forest on the border of Belarus. It belongs to the world-renowned author Irena Rey, and they are there to translate her magnum opus, Gray Eminence. But within days of their arrival, Irena disappears without a trace. The translators, who hail from eight different countries but share the same reverence for their beloved author, begin to investigate where she may have gone while proceeding with work on her masterpiece. They explore this ancient wooded refuge with its intoxicating slime molds and lichens, and study her exotic belongings and layered texts for clues. But doing so reveals secrets - and deceptions - of Irena Rey's that they are utterly unprepared for. Forced to face their differences as they grow increasingly paranoid in this fever dream of isolation and obsession, soon the translators are tangled up in a web of rivalries and desire, threatening not only their work but the fate of their beloved author herself. This hilarious, thought-provoking debut by award-winning translator and author Jennifer Croft is a brilliant examination of art, celebrity, the natural world, and the power of language. It is an unforgettable, unputdownable adventure with a small but global cast of characters shaken by the shocks of love, destruction, and creation in one of Europe's last great wildernesses.

”Croft writes with an extraordinary intensity.” —Olga Tokarczuk

”Mischievous and intellectually provocative, The Extinction of Irena Rey asks thrilling questions about the wilderness of language, the life of the forest, and the feral ambitions and failings of artists.“ —Megha Majumdar

”Generous and strange, funny and disconcerting, The Extinction of Irena Rey is a playground for the mind and an entrancing celebration of the sociality of reading, writing, and translation written by a master practitioner of all three.” —Alexandra Kleeman

Six-Legged Ghosts: The insects of Aotearoa by Lily Duval $55

Why isn’t Aotearoa famous for its insects? We have wētā that can survive being frozen, weevils with ‘snouts’ almost as long as their bodies, and the world’s only alpine cicadas. There is mounting evidence that insect numbers are plummeting all over the world. But the insect apocalypse isn’t just a faraway problem – it’s also happening here in Aotearoa. In recent years, we have lost a number of our native insects to extinction and many more are teetering on the brink. Without insects, the world is in trouble. Insects are our pollinators, waste removers and ecosystem engineers – they are vital for a healthy planet. So why don’t more people care about the fate of the tiny but mighty six- legged beings that shape our world? Richly illustrated, and including more than 100 original paintings by the author, Six-legged Ghosts: The insects of Aotearoa examines the art, language, stories and science of insects in Aotearoa and around the world. From te ao Māori to the medieval art world, from museum displays to stories of the insect apocalypse, extinction and conservation, Lily Duval explores the lives of insects not only in Aotearoa’s natural environments, but in our cultures and histories as well.

Talia by Isla Huia (Te Āti Haunui a-Pāpārangi, Uenuku) $30

Short-listed for the 2024 Ockham Book Awards, The poems in Talia are a critique of hometowns, an analysis of whakapapa, and a reclamation of tongue. It is an ode to the earth the poet stands on, and to a sister she lost to the skies. It is a manifesto for a future full of aunties and islands and light.

”This is a collection so movingly steeped in aroha, in the power and reach and traffic of love. It is a poetry collection to put on repeat, to lose and find your way in. I love it.” —Paula Green

Ninth Street Women — Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five painters and the movement that changed modern art by Mary Gabriel $40

Set amid the most turbulent social and political period of modern times, Ninth Street Women is the impassioned, wild, sometimes tragic, always exhilarating chronicle of five women who dared to enter the male-dominated world of twentieth-century abstract painting — not as muses but as artists. From their cold-water lofts, where they worked, drank, fought, and loved, these pioneers burst open the door to the art world for themselves and countless others to come. Gutsy and indomitable, Lee Krasner was a hell-raising leader among artists long before she became part of the modern art world's first celebrity couple by marrying Jackson Pollock. Elaine de Kooning, whose brilliant mind and peerless charm made her the emotional center of the New York School, used her work and words to build a bridge between the avant-garde and a public that scorned abstract art as a hoax. Grace Hartigan fearlessly abandoned life as a New Jersey housewife and mother to achieve stardom as one of the boldest painters of her generation. Joan Mitchell, whose notoriously tough exterior shielded a vulnerable artist within, escaped a privileged but emotionally damaging Chicago childhood to translate her fierce vision into magnificent canvases. And Helen Frankenthaler, the beautiful daughter of a prominent New York family, chose the difficult path of the creative life. Her gamble paid off: At twenty-three she created a work so original it launched a new school of painting. These women changed American art and society, tearing up the prevailing social code and replacing it with a doctrine of liberation.

A Philosophy of Walking by Frédéric Gros $25

By walking, you escape from the very idea of identity, the temptation to be someone, to have a name and a history ... The freedom in walking lies in not being anyone; for the walking body has no history, it is just an eddy in the stream of immemorial life. In A Philosophy of Walking, a bestseller in France, leading thinker Frederic Gros charts the many different ways we get from A to B-the pilgrimage, the promenade, the protest march, the nature ramble-and reveals what they say about us. Gros draws attention to other thinkers who also saw walking as something central to their practice. On his travels he ponders Thoreau's eager seclusion in Walden Woods; the reason Rimbaud walked in a fury, while Nerval rambled to cure his melancholy. He shows us how Rousseau walked in order to think, while Nietzsche wandered the mountainside to write. In contrast, Kant marched through his hometown every day, exactly at the same hour, to escape the compulsion of thought. Brilliant and erudite, A Philosophy of Walking is an entertaining and insightful manifesto for putting one foot in front of the other. New edition.

Shakespeare’s Sisters: Four women who wrote the Renaissance by Ramie Targoff $38

In an innovative and engaging narrative of everyday life in Shakespeare's England, Ramie Targoff carries us from the sumptuous coronation of Queen Elizabeth in the mid-16th century into the private lives of four women writers working at a time when women were legally the property of men. Some readers may have heard of Mary Sidney, accomplished poet and sister of the famous Sir Philip Sidney, but few will have heard of Aemilia Lanyer, the first woman in the 17th century to publish a book of original poetry - a feminist take on the crucifixion, or Elizabeth Cary, who published the first original play by a woman — about the plight of the Jewish princess Mariam. Then there was Anne Clifford, a lifelong diarist, who fought for decades against a patriarchy that tried to rob her of her land in one of England's most infamous inheritance battles.

Champ by Payam Ebrahimi and Reza Dalvand $35

Abtin is nothing like the rest of his family. The Moleskis are fiercely competitive sports champions, and they expect Abtin to become a great athlete too. But Abtin is a reader, an artist, and has his own way of doing things. Despite his family's best efforts, Abtin remains stubbornly himself. Wanting his family to be proud of him, he comes up with a plan to make them happy: a plan that doesn't go quite as expected.

Heresy: Jesus Christ and the other Sons of God by Catherine Nixey $40

“In the beginning was the Word,” says the Gospel of John. This sentence — and the words of all four gospels — is central to the teachings of the Christian church and has shaped Western art, literature and language, and the Western mind. Yet in the years after the death of Christ there was not merely one word, nor any consensus as to who Jesus was or why he had mattered. There were many different Jesuses, among them the aggressive Jesus who scorned his parents and crippled those who opposed him, the Jesus who sold his twin into slavery and the Jesus who had someone crucified in his stead. Moreover, in the early years of the first millennium there were many other saviours, many sons of gods who healed the sick and cured the lame. But as Christianity spread, they were pronounced unacceptable — even heretical — and they faded from view. Now, in Heretic, Catherine Nixey tells their extraordinary story, one of contingency, chance and plurality. It is a story about what might have been.

"How on earth could an ancient Greek word meaning 'choice' come to be used exclusively negatively to mean heresy? Catherine Nixey, expert in the darkening age of Late Antique religiosity, has all the answers, brilliantly resurrecting a teeming plurality of non-canonical, non-orthodox, and above all allegedly non-Christian ideas and practices with cool intellectual clarity and vivid literary skill.” —Paul Cartledge

Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s hidden histories by Amitav Ghosh $38

When Amitav Ghosh began the research for his monumental cycle of novels, ‘The Ibis Trilogy’, ten years ago, he was startled to find how the lives of the 19th century sailors and soldiers he wrote of were dictated not only by the currents of the Indian Ocean, but also by the precious commodity carried in enormous quantities on those currents: opium. Most surprising at all, however, was the discovery that his own identity and family history was swept up in the story. Smoke and Ashes is at once a travelogue, memoir and an essay in history, drawing on decades of archival research. In it, Ghosh traces the transformative effect the opium trade had on Britain, India, and China, as well as the world at large. The trade was engineered by the British Empire, which exported Indian opium to sell to China and redress their great trade imbalance, and its revenues were essential to the Empire's financial survival. Yet tracing the profits further, Ghosh finds opium at the origins of some of the world's biggest corporations, of America's most powerful families and prestigious institutions (from the Astors and Coolidges to the Ivy League), and of contemporary globalism itself. Moving between horticultural histories, the mythologies of capitalism, and the social and cultural repercussions of colonialism, Ghosh reveals the role that one small plant had in the making of our world, now teetering on the edge of catastrophe.

”Ghosh has reinvented himself as a superlative commodity historian. In his new role, he has surpassed many seasoned historians in his ability to synthesise a wealth of research with remarkable intellectual clarity and suggestive simplicity. There's a quietly subversive element to Smoke and Ashes for which Ghosh deserves to be commended.” —The Times

Māori Made Easy Pocket Guide: Essential greetings, phrases and tikanga for every day by Scotty Morrison $24

This little book that really will fit into your pocket is your guide to using te reo Māori in every day situations, from introductions to conversations, online and in person. Carry the essentials with you, and develop confidence in: * Basic pronunciation * Greetings * Dates and times * Pepeha * Whakataukī * Karakia * Iwi names * and much more.

All Through the Night: Why our lives depend on dark skies by Dani Robertson $40

Why darkness is so important – to plants, to animals, and to ourselves – and why we must protect it all costs. Darkness is the first thing we know in our human existence. Safe and warm inside the bubble of the womb, we are comfortable in that embracing dark. But as soon as we are bought into the light, we learn to fear the dark. Why? Some 99 per cent of Western Europeans live under light polluted skies, but what is this doing to our health? Our wellbeing? Our connection to the cycles of nature? Our wildlife, too, has been cast into the harsh glare of our light addiction, with devastating impacts.

In this book Dani shares with you the excitement and adventure she has found when everyone else is tucked up in bed. She explores constellations and cultures, enjoys environmental escapades, all whilst learning why we are addicted to light and why it is ruining our lives. She’ll show you why the darkness is so important and why we must protect it all costs.

Quince Philosopher

A kava bowl of quinces had been glowing beautifully in the living room, but now it was time to act. Recently I found some ancient jelly in the cupboard. Quince circa 2002. It looked fine, as in no mildewy mouldy stuff, but it’s incredibly dark red,in fact probably black. Consuming this doesn’t seem likely, but it did remind me how delcious quince jelly is. Saturday it rained. Perfect for hot work at the stove. Reaching for Kylee Newton’s The Modern Preserver revealed not only a lovely jelly recipe (Quince and Cardamom), but also Membrillo (paste). I had enough quinces for both, so grabbed a sharpish knife and some muscle power, and began. This was a two-day job, as the recipe required an overnight straining for the jelly liquid. (In fact, this wasn’t necessary, as most of the juice drained through almost at once.)

While the first batch was cooking, I flexed my muscles for the peeling and coring of the remaining quinces. This is when you need to focus on the end result! We once made Quince Paste for Christmas gifting and I remember it, rightly or wrongly, being quite a process. This Membrillo recipe included lemion peel and vanilla and smelt wonderful smimmering away gently. The quinces changed colour to a beautiful rich yellow, ready to whizz into that soft puree. And then it was back on the stove! And plenty of stirring. Making this again, I would cook the quinces for a bit longer in each stage. I stuck with the recipe timing, but whether it was the type of quince or our sluggish element, I didn’t quite capture the glowing red of the jelly as you will see below. Anyway the fruit was soft and the fragrance wonderful, and ready for the final slow slow bake in the oven. The tempature instruction being: your lowest possible setting!

Here I broke the rules a little, and spooned my puree into small paper cases, thinking they would make good serving sizes. And half a round is perfect for snack! (That lovely plate is made by Esther. @ceramicsbyesther). And the Membrillo is delicous. Definitely worth the effort.

And so to the next day’s work! The jam pan (inherited from my nana) came out of the bottom cupboard to do its hard work. More boiling and stirring! It required a stool nearby for resting. While the recipe indicated 20 minutes of gentle boiling (once the liquid had come to the boil), I almost doubled the time (possibly the result of our timid element) keeping a close eye on that terrible disappoinment called burning! (It didn’t burn.) I wanted a firm jelly, but not rubbery, and watching closely, testing frequently, and noting the changes in consistancy and colour, was worthwhile. I like this recipe. The cardamom is subtle and the small amount of lemon juice takes the edge off the sweetness, but not by much. The colour of quince jelly is divine. A glowingly satisfying result.

Postscript: We did eat dinner. It was a yellow theme. Pumpkin season. Hurrah for $4 Crowns!

This tasty dish from one of my favourite Ottolenghi’s: Flavour. Cinnamon, star anise, a little heat with chilli and black pepper, pumpkin and onions roasted, on a bed of tomato-infused couscous and layered with spinach from the garden. Perfect for autumn.

Every purchase of a cookbook from VOLUME during April goes in the draw to win a copy of Portico by Leah Koenig.

Read our latest newsletter

12 April 2024

Wherever humans gather they begin to do each other harm. The size of human gathering that optimises this harm is called, in England, a village. Neither small enough for differences to be accommodated nor large enough for them to be ignored, a village allows its inhabitants full exercise of their capacities for intolerance, for suspicion, for collective cruelty. In Max Porter’s poetic and affecting short novel Lanny, a couple move to one such village with their highly imaginative son, Lanny. The first part of the book is told in the alternating voices of the parents and of Pete, the elderly artist from whom Lanny receives art lessons. Lanny’s mother is trying to pull out of a period of depression, writing a crime thriller, and his father continues to commute to London, both a presence and an absence in the lives of the other members of his family. We see the ethereal Lanny through their eyes, but it is perhaps Pete who identifies most with his original ways of thinking and original ways of seeing. Narrated in the voices of these characters, the text provides access only to what they are prepared to acknowledge, leaving uncertain spaces. There is a fourth ‘voice’ in this first part of the book, that of ‘Dead Papa Toothwort’, a personification of a force of nature suppressed in modern life, a principle of decay and regrowth, assailing social fixity and seen primarily in its negative aspect as a force of destruction or death. From beneath the structures of stultification that comprises, to Porter, English village life, even Englishness itself, from the land, from growing and rotting things, from nature, comes the force that will bring down those structures. The first part of the book is saturated with ominous feeling as Toothwort approaches and wanders the village. As with the plant from which he gets his name, Toothwort is parasitic: like death, he has no form but the form he borrows, no words but the words he borrows. “He does the voices,” writes Porter, after Shakespeare, referring to himself, perhaps, as much as to his character. The Toothwort sections are comprised largely of odd snippets and freighted phrases such as are overheard in passing the conversations of others, lines often arranged on the page in a typographically eccentric way like the verbal detritus they are. Just as Toothwort uses phrases gleaned from the village to remake into his purposes, so does the author. A text always contains the ominous presence of the author’s intention, the author as a fateful presence, constructing the sentences but at the same time drawing them towards their death. Toothwort appears in the guise of ordinary things because the ordinary really is full of horror and the kind of undoing that he represents. He is “reckoning with the terrible joke of the flesh and the rubbery links between life and death.” Toothwort wanders the village and ‘chooses’ Lanny, the being most like himself. The second part of the book is told in myriad unattributed but distinct voices of people in the village, along with Lanny’s parents, Pete, and people involved in the search for Lanny after he disappears. These muttered, declaimed, gossipped or published passages demonstrate how, after a crisis is not quickly resolved, the worst aspects of people often come to the fore and people speak and act their prejudices, suspicions, jealousies and resentments, using them to vault to conclusions that relieve their uncertainty. Pete is beaten, Lanny’s mother slurred, anyone with a difference resented or suspected. The village builds itself into an unhealthy state of what could only be called excitement. These ‘external’ snippets are uncomfortable. The reader, like the villagers, is a voyeur, implicated in the crisis that exists for and because of those - villagers and readers - who observe and shape the crisis. We jump to conclusions and reveal our prejudices as do the villagers. We resent the author who reveals us to ourselves as the stories of the voyeurs swamp the facts (or, rather, the absence of facts). The third part of the book begins in the most internal of modes: the dreams of those closest to Lanny (his parents and Pete), dreams of Toothwort-catalysed possible Lannys and possible fates for Lanny. The sequence resolves into a dream of Lanny’s mother, of how Toothwort reveals Lanny to her in this dream, of how she wakes, “breathes in the flesh particles of generations of villagers before her and it tastes like mould and wet tweed,” and finds him, and of what comes after. Lanny’s mother is “caught between what is real and what is not,” however, and I can’t excise my suspicion that the entire sequence, including its resolution, is her dream or desire, a ‘possible’ but not necessarily ‘true’ story, a trajectory in her mind, a disengagement from other, external, possibly more ‘true’ stories - but isn’t fiction always like this? This is a remarkable book. Porter has the uncanny ability to evoke the ordinary and then make it reveal a certain beauty and depth and horror just as it slips away from our ability to hold it in our minds.

What is it about cooler months that make puzzling so appealing? I enjoy all sorts of puzzles, of both the word and number variety, but love the challenge of a jigsaw puzzle with its bonus of a visually compelling end result. So it's ideal to have a birthday in March and to receive a fresh jigsaw in the time for autumnal rains and darker nights. I'm loving The World of the Brontës. Before even finding those sides and corners I had to read the little story of the Brontës and get the lowdown on the family, the many characters, the houses and the pets which are dotted throughout the puzzle to find. Centre stage of this puzzle is the great and terrifying fire at Thornfield Hall depicted by lively swirling flames. There's the moody moor for Catherine's ghost in a colour palette of bruised purples and in a surreal sky of pinks and yellows the world of picture books and fantastical land of Gondal. Having read The Tenant of Wildfell Hall last year (aloud), I was pleased to see the inclusion of the long-suffering, but defiant, Helen Huntingdon with her young son included, even if at her feet are her painting materials cast asunder. And of course, there are the Brontës themselves, Maria and Elizabeth, Charlotte, Bramwell, Emily and Anne. The houses are both the real and the imagined, and the piecing together of these similar looking bricks and stonework is a pleasurable exercise with small clues in the window surrounds, roof structure and tile colours. In other words, not obvious, but neither impossible. The illustrator Eleanor Taylor has included so many wonderful details from the Brontë sisters' ouvres and cleverly melded these many elements into a cohesive image. Great fun and a compelling distraction.

There were some exciting arrivals this week. Click through to our website to secure your copies.

Marlow’s Dream: Joseph Conrad in Antipodean Ports by Martin Edmond $45

Before Joseph Conrad’s writing career was established in 1899 with the serialised publication of Heart of Darkness, he was a merchant seafarer and eventually a shipmaster of vessels that regularly sailed between Europe and its antipodes, with several visits to Australia and New Zealand, stopping at numerous other ports along the way. In Marlow's Dream, Martin Edmond shows in vivid detail how Conrad both collected and began to arrange the tales that would later appear in his fiction during these voyages. Intertwining Conrad's biography with his own, Edmond demonstrates how Conrad's stories were lifted straight out of his experiences as an itinerant mariner who had spent many days in antipodean ports between 1878-93.

"No writer has more to tell us about our oceanic past and its human dramas than Joseph Conrad. Now Martin Edmond adds something new to Conrad's world, a hard thing to do. By placing Conrad among the Antipodean people he knew and the Antipodean ports he frequented as a sailor, the fictions become more vivid, more real, while the raffish cosmopolitanism of old Australasian port life becomes less remote. We are closer both to Conrad and the past. A marvelous achievement!" —Simon During (University of Queensland)

"Edmond wants to understand Conrad's fiction from the inside, and he wants to do this in a way that will make sense to an audience wider than the limited readership of academic literary criticism." —Andrew Dean (Deakin University)

Ash by Louise Wallace $30

Thea lives under a mountain — one that’s ready to blow. A vet at a mid-sized rural practice, she has been called back during maternity leave and is coping – just – with the juggle of meetings, mealtimes, farm visits, her boss’s search for legal loopholes and the constant care of her much-loved children, Eli and Lucy. But something is shifting in Thea – something is burning. Or is it that she is becoming aware, for the first time, of the bright, hot core at her centre? Then comes an urgent call. Ingeniously layered, Ash is a story about reckoning with one’s rage and finding marvels in the midst of chaos.

”I have not felt this seen by a book, ever. Ash worked through me like a drug: I will be going back again and again. The craft is exquisite, the comedy deeply satiating. What Louise Wallace has achieved in Ash is a monumental call to all the women who have been called good girls and bitches with the same breath. Ash simmers and smokes with honesty. It makes sparks fly.” —Claire Mabey

What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma (translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey) $35

What if one half of a pair of twins no longer wants to live? What if the other can't live without them?This question lies at the heart of Jente Posthuma's deceptively simple What I'd Rather Not Think About. The narrator is a twin whose brother has recently taken his own life. She looks back on their childhood, and tells of their adult lives — how her brother tried to find happiness, but lost himself in various men and the Bhagwan movement, though never completely. In brief, precise vignettes, full of gentle melancholy and surprising humour, Posthuma tells the story of a depressive brother, viewed from the perspective of the sister who both loves and resents her twin, struggles to understand him, and misses him terribly.

”What makes What I’d Rather Not Think About rise above the average mourning novel is its utter authenticity. Posthuma associates, philosophises, links memories to everyday actions, draws on films and television series and tries to interpret in a laconic, light-footed and pointed way. ‘Less is more’ with Jente Posthuma. And again, she seems to be saying: nothing is “whole” here, in the subhuman. Everything rumbles, frays, and creaks.” —Nederlands Letterenfonds

White Nights by Urszula Konek (translated from Polish by Kate Webster) $40

White Nights is a series of thirteen interconnected stories concerning the various tragedies and misfortunes that befall a group of people who all grew up and live(d) in the same village in the Beskid Niski region, in southern Poland. Each story centres itself around a different character and how it is that they manage to cope, survive or merely exist, despite, and often in ignorance of, the poverty, disappointment, tragedy, despair, brutality and general sense of futility that surrounds them.

”The book’s strength lies in its ability to capture the intense, dreamlike quality of its setting, where the natural phenomenon of ‘white nights’ serves as a backdrop for the characters’ introspective journeys. White Nights is a dark, lyrical exploration of the ways in which people seek meaning and belonging in a transient world.” —International Booker Prize judges’ citation

The Russian Detective by Carol Adlam $65

An exquisitely drawn graphic novel, a crime thriller with a strong feminist vein, set in nineteenth century Russia. Journalist and magician Charlie Fox returns to her home town of Nowheregrad to investigate the murder of a glass manufacturer’s daughter, but learns some things about herself, too. Lovingly done, well researched, and full of delights and surprises.

”Could not be more rich or more beautiful if it tried. This is a book that replays multiple readings — its illustrations are so deeply atmospheric and so inordinately beautiful.” —Observer

Mater 2-10 by Hwang Sok-yong (translated from Korean by Sora Kim-Russell and Youngjae Josephine Bae) $40

Centred on three generations of a family of rail workers and a laid-off factory worker staging a high-altitude sit-in, Mater 2-10 vividly depicts the lives of ordinary working Koreans, starting from the Japanese colonial era, continuing through Liberation, and right up to the twenty-first century.

”Mater 2-10 is a vital reminder that, while the Berlin Wall may have fallen, the Cold War lives on in a divided Korea. It traces the roots of postwar persecution of labour activists smeared as ‘commies’. Decades of torture of political opponents in Japanese-built prisons are revealed as a ‘legacy of the Japanese Empire’. Hwang’s aim, he writes, was to plug a gap in Korean fiction, which typically reduces industrial workers to ‘historical specks of dust’. Not only does he breathe life into vivid protagonists, but the novel so inhabits their perspective that we share the shock and disbelief as their hard-won freedom is snatched away.” —Maya Jaggi, The Guardian

Also in stock by Hwang Sok-yong: At Dusk.

Crooked Plow by Itamar Vieira Junior (translated from Portuguese by Johnny Lorenz) $25

“I heard our grandmother asking what we were doing. ‘Say something!’ she demanded, threatening to tear out our tongues. Little did she know that one of us was holding her tongue in her hand.”

Deep in Brazil's neglected Bahia hinterland, two sisters find an ancient knife beneath their grandmother's bed and, momentarily mystified by its power, decide to taste its metal. The shuddering violence that follows marks their lives and binds them together forever. Heralded as a new masterpiece, this fascinating and gripping story about the lives of subsistence farmers in Brazil's poorest region, three generations after the abolition of slavery, is at once fantastic and realist, covering themes of family, spirituality, slavery and its aftermath, and political struggle.

”Bibiana and Belonisía are two sisters whose inheritance arrives in the form of a grandmother’s mysterious knife, which they discover while playing, then unwrap from its rags and taste. The mouth of one sister is cut badly and the tongue of the other is severed, injuries that bind them together like scar tissue, though they bear the traces in different ways. Set in the Bahia region of Brazil, where approximately one third of all enslaved Africans were sent during the height of the slave trade, the novel invites us into the deep-rooted relationships of Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous peoples to their lands and waters – including the ways these communities demand love, gods, song, and dream – despite brutal colonial disruptions. An aching yet tender story of our origins of violence, of how we spend our lives trying to bloom love and care from them, and of the language and silence we need to fuel our tending.” —International Booker Prize judges’ citation

A Different Light: First photographs of Aotearoa edited by Catherine Hammond and Shaun Higgins $65

In 1848, two decades after a French inventor mixed daylight with a cocktail of chemicals to fix the view outside his window onto a metal plate, photography arrived in Aotearoa. How did these 'portraits in a machine' reveal Maori and Pakeha to themselves and to each other? Were the first photographs 'a good likeness' or were they tricksters? What stories do they capture of the changing landscape of Aotearoa? From horses laden with mammoth photographic plates in the 1870s to the arrival of the Kodak in the late 1880s, New Zealand's first photographs reveal Kingi and governors, geysers and slums, battles and parties. They freeze faces in formal studio portraits and stumble into the intimacy of backyards, gardens and homes. A Different Light brings together the extraordinary and extensive photographic collections of three major research libraries — Tamaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum, Alexander Turnbull Library and Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hakena. Beautifully presented, with many of the images never before published.

The Home Child by Liz Berry $45

In 1908, Eliza Showell, twelve years old and newly orphaned, boards a ship that will carry her from the slums of the Black Country to rural Nova Scotia. She will never return to Britain or see her family again. She is a Home Child, one of thousands of British children sent to Canada to work as indentured farm labourers and domestic servants. In Nova Scotia, Eliza's world becomes a place where ordinary things are transfigured into treasures - a red ribbon, the feel of a foal's mane, the sound of her name on someone else's lips. With nothing to call her own, the wild beauty of Cape Breton is the only solace Eliza has — until another Home Child, a boy, comes to the farm and changes everything. Inspired by the true story of Liz Berry's great aunt, this novel in verse is an evocative portrait of a girl far from home.

”A profound act of witness to a long injustice, and a beautifully crafted conjuring of a life lived as truly as possible.” —Guardian

Dear Colin, Dear Ron: The selected letters of Colin McCahon and Ron O’Reilly edited by Peter Simpson $65

The painter Colin McCahon and the librarian Ron O'Reilly first met in 1938, in Dunedin, when McCahon was 19 and O'Reilly 24. They remained close, writing regularly to each other until 1981, when McCahon became too unwell to write. Their 380 letters covered McCahon's art practice, the contemporary art scene, ideas, philosophy and the spiritual life. Dazzling in their range, intensity and candour, the letters track a unique friendship and partnership in art. Simpson's selection represents the first time these letters have been transcribed and collected in what is an act of great generosity to future scholars. It adds a new dimension to an understanding of McCahon and his career and is a rich and lively addition to any art lover's McCahon library. O'Reilly's son Matthew O'Reilly and McCahon's grandson Finn McCahon-Jones contribute insightful essays that round out the unique perspective the letters afford. The book is illustrated with 64 images, all discussed in the letters.

Krabat and the Sorcerer’s Mill by Ottfied Preussler (translated from German by Anthea Bell) $30

New Year's has passed. Twelfth Night is almost here. Krabat, a fourteen-year-old beggar boy dressed up as one of the Three Kings, is traveling from village to village singing carols. One night he has a strange dream in which he is summoned by a faraway voice to go to a mysterious mill — and when he wakes he is irresistibly drawn there. At the mill he finds eleven other boys, all of them, like him, the apprentices of its Master, a powerful sorcerer, as Krabat soon discovers. During the week the boys work ceaselessly grinding grain, but on Friday nights the Master initiates them into the mysteries of the ancient Art of Arts. One day, however, the sound of church bells and of a passing girl singing an Easter hymn penetrates the boys' prison: At last a plan is set in motion that will win them their freedom and put an end to the Master's dark designs.

"One of my favorite books." —Neil Gaiman

worm, root, wort… & bane by Ann Shelton $54

Artist Ann Shelton’s latest book, worm, root, wort… & bane delves into the rich history of plant-centric belief systems and their suppression. Part artist scrapbook, part photo book, part quotography, and part exhibition catalogue, this publication explores the medicinal, magical, and spiritual uses of plant materials, once deeply intertwined with the lives of European forest, nomadic, and ancient peoples. worm, root, wort… & bane re-assembles fragments of historical knowledge alongside the first 19 artworks from Shelton’s photographic series, i am an old phenomenon (2022-ongoing). The plant sculptures photographed are constructed by the artist, who has worked with plants since childhood and long been interested in the history of floral art and its expansive gendered resonances. Overflowing with 300+ images and quotations, this book traces the loss of plant knowledge held wise women, witches, and wortcunners in post-feudal Europe, as Christianity spread and capitalism emerged. The book follows our changing relationships with plants, through the Victorian era to the present — offering cause to reflect on the consequences of the ongoing estrangement between humans and the natural world.

Before he was catapaulted into the literary sphere at the age of 42 with the publication of Heart of Darkness in 1899, Joseph Conrad worked as a merchant seaman and frequented ports in Australia and New Zealand between 1878 and 1893 (he captained the Otago until he declined to repeat a sugar-trade run between Australia and Mauritius). Martin Edmond does a superb job of tracing Conrad’s ghost in the Antipodes, and reveals how many elements, incidents and characters in his fiction draw directly from his experiences in this part of the world. As always, Edmond’s style, precision and personal, thoughtful approach to writing non-fiction make the book a pleasure to read.

A selection of books from our shelves. Solve your book problem with a new mystery.

Click through to find out more:

Read our latest newsletter!

5 April 2024.

Move through autumn with a book in your hand!

The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg (translated from Swedish by Deborah Bragan-Turner)

In this beautifully abject and uncomfortable biographical novel, Sara Stridsberg suspends her subject, Valerie Solanas, indefinitely at the point of death in San Francisco’s disreputable Bristol Hotel in 1988 and subjects her to a long sequence of interrogations by a self-styled ‘narrator’, superimposing upon the distended moment of death two additional narratives stands: of her life from childhood until the moment Solanas shot Andy Warhol in 1968, and from the trial via the mental hospital to society's margins and the Bristol hotel. Stridsberg has strung a multitude of short dialogues in these strands, typically preceded by the narrator setting the scene, so to call it, in the second person, and then scripting conversations between Solanas and the narrator, or with Solanas’s mother, Dorothy, or with her friend/lover Cosmogirl, or with Warhol or ‘the state’ or a psychiatrist or a nurse, or with the opportunistic Maurice Girodias, whose Olympia Press published Solanas’s remarkable SCUM Manifesto , a radical feminist tirade against the patriarchy at once scathingly acute and deliciously ironic. Stridsberg (aided by her translator into English, Deborah Bragan-Turner) conjures Solanas’s voice perfectly, animating the documentary material in a way that is both sensitive and brutal. This is, of course, both against and absolutely in line with Solanas’s wishes, making herself available to “no sentimental young woman or sham author playing at writing a novel about me dying. You don’t have my permission to go through my material.” The Solanas of the dialogues is often largely the deathbed Solanas, suspended in a liminal state between times and on the edge of consciousness, whereas her interlocutors are more affixed to their relevant times, for instance her mother Dorothy forever caught in Solanas’s childhood - in which Valerie was abused by her father and, later, by her mother’s boyfriends - yet hard to get free of, due to “that life-threatening bond between children and mothers.” The scene/dialogue mechanism that comprises most of the novel appears to remove authorial intrusion from the representation of Solanas’s life more effectively than a strictly ‘factual’ biography would have done, while all the time flagging the fictive nature of the project. “I fix my attention on the surface. On the text. All text is fiction. It wasn’t real life; it was an experience. They were just fictional characters, a fictional girl, fictional figurants. It was fictional architecture and a fictional narrator. She asked me to embroider her life. I chose to believe in the one who embroiders.” Stridsberg does a remarkable job at being at once both clinical and passionate, at undermining our facile distinctions between tenderness and abjection, between beauty and transgression, between radical critique and mental illness, between verbal delicacy and the outpouring of “all these sewers disguised as mouths.” Solanas shines out from the abjection of America, unassimilable, a person with no place, no possible life. “It was an illness, a deranged, totally inappropriate grief response. I laughed and flew straight into the light. There was nothing to respond appropriately to.” At the end of the book the three strands of narrative draw together and terminate together: Solanas shoots Warhol at the moment of her own death two decades later, and the personae are released. All except Warhol, who lived in fear of Solanas thereafter: “People say Andy Warhol never really came back from the dead, they say that throughout his life he remained unconscious, one of the living dead.”

Chanelle Moriah was diagnosed with autism at 21 and ADHD (Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder) at 22. They are the author and Illustrator of I Am Autistic and This Is ADHD. These are practical and informative handbooks for neurodivergent folk and by extension their whanau, friends and colleagues. I’ve just finished reading This is ADHD and I found it extremely useful, as well as interesting. It has helped me start to understand what life is like for someone with ADHD. Why simple tasks become so complicated, what neurodivergence can be, how behaviours can be misinterpreted, and how other disorders (depression and anxiety to name two) can impact the ADHDer. Whether you are (or your loved one is) diagnosed or not, this book will be helpful. In the first reading, it has given me more understanding and knowledge about ADHD, and hopefully prepared me to be a better parent and support person. The book is set out with a bold pattern and colour palette, with passages highlighted, and plenty of lists and tick-boxes. The text is in a hand-written style (not a typed font), which surprised me. Moriah has made this book the way that makes sense to them and sits comfortably for someone with ADHD. I was also surprised at the references that jump you forward and back in the book, but after reading about boredom and ADHD this all made sense. There are plenty of spaces and pages to write on, with only a swirl of colour — no completely blank pages. There are many short chapters on numerous aspects (some which will be relevant to the individual, others not — Moriah stresses that ADHD is diverse), including sleep, mood, anxiety, talking too much, zoning out, dopamine, and learning styles. Moriah tells it as it is: they give plenty of options and tools for dealing with some of the challenges of ADHD, but also celebrate the benefits. This is ADHD is empowering, interactive and an excellent resource for anyone interested in neurodiversity.

Move through autumn with a book in your hand!

Click through to place your orders:

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud $40

Noreen Masud has always loved flat landscapes — their stark beauty, their formidable calm, their refusal to cooperate with the human gaze. They reflect her inner world- the 'flat place' she carries inside herself, emotional numbness and memory loss as symptoms of childhood trauma. But as much as the landscape provides solace for this suffering, Britain's flatlands are also uneasy places for a Scottish-Pakistani woman, representing both an inheritance and a dispossession. Pursuing this paradox across the wide open plains that she loves, Noreen weaves her impressions of the natural world with the poetry, folklore and history of the land, and with recollections of her own early life, rendering a startlingly strange, vivid and intimate account of a post-traumatic, post-colonial landscape — a seemingly flat and motionless place which is nevertheless defiantly alive.

”It would be easy to assume that A Flat Place, dealing as it does in the currency of trauma, racism and exile, is a bleak book. But this memoir is too interested in what it means and how feels to be alive in a landscape to be anything other than arresting and memorable. In the flatlands of Britain, and in the memories they evoke of the flat places of Pakistan, Masud both finds a way to comprehend her own story and establishes a strong voice that confirms her as a significant chronicler of personal and national experience. A Flat Place is a slim volume, but that belies its expansive scope.” —Financial Times

Te Waka Hourua Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika! $30

Following the treaty redaction action at Te Papa by Te Waka Hourua in December 2023, this book authored by the artists themselves is a first-hand recollection and reflection of their experience, complemented with some memorabilia of the action, and its impact in the public discourse. Te Waka Hourua is a tangata whenua-led, direct action, climate and social justice rōpū. Their kaupapa is as described by their whakaaturanga: “Our waka hourua has set its course. We feel it is beyond time to shed light on the truth of our current and existential situation; endless destruction by an elite minority at the expense of the majority, and of hospitable life on planet earth.”

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow: Wellington street art by Jamie D. Baird $70

Art or vandalism, protest or social commentary — how you see street art depends on where you stand. Jamie Baird’s Here Today Gone Tomorrow documents his 40-year fascination with these ephemera as “a testament to human imagination, innovation and cultural diversity.” The fascinating book, with over 1200 photographs taken over four decades, really captures the variety and vitality that is Wellington's unofficial culture and true life.

Granta 165: Deutschland edited by Thomas Meeney $35

From Lower Saxony to Marienbad, the carwash to the planetarium, this issue of Granta reflects on Germany today. Featuring non-fiction by Alexander Kluge, Peter Handke, Fredric Jameson, Lauren Oyler, Michael Hofmann, Peter Kuras, Adrian Daub, Peter Richter, Lutz Seiler, Ryan Ruby, Jan Wilm and Jürgen Habermas. As well as a conversation between George Prochnik, Emily Dische-Becker and Eyal Weizman. The issue introduces two young novelists on the German scene – Leif Randt and Shida Bazyar – forthcoming work from Yoko Tawada, a short story from Clemens Meyer, and autofiction by Judith Hermann. Plus, poetry by Elfriede Czurda and Frederick Seidel. Photography by Martin Roemers (with an introduction by the poet Durs Grünbein); Ilyes Griyeb (with an introduction by Imogen West-Knights) and Elena Helfrecht (with an introduction by Hanna Engelmeier).

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar $38

Cyrus Shams is lost. The orphaned son of Iranian immigrants, Cyrus never knew his mother. Killed when her plane was shot down over the Persian Gulf in a senseless accident, Cyrus has spent his life grappling with the meaningless nature of his mother’s death. Now he is set to learn the truth of her life. When Cyrus’s obsession with the lives of the martyrs – Bobby Sands, Joan of Arc – leads him to a chance encounter with a dying artist, he finds himself drawn towards the mysteries of his past: an uncle who rode through Iranian battlefields dressed as the Angel of Death; and toward his mother, who may not have been who or what she seemed. As Cyrus searches for meaning in the scattered clues of his life, a final revelation transforms everything he thought he knew.

”As a poet, Akbar is a master of economy of language, and that mastery remains untouched in this 350-page novel. The writing in Martyr! dances on the page, effortlessly going from funny and witty to deep and philosophical to dialogue that showcases the power of language as well as its inability to discuss certain things. It brilliantly explores addiction, grief, guilt, sexuality, racism, martyrdom, biculturalism, the compulsion to create something that matters, and our endless quest for purpose in a world that can often be cruel and uncaring. Akbar was already known as a great poet, but now he must also be called a great, fearless novelist.” —NPR

Service by Sarah Gilmartin $37

When Hannah learns that famed chef Daniel Costello is facing accusations of sexual assault, she's thrust back to the summer she spent as a waitress at his high-end Dublin restaurant. Drawn in by the plush splendour of the dining rooms, the elegance of the food, the wild parties after service, Hannah also remembers the sizzling tension of the kitchens. And how the attention from Daniel morphed from kindness into something darker... His restaurant shuttered, his lawyers breathing down his neck, Daniel is in a state of disbelief. Decades of hard graft, of fighting to earn recognition for his talent - is it all to fall apart because of something he can barely remember? Hiding behind the bedroom curtains from the paparazzi's lenses, Julie is raking through more than two decades spent acting the supportive wife, the good mother, and asking herself what it's all been for. Their three different voices reveal a story of power and abuse, victimhood and complicity. This is a novel about the facades that we maintain, the lies that we tell and the courage it takes to face the truth.

A Brief Atlas of the Lighthouses at the End of the World by González Macías (translated from Spanish by Daniel Hahn) $50

From a blind lighthouse keeper tending a light in the Arctic Circle, to an intrepid young girl saving ships from wreck at the foot of her father's lighthouse, and the plight of the lighthouse crew cut off from society for forty days, this is a book full of illuminating stories that transport us to the world's most isolated and interesting lighthouses. Over thirty tales, each accompanied by beautiful illustrations, nautical charts, maps, architectural plans and curious facts. Includes the Stephens Island lighthouse in the Marlborough Sounds.

We Need to Talk About Death: An important book about grief, celebrations, and love by Sarah Chavez, illustrated by Annika Le Large $25

A beautifully illustrated, frank and affirming book about death though history and around the world, and also in our own lives. Death is an important part of life, and yet it is one of the hardest things to talk about — for adults as well as children. Reading this book, children will marvel at the flowers different cultures use to represent death. They will find out about eco-friendly burials, learn how to wrap a mummy, and go beneath the streets of Paris to witness skull-lined catacombs! Readers will also ride a buffalo alongside Yama, the Hindu god of death, come face-to-face with the terracotta army a Chinese emperor built to escort him to the afterlife, and party in the streets to celebrate the Day of the Dead in Mexico. Through these examples the book showcases the amazing ways humans have always revered those who have died. Full of practical tips, this book won't stop the pain of losing a loved one or a pet, but it may give young readers ideas for different ways they can celebrate those who have passed away, and help begin the healing process.

The One Straw Revolution by Masanobu Fukuoka (translated from Japanese by Larry Korn) $30

Call it "Zen and the Art of Farming" or a "Little Green Book," Masanobu Fukuoka's manifesto about farming, eating, and the limits of human knowledge presents a radical challenge to the global systems we rely on for our food. At the same time, it is a spiritual memoir of a man whose innovative system of cultivating the earth reflects a deep faith in the wholeness and balance of the natural world. As Wendell Berry writes in his preface, the book "is valuable to us because it is at once practical and philosophical. It is an inspiring, necessary book about agriculture because it is not just about agriculture. "Trained as a scientist, Fukuoka rejected both modern agribusiness and centuries of agricultural practice, deciding instead that the best forms of cultivation mirror nature's own laws. Over the next three decades he perfected his so-called "do-nothing" technique: commonsense, sustainable practices that all but eliminate the use of pesticides, fertilizer, tillage, and perhaps most significantly, wasteful effort. Whether you're a guerrilla gardener or a kitchen gardener, dedicated to slow food or simply looking to live a healthier life, you will find something here.

Erasing Palestine: Free speech and Palestinian freedom by Rebecca Ruth Gould $37

Having been accused of antisemitism for writing an account of the injustices she witnessed in Palestine, Rebecca Ruth Gould embarks on a journey to understand how the fight against antisemitism has been weaponised not to defend civil rights, but to deny them. In this exploration, she comes to a broader understanding of how censorship threatens the intersectional movements against racism and prejudice in all its forms, including antisemitism and anti-Palestinian racism. Gould warns of the consequences if academic freedom is not protected and highlights the importance of free speech for the politics of liberation.

”A detailed, in-depth study that gets to the heart of one of the contemporary world's most contentious issues. A bold and expert expose of the real reasons behind the West's current antisemitism industry: the silencing of Palestinians and their erasure from history.” —Ghada Karmi,

”Never have we been more in need of hearing the heroic voices of Palestinian activists and their supporters, still unwaveringly resisting the ongoing Israeli seizure of their land and daily control over their lives and movement. In this meticulously researched, moving and persuasive book, Rebecca Ruth Gould surveys the ever-mounting silencing of any support for justice for Palestinians with specious accusations of anti-Semitism against any and all of those joining the struggle to end Israel's brutal occupation, including against the author herself. “ —Lynne Segal

Portico: Cooking and Feasting in Rome’s Jewish kitchen by Leah Koenig $62

Over 100 recipes, and photographs of Rome's Jewish community, the oldest in Europe. The city's Jewish residents have endured many hardships, including 300 years of persecution inside the Roman Jewish Ghetto. Out of this strife grew resilience, a deeply knit community, and a uniquely beguiling cuisine. Today, the community thrives on Via del Portico d'Ottavia (the main road in Rome's Ghetto neighborhood) — and beyond. Leah Koenig's recipes showcase the cuisine's elegantly understated vegetables, saucy braised meats and stews, rustic pastas, resplendent olive oil-fried foods, and never-too-sweet desserts. Home cooks can explore classics of the Roman Jewish repertoire with Stracotto di Manzo (a wine-braised beef stew), Pizza Ebraica (fruit-and-nut-studded bar cookies), and, of course, Carciofi alla Giudia, the quintessential Jewish-style fried artichokes. A standout chapter on fritters — showcasing the unique gift Roman Jews have for delicate frying — includes sweet honey-soaked matzo fritters, fried salt cod, and savory potato pastries (burik) introduced by the thousands of Libyan Jews who immigrated to Rome in the 1960s and '70s. Every recipe is tailored to the home cook, while maintaining the flavor and integrity of tradition. Suggested menus for holiday planning round out the usability and flexibility of these dishes. A cookbook for anyone who wants to dive more deeply into Jewish foodways, or gain new insight into Rome

Electric Life by Rachel Delahaye $22

Estrella is the ‘perfect’ society: an immaculate, sanitised, hyper-connected environment where everything is channelled through the digital medium. There is no dirt, no pain, no disease and no natural world. Feelings like boredom are frowned upon and discouraged. Alara is dropped down to London Under and into a new-old world that bewilders and disorientates her. How will she survive in a society where noise, dirt and sometimes pain are everyday experiences, and where food is not synthetic and tastes real? Will she accomplish her mission? Who can she trust? How will she get back to her family and her worry-free life in Estrella? This fast-paced and thrilling story set in a fictional yet believable future explores important themes and asks some big questions about where our society could be heading.

The Spectacular Science of Art: From the Renaissance to the Digital Age by Rob Colson, illustrated by Moreno Chiacchiera $25

What is colour theory? How do artists use maths in their paintings? How do scientists spot forgeries in a laboratory? And many, many more!The bright, busy artworks will encourage science-hungry children to pore over every detail and truly get to grips with the science that underpins everything around us. Clear information is delivered on multiple levels, allowing readers to dip in and out at speed, or take a deep dive into their favourite subjects.

Island of Whispers by Frances Hardinge, illustrated by Emily Gravett $38

On the misty island of Merlank, the lingering dead can cause unspeakable harm if they're not safely carried to the Island of the Broken Tower, where they can move on. Milo's father always told him that he wasn't suited for dealing with the dead and could never become the Ferryman — but one day, he's unexpectedly thrust into the role. And his father is his first passenger . . . Milo's father was killed by the Lord of Merlank, in pursuit of his dead daughter who he's unwilling to give up. It's a race to the island as Milo must face swarms of sinister moths, strange headless birds, and dangerous storms to carry his ghostly passengers across the secret seas.

The public service is hot news this week with cuts announced and more cuts to come. It fact, all year the Wellington folk who make the wheels of government turn have been in the churn of the news cycle. Not far behind are increasingly loud noises from the coalition government about co-governance and the place of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. It seems like a very good time to read Tīhema Baker’s satirical, but highly perceptive, novel Turncoat.

Daniel is a young, idealistic Human, determined to make a difference for his people. He lives in a distant future in which Earth has been colonised by aliens. His mission: infiltrate the Alien government called the Hierarch and push for it to honour the infamous Covenant of Wellington, the founding agreement between the Hierarch and Humans.

With compassion and insight, Turncoat explores the trauma of Māori public servants and the deeply conflicted role they are expected to fill within the machinery of government. From casual racism to co-governance, Treaty settlements to tino rangatiratanga, Turncoat is a timely critique of the Aotearoa zeitgeist, holding a mirror up to Pākehā New Zealanders and asking: “What if it happened to you?”

Find out more:

Listen to Tīhema Baker

Longlisted for the JANN MEDLICOTT ACORN PRIZE FOR FICTION (and in the running for the Best First Book Award!)

Another standout from excellent indie publisher Lawrence & Gibson

We will be discussing Turncoat at our TALKING BOOKS session in May!

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more: