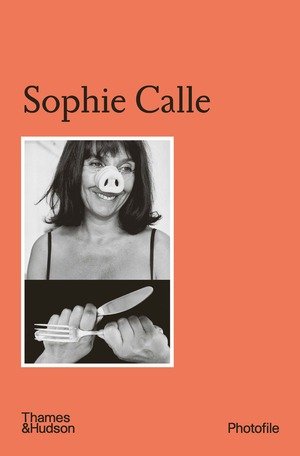

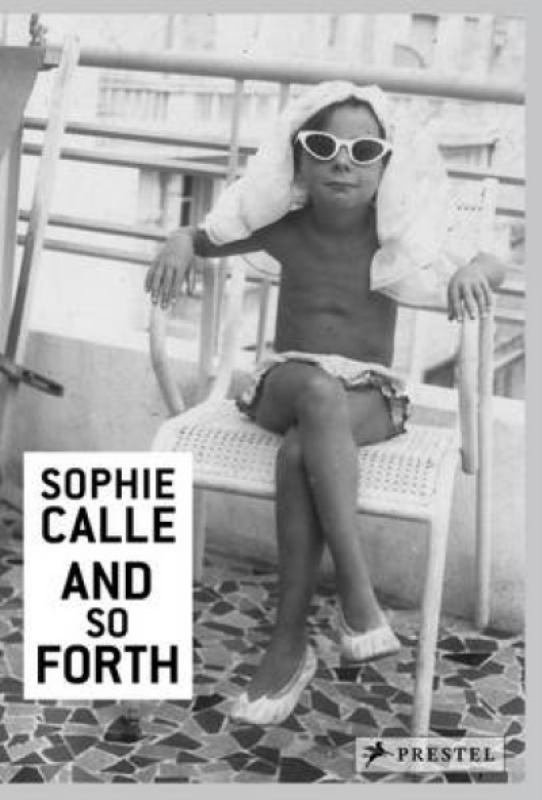

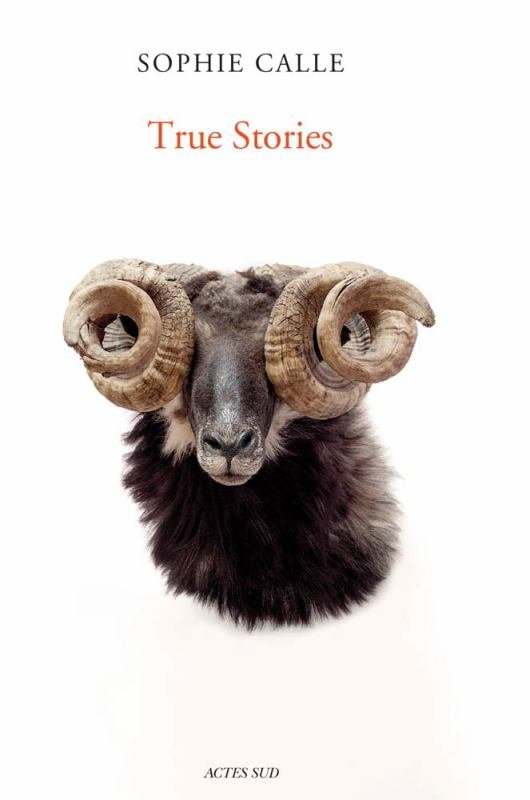

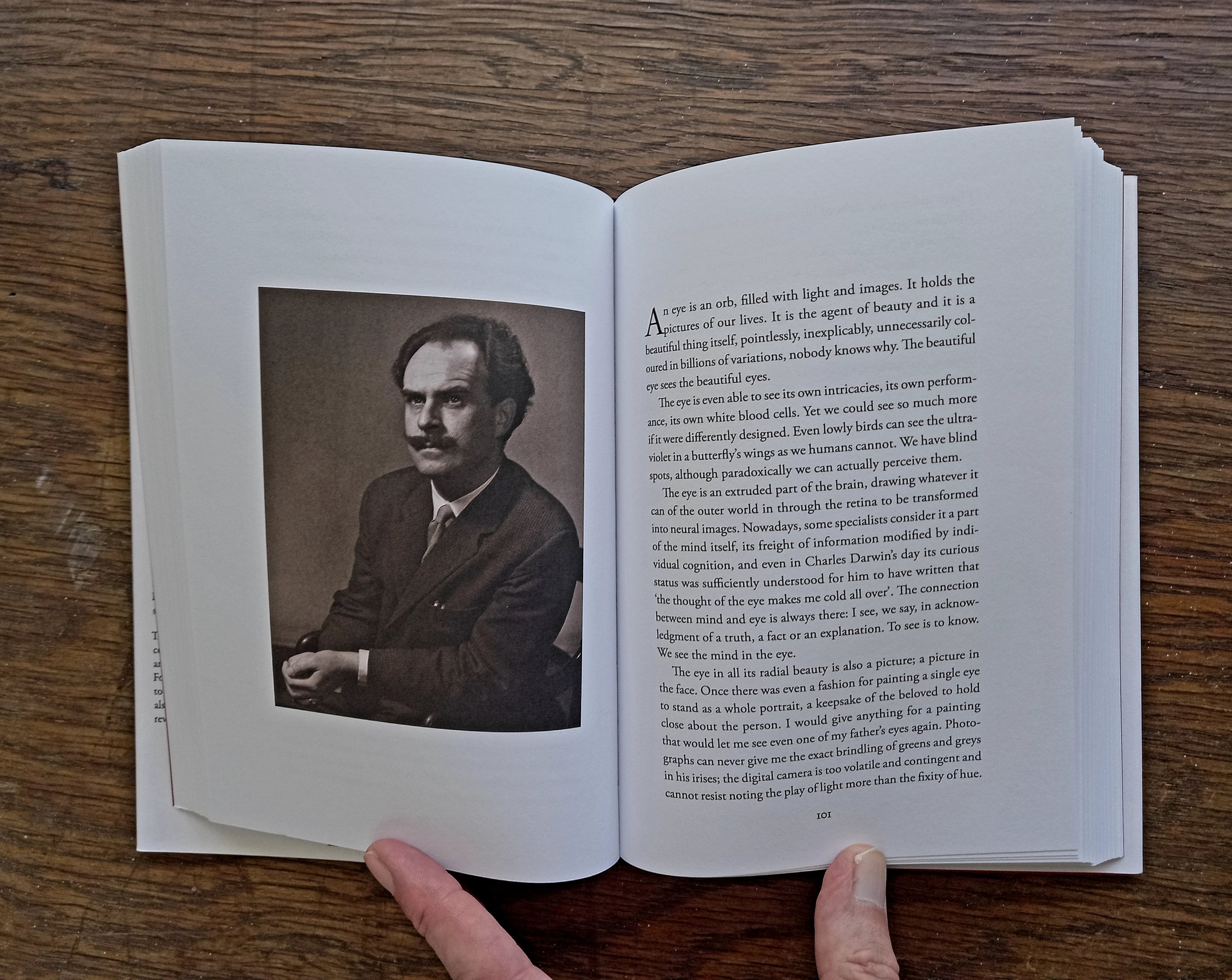

Any idea that we have of ourselves, and it is difficult to avoid forming an an idea of ourselves even though we have nothing but functional reasons to do so, not that functional reasons for this, or for anything else for that matter, are not sufficient, or, in fact, the only possible, reasons, is a fiction, depending on what we understand as a fiction, constructed around, or, more accurately, by, the evidence, so to call it, that presents itself, or is sought, in the phenomenon known generally as memory. How does the past, given that it is convenient for us to consider, for the purposes of this rumination at least, that there is an actual progression through states of what, for want of a better word, we might call, lazily, the universe, or, lazily and sloppily, reality, or vaguely but pedantically, if it is possible to be vague and pedantic simultaneously, actuality, persist into the present in order to provide us with sufficient evidence, the word used cautiously but inverted commas resisted, for these fictions that pass, for us and/or for others, as identities, personalities and other such trappings and conveniences, that enable, or enable the illusion of, or the belief in, our agency as entities at once immersed in and in opposition to the other agglutinations of our existence, so to call them, vaguely, those entities that are not us but which are necessary for us to define ourselves against by the relations of action or perception? It is precisely to avoid such nested clauses and to save excessive wear to the comma keys on our computer keyboards that by convention we eschew the pedantic compulsion, if we can, to apply the rigours of uncertainty to the basic functional fictions such as that of the persistence of entities through time, despite whatever changes to these entities occur. Indeed we seem seldom to be uncertain of the persistence of an entity despite such changes, often more seldom the greater or more transforming these changes, as with the changes expressed by the entities we think of as ourselves, given that we have the idea of ourselves as entities. In any case, given that we deceive ourselves and others merely for the sake of functional convenience, which is only reprehensible in an abstract sense, if indeed reprehensibility can be anything other than abstract, we construct our fictions around the evidence of moments, thought of as in the past, persisting as images, in whatever way we may think of images, the meaning of a word tailored always to the demands of its application, to the present. Photographs, despite whatever other meanings we may impute upon them, seem to demand from us a response such as that expected by a moment of the past persisting to the present, very like, in many ways, the images and fragments from which the fictions, the not untrue fictions, or at least the not necessarily untrue fictions, or what we perhaps may term our functionally true fictions, we think of as our memories. Sophie Calle’s excellent True Stories is a series of images related to what we are encouraged to think of, and have no reason not to think of, as her life, images with, to me at least, and, presumably, also to Calle, and, reasonably, perhaps, to most people, the resonance and texture of the fragments to which we pin, or from which we construct, the memories so described and undercut above. Each is accompanied by a brief memory-text by Calle, which gives the resonance of the image a responding or corresponding context in the story of her life. These texts, funny, sad, tragic, empowering, unsparing of herself and others, or merely straightforward, if such a thing is possible, describe, in the most efficient manner, what we may think of as the character of Calle. The images and the texts have equal weight, and the rigours of the process of recording are sufficiently evident to induce in the reader/viewer of this book the complementary rigours of reception that make the project of awareness concomitant to existence so rewarding.