A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Read our latest newsletter. Read our reviews. Discover new and interesting books. Find out which books have been shortlisted for the 2024 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

8 March 2024 (International Women’s Day)

“Take Two moves beyond the conventions of family memoir, fusing narrative with something like the spirit of a compendium or almanac, gathering up song titles, drawings of household objects, letter extracts, playscripts, poems, and illuminated micro-stories. The book accumulates into a vivid portrait of a family of German and British heritage, set up in post-WW2 London and torn between impulses to close ranks or break apart. It’s a fascinating and provocative act of witnessing, one that offers up new insights and patterns with each re-reading.” —Michael Loveday

Here’s a gem of a book. Take Two is a project by two sisters about growing up in post-war London which subtly reveals more than you expect. It is published by the excellent CB Editions, the small (one-man) publishing house of the well-regarded Charles Boyle, who in his recent newsletter (in which he breaks down the negative profit of publishing books) stated, “If I’m putting a book into the world — adding to the world’s sheer stuff — I want, obviously, this book to be a decent thing”. Caroline and Vivian Thonger, among other things, are both writers: Caroline of non-fiction and translation; Vivian poetry and short fictions. Caroline lives in Switzerland and Vivian in Aotearoa, as does the illustrator Alan Thomas. The book is a collection of short pieces, of episodes, that cleverly coalesce to build a picture of a sometimes fraught family life, through childhood memories, letters, remembered pieces of music, and household objects. There are micro-stories, poems, and short plays, all working together to reveal the dynamics of family life and familial relationships. For Caroline and Vivian, their parents figure strongly, each a dominating presence in their lives. Their mother, Ursula, seems glamorous and unconventional — she’s continental and fiercely independent, which must have made her unusual in the Britain of the 1950s, while her mother (the German grandmother), the rather daunting Oma, is opinionated and yet wry. When her sister suddenly dies landing face down in her pudding, she announces that it is very inconvenient. Their father, Richard, is a complex individual. Cambridge-educated, but it's difficult to place him in Britain’s society of the time — he seems contradictory to his core. Immersed in his study surrounded by words within a cloud of smoke, he’s obviously an intellectual, but he’s prone to fly off the handle and his temper has little regard for his daughters’ feelings, particularly Caroline, his eldest child. This is what I gather from reading the entries in this volume, and reading between the lines, for it is not spelled out. Both sisters have set aside their adult knowledge to rekindle the child’s viewpoint. It is deliberate and makes this memoir so very captivating. For the reader these impressions, along with our adult perspective and experiences, allow us to join the dots and fit the pieces into the jigsaw puzzle. Whether we do this accurately is beside the point, for memory is not accurate and perspectives are usually varied. There are ordinary childhood accounts followed by traumatic events, evenly told so that the reader does not notice at first and then pauses in shock. Look for the clues in the addresses in London as the family moves and dynamics change between the parents. See the summer holiday entries, hiking in France with their too-ambitious father or the visits to relatives which are laced with snippets of information. Follow as the sisters recount their childhood — their voices melding — and then take their own paths as young adults. Add in the delightful drawings of Alan Thomas of remembered household objects, which tell their own story of a place and a time. The illustrations have revealing snippets of text. “Item 15: Coat hanger, padded, floral pattern, used to discipline teenage girls.” These fleeting glimpses offer us so much. In the final few pieces, some disquieting revelations come to light, demanding that you read again, much as one revisits one’s life with new-found knowledge. These facts have been sitting there the whole time, subtly in the sub-conscious of Take Two. This two-sister project is innovative, enjoyable, and a wonderfully distinct gem.

Humans have continued to evolve, he thought, by making objects that are extensions of themselves, extensions not only in a physical and practical sense but in a mental sense also. Thinking is done mainly outside my head, he thought, my memories and intentions are embodied in and enacted by the great commonwealth of objects in which I hang suspended, displacing my volume perhaps, but entirely at the mercy of objects that mediate my every experience and over which I have only very narrow and limited control. These objects grasp me more tightly than ever I could grasp them, he thought, they define the scope of my thoughts and actions, they call to each other through the qualities they share with each other, and they bind me to all the other people similarly caught in this inescapable infinite web of objects. I am caught, he thought, I am connected through objects to everyone and to everything that everyone does with any object anywhere. I am not sure that I like this. Through the objects around me, both useful and ornamental, through these objects’ connections with and similarities to other and yet other objects, I am implicated in all actions committed by all humans using objects that embody intentions, that are made for a purpose or suggest themselves as suitable for a purpose, that are available for the use of humans, that press their purpose on the minds of humans. We are all connected through objects because all objects are connected. “Everything in this damned world calls for indignation,” states the protagonist, so to call her, of Lara Pawson’s excellent little book, Spent Light. Although the ostensible scope of the book is entirely domestic and simple and small and plausibly claustrophobic, the quotidian household objects that she considers, objects that are seldom considered but merely used, reveal, by similarity, connections with objects used in and enabling acts of violence, injustice and exploitation committed on both humans and the environment anywhere in the world. A pepper mill is connected to a grenade, an egg timer is the same mechanism used to detonate a time bomb, on the toaster given to her by her disconcerting neighbour “above each light is a word printed in the same restrained font found in CIA documents. Together, they form a synopsis of the anthropocene: REHEAT DEFROST CANCEL”. Every characteristic of every thing twitches a web of association and resemblance often leading to her memories or at least knowledge of despicable actions committed with similar objects or implicated by the functions of her objects somewhere distant or else. These associations often reveal Pawson’s close observation of cruelties from her time as a war reporter in parts of the world seemingly different from but in fact not unconnected with her current rather domestic existence. But although the reader never knows when they will next be shocked by Pawson’s association of an object, an object that they very likely have themselves or which is very similar to an object that they have in their own intimate environment, with an act of cruelty, torture or genocide, an association that may change forever the way that the reader looks at their own object, the same world-wide web of objects that links us to these acts contains also associations that connect us, despite or because of the objects that we own, with others in acts of support, nurture or love; acts of support, nurture and love that are all the more angry, vital and beautiful because of the global contexts in which they must be waged. Lara Pawson, he thought, on the evidence of this book, is good company in the waging of such acts.

Choose your next book straight out of the cartons that arrived this week:

La Bâtarde by Violette Leduc (translated from French by Derek Coltman) $35

An obsessive and revealing self-portrait of a remarkable woman humiliated by the circumstances of her birth and by her physical appearance, La Bâtarde relates Violette Leduc's long search for her own identity through a series of agonizing and passionate love affairs with both men and women. When first published, La Bâtarde earned Violette Leduc comparisons to Jean Genet for the frank depiction of her sexual escapades and immoral behavior. A confession that contains portraits of several famous French authors, this book is more than just a scintillating memoir--like that of Henry Miller, Leduc's brilliant writing style and attention to language transform this autobiography into a work of art.

”Notoriety aside, Leduc is first and foremost a first-rate writer. Not someone who just tells a provocative story and is unafraid to reveal the most offensive parts of her personality and of her experience, but someone who is in love with words, struggles with them, wrestles with language, dies for adjectives, is tortured by her search for le mot juste." —Women's Review of Books

North Woods by Daniel Mason $38

When a pair of young lovers abscond from a Puritan colony, little do they know that their humble cabin in the woods will become the home of an extraordinary succession of human and inhuman characters alike. An English soldier, destined for glory, abandons the battlefields of the New World to devote himself to apples. A pair of spinster twins navigate war and famine, envy and desire. A crime reporter unearths a mass grave - only to discover that the ancient trees refuse to give up their secrets. A lovelorn painter, a sinister conman, a stalking panther, a lusty beetle: as each inhabitant confronts the wonder and mystery around them, they begin to realize that the dark, raucous, beautiful past is very much alive.

”A monumental achievement . . . it sweeps the reader through hundreds of years and an array of protagonists with a deft, heartbreaking, idiosyncratic zeal. I loved it.” —Maggie O'Farrell

I Seek a Kind Person: My father, seven children, and the adverts that helped them escape the Holocaust by Julian Borger $38

'I SEEK A KIND PERSON WHO WILL EDUCATE MY INTELLIGENT BOY, AGED 11.' In 1938, Jewish families are scrambling to flee Vienna. Desperate, they take out advertisements offering their children into the safe keeping of readers of a British newspaper, the Manchester Guardian. The right words in the right order could mean the difference between life and death. Eighty-three years later, Guardian journalist Julian Borger comes across the advert that saved his father, Robert, from the Nazis. Robert had kept this a secret, like almost everything else about his traumatic Viennese childhood, until he took his own life. Drawn to the shadows of his family's past and starting with nothing but a page of newspaper adverts, Borger traces the remarkable stories of his father, the other advertised children and their families, each thrown into the maelstrom of a world at war. From a Viennese radio shop to the Shanghai ghetto, internment camps and family homes across Britain, the deep forests and concentration camps of Nazi Germany, smugglers saving Jewish lives in Holland, an improbable French Resistance cell, and a redemptive story of survival in New York, Borger unearths the astonishing journeys of the children at the hands of fate, their stories of trauma and the kindness of strangers.

”A powerful, eloquent and deeply affecting book. I loved it.” —Edmund de Waal

”Julian's book is profoundly affecting, part memoir, part detective story, part history, at once elegiac and fascinating, it is so deeply relevant for our times, I zipped through it with the deepest personal interest.” —Philippe Sands,

Your Utopia by Bora Chung (translated from Korean by Anton Hur) $35

From the author of Cursed Bunny, Your Utopia is full of tales of loss and discovery, idealism and dystopia, death and immortality. "Nothing concentrates the mind like Chung's terrors, which will shrivel you to a bouillon cube of your most primal instincts" (Vulture), yet these stories are suffused with Chung's inimitable wry humour and surprisingly tender moments, too — often between unexpected subjects. In 'The Center for Immortality Research', a low-level employee runs herself ragged planning a fancy gala for donors, only to be blamed for a crime she witnessed during the event, under the noses of the mysterious celebrity benefactors hoping to live forever. But she can't be fired - no one can. In 'One More Kiss, Dear', a tender, one-sided love blooms in the A.I.-elevator of an apartment complex; as in, the elevator develops a profound affection for one of the residents. In 'Seeds', we see the final frontier of capitalism's destruction of the planet and the GMO companies who rule the agricultural industry in this bleak future, but nature has ways of creeping back to life.

”Chung's writing is haunting, funny, gross, terrifying - and yet when we reach the end, we just want more.” —Alexander Chee

Fevered Planet: How diseases emerge when we harm nature by John Vidal $39

Covid-19, mpox, bird flu, SARS, HIV, AIDS, Ebola; we are living in the Age of Pandemics — one that we have created. As the climate crisis reaches a fever pitch and ecological destruction continues unabated, we are just beginning to reckon with the effects of environmental collapse on our global health. Fevered Planet exposes how the way we farm, what we eat, the places we travel to, and the scientific experiments we conduct create the perfect conditions for deadly new diseases to emerge and spread faster and further than ever. Drawing on the latest scientific research and decades of reporting from more than 100 countries, former Guardian environment editor John Vidal takes us into deep, disappearing forests in Gabon and the Congo, valleys scorched by wildfire near Lake Tahoe and our densest, polluted cities to show how closely human, animal and plant diseases are now intertwined with planetary destruction. He calls for an urgent transformation in our relationship with the natural world, and expertly outlines how to make that change possible.

”Urgent, fascinating and essential.” —George Monbiot

”John Vidal has travelled far and wide, and we would be wise to take seriously the reports he sends back; human lives, particularly of the rich, are not just altering the planet in devastatingly predictable ways, they are setting us up for some nasty surprises.” —Bill McKibben

”A searing, vital work. Plagues and epidemics determine human history - now it is time to learn that how we live today is driving disease on a planetary level.” —Bettany Hughes

”Drawing on a lifetime's experience as a frontline journalist, John Vidal compellingly joins the dots between accelerating climate change, population growth, dangerously disrupted ecosystems, our obsession with economic growth - and the inevitability of future pandemics. Fevered Planet is the most illuminating and disturbing book I've read in years.” —Jonathon Porritt

Sounds Good! Discover 50 instruments by Ole Könnecke and Hans Könnecke $40

What does a double bass or a sitar sound like? What's the difference between bongos and congas? Which instrument has only one note? Which one takes just 30 seconds to learn? What do these instruments really sound like? This book engagingly presents 50 common and uncommon musical instruments with practical and curious facts that will spark interest in music of all kinds. Each instrument features a piece of music composed by an award-winning musician, accessed via QR code. Very appealingly presented and full of good information.

Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil by Timothy Mitchell $32

Oil is a curse, it is often said, that condemns the countries producing it to an existence defined by war, corruption and enormous inequality. Carbon Democracy tells a more complex story, arguing that no nation escapes the political consequences of our collective dependence on oil. It shapes the body politic both in regions such as the Middle East, which rely upon revenues from oil production, and in the places that have the greatest demand for energy. Timothy Mitchell begins with the history of coal power to tell a radical new story about the rise of democracy. Coal was a source of energy so open to disruption that oligarchies in the West became vulnerable for the first time to mass demands for democracy. In the mid-twentieth century, however, the development of cheap and abundant energy from oil, most notably from the Middle East, offered a means to reduce this vulnerability to democratic pressures. The abundance of oil made it possible for the first time in history to reorganize political life around the management of something now called "the economy" and the promise of its infinite growth. The politics of the West became dependent on an undemocratic Middle East. In the twenty-first century, the oil-based forms of modern democratic politics have become unsustainable. Foreign intervention and military rule are faltering in the Middle East, while governments everywhere appear incapable of addressing the crises that threaten to end the age of carbon democracy--the disappearance of cheap energy and the carbon-fuelled collapse of the ecological order. In making the production of energy the central force shaping the democratic age, Carbon Democracy rethinks the history of energy, the politics of nature, the theory of democracy, and the place of the Middle East in our common world.

A Line in the World: A year on the North Sea coast by Dorthe Nors (translated from Danish by Caroline Waight) $28

Me, my notebook and my love of the wild and desolate. I wanted to do the opposite of what was expected of me. It's a recurring pattern in my life. An instinct.. There is a line that stretches from the northernmost tip of Denmark to where the Wadden Sea meets Holland in the south-west. Dorthe Nors, one of Denmark's most acclaimed contemporary writers, grew up on this line; a native Jutlander, her childhood was spent among the storm-battered trees and wind-blasted beaches of the North Sea coast. In A Line in the World, her first book of non-fiction, she recounts a lifetime spent in thrall to this coastline - both as a child, and as an adult returning to live in this mysterious, shifting landscape. This is the story of the violent collisions between the people who settled in these wild landscapes and the vagaries of the natural world. It is a story of storm surges and shipwrecks, sand dunes that engulf houses and power stations leaching chemicals into the water, of sun-creased mothers and children playing on shingle beaches. In this singularly thrilling work, Nors invites the reader on a journey through history and memory - the landscape's as well as her own.

”'A beautiful, melancholy account of finding home on a restless coast. In Dorthe Nors's deft hands, the sea is no longer a negative space, but a character in its own right. I loved it.'“ —Katherine May

Every Man for Himself and God against All: A memoir by Werner Herzog $55

From his early movies to his later documentaries, he has made a career out of exploring the boundaries of human endurance: what we are capable of in exceptional circumstances and what these situations reveal about who we really are. But these are not just great cinematic themes. During the making of his films, Herzog pushed himself and others to the limits, often putting himself in life-threatening situations. Filled with memorable stories and poignant observations, Every Man for Himself and God against All unveils the influences and ideas that drive his creativity and have shaped his unique view of the world.

The Taming of the Cat by Helen Cooper $33

A story within a story, featuring a mouse who is forced to tell stories to save his life, a cat who plans to eat said mouse as soon as the story is finished — and our protagonist’s protagonist, a princess in trouble. It’s a lifesaving tale – about a runaway princess, a cat that can grow to the size of a panther, an enchanted feast, a vanishing cavern and a quest to find a magical herb. But the cat is getting hungry. If the mouse wants its life to be spared, this must be the best story he has ever told.

My Baby Sister is a Diplodocus by Aurore Petit $30

is a delightful and excellent introduction to being a sibling. Perfect for anyone embarking on this adventure: the excitement, the pitfalls, the frustration, and the curiosity. From the wonderful French author and illustrator Aurore Petit (her previous book was the thoughtful A Mother is A House), translated by Daniel Hahn and published by Gecko Press.

Alebrijes: Flight to a New Haven by Donna Barba Higuera $20

For 400 years, Earth has been a barren wasteland. The few humans that survive scrape together an existence in the cruel city of Pocatel - or go it alone in the wilderness beyond, filled with wandering spirits and wyrms. They don't last long. 13-year-old pickpocket Leandro and his sister Gabi do what they can to forge a life in Pocatel. The city does not take kindly to Cascabel like them - the descendants of those who worked the San Joaquin Valley for generations. When Gabi is caught stealing precious fruit from the Pocatelan elite, Leandro takes the fall. But his exile proves more than he ever could have imagined - far from a simple banishment, his consciousness is placed inside an ancient drone and left to fend on its own. But beyond the walls of Pocatel lie other alebrijes like Leandro who seek for a better world - as well as mutant monsters, wasteland pirates, a hidden oasis, and the truth.

How I Won a Nobel Prize by Julius Taranto $38

Helen, a graduate student on a quest to save the planet, is one of the best minds of her generation. But when her irreplaceable advisor’s student sex scandal is exposed, she must choose whether to give up on her work or accompany him to RIP, a research institute which grants safe harbour to the disgraced and the deplorable. As Helen settles into life at the institute alongside her partner Hew, she develops a crush on an older novelist, while he is drawn to an increasingly violent protest movement. As the rift between them deepens, they both face major – and potentially world-altering – choices. How I Won A Nobel Prize approaches contemporary moral confusion in a fresh way, examining the price we’re willing to pay for progress and what it means, in the end, to be a good person.

16 excellent books have been short-listed for this year’s OCKHAM NEW ZEALAND BOOK AWARDS.

Find out what the judges have to say, and click through to secure your copies:

JANN MEDLICOTT ACORN PRIZE FOR FICTION

A Better Place by Stephen Daisley (Text Publishing) $38

The tragedies of war and prevailing social attitudes are viewed with an unflinching but contemporary eye as Stephen Daisley’s lean, agile prose depicts faceted perspectives on masculinity, fraternity, violence, art, nationhood and queer love in this story about twin brothers fighting in WW2. With its brisk and uncompromising accounts of military action, and deep sensitivity to the plights of its characters, A Better Place is by turns savage and tender, absurd and wry.

Audition by Pip Adam (Te Herenga Waka Univeristy Press) $35

Three giants hurtle through the cosmos in a spacecraft called Audition powered by the sound of their speech. If they are silent, their bodies continue to grow. Often confronting and claustrophobic, but always compelling, Audition asks what happens when systems of power decide someone takes up too much space and what role stories play in mediating truth. A mind-melting, brutalist novel, skillfully told in a collage of science fiction, social realism, and romantic comedy.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton (Te Herenga Waka University Press) $38

When Mira Bunting, the force behind guerilla gardening collective Birnam Wood, meets her match in American tech billionaire Robert Lemoine, the stage is set for a tightly plotted and richly imagined psychological thriller. Eleanor Catton’s page-turner gleams with intelligence, hitting the sweet spot between smart and accessible. And like an adrenalised blockbuster grafted on to Shakespearian rootstock, it accelerates towards an epic conclusion that leaves readers’ heads spinning.

Lioness by Emily Perkins (Bloomsbury) $25

After marrying the older, wealthier Trevor, Teresa Holder has transformed herself into upper-class Therese Thorn, complete with her own homeware business. But when rumours of corruption gather around one of Trevor’s property developments, the fallout is swift, and Therese begins to reevaluate her privileged world. Emily Perkins weaves multiple plotlines and characters with impressive dexterity. Punchy, sophisticated and frequently funny, Lioness is an incisive exploration of wealth, power, class, female rage, and the search for authenticity.

MARY AND PETER BIGGS AWARD FOR POETRY

At the Point of Seeing by Megan Kitching (Otago University Press) $25

With a polymath’s ear and a photographer’s eye, Megan Kitching creates sharp, complex pictures of the landscapes and lifescapes of Aotearoa. Many of her best poems focus on unruly coastal zones as points of contact, where history is always being made and remade, but she doesn’t ignore the human domain with its ‘petty hungers or awkward flutters’. Importantly, her work insists on the fact that difficult social and political questions cannot be separated from aesthetic ones.

Chinese Fish by Grace Yee (Giramondo Publishing) $30

Grace Yee’s sequence narrates a family’s assimilation into New Zealand life from the 1960s to the 1980s with a striking aesthetic. We navigate swerves in personae, extratextuality, illustrations, Cantonese-Taishanese phrases and English translations provided on the back pages. Yee skillfully bends genres and displaces the reader, evoking the unsettledness of migration. An invigorating read with its tapestry of scenes, characters, food, and language, Chinese Fish contributes a new archival poetics to the Chinese trans-Tasman diaspora.

Root Leaf Flower Fruit by Bill Nelson (Te Herenga Waka University Press) $30

This intriguing verse novel leads us at a walking pace – sometimes tumbling and scraping – across country and suburb, and volatile seasons. There are pivots in perspective and a rich sense of deep time as we encounter nature, injury and recovery, and a settler farming legacy. Bill Nelson’s writing has a sonic quality, protean line breaks, and surprise story threads. The final section with its hint of the New Zealand gothic, is gripping.

Talia by Isla Huia (Te Āti Haunui a-Pāpārangi, Uenuku) (Dead Bird Books)

These poems buzz with energy: intellectual, linguistic, literary. Sharply conceived, engaged in conversation and debate across poetry, place, history, and language, Isla Huia’s work brings unexpected material into productive collision. English and te reo Māori meet this way, as do lines and echoes from older poets with present concerns. Huia has an inspired ear and engaged eye, and her poems’ sonic range and sense of adventure combine with a crafter’s care on the page.

BOOKSELLERS AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND AWARD FOR ILLUSTRATED NON-FICTION

Don Binney: Flight Path by Gregory O’Brien (Auckland University Press) $90

In this wonderfully rich and honest portrait of the artist Don Binney, Gregory O’Brien is never an unquestioning cheerleader for his subject. So while readers see and appreciate his famous works and learn about his interest in both geology and royalty, they also discover his sometimes prickly and sardonic personality. Binney neither liked nor identified with the description ‘bird man’, but hear the name Don Binney and his soaring solo birds come instantly to mind.

Fungi of Aotearoa: A Curious Forager’s Field Guide by Liv Sisson (Penguin Random House) $45

Liv Sisson’s fungi field guide is a joyous combination of information and advice that is totally practical, potentially lifesaving and deliciously quirky. If you don’t know a black landscaping morel from a death cap or a stinky squid from a dog vomit, look no further. Fungi might not move but they are notoriously hard to photograph, so full credit to Paula Vigus and the other photographers for making the mostly tiny subject matter look enticing, and even monumental.

Marilynn Webb: Folded in the Hills by Lauren Gutsell, Lucy Hammonds and Bridget Reweti (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi) (Dunedin Public Art Gallery) $70

From its irresistibly tactile cover to the end note from the Webb estate that the humble Marilynn would have been honoured by the book, this is a magnificent publication. Creating a book from an exhibition has many fishhooks, but the writers, contributors and designer have produced a book that shines. Webb’s life story and her artistic practice are told in both te reo Māori and English, and her art is lovingly and accurately reproduced on the page.

Rugby League in New Zeaqland: A People’s History by Ryan Bodman (Bridget Williams Books) $60

One of Ryan Bodman’s many achievements with this, his first book, is the fact that you don’t have to know or even be interested in rugby league to enjoy it. He presents us with a genuinely fascinating social history which includes identity, women in sport, gangs, politics and community pride in their teams. The photographs taken on and off the field are an absolute treasure-trove of a record of the sport.

GENERAL NON-FICTION AWARD

An Indigenous Ocean: Pacific Essays by Damon Salesa (Bridget Williams Books) $50

Damon Salesa’s collection of essays re-frames our understanding of Aotearoa New Zealand’s colonial history in the South Pacific. A seminal work, An Indigenous Ocean asserts Pacific agency and therefore its ongoing impact worldwide, despite marginalisation by New Zealand and others. Salesa brings together academic rigour, captivating stories and engaging prose, resulting in a masterful book that will endure for generations.

Laughing in the Dark: A Memoir by Barbara Else (Penguin Random House) $40

In this beautifully crafted memoir, Barbara Else reflects on her writing career and its impact on her life. Else’s narrative is both resolute and nuanced, artful and authentic. A story that perhaps could only be told decades after the death of her first husband, Jim Neale – the archetypal patriarchal man in the 1960s and 1970s – Else also explores how toxic masculinity took its toll on him while examining when she herself needed to be held to account.

Ngātokimatawhaorua: Biography of a Waka by Jeff Evans (Massey University Press) $50

Beginning with an expedition into the Puketi forest alongside master waka builder Rānui Maupakanga, Jeff Evans takes us on a vivid journey of discovery as he tells tell the story of the majestic waka taua Ngātokimatawhaorua, a vessel that is both a source of pride and a symbol of wayfaring prowess. Evans’ biography showcases both the whakapapa of the waka, including the influence of Te Puea Hērangi, and its role in the renaissance of voyaging and whakairo (carving) traditions.

There’s a Cure for This: A Memoir by Emma Wehipeihana (Ngāti Tukorehe, Ngāti Porou) (Penguin Random House) $35

Engaging, eloquent and occasionally confronting, Emma Wehipeihana’s [Emma Espiner’s] memoir is comprised of a series of powerful essays about her journey as a Māori woman through both her early life and her time in medical school. Emerging as a doctor, she recounts the racism she and others experience and highlights the structural inequalities in New Zealand’s health system. This book brims with candour, pathos, and wry humour.

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Read our latest newsletter and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending.

1 March 2024

Blue Self-Portrait by Noémi Lefebvre (translated from French by Sophie Lewis)

He had been reading, re-reading in fact, a book that he particularly liked, Noémi Lefebvre’s Blue self-Portrait, from Les Fugitives, a publisher that he also particularly liked, largely because they published books that he particularly liked, such as this one. He had chosen to re-read Blue Self-Portrait, which he remembered as being wonderfully well-written and translated, funny and painful and claustrophobic, all the qualities he wanted in a book, and, he thought, it would be a pity to read at any time anything other than what I most would like to read at that time, even if I have already read it and written a review of it also. In the case of this book that reading and that writing was a while ago, he thought, perhaps not a long while but a while long enough for me to re-use my review without anyone noticing that I have re-used my review, not that anyone reads my reviews anyway, he thought, if they don’t read them they won’t notice that I have re-used my review. It made little sense, he thought, to think that he should fill such reading time as he has with good literature as opposed to less-good literature, it is hard to see what difference this would make, but to do the opposite would make even less sense, and it is impossible not to consider what to read without reference to the real limitation of his time to read, it cannot be unlimited and the world is so full of surprises that could make it more limited still, he thought, somewhat ominously but entirely unspecifically. As my reading time is limited and as it is impossible to know how limited this reading time might be, he thought, I have chosen to read, or re-read, Blue Self-Portrait, and I am doing this without committing myself to writing another review. Let me write or not write, he thought, but, if I write, why write or re-write or overwrite what I have already written? There are only so many words in the world, after all, he thought. Had he read that somewhere? It cannot be the case that there are an infinite number of words he will write, but the opposite doesn’t seem quite right, either. One good sentence would do. Lefebvre could write sentences that he wished that he had written himself, which, for someone who prized a good sentence above all other prizes, earned her his devotion as a reader and perhaps as a writer as well. If a sentence was well enough written, he thought, he could read about anything, but he had less and less time for sentences that were less than excellent, if excellent was the right word, no matter what other qualities they might have, if there are other qualities worth having or qualities to have. All is vacuity, he declared, all is vacuity but the way that vacuity is structured gives meaning. Meaning exists only in grammar if meaning exists at all, he thought, now there’s an aphorism for a calendar. Beyond the sentences there was a musical patterning to the book Blue Self-Portrait, he thought, he recognised a musical grammar of repetitions and variations and motifs probably related to the serialism of Arnold Schoenberg, not something he knew enough about to enlarge upon though probably the case since Schoenberg, both the music of Schoenberg and the painting of Schoenberg, is mentioned often in the book, Schoenberg being the painter of the ‘Blue Self-Portrait’ of the title and the book recognisably musically structured, as opposed to employing the range of mundane structural conventions usually forced upon a novel. In any case, he thought, I shall re-use my review for the book I have re-read, there is nothing wrong with that, because the afternoon has worn on, it is growing cool, there is dinner to be made, there are mosquitoes about, I am boring myself. The world will not be worse off for not having a new review from me this week, the world will be better off. Better off without my blather. When all I can write is an aphorism for a calendar it is better not to write, he thought. If anyone wants a review of what I have been reading they can read my old review, the book hasn’t changed. I have changed and my reading has changed, he supposed, but no-one should care about that, if they want a review let them read my old review, but it would be much better if they just read the book, they don’t need me for that.

Ella loves horses. She loves her gran Grizzly and her home in a southern rural town. She’s most at home on her pony Magpie and cantering across the hills, especially at her favourite time of the day — the grimmelings — a time when magic can happen. Yet she’s lonely and wishes for a friend for the summer. Mum’s busy, and grumpy, looking after everyone and running the trekking business; Grizzly’s getting sicker, although she still has time to tell Ella and her little sister Fiona strange tales and wild stories of Scotland; and the locals think they are a bunch of witches. Ella knows there is power in words and when she curses the bully, Josh Underhill, little does she know she will be in a search party the next day. With Josh missing, and a strangely mesmerising black stallion appearing out of nowhere, this is not your average summer. When Ella meets a stranger, she strikes up an unexpected friendship. Has her wish come true? Why does she feel both attracted and wary of this overly confident boy, Gus? With Josh still missing, Mum’s made the lake out of bounds. That’s the last place Dad was seen six years ago. The lake with its strangely calm centre is enticing. What lurks in its depths — danger or the truth? Rachael King’s The Grimmelings is a gripping story of a girl growing up, of secrets unfolded, and a vengeful kelpie. Like her equally excellent previous children’s book, Red Rocks, King cleverly entwines the concerns of a young teen with an adventure story steeped in mythology. In Red Rocks, a selkie plays a central role, here it is the kelpie. King convincingly transports these myths to Aotearoa, in this case, the southern mountains, and in the former novel, the coast of Island Bay. There are nods to the power of language in the idea of curses, but more intriguing, and touching, are the scraps of paper from Grizzly with new words and meanings for Ella — and for us, the readers. Words are powerful and help us navigate our place in the world and ward off dangers when necessary. Yet the beauty of The Grimmelings lies in its adventure and in the courage of a girl and her horse, who together may withstand a powerful being, and maybe even break a curse. Laced with magical words, intriguing mythology, and plenty of horses, it’s a compelling, as well as emotional, ride.

Out of the carton and into your hands! Choose from some of the new books that arrived this week:

Chinese Fish by Grace Yee $30

When Ping leaves Hong Kong to live in the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand, she discovers that life in the Land of the Long White Cloud is not the prosperous paradise she was led to believe it would be. Every day she works in a rat-infested shop frying fish, and every evening she waits for her wayward husband, armed with a vacuum cleaner to ‘suck all the bad thing out’. Her four children are a brood of monolingual aliens. Eldest daughter Cherry struggles with her mother’s unhappiness and the responsibility of caring for her younger siblings, especially the rage-prone, meat-cleaver-wielding Baby Joseph. Chinese Fish is a family saga that spans the 1960s through to the 1980s. Narrated in multiple voices and laced with archival fragments and scholarly interjections, it offers an intimate glimpse into the lives of women and girls in a community that has historically been characterised as both a ‘yellow peril’ menace and an exotic ‘model minority’. Listed for the 2024 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

”An unflinchingly honest look at life behind closed doors, where resentment simmers, generations clash, and individual dreams are set aside for the interests of family.” —Chris Tse, New Zealand Poet Laureate

”As visually provocative as it is poetic, Chinese Fish portrays the fractured, multilayered, imperiled body of the immigrant story in a stunning work of genre-bending prose poetry. Yee has given the Chin family a literary resting place as complex and as searing as the New Zealand in which they survived.” —Juli Min

”A major poetic work of feminist, so-called ‘minority’ writing, its originality and brilliance more than earning its space alongside such works as Kathleen Fallon’s Working Hot, Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands, and Alison Whittakers’s BlakWork.” – Marion May Campbell

Woven: First Nations poetic conversations edited by Anne-Marie Te Whiu $33

to open up / to respond as genuinely as possible / to offer hope / we want things to change / weaving solidarity from place and history / into collective purpose (Ellen Van Neerven and Layli Long Soldier)

The Fair Trade Project inspired a series of poetic conversations between First Nations poets throughout the world, including Aotearoa, and was commissioned by Red Room Poetry. This collection weaves words across lands and seas, gathering collaborative threads and shining a light on common themes and apporaches of First Nations poetry.

“By anchoring the project in relationality, Woven's foundation is about how we connect with each other and what we are prepared, as First Nation artists, to offer and receive. The emphasis was about (re)generating poetic First Nations bonds — solidarity, consensus, family, land, oceans, the moon, remembering, dreaming, sharing, opening, mourning, respect, celebrating, finding, losing, healing and more healing.” —Anne-Marie Te Whiu

Poet collaborations in the anthology: Linda Tuhiwai Smith & Jackie Huggins; Evelyn Araluen & Anahera Gildea; Alison Whittaker & Nadine Hura; Chelsea Watego & Emma Wehipeihana; Raelee Lancaster & essa may ranapiri; Ali Cobby Eckermann & Joy Harjo; Natalie Harkin & Leanne Betasamosake Simpson; Samuel Wagan Watson & Sigbjorn Skaden; Tony Birch & Simon J. Ortiz; Ellen Van Neerven & Layli Long Soldier; Lorna Munro & January Rodgers; Rhyan Clapham (aka Dobby) & Nils Rune Utsi (aka SlinCraze); Declan Fry & Craig Santos Perez; Bebe Backhouse-Oliver & Peter Sipeli; Jazz Money & Cassandra Barnett; Charmaine Papertalk Green & Anna Naupa.

Intervals by Marianne Brooker $32

What makes a good death? A good daughter? In 2009, with her forties and a harsh wave of austerity on the horizon, Marianne Brooker's mother was diagnosed with primary progressive multiple sclerosis. She made a workshop of herself and her surroundings, combining creativity and activism in inventive ways. But over time, her ability to work, to move and to live without pain diminished drastically. Determined to die in her own home, on her own terms, she stopped eating and drinking in 2019. In Intervals, Brooker reckons with heartbreak, weaving her first and final memories with a study of doulas, living wills and the precarious economics of social, hospice and funeral care. Blending memoir, polemic and feminist philosophy, Brooker joins writers such as Anne Boyer, Maggie Nelson, Donald Winnicott and Lola Olufemi to raise essential questions about choice and interdependence and, ultimately, to imagine care otherwise.

Listed for the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction.

”Intervals is an exceptional book, for which every deserved superlative seems cliched, in part because the language of illness, death and bereavement often feels too hollowed out by use to accommodate the magnitude of those experiences.… [W]ritten with such clarity and precision... this angry, loving, sorrowing and profound book is a magnificent starting point for [a] radical imaginative act.’” — Alex Clark, Observer

”Intervals is an endlessly moving and profoundly generous telling of what it means to give and receive care. Stunning in its intimacy and expansive in its political purpose, Brooker’s writing invites us to think deeply about the relationship between giving care and honouring life. Through visceral, tactile details of creating, working, making and tending, Brooker brings us into the spaces where caring happens, where life and its endings happen. A rare, revelatory, and truly radical book.” — Elinor Cleghorn, author of Unwell Women

The Britannias: An island quest by Alice Albinia $70

By looking more closely at the periphery we might learn something about the centre. The Britannias tells the story of Britain's islands and how they are woven into its collective cultural psyche. From Neolithic Orkney to modern-day Thanet, Alice Albinia explores the furthest reaches of Britain's island topography, once known (wrote Pliny) by the collective term, Britanniae. Sailing over borders, between languages and genres, trespassing through the past to understand the present, this book knocks the centre out to foreground neglected epics and subversive voices. The ancient mythology of islands ruled by women winds through the literature of the British Isles — from Roman colonial-era reports, to early Irish poetry, Renaissance drama to Restoration utopias — transcending and subverting the most male-fixated of ages. The Britannias looks far back into the past for direction and solace, while searching for new meaning about women's status in the body politic. Boldly upturning established (un)truths about Britain, it pays homage to the islands' beauty, independence and their suppressed or forgotten histories.

Long-listed for the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction.

”A dazzlingly brilliant book. Travelling by boat, swimming through kelp, riding on a fishing trawler, Alice Albinia takes us on an extraordinary journey around the British isles, revealing a liquid past where women ruled and mermaids sang and tracing the sea-changes of her own heart.” —Hannah Dawson

”There are books crafted from research, worthy and informative. And there are books that happen. That need to happen. That feel inevitable. As if they have always, somehow, been there waiting for us. The voyages of Alice Albinia around our ragged fringes range through time, recovering and resurrecting the most potent myths. A work of integrity and vision.” —Iain Sinclair

Bird Child, And other stories by Patricia Grace $37

Mythology and contemporary Māori life are woven together in this eagerly anticipated new collection from this beloved author. The titular story ‘Bird Child’ plunges you deep into Te Kore, an ancient time before time. In another, the formidable goddess Mahuika, Keeper of Fire, becomes a doting mother and friend. Later, Grace’s own childhood vividly shapes the world of the young character Mereana; and a widower’s hilariously human struggle to parent his seven daughters is told with trademark wit and crackling dialogue.

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: A Palestinian story by Nathan Thrall $40

Milad is five years old and excited for his school trip to a theme park on the outskirts of Jerusalem, but tragedy awaits — his bus is involved in a horrific accident. His father, Abed, rushes to the chaotic site, only to find Milad has already been taken away. Abed sets off on a journey to learn Milad's fate, navigating a maze of physical, emotional, and bureaucratic obstacles he must face as a Palestinian. Interwoven with Abed's odyssey are the stories of Jewish and Palestinian characters whose lives and pasts unexpectedly converge — a kindergarten teacher and a mechanic who rescue children from the burning bus; an Israeli army commander and a Palestinian official who confront the aftermath at the scene of the crash; a settler paramedic; ultra-Orthodox emergency service workers; and two mothers who each hope to claim one severely injured boy. A Day in the Life of Abed Salama is a deeply immersive, stunningly detailed portrait of life in Israel and Palestine.

”Shows humanity on both sides. The author writes coolly, carefully, without rhetoric or invective. He does not claim neutrality — the daily humiliations of Israeli occupation thud like a drumbeat on every page — but he avoids arm-twisting reportage or cartoonish history. No one portrayed here lacks humanity or complexity.” —Boyd Tonkin, Financial Times

”A compelling work of nonfiction, a book that is by turns deeply affecting and, in its concluding chapters, as tense as a thriller. Not only a meticulously detailed account of one event but perhaps the clearest picture yet of the reality of daily life in the occupied territories.” —Jonathan Freedland, Guardian

”Nathan Thrall's book made me walk a lot. I found myself pacing around between chapters, paragraphs and sometimes even sentences just in order to be able to absorb the brutality, the pathos, the steely tenderness, and the sheer spectacle of the cunning and complex ways in which a state can hammer down a people and yet earn the applause and adulation of the civilized world for its actions.” —Arundhati Roy

”The book combines heart-wrenching prose with rare political insight. It tells a deeply moving story about one tragic road accident, which illuminates the tragedy of the millions of Palestinians who live under Israeli Occupation.” —Yuval Noah Harari

Ordinary Human Failings by Megan Nolan $37

When we look beyond the headlines, everyone has a story to tell It's 1990 in London and Tom Hargreaves has it all: a burgeoning career as a reporter, fierce ambition and a brisk disregard for the "peasants” — ordinary people, his readers, easy tabloid fodder. His star looks set to rise when he stumbles across a scoop: a dead child on a London estate, grieving parents loved across the neighbourhood, and the finger of suspicion pointing at one reclusive family of Irish immigrants and 'bad apples': the Greens. At their heart sits Carmel: beautiful, otherworldly, broken, and once destined for a future beyond her circumstances until life — and love — got in her way. Crushed by failure and surrounded by disappointment, there's nowhere for her to go and no chance of escape. Now, with the police closing in on a suspect and the tabloids hunting their monster, she must confront the secrets and silences that have trapped her family for so many generations.

”A subtle, accomplished and lyrical study of familial and intergenerational despair, a quiet book about quiet lives... An excellent novel: politically astute, furious and compassionate. A genuine achievement.” —Guardian

Chinese Dress in Detail by Sau Fong Chan $65

Chinese Dress in Detail reveals the beauty and variety of Chinese dress for women, men and children, both historically and geographically, showcasing the intricacy of decorative embroidery and rich use of materials and weaving and dyeing techniques. The reader is granted a unique opportunity to examine historical clothing that is often too fragile to display, from quivering hair ornaments, stunning silk jackets and coats, festive robes and pleated skirts, to pieces embellished with rare materials such as peacock-feather threads or created through unique craft skills, as well as handpicked contemporary designs. A general introduction provides an essential overview of the history of Chinese dress, plotting key developments in style, design and mode of dress, and the traditional importance of clothing as social signifier, followed by eight thematic chapters that examine Chinese dress in exquisite detail from head to toe. Each garment is accompanied by a short text and detail photography; front-and-back line drawings are provided for key items. An extraordinary exploration of the splendour and complexity of Chinese garments and accessories.

French Boulangerie: Recipes and techniques from the Ferrandi School of Culinary Arts $65

A very clear and approachable complete baking course from the world-renowned professional culinary school École Ferrandi, dubbed the "Harvard of gastronomy" by Le Monde newspaper. From crunchy baguettes to fig bread, and from traditional brioches to trendy cruffins, this comprehensive volume teaches aspiring bakers how to master the art of the French boulangerie. This new cookbook focuses on bread and viennoiserie, the category of French baked goods traditionally enjoyed for breakfast (like croissants and pains au chocolat). The culinary school's team of experienced chef instructors provides more than 40 techniques, explained in 220 step-by-step instructions — from making your own poolish or levain to kneading, shaping, and scoring various types of loaves, and from laminating butter to braiding brioches. Base recipes for doughs, fillings, and classic viennoiserie provide fundamental building blocks. Organized into four categories — traditional breads, specialty breads, viennoiserie, and sandwiches — the 83 easy-to-follow recipes provide home chefs with sweet and savory options for breakfast or snacks--from country bread to grissini, pastrami bagels to croque-monsieurs, and kougelhopf to beignets. Includes gluten-free, vegetarian, and vegan recipes. A general introduction explains the fundamentals of bread and viennoiserie making, including key ingredients, the importance of gluten, the steps of fermentation, and an informative glossary.

Sophie’s World: A graphic novel about the history of philosophy, Volume 1: From Socrates to Galileo by Jostein Gaardner, adapted by Vincent Zabus and drawn by Nicoby $40

One day, Sophie receives a cryptic letter posing an intriguing question: "Who are you?" A second message soon follows: "Where does the world come from?" It is the beginning of an unusual correspondence between our curious young heroine and her mysterious penpal. As the questions begin to pile up, Sophie is propelled headlong into a startling adventure through the history of Western philosophy. Her search for answers will see her explore each of the major schools of thought, as she tries to uncover the true nature of the letters, her secretive teacher — and, above all, herself! In this witty comics adaptation, Zabus and Nicoby have reinvented Jostein Gaarder's novel of ideas to bring Sophie's exploration of meaning and existence to a whole new medium.

Traditional Lifeways of the Southern Māori by James Herries Beattie (edited by Atholl Anderson) $50

Journalist James Herries Beattie recorded southern Māori history for almost fifty years and produced many popular books and pamphlets. Traditional Lifeways of the Southern Māori is his most important work. This significant resource, which is based on a major field project Beattie carried out for the Otago Museum in 1920, was first published by Otago University Press in 1994 and is now available in this new edition. Beattie had a strong sense that traditional knowledge needed to be recorded fast. For twelve months, he interviewed people from Foveaux Strait to North Canterbury, and from Nelson and Westland. He also visited libraries to check information compiled by earlier researchers, spent time with Māori in Otago Museum recording southern names for fauna and artefacts, visited pā sites, and copied notebooks lent to him by informants. Finally he worked his findings up into systematic notes, which eventually became manuscript 181 in the Hocken Collections, and now this book. Editor Atholl Anderson introduces the book with a biography of Beattie, a description of his work and information about his informants. Beattie wrote a foreword and introduction to the Murihiku section, which are also included here.

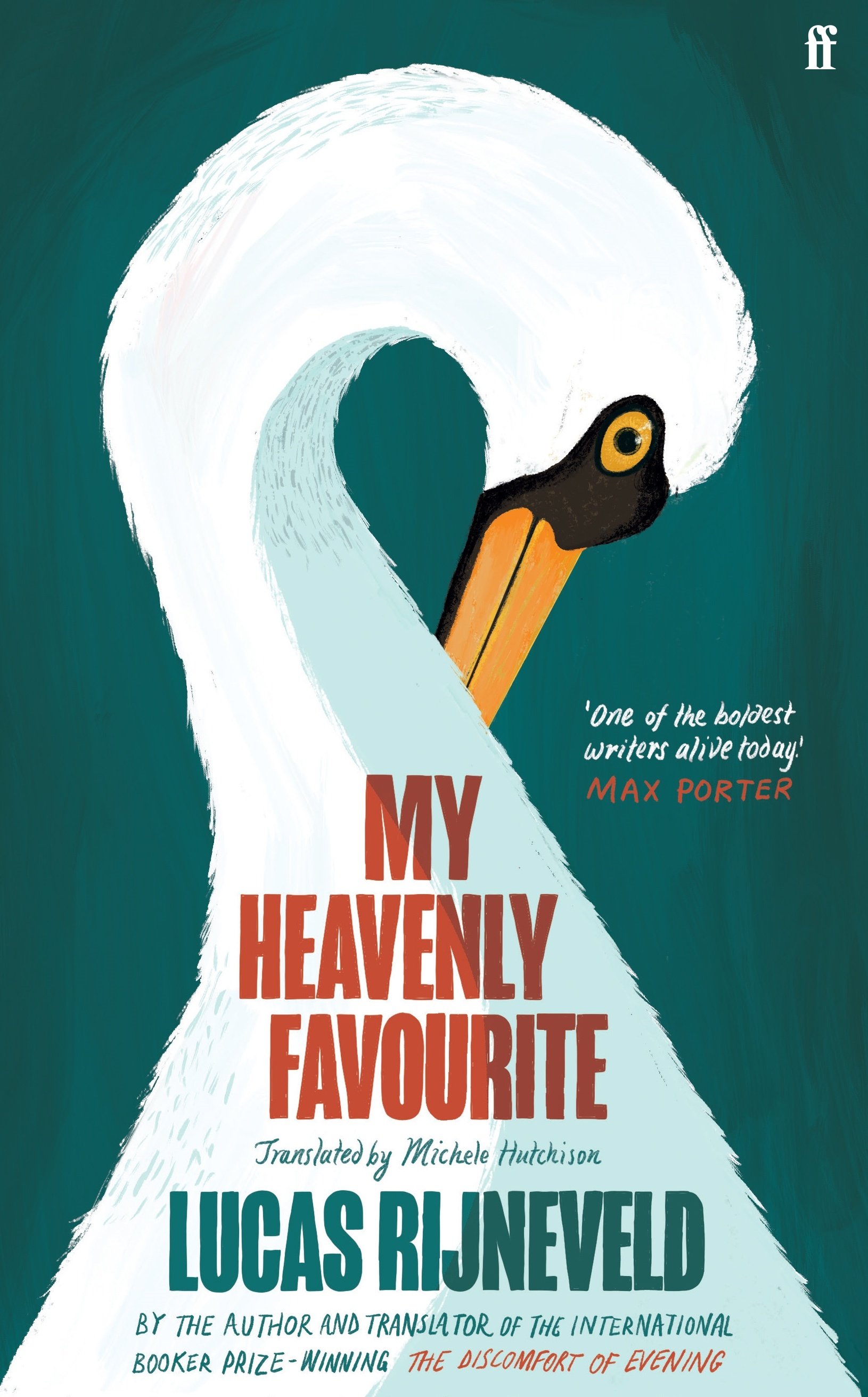

My Heavenly Favourite by Lucas Rijneveld (translated from Dutch by Michele Hutchison) $37

I heard you laughing from time to time and you stayed lying there on the flattened hay, and after you left, your body's imprint was left behind, and I rested my hand on the dry blades of grass that were still slightly warm and I wanted to carry on feeling you forever, really I did, but everything changed when you began to speak to me, on 7 July to be precise.

In the tempestuous summer of 2005, a 14-year-old farmer's daughter makes friends with the local veterinarian who looks after her father's cows. He has reached 'the biblical age of seven times seven' and is trying to escape trauma, while she is trying to escape into a world of fantasy. Their obsessive reliance on each other's stories builds into a terrifying trap, with a confession at the heart of it that threatens to rip their small Dutch community apart. From the author of the International Booker-winning The Discomfort of Evening.

”My Heavenly Favourite belongs to a tiny, controversial subgenre: novels about child sex abuse rendered in exquisite prose. It is all the more transgressive in that it’s narrated by the abuser, who addresses his victim in an incantatory, unflinchingly graphic second-person rant about his eternal love. Such a book has to clear a very high bar not to seem like a cynical exercise. Rijneveld’s novel leaps effortlessly over, with room to spare. What is truly extraordinary here is how, although the voice is Kurt’s, the ruling consciousness is Little Bird’s. … My Heavenly Favourite squares up deliberately to Lolita, citing it throughout, and Rijneveld compares well with Nabokov in the richness of his invention and the delicacy of his prose, while taking a much more serious approach to their shared subject. Indeed, Rijneveld conveys the squalor and despair of sexual violence with more fidelity than any other author I have read. But this novel is not only a surprisingly successful treatment of a difficult subject. It’s a unique creation and a tour de force of transgressive imagination – a dazzling addition to the oeuvre of an author of prodigious gifts.” —Sandra Newman, Guardian

Award-winning Albanian writer Ismail Kadare unpicks a three-minute conversation in thirteen views in his latest novel, A Dictator Calls. Here history, memoir, fiction, and myth merge to analyse a short and tense telephone conversation between Joseph Stalin and Boris Pasternak. Within these factual and imagined viewpoints Kadare probes the relationship between art and autocracy — how to write under a dictatorship — with verve and wit.

“An inquiry concerning power, artistic integrity, fame, memory and more. A Dictator Calls is slim, but its themes are not — the riddles of this novel are still ringing in my mind. “ —Sunday Telegraph

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Read our 369th newsletter.

23 February 2024

Spin the globe and choose a book! Find out what we’ve been reading!

The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands by Huw Lewis-Jones

What could be better than opening a new book to find a map of a yet-to-be-discovered world? If you were a child like me, you would have spent as many hours looking at the map and imagining yourself in it as you would have done reading (and re-reading) the book itself. From Milly Molly Mandy’s village — her home, the house that little friend Susan lived in, where they picked berries, the village green where the fete would be — to the land of Narnia through the wardrobe, maps in books were a key that opened a portal to the worlds beyond home, school and the dreariness of the ‘real’ world. Finding a Moomin book in the deaccessioned shelf at the public library was a discovery in itself, but that it included an amazing and delightful world, with a detailed map, was unforgettable. Maps still have that fascination and I never tire of atlases. There’s something about imagining oneself elsewhere. The Writer’s Map is a beautifully illustrated atlas of literary maps, edited by historian Huw Lewis-Jones, with accompanying insightful essays from writers, designers, and illustrators. They talk about the influence of maps on their own work, the importance of map-making in creating plot and place, and the wondrous spaces, emotional and physical, where maps have taken and continue to take them. Philip Pullman, the creator of Northern Lights, opens with an essay entitled 'A Plausible Possible', where he describes creating a map for a book he wrote called The Tin Princess. To create a plausible scenario for his princess, Adelaide, he needed a possible world where the plot could play out. Other authors in the book write about the relationship between map-making and fiction: David Mitchell sketches and draws maps for his books, even though these do not appear in the finished novels. There are examples from his private notebooks showing islands, mountain trails, and fortifications. “Maps of fictitious places are maps of mind. You lose yourself in them and find, if not factual truth, then other kinds.” Brian Selznick, the author/illustrator of several amazing books, remembers his fascination with the anatomy section of his Golden Encyclopedia, with its mapping of the human bodies, and all the pathways of connected systems played out with layered acetate sheets. As a ten-year-old, he had a major operation, one that he recovered slowly from. Drawing was his world and continued to be so. “We all end up drawing the maps to our own futures, though we usually don’t know it at the time.” The book is split into four sections, 'Make Believe', with introductory essays from Huw Lewis-Jones and Brian Sibley; 'Writing Maps', with author contributions; 'Creating Maps', with contributions from illustrators and designers; and Reading Maps. Many of the contributors draw on their childhood memories and their love of books and maps, and how these influenced their own work. References include Treasure Island, Middle-earth, Narnia, and Moomin Valley. They also outline their journeys as map-makers, storytellers, and creators of imaginary worlds. The Writer’s Map is lavishly illustrated and a pleasure to read. It will have you wanting to delve into an imaginary world immediately or to take up your pencil to draw your very own. Highly recommended for lovers of books and maps.

The Atlas of Unusual Borders by Zoran Nikolic

Here’s one for the curious and for those who love the strange histories of borders. Why are there odd pockets of land surrounded by another country? How did an action a thousand years old, possibly a whim, remain relevant and intact? Why do people with so much in common make life so complicated? And what happens when mistakes are made on paper? What are the stories behind the quirks of territorial demarcation? In this wonderfully fascinating book, Zoran Nikolic takes us into the world of enclaves and exclaves, the finer points of unusual geography, and the heady politics, as well as arbitrary nature, of borderlines. There are over 40 places, each with tales and maps, alongside snippets about island enclaves in rivers and lakes, ghost towns, border quadripoints, and unusual capitals. Where did I go first? To Cyprus, to discover a little more. While I knew that it is split in two — north and south — and that there was/is a UN buffer zone, and that there were British military bases there, I hadn’t realised the border implications of this beyond the obvious. At 9,250 square kilometres (that’s roughly the same size as Tasman region) the Mediterranean island consists of four political territories and numerous borders. There is a southern enclave in the north — a village mistakenly not occupied in 1974. And there is a Turkish village enclave in the south now with only a small Turkish garrison. The two British military bases are their own territories, with one of them split into two with a communications station in a nearby village connected by a narrow road of sorts — another strip of British territory. There is the ghost town, once luxury resort, of Varosia. The UN Green Line still exists but it is demilitarised and has a population of about 10,000 and a UN force of roughly 1000. It’s a semi-open buffer zone mostly used for farming, but retains elements of abandonment, and still plays a role in keeping the peace. Each place Nikolic takes us to has a story, quirky facts, and sometimes convoluted histories. There is the Bosnian wedding gift village that now sits in Serbia. They pay taxes to Bosnia, but utility bills to Serbia. There is the all-male population of Mt Athos and the man-made Oil Rocks industrial town in the middle of the sea. There is the German Green Belt which belongs to nature, and the Australian Island aptly named Border Island because the line runs right through it. It’s a rock in a windswept sea! Intriguing and endlessly diverting, this is an enjoyable book to lose yourself in, and discover something unusual.

These books have just arrived and are ready to be read.

Click through for your copies:

Out of Earth by Sheyla Smanioto (translated from Brazilian Portuguese by Laura Garmeson and Sophie Lewis) $45

This remarkable Brazilian novel follows four generations of female characters as they navigate the hardships of life in the parched landscape of the Brazilian sertao. Male figures are peripheral, but are also revealed as the origin of much of the suffering in the novel, generating for the women a kind of exile not only in relation to the land but to their sense of self. This is a ground-breaking feminist work, a bracing modernist fable, of sorts, formally reminiscent of A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing.

The Grimmelings by Rachael King $25

Thirteen-year-old Ella knows that words are powerful. So she should have known better than to utter a wish and a curse on the same day, even in jest. When the boy she has cursed goes missing, in the same sudden, unexplained way as her father several years earlier, Ella discovers that her family is living in the shadow of a vengeful kelpie, a black horse-like creature. With the help of her beloved pony Magpie, can Ella break the curse of the kelpie and save not just her family, but the whole community?

”Rachael King's The Grimmelings is one of those very rare books that feels like it has always existed, as if the world has been holding space for this story. With wonderfully assured writing, this is Susan Cooper for the next generation. King writes with the utmost respect for her readers, for the story and for language itself. The Grimmelings is a beautifully written story of old magic; uncontainable, unpredictable, wild and true — I could not put it down. And although the phrase is thrown around a lot, this genuinely is a future classic.” —Zana Fraillon

”The Grimmelings is a riveting adventure set on a horse-trekking farm in the lakeside wilds of the South Island of New Zealand, where lonely thirteen-year-old Ella, the granddaughter of a rumoured witch, finds herself the target of an ancient and vengeful water horse. Ella's courage, grief and grit make her a worthy protagonist; the reader cannot help but sympathise with and root for her as she fights to save her family from the saddle of her feisty pony, Magpie. Exquisitely crafted and thrumming with old magic, The Grimmelings wraps the reader like an heirloom quilt, stitched with glittering folklore, mysterious family secrets and the love of horses.” —Rachael Craw

”The Grimmelings is a compelling, lovingly crafted novel about magic, liminal spaces (of several kinds), language and folkloric fusion. Rachael King's characters live and breathe. Her dialogue glitters quietly. She discovers new perspectives in inherited narratives to create a world that is familiar yet unexpected, tense and eerie with flashes of beauty..” —David Mitchell

The Great Undoing by Sharlene Allsopp $40

How long can you run from a lie, if that lie is what your life is founded on? In a near future all identity information is encoded in digital language. Nations know where everyone is, all the time. Not everyone agrees with this constant surveillance, and when the system is hijacked and shut down, all global borders are closed. The world is no longer connected, and there is no back-up plan to establish belonging, ownership or trade. Scarlet Friday, whose job is to correct historical record, is stranded on the wrong side of the globe. Befriended by a stranger, she grabs an old, faded history book and writes her own version over the top — a record of the Great Undoing on the run. But in deciding what truth to tell Scarlet must face her own history. How do we navigate identity when it is all a lie? She must reckon with her past before she can imagine her future.

”For First Nations people, Australia is a nation founded on a lie. But this is not one single amorphous lie, but rather a web of lies that seeks to erase and make invisible First Nations peoples, her/histories and experiences. In her debut novel, The Great Undoing, Bundjalung author Sharlene Allsopp deftly juxtaposes the national and the personal mythscapes that still haunt Australia today. Through the larger-than-life character of Scarlet Friday, Sharlene explores the consequences of living a lie in a nation that refuses to acknowledge its past.” —Jeanine Leane

"Sharlene Allsopp's The Great Undoing is a remarkable book that reaches back into the early 20th century and forwards into the future to examine discontinuities in recorded histories, and the resonances of this within the lives of First Nations people. Allsopp's style is lyrical and almost poetic, even when describing ugliness. The Great Undoing joins the works of authors like Octavia Butler and Claire G Coleman, who use the light of what could be to illuminate what actually is.'“ —Books + Publishing

In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova (translated from Russian by Sasha Dugdale) $32

With the death of her aunt, Maria Stepanova is left to sift through an apartment full of faded photographs, postcards, diaries, and heaps of souvenirs: a withered repository of a century of life in Russia. Carefully reassembled, these shards tell the story of how a seemingly ordinary Jewish family managed to survive the last century. Dipping into various forms — essay, fiction, memoir, travelogue and historical documents — Stepanova's In Memory of Memory assembles a vast panorama of ideas and personalities and offers an entirely new and bold exploration of cultural and personal memory. New edition.

The Factory by Hiroko Oyamada (translated from Japanese by David Boyd} $33

Beyond the town, there is the factory. Beyond the factory, there is nothing. Within the sprawling industrial complex, three new employees are each assigned a department. There, each must focuses on a specific task: one shreds paper, one proofreads documents, and another studies the moss growing all over the expansive grounds. As they grow accustomed to the routine and co-workers, their lives become governed by their work — days take on a strange logic and momentum, and little by little, the margins of reality seem to be dissolving: Where does the factory end and the rest of the world begin? What's going on with the strange animals here? And after a while — it could be weeks or years — the three workers struggle to answer the most basic question: What am I doing here?

Innards by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene $37

Set in Soweto, the urban heartland of South Africa, Innards tells the intimate stories of everyday black folks processing the savagery of apartheid. Rich with the thrilling textures of township language and life, it braids the voices and perspectives of an indelible cast of characters into a breathtaking collection flush with forgiveness, rage, ugliness and beauty. Meet a fake PhD and ex-freedom fighter who remains unbothered by his own duplicity, a girl who goes mute after stumbling upon a burning body, twin siblings nursing a scorching feud, and a woman unravelling under the weight of a brutal encounter with the police. At the heart of this collection of deceit and ambition, appalling violence and transcendent love is the story of slavery, colonization and apartheid, and it shows in intimate detail how South Africans must navigate both the shadows of the recent past and the uncertain opportunities of the promised land.

”A gut punch of a collection...it astonishes as it reveals how malignant political forces can both ravage and vitalize the human spirit.” —New York Times

”An unforgettable debut that hits with all the force of the sun. Complex and breathtaking, Innards is a book haunted by apartheid's monstrous shadow and illuminated by the radiant talent of one of our generation's most original voices. Makhene writes like liberation should feel: transcendently.” —Junot Diaz

I Can Open It For You by Shinsuke Yoshitake $32

Akira has a problem: He is too small to open packages by himself. He still needs grown-ups to help him. But one day, perhaps one day soon, he'll be able to open so many things without anyone's help — and not just packages. When that time comes, he'll make amazing discoveries, help other epople to open things, and maybe even save the day with his new skills. There is so much to look forward to! With humor and wit, acclaimed author-illustrator Shinsuke Yoshitake explores a child's feelings about growing up: the push and pull of relying on parents while striving to learn and do things by yourself. Delightful.

Day by Michael Cunningham $38

April 5th, 2019: In a cozy brownstone in Brooklyn, the veneer of domestic bliss is beginning to crack. Dan and Isabel, troubled husband and wife, are both a little bit in love with Isabel's younger brother, Robbie. Robbie, wayward soul of the family, who still lives in the attic loft; Robbie, who, trying to get over his most recent boyfriend, has created a glamorous avatar online; Robbie, who now has to move out of the house - and whose departure threatens to break the family apart. And then there is Nathan, age ten, taking his first uncertain steps toward independence, while Violet, five, does her best not to notice the growing rift between her parents.

April 5th, 2020: As the world goes into lockdown the brownstone is feeling more like a prison. Violet is terrified of leaving the windows open, obsessed with keeping her family safe. Isabel and Dan circle each other warily, communicating mostly in veiled jabs and frustrated sighs. And beloved Robbie is stranded in Iceland, alone in a mountain cabin with nothing but his thoughts - and his secret Instagram life - for company.

April 5th, 2021: Emerging from the worst of the crisis, the family comes together to reckon with a new, very different reality - with what they've learned, what they've lost, and how they might go on.

”Unsparing and tender.” —Colm Tóibín

”A brilliant novel from our most brilliant of writers".” —Colum McCann

Collected Folktales by Alan Garner $23

A superbly told collection of familiar and unfamiliar British folktales from an author who has been breathing them throughout his long life, and drawing from them the inspiration for all his novels.

The Postcard by Anne Berest $40

January 2003. The Berest family receive a mysterious, unsigned postcard. On one side was an image of the Opera Garnier; on the other, the names of their relatives who were killed in Auschwitz: Ephraim, Emma, Noemie and Jacques. Years later, Anne sought to find the truth behind this postcard. She journeys 100 years into the past, tracing the lives of her ancestors from their flight from Russia following the revolution, their journey to Latvia, Palestine, and Paris, the war and its aftermath. What emerges is a thrilling and sweeping tale that shatters her certainties about her family, her country, and herself. At once a gripping investigation into family secrets, a poignant tale of mothers and daughters, and an enthralling portrait of 20th-century Parisian intellectual and artistic life, The Postcard tells the story of a family devastated by the Holocaust and yet somehow restored by love and the power of storytelling.

The Waste Land: A biography of a poem by Mathew Hollis $30

A century after its publication in 1922, T. S. Eliot's masterpiece remains a work of comparative mystery. In this gripping account, Matthew Hollis reconstructs the making of the poem and brings its times vividly to life. He tells the story of the cultural and personal trauma that forged the poem through the interleaved lives of its protagonists — of Ezra Pound, who edited it, of Vivien Eliot, who endured it, and of T. S. Eliot himself whose private torment is woven into the fabric of the work. The result is an unforgettable story of lives passing in opposing directions: Eliot's into redemptive stardom, Vivien's into despair, Pound's into unforgiving darkness. Now in paperback.

The Flow: Rivers, water and wildness by Amy-Jane Beer $25

On New Year's Day 2012, Amy-Jane Beer's beloved friend Kate set out with a group of others to kayak the River Rawthey in Cumbria. Kate never came home, and her death left her devoted family and friends bereft and unmoored. Returning to visit the Rawthey years later, Amy realises how much she misses the connection to the natural world she always felt when on or close to rivers, and so begins a new phase of exploration. The Flow is a book about water, and, like water, it meanders, cascades and percolates through many lives, landscapes and stories. From West Country torrents to Levels and Fens, rocky Welsh canyons, the salmon highways of Scotland and the chalk rivers of the Yorkshire Wolds, Amy-Jane Beer follows springs, streams and rivers to explore tributary themes of wildness and wonder, loss and healing, mythology and history, cyclicity and transformation. Threading together places and voices from across Britain, The Flow is an immersive exploration of our personal and ecological place in nature.

”A true masterpiece; generous, elegant, acute, tender and furious.” —Charles Foster

The City Beautiful by Aden Polydoros $24

Would you sacrifice your soul to stop a killer? Chicago, 1893. For Alter Rosen, this is the land of opportunity. Despite the unbearable summer heat, his threadbare clothes, and his constantly empty stomach, Alter still dreams of the day he'll have enough money to bring his mother and sisters to America, freeing them from the oppression they face in his native Romania. But when Alter's best friend, Yakov, becomes the latest victim in a long line of murdered Jewish boys, his dream begins to slip away. While the rest of the city is busy celebrating the World's Fair, Alter is now living a nightmare: possessed by Yakov's dybbuk, he is plunged into a world of corruption and deceit, and thrown back into the arms of a dangerous boy from his past. A boy who means more to Alter than anyone knows. Now, with only days to spare until the dybbuk takes over Alter's body completely, the two boys must race to track down the killer — before the killer claims them next.

"An achingly rendered exploration of queer desire, grief, and the inexorable scars of the past." —Katy Rose Pool

”With stark, poignant prose and an endearing main character, The City Beautiful is an entrancing and chilling tale that deftly analyzes complex themes of identity and assimilation. One-part historical fantasy, one-part gothic thriller, this genre-blending story has something for everyone." —Kalyn Josephson

KIndred: Recipes, spices and rituals to nourish your kin by Eva Konecsny and Maria Konecsny $55