Read our latest newsletter. Find out about some new cookbooks, and about a prepublication offer. Our ‘Fiction Reductions’ sale continues!

24 January 2025

Read our latest newsletter. Find out about some new cookbooks, and about a prepublication offer. Our ‘Fiction Reductions’ sale continues!

24 January 2025

The results of any laboratory testing for cell abnormality or antigen present as either positive or negative but the passage of time demonstrates the result categories to be four: true positive, false positive, false negative and true negative; or, rather, the results are either positive or negative and the cellular abnormality or antigen is either present or absent, but the two sets of two categories are not superimposed due to error margins, indeterminacy and ambiguity. What is seen and what actually is overlap only in the majority of instances. Every statement has its confidence undermined, largely due to the processes by which the statement is achieved. Girl at End is concerned with laboratory testing and is itself a form of laboratory testing even when not ostensible about laboratory testing, but, often, about music, if music is not itself a form of laboratory testing. Girl at End is a book about seeking confidence in precision but losing confidence because of uncertainty about that to which precision has been applied, precision being always more certain about its origins than its applications. Girl at End is an accumulation of data fields that may or may not represent that to which they are applied, however googlable the data in the data fields may be, data fields through which people move, impelled by whatever it is that impels people, not our concern, not knowable, not useful knowledge even if it were knowable, and as they move through the data field, the data, in constant movement, bounces off their surfaces, scattering, interpenetrating, both defining and concealing whatever, whoever, has entered the field. Only surfaces make any sense. Interference in the flow of text, for instance, is both a camouflage and a revelation. Depending on the nature of the test, the grooming of the data field, the flavour of the obsession, disparate entities may present as similar and similar as disparate. This both increases our dependence upon the tests and undermines our confidence in the tests. False positives. False negatives. What if these were in the majority? We would be liberated into indeterminacy while still clutching at the tests even though we would know these tests were less reliable than not. Our presence in the data field can produce nothing but ambiguity. Uncertainty is our signature, evidence of our presence in a field comprised of data, the more precise, the more detailed, the better. Girl at End is a “literature of exhaustion.” Northern Soul meets laboratory cytology: Girl at End is the interpenetration of the two. When one’s interest is not very interesting but just interesting enough to qualify as an interest and when one’s occupation is not very occupying but just occupying enough to qualify as an occupation, it is the interpenetration of the two, by virtue of the spinning of a turntable or a centrifuge, the interpenetration, the mixing, the mutual contamination, if we can think of it as contamination, that makes us more than either the so-called interest or the so-called occupation. Only when exhausted can we find respite. Lab-lit is best read clean and leaves no residue. “Girl at End is feeling so virtual. Branco speaks. Sheriff speaks. Branco speaks again.” What people say is only mouthed. The words are obscured by the words of the songs on the soundtrack that overwhelms the screenplay, songs from the past, incidentally, as all data is from the past, but the screenplay is vital to the TV show because without it no-one would know how to be or what was what, depending on whether the screenplay is prescriptive or descriptive, and this is itself by no means certain. The screenplay is perhaps after all no screenplay but the notebook of some alien uncertain of what is important enough to record. “Paul Sartre eats his bowl of chips. They don’t seem like anything. It’s like they’re imbued with nothing.”

“It’s the same thing time and time again, shamelessly, tirelessly. It doesn’t matter whether it’s morning or afternoon, winter or summer. Whether the house feels like home, whether somebody comes to the door to let me in. I arrive, and I want to stay, and then I leave.” All My Goodbyes is a novel for the restlessness in us all. Mariana Dimópulos’s protagonist is a young woman on the move. Leaving Argentina at 23 in an attempt to thwart her father’s ambitions and to escape the confines of what she sees as her predictable life, she heads to Madrid with the idea of being an ‘artist’, smoking hashish and hanging out, discussing ‘ideas’ with other travellers. After only a month, she is bored and on the move again, reinventing herself — being Lola or Luisa — whichever identity fits, being a tourist or a traveller, making new backstories, but never quite the truth. She is ambiguous to those she meets and, at times, to the reader also. We follow, or aptly, interact with her life over a decade as she swings between several European places — Madrid, Malaga, Berlin and Heidelberg to mention a few — and South America, washing up in rural Patagonia. The narrative is fractured as she relays her memories, skidding across one experience to the next and back again in a looping circuit, tossing us backwards and forwards in time. We are taken into conversations and thrown out again; we interact with those she has formed relationships with and ultimately said goodbye to. We see her as a traveller, tourist, voyeur, baker, shelf stacker, factory worker, farmhand. Upon this fractured narrative, a web is woven as we piece together the relationships that make her and break her — and always there is an impending sense of something or someone that will change her, a sense of threat with the axe taking centre stage. Dimópulos’s writing is subtle and agile. We do not mind being tossed on our protagonist's sea. In fact, we are curious. We love her late-night conversations with Julia in her kitchen, leaning up against the bench with the sleepy Kolya bunched up in his mother’s arms; we wonder when she will give in to the gentle charms of the scholar Alexander; and question why she is fascinated by the uber entrepreneur Stefan. We know, before it happens, that she will abandon them all, that her desire to leave is greater than her desire to stay. She travels full circle: we encounter her back in her homeland — still restless, still moving — living in the southernmost part of Patagonia. Working for Marco and his mother she finally finds a place to stop. Yet deceit and disaster settle here and take her onward and away, against her will and desire. Is she the architect of her own disaster, creating impossible situations? Her abandonment of people in her life is at times mutually beneficial, at other times cruel. Why does she not speak up, or face up to herself, when she could make a difference? Her riposte is always to leave — to turn her back. While the themes in this novel are restlessness, abandonment and departure, the writing, in contrast, is assured, subtly ironic, agile and so compelling that you will want to reread this — you will want to keep arriving.

NAOMI ARNOLD WALKS AOTEAROA!

Walking from Bluff, at the southern tip of the South Island, to Cape Reinga, at the northern tip of the North Island, award-winning journalist, and author of Southern Nights, Naomi Arnold spent nearly nine months following Te Araroa, fulfilling a 20-year dream. Alone, she traversed mountains, rivers, cities and plains from summer to spring, walking on through days of thick mud, blazing sun, lightning storms, and cold, starlit nights. Along the way she encountered colourful locals and travellers who delight and inspire her. This is an upbeat, fascinating, and inspiring memoir of the joys and pains found in the wilderness, solitude, friendship, and love.

NORTHBOUND: Four Seasons of Solitude on Te Araroa will be published in April, 2025.

Order now for a signed copy at a special price: a pre-publication discount of 10%.

Use the code WALK at the check-out if ordering through our website — or just email us to secure your copy. Offer ends March 12th.

Cookbooks come in many guises. From your go-to favourite every day to special-occasion-feasting recipe books. From reference books which give you the science of cooking and definitive descriptions of ingredients, to those that talk food and eating. They all excite our interest in food and give us more cooking knowledge. These four recent books all combine witty, informative and passionate writing with recipes and food experiences, celebrating the pleasure of food in life, and lives in food!

Australian dedicated, almost obsessive, foodie Virginia Trioli delivers lively asides and joyful reflections with A Bit on the Side. Here you will find the sweet, the sour, the bitter and the sharp, all infused with delight. A Bit on the Side revels in the small moments: the sauces that make the dish, the joy of the perfect side salad, the local ingredient and the bits stuffed inside. Dotted with recipes, foodie hints and plenty of storytelling Trioli celebrates the small bursts of flavour that give life joy and meaning.

'A humorous reminder that the smallest things often carry the biggest rewards.' BONNIE GARMUS

'Utterly delightful. Trioli's passion for life - and food, glorious food - crackles through every joyous page. A book so rare and so bloody well done.' TRENT DALTON

'Each page is full of zest, wit and joy; Virginia writes like an angel.' CHLOE HOOPER

What could be better? Art, cuisine, and famous writers! The Bloomsbury Group fostered a fresh, creative and vital way of living that encouraged debate and communication ('only connect'), as often as not across the dining table. Gathered at these tables were many of the great figures in art, literature and economics in the early twentieth century: E. M. Forster, Roger Fry, J. M. Keynes, Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf, among many others. The Bloomsbury Cookbook - Recipes for Life, Love and Art is part cookbook, part social and cultural history. Generously illustrated with artworks and photographs, filled with menus and recipes this is perfect for lovers of food, literature, art, and history.

'I need this book!' - Nigella Lawson

'Glorious ... a feast of eccentric detail' - New Statesman

'A window onto Bloomsbury via recipes, grocery lists, pantries, kitchens and, above all, dining tables' - Virginia Nicholson

Restuarant critic and award-winning writer Jay Rayner’s first cookbook! With sixty recipes that take their inspiration from restaurants dishes served across the UK and further afield, Nights Out at Home includes a cheat's version of the Ivy's famed crispy duck salad, the brown butter and sage flatbreads from Manchester's Erst, miso-glazed aubergine from Freak Scene, and instructions for making the cult tandoori lamb chops from the legendary Tayyabs in London's Whitechapel — a recipe which has never before been written down. Seasoned with stories from Jay's life as a restaurant critic, and written with warmth, wit and the blessing, and often help, of the chefs themselves, Nights Out at Home is a celebration of good food and great eating experiences, filled with irresistible dishes to inspire all cooks.

'Jay has a way with words, but he's also a dab hand in the kitchen. This book is not just a collection of food memories but also of recipes that make you want to roll up your sleeves and start cooking' MICHEL ROUX

A unique work of literary and culinary joie de vivre, part food memoir, part recipe book, French Cooking for One is Michèle Roberts' first cookbook, and a personal and quirky take on Édouard de Pomiane's ten-minute cooking classic. Once a food writer for the New Statesman, Roberts was born in 1949 and raised in a bilingual French-English household, learning to cook from her French grandparents in Normandy. Her love of food and cookery has always shone through in her novels and short stories.

From quick bites for busy days to sumptuous main courses for those who enjoy spending more time in the kitchen, the focus throughout this book is on dishes that are simple and fun to prepare, and results that are mouthwatering to contemplate and, of course, to eat. With over 160 delicious recipes, the majority of which are vegetarian, combined with piquant storytelling and feminist wit, French Cooking for One is a working cook's book with French flair, bursting with life and illustrated with the author's original ink drawings, full of charm and humour.

Levy invites the reader into the interiors of her world, sharing her intimate thoughts and experiences, as she traces and measures her life against the backdrop of the literary and artistic muses that have shaped her. From Marguerite Duras to Colette and Ballard, and from Lee Miller to Francesca Woodman and Paula Rego, Levy shares the richness of their work and, in turn, the richness of her own. Each short essay draws upon Levy's life, encapsulating the precision and depth of her writing, as she shifts between questions of mortality, language, suburbia, gender, consumerism, and the poetics of every day living.

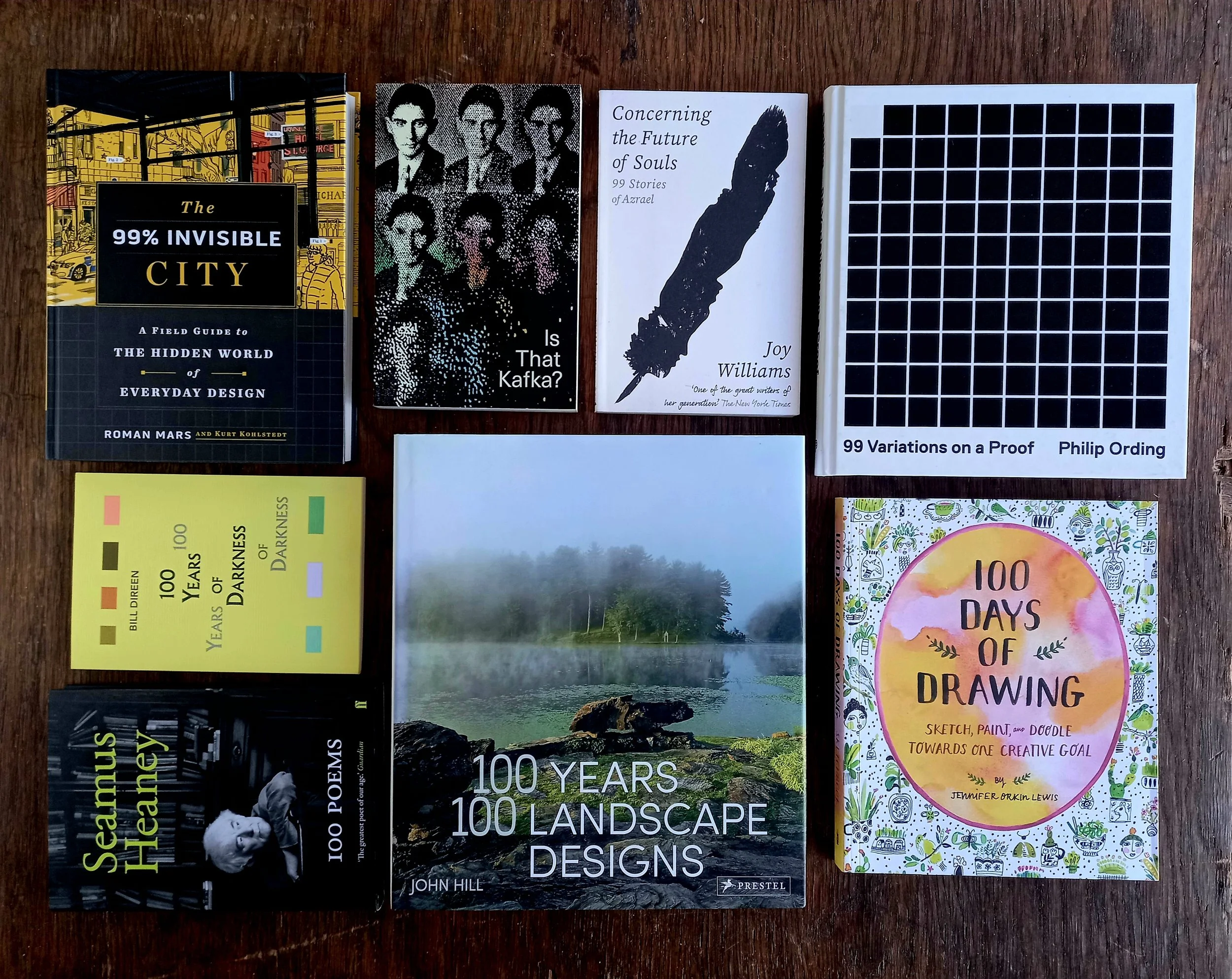

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Read our latest newsletter!

Our annual FICTION REDUCTIONS sale is the solution to your reading resolution!

17 January 2025

Be careful what you wish for! A catch-cry of our present time is a desire to find meaningful connection, to be part of a community within which we are specific and individual. Yet in reality we are more likely to find ourselves awash in a social media sea. In Jennifer Egan’s The Candy House, the desire for authenticity and connection is high and the clever Bix Bouton has the key. Bix is rich and successful. A fast-thinker graduate, his start-up, Mandala, took off, but now he’s out of ideas and craving something of the magic of his younger self. Infiltrating an academic discussion group where they are prying open the social anthropologist Miranda Kline’s theory Patterns of Affinity, kicks off the lightbulb for Bix. And the beautiful cube, Own Your Unconscious, is born. Get yourself a beautiful cube and download your memory — your every moment and feeling: either just for yourself so you can revisit childhood or recall a moment; or upload for the wider community — to The Collective Consciousness — so memories can be shared and information found (sound familiar?). Now Bix is richer, more successful, a celebrity who’s a regular at The White House and loved by many. Life is good. Yet at the edges there is doubt. And not everyone is a believer. There are eluders, those that wipe themselves to escape — pretty much losing their identity for freedom from the technological behemoth. There is Mondrian, an organisation that sees ethical problems within this set-up and offers a way out for those who feel trapped. This novel has connections to her Pultizer Prize-winning A Visit from the Goon Squad. There are characters who exist in both, and actions that are revisited by the curious, in particular the next generation who live with the consequences. There’s the anonymity of the urban and the claustrophobia of suburban landscapes, alongside the openness of the desert and the endless possibilities of the sea. All these landscapes play their role in the interior landscapes (the minds) of the diverse array of characters. This is a novel that does not stay still. There is no straight line in The Candy House. Egan writes explosive short pieces, chapters which connect, disconnect and reconnect (sometimes) in surprising ways. Characters are related in familial and relationship lines, or by deed, or the outsourced memory of deeds. Some we meet once, others on several occasions — they are in turn in all their guises: adults, children, parents, siblings. This may sound disjointed, and at times the narrative may lead you astray, but the thematic pulse runs continuously through. As in her earlier Goon Squad, Egan plays with structure and different narrative styles. There is the 'Lulu the Spy' chapter told in bite-sized dispatch commands — a tensely addictive reading experience; there is a brilliantly cutting e-mail conversation chapter where the narcissistic desires of the correspondents will make you wince; and there is the mathematically genius 'i, Protaganist' in which a man tries to realise his crush through obsessive statistical analysis. Knitted seamlessly into this wonderland of ideas are the concrete desires, fears and concerns of various humans, all achingly searching for authenticity within an illusionary world. An energetically clever novelist, Jennifer Egan’s The Candy House gives you sweet treats, as well as a whirlwind of sugary highs and lows. Put down the cube and pick up The Candy House.

To ‘stay’ in a hotel (as opposed to ‘staying’ home) does not mean to remain but merely to await departure. A hotel is not a home away from home but is the opposite of a home, a place where, as McBride puts it, “nothing is at stake,” a place where action and inaction begin to resemble each other, a place where the absence of context allows or invites unresolved pasts or futures to press themselves upon the present without consequence. There is no plot in a hotel; everything is in abeyance. The protagonist in Strange Hotel is present (or presented) in a series of hotels — in Avignon, Prague, Oslo, Auckland, and Austin (all hotels are, after all, one hotel) — over a number of years in what we could term her early middle age. She spends the narrated passages of time mainly not doing something, choosing not to sleep with the man in the room next door, not to throw herself from the window as she waits for a man to leave her room, not to stay in the room of the man with whom she has slept until he wakes up, not to meet a man at the hotel bar, not to let in the man with whom she has slept and who she almost fails to keep at the distance required by her rigour of hotel behaviour. Her ritual self-removal from the stabilising patterns of her ordinary existence — about which we learn little — in the hotels seems designed to reconfigure herself following the death of her partner without either wearing out the memory she has of him or being worn out by it. Slowly, through the series of hotels, she becomes capable of reclaiming herself from her loss, moving from instances where even slight resemblances to experiences associated with her dead partner close down thought (as with the speaker in Samuel Beckett’s Not I) to a point where memory begins to not overwhelm the rememberer, when the hold on the present of the past begins to loosen, when the path to grief loses its intransigence and coherence and no longer precludes the possibility that things could have been and could be different. McBride’s linguistic skill and introspective rigour in tracking the ways in which her protagonist negotiates with her memories through language is especially effective and memorable. Language is a way of avoiding thought as much as it is a way of achieving it: “Even now, she can hear herself doing it. Lining words up against words, then clause against clause until an agreeable distance has been reached from the original unmanageable impulse which first set them all in train.” Her self-interrogation and her “interrogating her own interrogation” “serves the solitary purpose of keeping the world at the far end of a very long sentence,” but as her ‘hotel-praxis’ (so to call it) starts to erode the structures of her ‘grief-taxis’ (so to call it), language is no longer capable of — or, rather, no longer necessary for and therefore no longer capable of — buffering her from loss: “I do like all these lines of words but they don’t seem to be helping much with keeping the distance anymore.” At the start of the the book she feels as if she has “outlived her use for feeling” and clinically observes that, in another, “sentiment must be at work somewhere, unfortunately”; in Prague she observes of the man whose departure from her room she awaits on the balcony: “She hadn’t intended to hurt his feelings. To be honest, she’s not even sure she has. His feelings are his business alone. She just wishes he hadn’t presumed she possessed quite so many of her own. She has some, naturally, but spread thinly around—with few kept available for these kinds of encounters.” By the end of the process, though — “to go on is to keep going on” — the possibility of feeling begins to emerge from beneath her grief, the present is no longer overwhelmed by actual or even possible alternative pasts, and she begins to sense that she can “turn too and return again from this most fitly resolved past that was never really an option — to the life which, in fact, exists.”

EXCELLENT FICTION AT GREATLY REDUCED PRICES. Make the discoveries that will reset and refresh your reading life.

Our annual fiction sale is the perfect way to stack up the solutions to your reading resolutions.

(Be quick: there are single copies only of most titles at these prices.)

Make 2025 your year of reading!

”Part of the beauty of the art of cooking is that it involves transience, making something delightful that then vanishes, and that in turn involves cherishing the time we spend on perfecting a dish. Cooking yourself something delicious is rewarding, satisfying, cheering. It makes us feel capable, creative, able to take care of ourselves. Cooking for yourself makes you feel spoiled and cherished.” —Michèle Roberts

A unique work of literary and culinary joie de vivre, part food memoir, part recipe book, French Cooking for One is Michèle Roberts' first cookbook, and a personal and quirky take on Édouard de Pomiane's ten-minute cooking classic. Once a food writer for the New Statesman, Roberts was born in 1949 and raised in a bilingual French-English household, learning to cook from her French grandparents in Normandy. Her love of food and cookery has always shone through in her novels and short stories. French cuisine, classic though it is, still holds delicious surprises. From quick bites for busy days to sumptuous main courses for those who enjoy spending more time in the kitchen, the focus throughout this book is on dishes that are simple and fun to prepare, and results that are mouthwatering to contemplate and, of course, to eat. With over 160 delicious recipes, the majority of which are vegetarian, combined with piquant storytelling and feminist wit, French Cooking for One is a working cook's book with French flair, bursting with life and illustrated with the author's original ink drawings, full of charm and humour. More than a handbook of classic French dishes, French Cooking for One also bears testimony to a singular literary life.

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Concerning the Future of Souls: 99 Stories of Azrael

…Reading, ready or not!

New books for a new year! Start as you mean to go on.

We can have your copies ready to collect from our door or dispatched by overnight courier.

The Pets We Have Killed by Barbara Else $35

In 1959 a schoolgirl is caught in the rivalry between two male teachers. In 1982 a New Zealander in her thirties is introduced to a snake in San Diego. In 2075 a government official drafts a summary of the first stage in NZ’s new-style elections. These eighteen stories mark Barbara Else’s return to fiction for adults. They are notable for their range in genre and tone, from realism to science fiction and fantasy, from subversive humour and sharp satire to thoughtful and humane contemplation of the human condition. Many are about romantic relationships — fresh and new, would-be, or long gone. All the stories demonstrate how the problems women face change little as time passes.

Granta 168: Significant Other edited by Thomas Meaney $37

Granta's summer issue is devoted to fictions of the 'other'. ‘Significant other' calls up the anodyne invitation from a host who wishes to strip away presumption. But we insist it is a fertile concept. Some significant others we know for much of our lives; others are meteoric: we may see them only once. Fiction includes J.M. Coetzee's story, 'The Museum Guard’, Victor Heringer's 'Lígia’ , and ‘Armance’ by Fleur Jaeggy. Introducing new fiction from Sophie Collins, Kevin Brazil, and Alexandra Tanner. Non-fiction features Mary Gaitskill's 'The Pneuma Method', James Pogue on the mines of Mauritania, and Susan Pedersen on paranormal love in the Balfour family. Christian Lorentzen appraises Daniel Sinykin's Big Fiction. Snigdah Poonam follows a teenager who makes a pilgrimage to Ayodhya, where the BJP's Hindu nationalists have built their dream temple of Ram. Poetry by Najwan Darwish, Zoë Hitzig, Tamara Nassar and Bernadette Van-Huy. Photography by Rosalind Fox Solomon (introduced by Lynne Tillman), Jesse Glazzard (introduced by Anthony Vahni Capildeo) and Debmalya Ray Choudhuri (introduced by John-Baptiste Oduor). Cover art by Simon Casson.

Bothy: In search of simple shelter by Kat Hill $45

Leading us on a gorgeous and erudite journey around the UK, Kat Hill reveals the history of these wild mountain shelters and the people who visit them. With a historian's insight and a rambler's imagination, she lends fresh consideration to the concepts of nature, wilderness and escape. All the while, Hill weaves together her story of heartbreak and new purpose with those of her fellow wanderers, past and present. Writing with warmth, wit and infectious wanderlust, Hill moves from a hut in an active military training area in the far-north of Scotland to a fairy-tale cottage in Wales. Along her travels, she explores the conflict between our desire to preserve isolated beauty and the urge to share it with others — embodied by the humble bothy. [Hardback]

”An intelligent and thoughtful book that will have you reaching for your boots. Hill offers learned and considered reflections on the consolations of retreat, simple living, of finding even temporary shelter when all outside is tempest. It is also a meditation on change: climate change, emotional growth, and the unquenchable nostalgia for a past slipping ever further from view.” — Cal Flyn

Hiroshima: The last witnesses by M.G. Sheftall $40

The stories of hibakusha - Japanese for atomic bomb survivors — lie at the heart of this compelling minute-by-minute account of 6 August 1945 — the day the world changed forever as the Enola Gay dropped its terrible payload over Hiroshima. These survivors and witnesses, now with an average age of over 90, are the last people alive who can still provide us with reliable and detailed testimony about life in Hiroshima before the bombings. In this heart-stopping account they relay what they experienced on the day the city was obliterated, and what it has been like to live with those memories and scars over the rest of their lives. M. G. Sheftall has spent years personally interviewing survivors who were just adolescents at the time but have lived well into their nineties, allowing him to construct portraits of what Hiroshima was like before the bomb, and how catastrophically its citizens' lives changed in the seconds, minutes, days, weeks, months and years afterwards. Fluent in spoken and written Japanese, his deep immersion in Japanese society has given him unprecedented access to the hibakusha in their waning years. Their trust in him is evident in the personal and traumatic depths they open up for him as he records their stories. [Paperback]

”M.G. Sheftall's Hiroshima presents as a master class in eyewitness storytelling. As poignant as it is powerful, this gripping narrative chronicles one of history's darkest nightmare moments-the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in August 1945-and the memories of its surviving eyewitnesses. As the events fade from living memory, Hiroshima is at once a brilliant tribute and a cautionary tale. “ —Annie Jacobsen

Fear: An alternative history of the world by Robert Peckham $33

Fear has long been a driving force — perhaps the driving force — of world history: a coercive tool of power and a catalyst for radical change. Here, Robert Peckham traces its transformative role over a millennium, from fears of famine and war to anxieties over God, disease, technology and financial crises. In a landmark global history that ranges from the Black Death to the terror of the French Revolution, the AIDS pandemic to climate change, Peckham reveals how fear made us who we are, and how understanding it can equip us to face the future. [Paperback]

”Brilliant and breathtakingly wide-ranging. As Peckham shows in gripping and beautifully written detail, fear isn't just the stock in trade of wicked despots; in some circumstances it can be turned to positive effect. Could it, now, be that fear is our friend? Read Peckham and judge for yourself.” —Simon Schama

The Lantern of Lost Memories by Sanaka Hiirage $25

In Mr Hirasaka's cosy photography studio in the mountains between this world and the next, someone is waking up as if from a dream. There is a stack of photos on their lap, one for every day of their life, and now they must choose the pictures that capture their most treasured memories, which will be placed in a beautiful lantern. Once completed, it will be set spinning, and their cherished moments will flash before their eyes, guiding them to another world. But, like our most thumbed-over photographs, our favourite memories fade with age. So each visitor to the studio has the chance to choose one day to return to and photograph afresh. Each has a treasured story to tell, from the old woman rebuilding a community in Tokyo after a disaster, to the flawed Yakuza man who remembers a time when he was kind, and a strong child who is fighting to survive. [Paperback]

Her Secret Service: The forgotten women of British intelligence by Claire Hubbard-Hall $40

Since the inception of the Secret Service Bureau back in 1909, women have worked at the very heart of British secret intelligence, yet their contributions have been all but written out of history. Now, drawing on private and previously-classified documents, historian Claire Hubbard-Hall brings their gripping true stories to life. From encoding orders and decrypting enemy messages to penning propaganda and infiltrating organisations, the women of British intelligence played a pivotal role in both the First and Second World Wars. Prepare to meet the true custodians of Britain's military secrets, from Kathleen Pettigrew, personal assistant to the Chief of MI6 Stewart Menzies, who late in life declared 'I was Miss Moneypenny, but with more power', to Jane Archer, the very first female MI5 officer who raised suspicions about the Soviet spy Kim Philby long before he was officially unmasked, and Winifred Spink, the first female officer ever sent to Russia in 1916. Hubbard-Hall rescues these silenced voices and those of many other fascinating women from obscurity to provide a definitive account of women's contributions to the history of the intelligence services.

The First Friend by Malcolm Knox $38

Even the worst person has a best friend. A chilling black comedy, The First Friend imagines a gangster mob in charge of a global superpower. The Soviet Union 1938: Lavrentiy Beria, 'The Boss' of the Georgian republic, nervously prepares a Black Sea resort for a visit from 'The Boss of Bosses', his fellow Georgian Josef Stalin. Under escalating pressure from enemies and allies alike, Beria slowly but surely descends into murderous paranoia. By his side is Vasil Murtov, Beria's closest friend since childhood. But to be a witness is dangerous; Murtov must protect his family and play his own game of survival while remaining outwardly loyal to an increasingly unstable Beria. The tension ramps up as Stalin's visit and the inevitable bloodbath approaches. Is Murtov playing Beria, or is he being played? The First Friend is a novel in a time of autocrats, where reality is a fiction created by those who rule. It is at once a satire and a thriller, a survivor's tale in which a father has to walk a tightrope every day to save his family from a monster and a monstrous society. Where safety lies in following official fictions, is a truthful life the ultimate risk?

”Crackling with energy, irony, wit and terror, The First Friend is a timely and cautionary reminder of the stifling, murderous logic of strong man politics.” —Tim Winton

“Razor-sharp, wildly imaginative, bold, brilliant and often as dark as the inside of a coffin. Another triumph from a truly extraordinary writer.” —Trent Dalton

“The First Friend is not just a cracking read, it's a masterclass in Machiavellian manoeuvres. This is a magnificent piece of gallows humour, bitingly funny and horrifyingly grim at the same time.” —Kate McClymont

”Bleak, intelligent and fearsomely well-researched — I kept telling myself I shouldn't laugh, but couldn't help it.” —Michael Robotham

War of the Worlds, A graphic novel by H.G. Wells and Chris Mould $45

In 1894, across space, this earth was being watched by envious eyes, and plans were being drawn up for an attack. What seems to be a meteorite falls to earth, but from the debris, unfolds terrifying alien life. A young man called Leon records his observations and sketches. “Those who have never seen Martian life can scarcely imagine the horror,” he tells us. “Even at this first glimpse, I was overcome with fear and dread. The earth stood still as we watched, almost unable to move.” As war descends, Leon and his scientist wife race against the clock to discover the science behind these Martians in the hopes of ending this war of all worlds. [Hardback]

”The exquisite, detailed illustrations convey as much emotion as do words in this remarkable re-imagining of War of the Worlds.” —Susan Price

”An absolute masterpiece.” —Kieran Larwood

A bit on the Side: Reflections on what makes life delicious by Virginia Trioli $40

Virginia Trioli knows that enduring joy is often found not in the big moments but in the small. And as a dedicated, almost obsessive, foodie, she believes that food gives us the perfect metaphor for how to seek, recognise and devour the real flavour of life. When the main course is heavy going or unappetising, the 'bits on the side' make life really delicious. The sweet and the sour; the salty, the bitter - our small, meaningful selections are the ones that make life glorious. A Bit on the Side is an ode to joy, filled with wisdom, stories, memories and recipes. [Hardback]

”A warmly engaging epicurean masterclass on the pleasures of companionship and the table.” —Christos Tsiolkas

When the Bulbul Stopped Singing: A diary of Ramallah under siege by Raja Shehadeh $25

The Israeli army invaded Palestine in April 2002 and held many of the principal towns, including Ramallah, under siege. A tank stood at the end of Raja Shehadeh's road; there were Israeli soldiers on the rooftops; his mother was sick, and he couldn't cross town to help her. Shehadeh kept a diary. This is an account of what it is like to be under siege: the terror, the frustrations, as well as the moments of poignant relief and reflection on the crisis gripping both Palestine and Israel. [New paperback edition]

”In his moral clarity and baring of the heart, his self-questioning and insistence on focusing on the experience of the individual within the storms of nationalist myth and hubris, Shehadeh recalls writers such as Ghassan Kanafani and Primo Levi.” —New York Times

”A buoy in a sea of bleakness.” —Rachel Kushner

Scandinavian Design by Charlotte and Peter Fiell $55

Scandinavia is world famous for its inimitable, democratic designs which bridge the gap between craftsmanship and industrial production, organic forms and everyday functionality. This all-you-need guide includes a detailed look at Scandinavian furniture, glass, ceramics, textiles, jewelry, metalware, and product design from 1900 to the present day, with in-depth entries on 125 designers and design-led companies. Featured designers and designer-led companies include Verner Panton, Arne Jacobsen, Alvar Aalto, Timo Sarpaneva, Hans Wegner, Tapio Wirkkala, Stig Lindberg, Finn Juhl, Märta Måås-Fjetterström, Arnold Madsen, Barbro Nilsson, Fritz Hansen, Artek, Le Klint, Gustavsberg, Iittala, Fiskars, Orrefors, Royal Copenhagen, Holmegaard, Arabia, Marimekko, and Georg Jensen. [New hardback edition]

Songlight by Moira Buffini $33

They are hunting those who shine. Don't be deceived by Northaven's prettiness, by its white-wash houses and its sea views. In truth, many of its townsfolk are ruthless hunters. They revile those who have developed songlight, the ability to connect telepathically with others. Anyone found with this sixth sense is caught, persecuted and denounced. Welcome to the future. Lark has lived in grave danger ever since her own songlight emerged. Then she encounters a young woman in peril, from a city far away. An extraordinary bond is forged. But who can they trust? The world is at war. Those with songlight are pawns in a dangerous game of politics. Friends, neighbours, family are quick to turn on each other. When power is everything, how will they survive? An impressive start to a new YA series. [Paperback]

Read our first newsletter of the new year and find out what we’ve been reading. Make your reading resolutions, and start as you mean to go on.

10 January 2025

A decade ago Ta-Nehisi Coates won the National Book Award with the powerful and profound Between the World and Me. Now he steps outside of American history to confront nationalism, what we think of as truth, and the power of story-telling. The Message, started as a letter to his students on writing, in the style of George Orwell’s essay ‘Politics and English Language’, but soon become something deeper and more personal. Coates uses his personal experiences; his relationships with his parents, his travels to Senegal to connect with his ancestry, his connection with a school teacher in South Carolina to counter the banning of books (his included), and a visit to Palestine in 2023 which broke assumptions he held; to grapple with ideas about the power of stories and how that shapes our concept of reality. The beauty of Coates’s thinking and writing lies in his ability to write for the reader, as he says, ‘to put blood on the page’. He does not seek popularity nor to adhere to prescribed notions, nor does he seek to explain all aspects of a people’s history, making this book, The Message, tightly focused on the addressing, and challenging, concepts of structures, and the ways in which structures dictate the stories we believe and keep power in the hands of oppressors. Written at a dramatic moment in global life, this work eloquently expresses the need to interrogate our myths and liberate our truths.

“Brilliant and timely . . . Coates presents three blazing essays on race, moral complicity, and a storyteller's responsibility to the truth. . . . Coates exhorts readers, including students, parents, educators, and journalists, to challenge conventional narratives that can be used to justify ethnic cleansing or camouflage racist policing.” —Booklist (starred review)

”Ever since his Baldwin-inflected Between the World and Me, Coates has been known for his incisive (and sometimes uncomfortable) cultural and political commentary. Here he journeys from West Africa to the American South to Palestine to examine how the stories we tell can fail us, and to argue that only the truth can bring justice.” —The Boston Globe

Find out more:

What to do when you’re read all of one of your favourite author’s books and there is nothing new on the horizon? Go backwards, of course! When you discover a writer you enjoy, it is usually somewhere mid-stream in their writing journey. They have risen to the top of the publicity machine, or cracked the bestseller list. Or you’ve discovered them via a friend’s or bookseller’s recommendation. Maybe they have made it through the distribution chain, been spied by a bookseller, landed on a shelf, and made it to your hand almost unbidden. Possibly you noted a review or were taken by the jacket design. Whatever myriad way in which you discover new authors, it’s bound to be somewhere in the midst of their writing career. (Unless they are a one-hit wonder!) So going backwards, when forwards is not an option, is often a possibility and adds context to what has come after. I thoroughly enjoy Sheila Heti’s writing. While I appreciate her obvious knowledge of literature and her skill with language, it is her curiosity which is most endearing. A curiosity with her own psyche and with writing as an experiment as well as an experience, paired with her sly wit, make her books thought-provoking and enjoyable. Her work starting with How Should a Person Be? (not her first published work — somewhere in the middle) is based on herself or a fictionalised idea of Heti. One can never be too sure about reality with Heti, but many of her books are described as ‘novels’. Her books are equal parts hilarious, earnest, infuriating, heartfelt, and compelling. This range of responses can be raised on a single page sometimes, and maybe this is what makes her work so interesting. So, to going backwards…

Ticknor, initially published in 2005, is a historical novel of sorts. Inspired by the real-life friendship between the American historian William Hickling Prescott and his biographer, George Ticknor, it’s a novella exploring friendship and scholarly society. Don’t let the unfamiliar names put you off. I knew nothing about these fellows, and it didn’t matter. Ticknor is a study in envy. And also an exercise in form. It’s been compared with Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser, and garnered a bit of attention in literary circles when it was published. And here is one literary circle where the bonds of a one-sided friendship has no opening. For Ticknor, this is a closed circle, one which means more to him than he does to his fellow writers. While his childhood friend climbs the ranks of fame and fortune, Ticknor becomes increasingly psychologically distraught and paranoid. A bitterness seeps in much like the rain that wets him through as he stands outside Prescott’s house deliberating his attendance at a dinner party to the point where it is too late to venture inside! Here is Ticknor, hardly likable, and here are his cronies, even less likable and disagreeably pompous. And yet, this is what Ticknor aspires to, inclusion and feted admiration. Should we sympathise? Heti balances our hand and heart with Ticknor’s absurdities and the ludicrous situation of scholarly jealousies. Here humour, her sly wit, come to the fore, and paired with the taut writing, make Ticknor, the novel, a worthy contender, while Ticknor, the man (in this fictional telling) not a contender at all. This novella isn’t the best of Heti’s work, but I enjoyed the stylitsic form and playful pointedness, and the wit keeps you there. Heti’s writing is always pushing at possibilities and exploring new ways to tackle the novel as form, as well as exploring how we live in the world. Her latest book, Alphabetical Diaries, is a case in point. Experimental work that is amusing, and rich with ideas and curiosity.

He began to think, on the first day of the year, that a sixty-year audit of some sort was now unavoidable even if it was also undesirable, even though he was generally fairly successful at avoiding whatever he deemed undesirable (most things, in fact). He had lately been finding himself increasingly reluctant to do even those things that he certainly wanted to do. He had made avoidance his life’s work, he realised: he had started by avoiding things that were both undesirable and unnecessary, and then moved through avoiding things that were either undesirable but necessary or desirable but unnecessary, and he was currently exercising his avoidance on things that were certainly both desirable and necessary. Why was he doing this? Where would it end? Also, he thought, since when has avoidance become my life’s work? I must have had, or thought I had, some other purpose at some point, or if not purpose then intention or at least inclination, he thought, but my avoidance has been all too effective with regard to something that was not even a necessity, or at least became less of a necessity as I got better at it. He was, he estimated, being soft on himself, at least twenty years behind where his writing would be if his writing was more important to him. Evidently it was less important now than it had been, he realised, otherwise surely he would spend more time actually doing it, or if not actually doing it actually trying to do it. Avoidance was more his line. True, he had avoided writing any number of bad books, more bad books than many accomplished writers had avoided writing, but he wasn’t sure if this was an accomplishment in itself. Being a writer meant that it was always writing that he was not doing, as opposed to all of the other many things that he was also not doing. There were, of course, many fortunate people who did even less writing than he did but it was not for them specifically writing that they were not doing, which must be a relief to them, he thought. So, if he stopped avoiding writing, if he replaced some of the other many things that he did in his life presumably to avoid writing with actual writing, could he make up the twenty years of work that he had just estimated he had lost? If he did this year for year, he estimated, he would be where he could have been now when he got to be the age of Joy Williams, the author of the book that he was reading when he began what has turned out after all to be a sort of involuntary audit. This is encouraging, he thought, but then, he thought, Joy Williams has been on some sort of plateau for well more than twenty years, or if not a plateau then a shallower incline than the one that certainly lay ahead of him and for which he doubted that he had now either the stamina or the strength to ascend. If I write metaphors, I cross them out straight away, he thought, but how can I cross out a thought? Few of the ninety-nine stories in Joy Williams’s Concerning the Future of Souls are more than a page long; many are a single paragraph or even a single sentence. As with the book’s 2016 predecessor, Ninety-Nine Stories of God, the stories in this new book, which is subtitled 99 Stories of Azrael, are written with a spareness and flatness that he admires, in the language of a newspaper report or an encyclopedia entry, trimmed utterly of superfluities, and read like jokes that end up making us cry instead of laugh, or like laments that make us laugh instead of cry. Williams comes at her subjects at unexpected angles, he thought, revealing an inherent strangeness in what we might have thought to be the most ordinary details, and, conversely, making the most bizarre details seem entirely familiar and mundane. Really, he thought, life is like this, in both ways, though we blind ourselves to this as best we can. Joy Williams has the literary gift of being able to shake these scales from our eyes. He had sworn off metaphors decades ago, even metaphors in thought, but sometimes they just sneak out. More than several of the stories in the book concern Azrael, the so-called Angel of Death, who is not Death nor the cause of death, but is more a reluctant functionary, updating the register of the living, writing and erasing the names of the living and helping the souls to move on. But where to? The proximity of an extinction event, so to call it, either or both personal and collective, for the author, for the reader, for everyone and everything, adds a sort of urgency to these stories that makes us hyperaware of each detail as we are in any developing tragedy or disaster. The most tragic is the most ludicrous too, he thought, and vice versa. A good piece of literature has the same effect upon our awareness as a disaster. The 99 stories in this book have the texture of Biblical parables or Aesopian fables, he thought, but they are not parables or fables due to the indeterminacy of their meanings, or they are parables or fables that eschew the lessons and morals usually expected of parables or fables and return the reader instead to the actual. What more could we want from a story? What more could we really want full stop? The title of each story follows the story and often sits at odds with the reader’s experience of the story, forcing a further realignment of sensibilities, he thought. More, again, of what we want. Of what I want. How can such an immense knowledge, experience and learning be packed by Williams into something so simple and immediate, the weight of existence into something so astoundingly light? How can we have time, especially nowadays, for anything that falls short of this? The urgency is upon us all, he thought, or at least he felt it upon himself, and he was uncertain how to respond. Should he perfect his avoidance, or should he clutch, too late, perhaps almost too late, at whatever it was he was attempting to avoid?

HE CANNOT TELL AN AUDIT FROM A REVIEW

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

The festive season is the time for good food and good company. In some households, along with the holiday feasting at Christmas and New Year, there are summer birthdays! So baking is in demand, and while the kitchen may be hot, the temperature is perfect for raising doughs and keeping butters soft. While we can fall back on our true and tested recipes, it’s also wonderful to bring new friends to the mixing bowl. And what better companion than Magnus Nilsson and his Nordic Baking Book. I never feel confident baking cakes, so there is always a degree of trepidation, especially when it is a special birthday. Delving into Nilsson’s book, his recipes and writing about baking, are both precise and relaxed. The sense of humour dotted through the writing and the sureness of approach adds confidence to your baking. I turned to the sponge recipes (of which there are several), read through his explainer on types of cake, and took his advice choosing his go-to recipe for layer cakes. The sponge batter was generous, so I made three, rather than two small sponges, without thinking about the consequences. The planned 3-layer cake became 5! So double the macaroon and more syrup to keep the cake moist! I retreated to the true and tested for the macaroon layers (an excellent Lois Daish recipe), and concocted my own orange and cardamom syrup. (A citrus-flavoured cake was requested.) My vanilla custard cream wasn’t perfect, but good enough.

There is something quite delightful about designing a cake and stacking the elements of a layer cake. And when it all comes together, depsite the trepidation pre-making and the fear of the cake slanting sideways or collapsing post-assembly, it is quite a thing to behold, as well as eat!

Orange & Cardamom Layer Cake