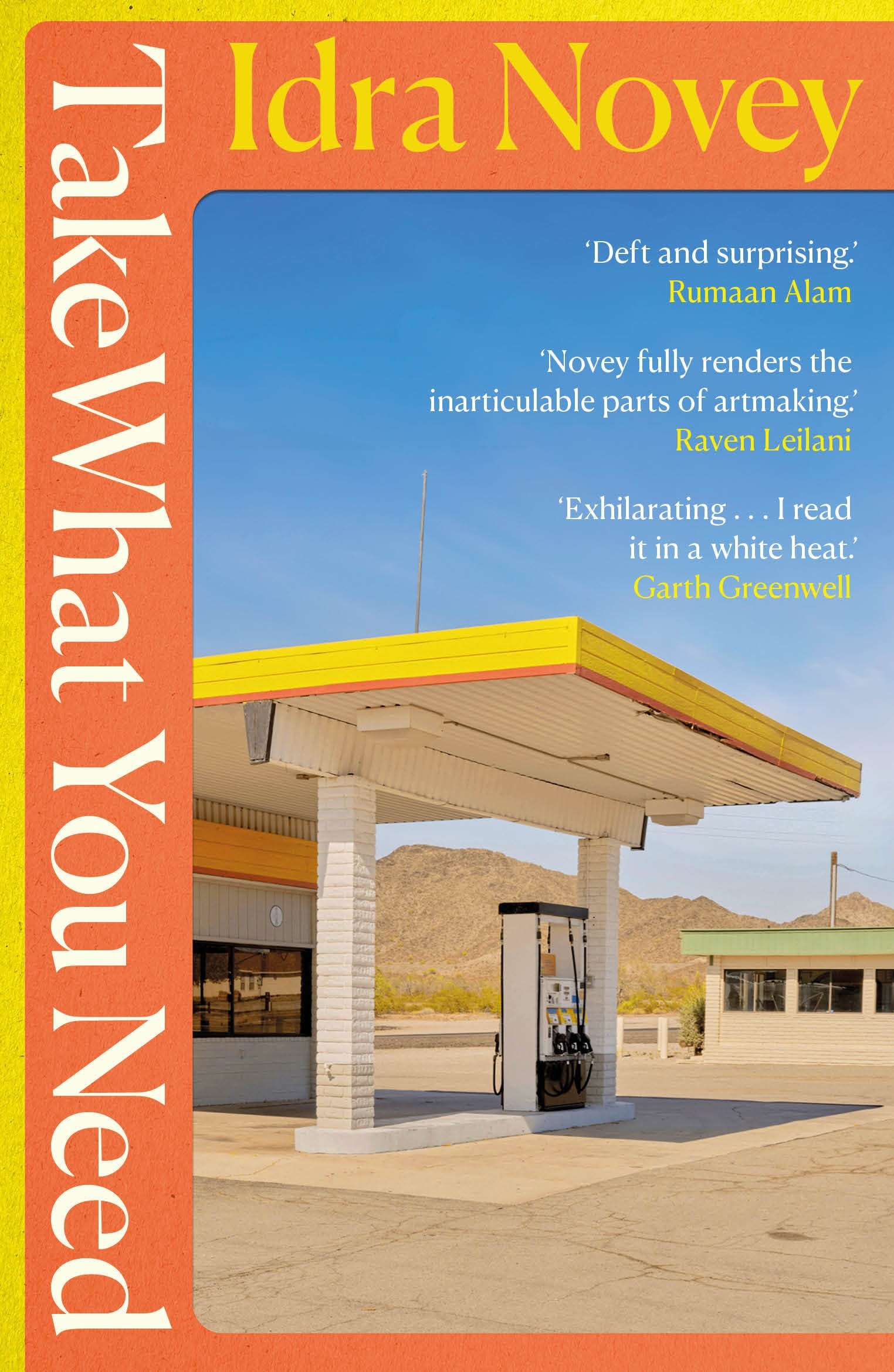

I’ve had this one on my ‘to read’ pile for a while. Attracted by the generic-service-station cover image, and the fact that this is published by Daunt Books, who pick up on some interesting titles not widely available outside their country of origin; a quick read of the blurb convinced me I needed to read this one. Set in the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia, it’s the story of Jean, her life in a rundown rust belt town (which isn’t going to see better days), her use of industrial materials to make sculptural structures, her almost solitary lifestyle, and her grief at being estranged from her step-daughter, Leah. It’s also Leah’s story — her coming to terms with her feelings for Jean, as well as her anger, through their shared, if broken, history, and Jean’s ‘manglements’. The Manglements are Jean’s massive towers welded from scrap metal plate, decorated with quirky junkyard and market table finds, all holding meaning and often humour, filling the downstairs of her rundown house, pressuring the floor and breathing into that space. Weave into this Jean’s awkward and unexpected relationship with Elliot, deliberately kept ambiguous by the author, but who becomes the vehicle for reconciling Leah with Jean, post-death; and whose character represents the despair and poverty of an abandoned community, Take What You Need explores the impact people have on each other, how an environment, emotionally and physically, shapes a person, and the driven passion for art that can illuminate a life. Here are Louise Bourgeois and Agnes Martin, two fellow reclusive and determined travellers, whispering in Jean’s ear. Here is the singular passion, as well as her cantankerous nature, that allows Jean to create, to follow her own path in spite of doubt, injury and risk, and an embattled, increasingly bitter and xenophobic community. And for Leah, a reckoning — a recognition of love, the importance of our childhoods and how they shape us in spite of ourselves, and a responsibility to step outside her own perspective to see everything that is good in a life’s work.

When your cat looks at you like you’ve done her a disservice by not sharing your Friday night snacks, despite the fact they are not cat treats, you realise that the cat has tipped into personhood. No longer just a cat, but a person leveling a malevolent stare at you and eyeing up your glass of ginger beer. (Lucy doesn’t like ginger beer, but has been known to sneak a sip at a cup of tea.) (1)

In Anna Jackson’s wonderful prose poem her hens feature throughout: their hen-ness evident on the page, and their personhood developing as the relationship between bird and human develops. But this is not an ode to hens, rather there are questions about what we think about when we think about (2) hens or contemplate our relation with domestic pets or our wider connection with nature. Don’t be misled for this is not nature writing, but then again it could be. (3) This is not a domestic poem, but it also is: — Jackson’s home and the familial feature on the page throughout the five seasonal sections. There is an autobiographical thread: Jackson’s thinking, her thoughts, the central cadence.(4). Yet this is not inward gazing, not a personal diary, rather a nod to diarists and keepers of memories. (5). And yet saying this I recall the poems about social anxiety, about uncertainty, about knowing. So I find myself saying it is a diary of sorts after all. Time plays its role. The collection is arranged by its five parts — five seasons — we travel from one summer to another. The ebb and flow not only being about time, but about the way thoughts arise and dissipate; how words work on the page, how poetry comes into being. Jackson’s reading (6) of other poets, essays, novels, non-fiction, philosophy mingle with her thoughts: — knowledge like residue landing in interesting places. Some profound, others extremely funny.(7). Terrier, Worrier: A poem in five parts is a deeply enjoyable and intelligent collection of thought-work and poetic good measure. It is as much about the idea of thoughts, of thinking, as it is about the thoughts themselves. Brilliant!

Notes:

1. Anna Jackson wrote these poems with a cat sitting on her lap.

2. This makes me think about What We Think about When We Think about Football (philosopher Simon Critchley) and What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (Murakami), and then I wonder about this turn of phase, and did it originate with Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love?

3. I discovered something about sparrows I did not know (and which will forever change my perception of them — in a good way!)

4. There is music. The whales that sing. The repeating lines “I thought”, “I wondered”, “I dreamed”, “I read” (but mostly “I thought”) tap out a steady and compelling beat.

5. Do read the Notes. They are fascinating.

6. Jan Morris, Olivia Laing, Ludwig Wittgenstein, social media, Carlo Rovelli, Virginia Woolf, Oliver Sacks, and more…

7. Pedal car.

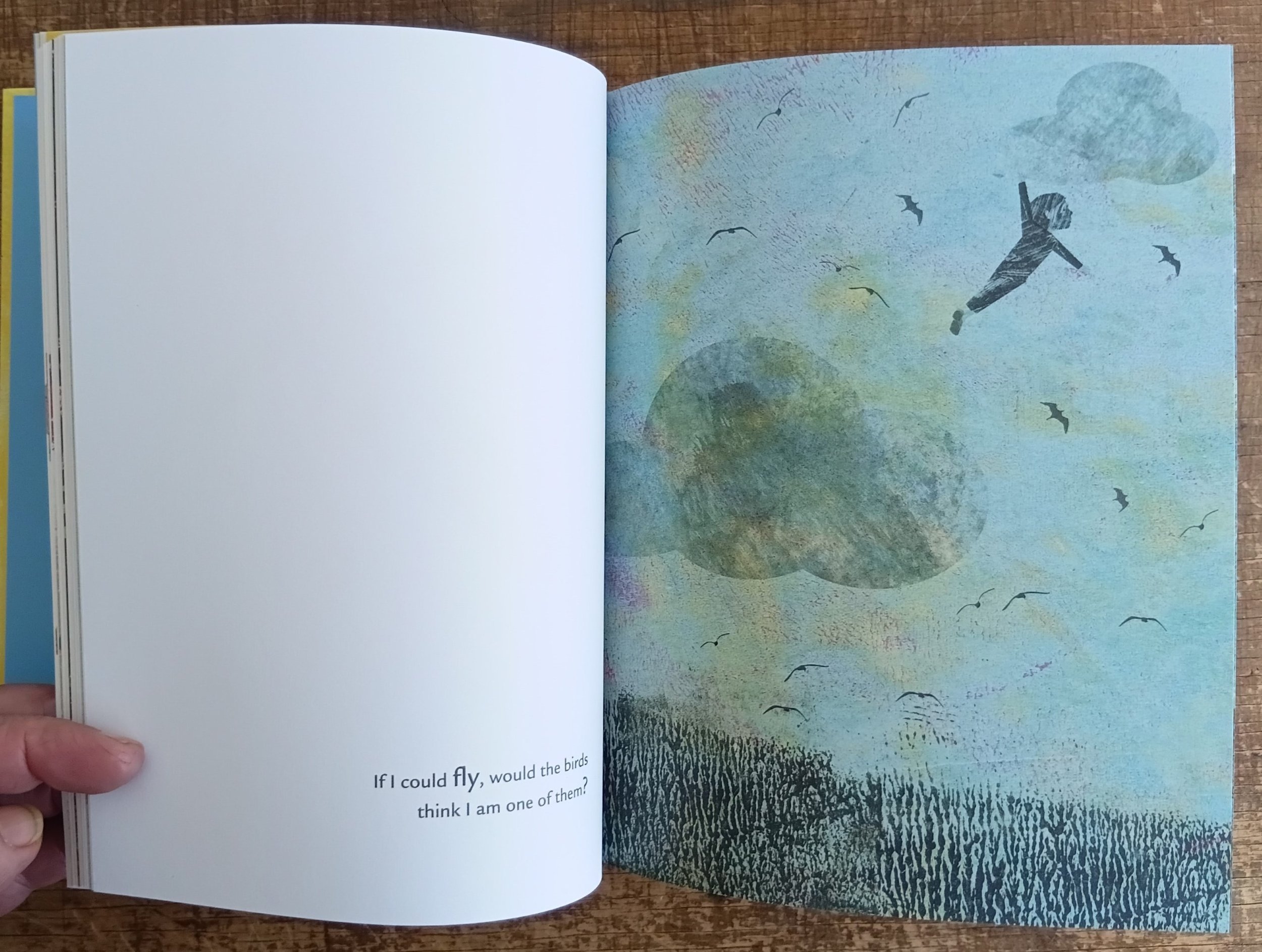

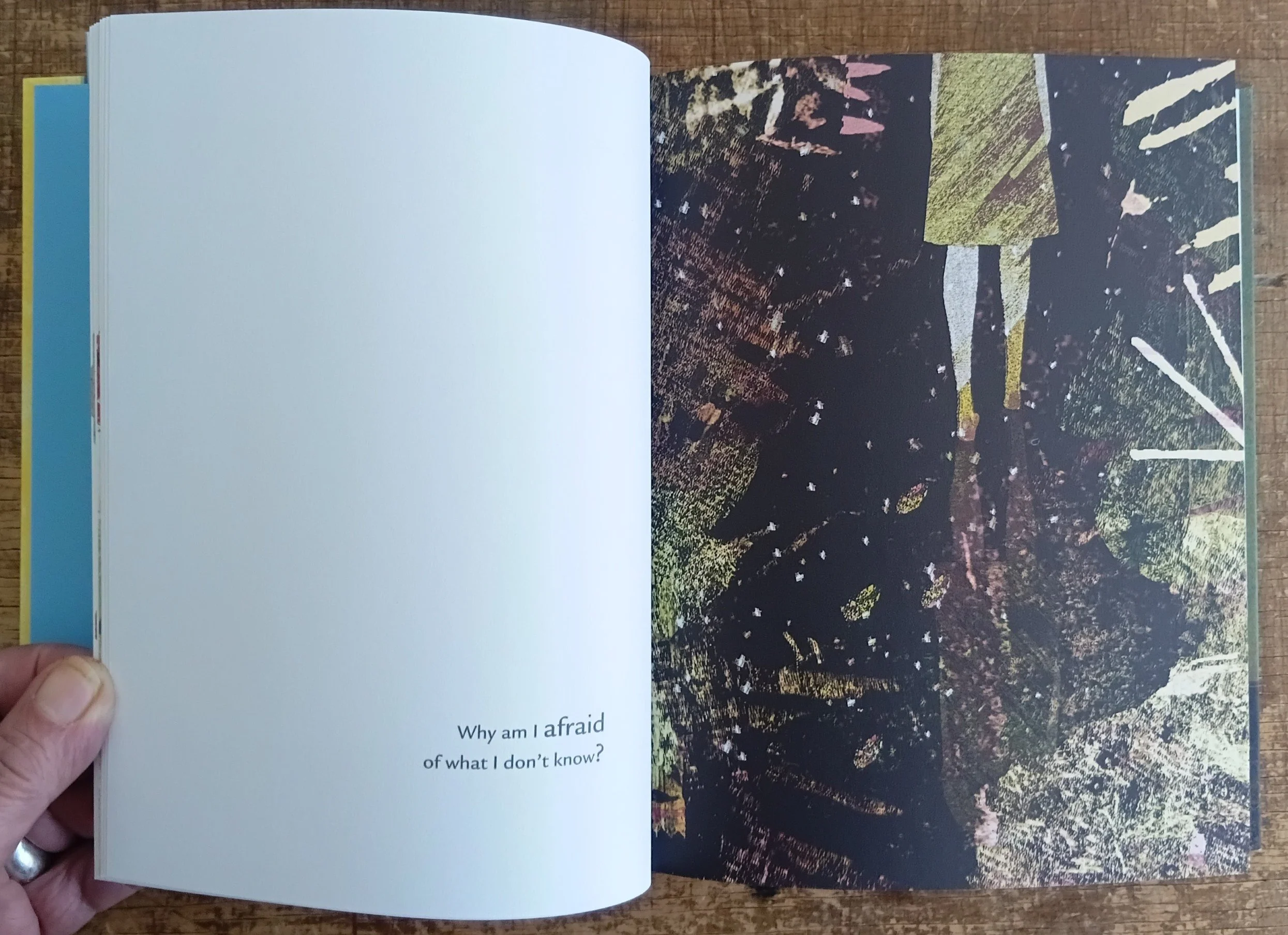

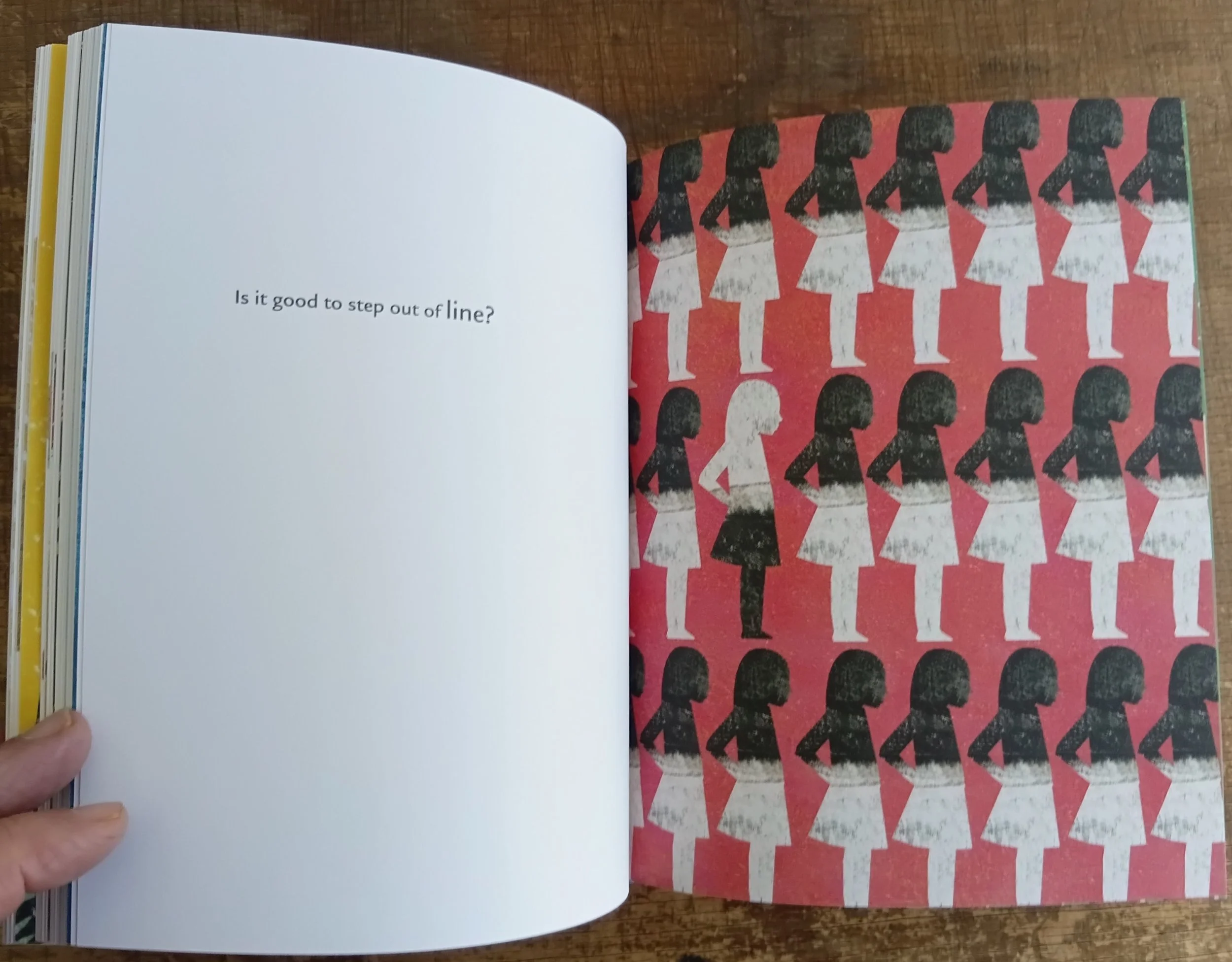

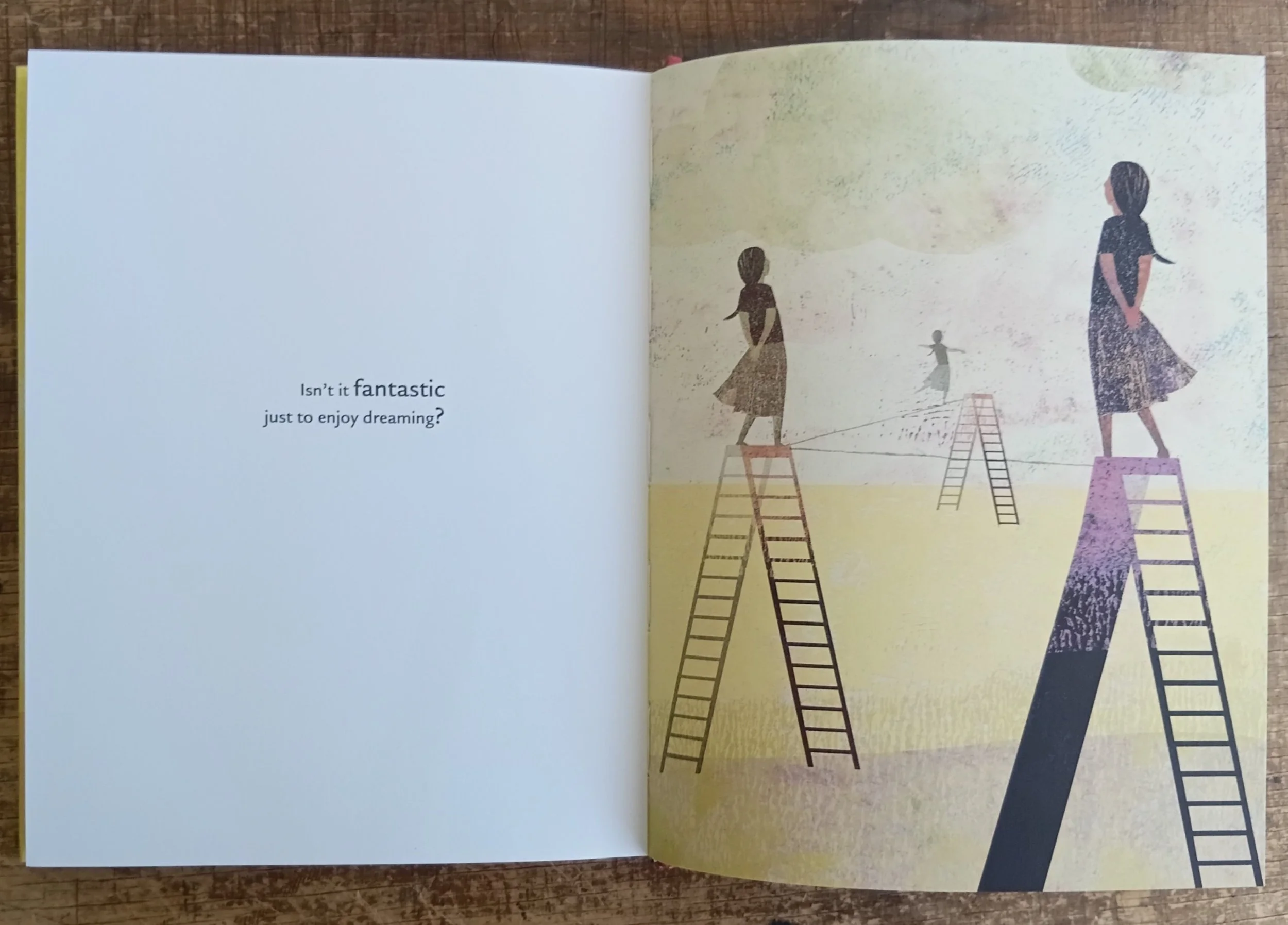

Britta Teckentrup is a German illustrator and author with over 70 children’s books to her name. Published in over 20 countries, she illustrates her own as well as other authors’ picture books. Many of her books quickly become favourites, and they range from board books to sophisticated picture books. What they all have in common is a desire to instill a feeling of wonder and curiosity. My favourite of her books is My Little Book of Big Questions. This is packed with ideas, beautifully illustrated, and filled with questions, both familiar and surprising. At 190 pages this is a substantial small hardback. The questions suit any age — from youngsters to adults. The ideas within these pages can be set free to roam in the imagination or used as conversation starters or prompts for writing or other creative responses. The questions range from the whimsical and tentative to the philosophical and provocative. Some questions may have answers and every reader will respond in their own way; other questions lead to more questions, opening doors to stories and journeys; while others will illicit a response of ‘who knows?’ Some questions trigger emotions, while other may send you on a fact-finding mission.

Here’s a small selection:

Will I be able to fly someday?

Who will be my friend?

Why I am afraid of what I don’t know?

Am I special?

Why is nature so colourful?

Are dreams as true as reality?

The illustrations, eye-catching and attractive, are variously thoughtful, joyful and enigmatic. Teckentrup uses colour, texture, silhouettes, and line to capture mood and emotion. There is joy in the light sky of a cartwheeling child. There is the brilliant blue of a dive into a pool of water. Rich textures adorn a field where a quest to find something hidden is under way. The bright yellow light of the future in seen through a window frame as a child looks from the familiar to the promise of what is to come. There is simpliicity of line and colour for quiet thoughts, and bold colours and energetic forms for questions that spur us to action.

This is a delightful book, one that I never tire of opening. It is brimming with ideas, both big and small, about feelings, human interactions, the meaning and the mysteries of life, and how all these things spark our imagination and keep us curious.

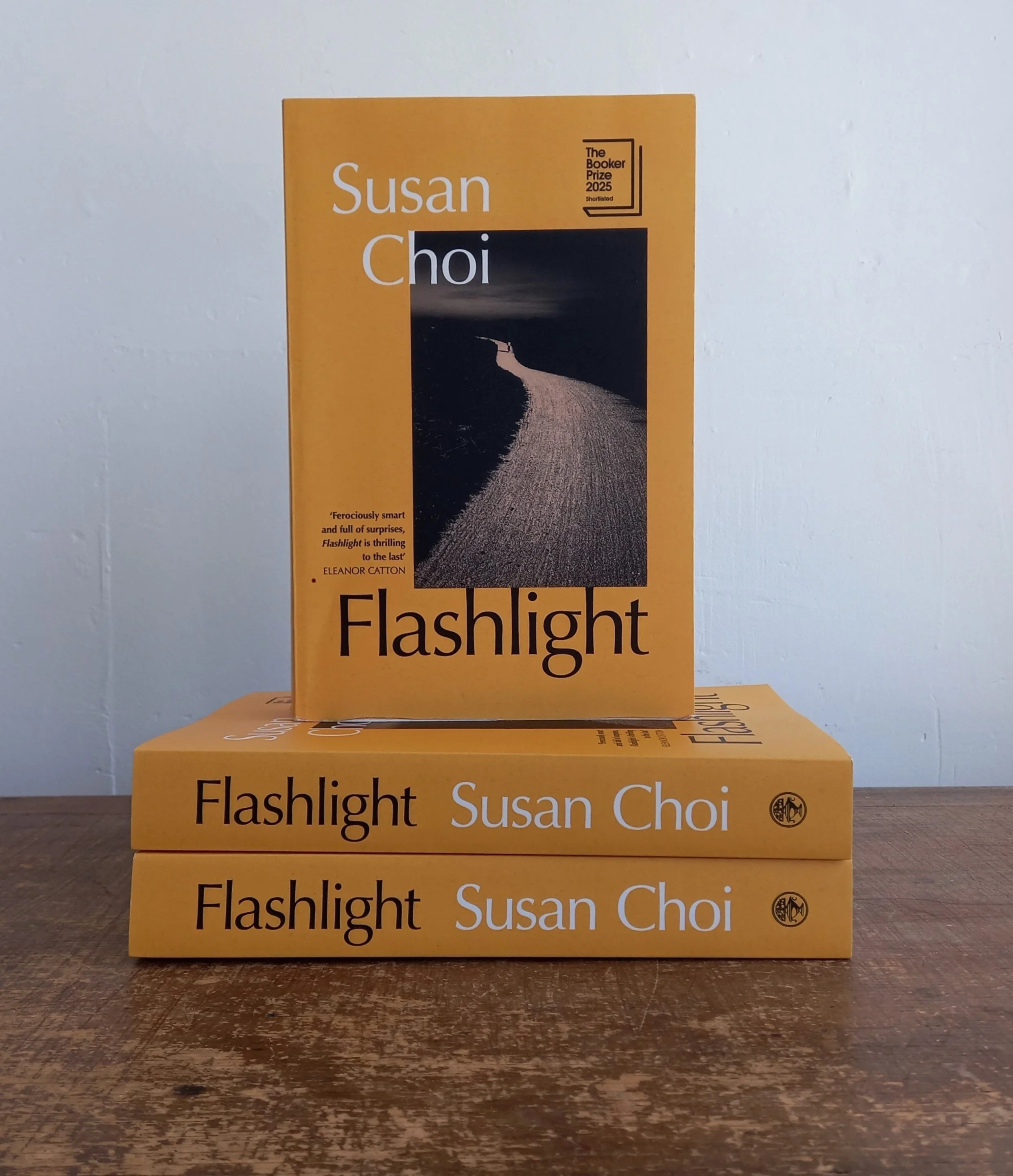

A night walking on the beach with her father Serk, looking at the stars, turns to tragedy for 10-year-old Louisa. Her father disappears, and is presumed drowned. She survives the tumult of the sea and is washed up on the shore, blue with cold, but in one piece aside from her memory of the evening’s events. Her last being the beam of the flashlight in her father’s hand, the light not revealing enough for a coherent story of what happened. Louisa and her parents have been living in Japan for the year. Louisa, although a conspicuously tall American-Korean child, had fitted in at school and her new neighbourhood. Unlike her mother, Anne, who struggled with the language, a husband who ignored her, and the onset of a degenerative disease. Serk and Anne had been at an impasse for a while, their relationship fraught and mechanical, sometimes violent. Each alone in their secrets and discontent. The distance and secrets continued to grow. Anne has made contact with Tobias, her son she had at nineteen, and doesn’t tell Serk. Serk is seeking his family, who left Japan to be repatriated to Korea, not to the island they were from, but to North Korea on the promise of a better life. A decision that Serk strongly disagreed with. In Flashlight, Choi swings the beam of the light from one to the other, taking us into the worlds and stories of each character. We head to the past. Serk’s childhood, where he is known as Hiroshi at school, and Seok by his family. (His name changes depending on his circumstances, Americanised, nickname, erased.) Here is the child that refuses to return to Korea, who thinks of himself as Japanese, but as a young man becomes embittered by his position in that society, and when an opportunity to leave comes, America beckons. Study and later a middling academic job. And a wife, and a child. We meet Anne, a girl mostly ignored, wanting something more than what is expected of her. Anne falls pregnant and her child is taken from her by the man she thought would save her from a dull life. Despite this deep sadness, she makes her way and is fiercely independent. Her marriage to Serk is another adventure, but one that after the first blush holds very little joy for her (or Serk) but they have Louisa. Louisa is cherished by both, but also caught in the crosshairs. She has Serk’s intelligence and Anne’s stubbornness. A fiery, as well as guilt-laden, relationship exists between mother and child; a tension that never resolves. Flashlight is a study in trauma, family dynamics, and in self. It’s outward and external in its telling of a piece of history of which I was oblivious (no spoilers here) and in relating the dynamics of this family unit with each other and in the world over several decades. It’s inward and internal in exploring the suffering, resilience, and resolve experienced by each of the main characters. There aren’t exactly happy endings here, but there is a sense of completion, which a less able novelist would have struggled with. This is a big novel — Flashlight is a novel that has much packed into it. Complex characters, with weaknesses and strengths; intriguing history which puts a spotlight on political power and nation-states; family relationships and secrets that hold no easy answers; and sharp writing that pulls it all together.

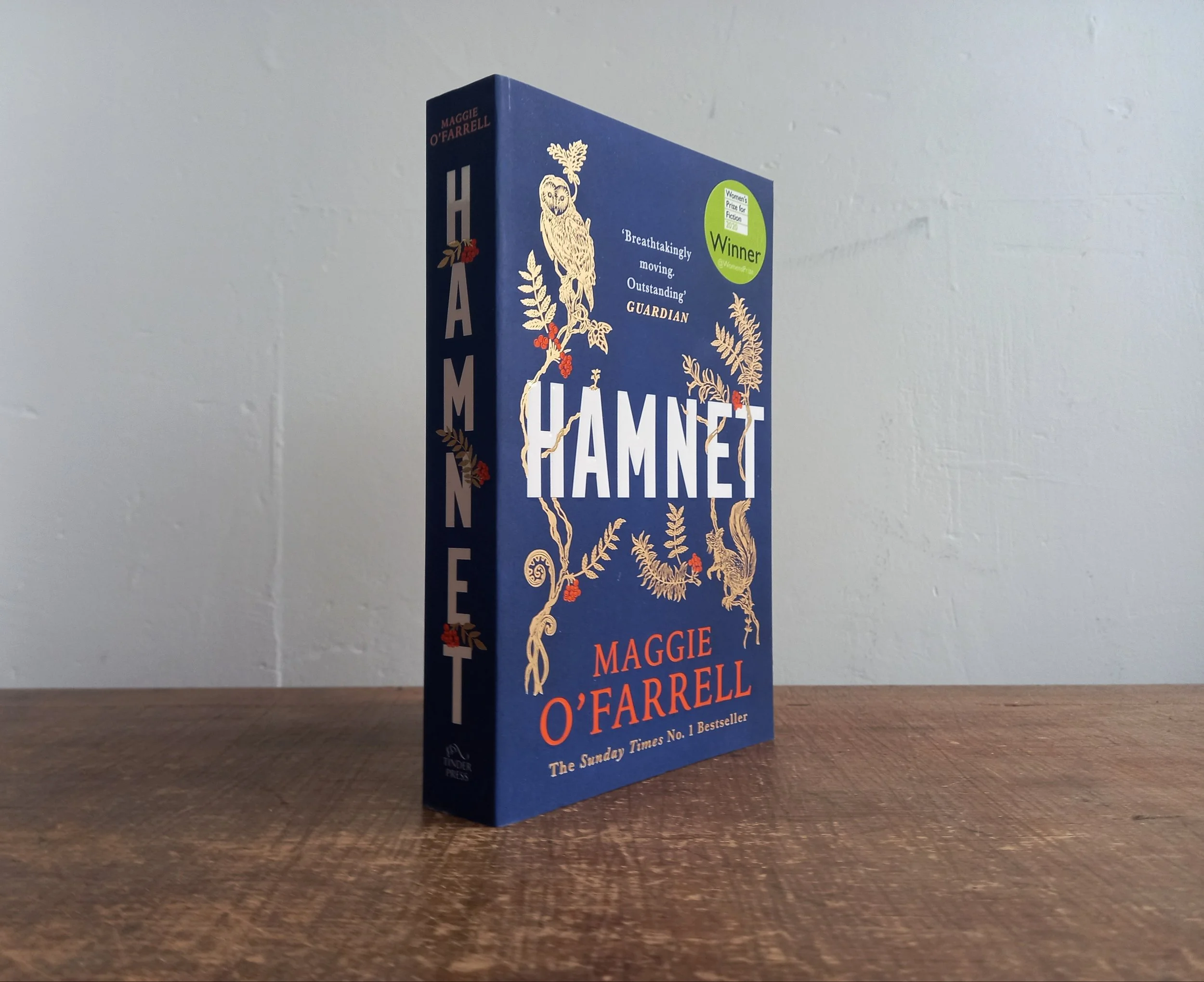

This evocative, heart-breaking, and revealing story of grief lays bare the genesis of Shakespeare’s most famous play, Hamlet. Yet in Maggie O’Farrell’s novel, Hamnet, Shakespeare as we know him hardly has a role. Set almost exclusively in the village of Stratford-upon-Avon and centred around the domestic life of his wife and family, Will is referred to as the Latin tutor, the glover’s son, the father, the husband. and is often working away — letters arriving at intervals. Who do we meet on the first pages, but the son — desperately searching for an adult to help him. His sister is unwell and the plague is present. From here, as time and the shadow of death make their presence known, we circle back increment by increment into the world of this child and his sister, of the mother, of the extended family and the village. We circle further back to the young Latin tutor gazing out the window, bored by the tedium of his job with boys who will never become any great things, and spying a youth (at first he mistakes his future wife for a lad) with a bird (later we meet this kestrel) upon her arm; and circle back again to the reasons why he is entrenched in this wearisome role — his violent and domineering father. Agnes is central and crucial in this novel. O’Farrell takes what little knowledge of Shakespeare's wife and brings her to the reader as a full and fascinating woman in her own right. She reels from the pages with her supposed eccentricities — she is a gifted healer, a lover of plants and the wilderness (seen by some in the community as a wild thing — a woman shunned by some but needed by others) — and her independent life. Emotional and emotive, sly and quiet, when death visits at her door, her grief is unbounded. Life has been snatched from her in a startling and, to her, an uncomprehending way. Agnes and Hamnet hold you in the grooves of this novel, make you want more, and they will stay with you long after the covers are closed. You reside within Hamnet’s mind as he navigates his twin sister’s illness, as he tries to find sense in the madness of the fever and the adult world that stands just outside his grip. You walk alongside Agnes as she loses herself in nature’s wildness to emerge into a world that can only tear at her, yet is necessary for survival and the memories that bind her child to her. Each character offers up a story — a way of seeing this world and telling its tale — a tragedy wrapped in intrigue on a small stage with rippling emotions. Hamnet is historical fiction at its best — in the vain of Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell series — it sets you fair and square in this time with all its life, death and drama. Immersive, compelling and rich in language and tale.

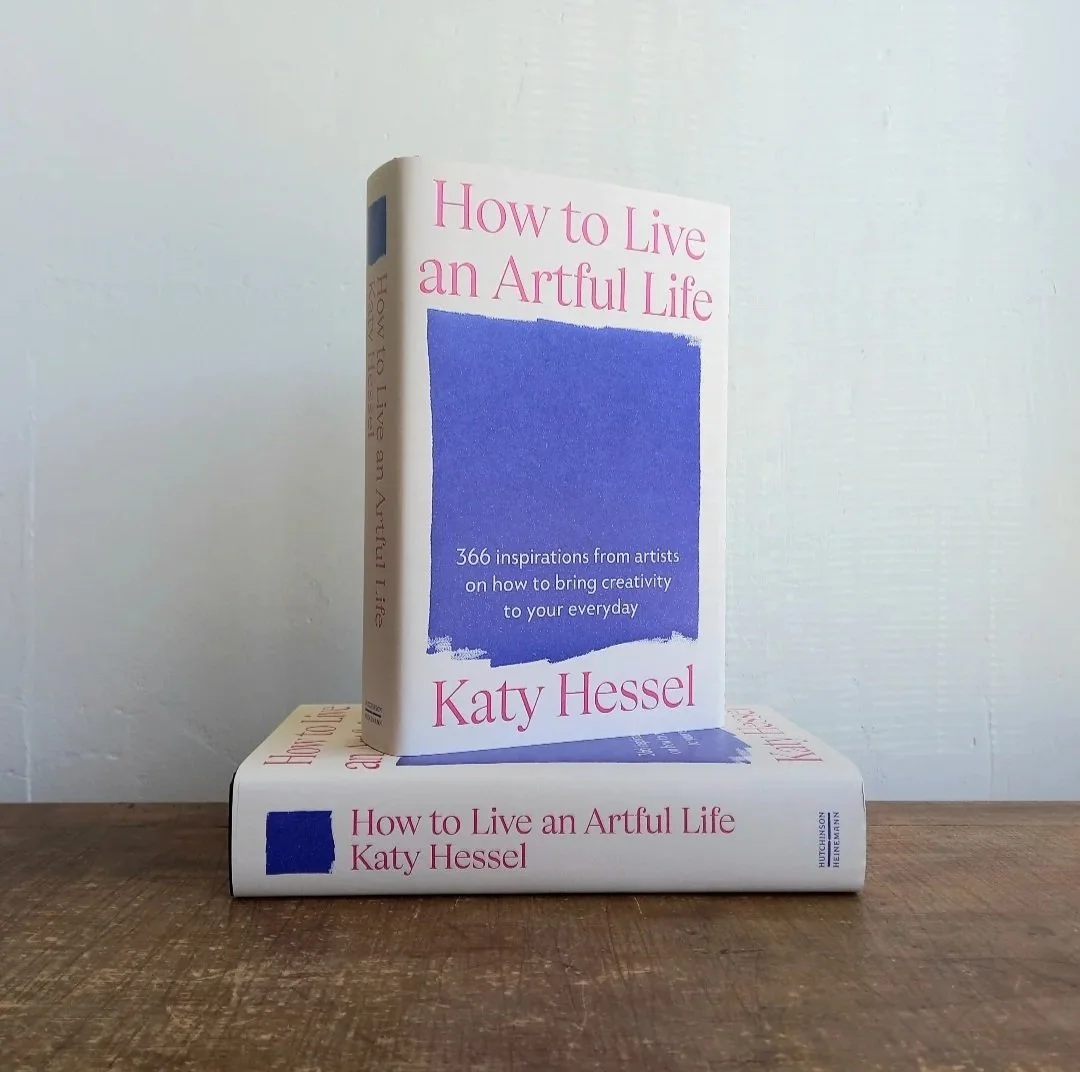

I’m usually suspicious of self-help books, inspiration-filled pages, and daily quotes, but when Katy Hessel’s book How to Live an Artful Life arrived, I was taken with it immediately. This may have been due my prior knowledge of her podcast, ‘The Great Women Artists’, or her art history book, The Story of Art Without Men, or because dipping in, I was intrigued by the breadth of the ideas, the quotes on creativity from both artists and writers, and the amount of information packed into each daily entry, and yes, inspiration. If you’re like me, and your art practice, although being an integral part of your psyche, is in practical terms an outlier crowded out by juggling two jobs, helping to keep the wheels turning at home, looking out for and spending time with your family, and the myriad of tasks that demand attention, then this is just the thing to enable a short window of focus. And this works for artists, writers, anyone that wishes to tune in to art (‘the artful life’) or learn to be more observant; to take the time. I’ll be using this book over the year ahead —366 entries, (but you can dip in and out wherever and whenever you like), so I’ve just read today’s entry. January 16: ‘Keep Looking’. It has a quote from writer Ruth Ozeki about spending time studying something intently — seeing more as you spend more time with an image or an object. This entry has a exercise to do. Some of the entries do — not all — but they are not compulsory, and by no means necessary, as the reading and your thinking will take you places. I’ve started a journal (I’ve always kept a visual diary (since being an art student), and occasionally blogged or had a journal on the go, but these have been erratic rather than systematic efforts) to go alongside the daily entries, jotting down my reactions to the passages and noteing ideas to come back to. (I’ve got 15 full pages already, so plenty of thoughts to record and ideas sparking!). The quotes from artists and writers are drawn from Hessel’s interviews or research, and it’s great to meet some new artists, as well as ones you know. So far, I’ve encountered Ali Smith, Ana Mendieta, Zoe Leonard, Louise Bourgeois, Tacita Dean, Deborah Levy, Kiki Smith, Anni Albers, plus 8 more. One a day. Their thoughts on creativity, Hessel’s commentary and things to think about or do, as well as information about the day’s artist or writer all packed into one succinct page or even half page. For the time-poor this is wonderful, as even on a busy day you can ensure at least keeping abreast of your reading, building a daily habit of engaging with and building your artful life. What I have found the most rewarding so far is remembering an artwork I hadn’t thought about in a long time, and the experience of interfacing with that work; looking at an object which I was very familiar with and finding something new in it; discovering some new artists and being reminded about ones that had slipped out of my consciousness; being more observant and remembering to push pause on the ongoing static of everyday menial tasks and open a window for a fresh portion of art. How to Live an Artful Life is both reassuring and challenging. Reassuring in the sense that your artful life hasn’t disappeared, it’s just a little overwhelmed by other demands and distractions; and challenging because you do find yourself stopping, questioning and focusing your mind on different ways to think about your relationship with art. Highly recommended.

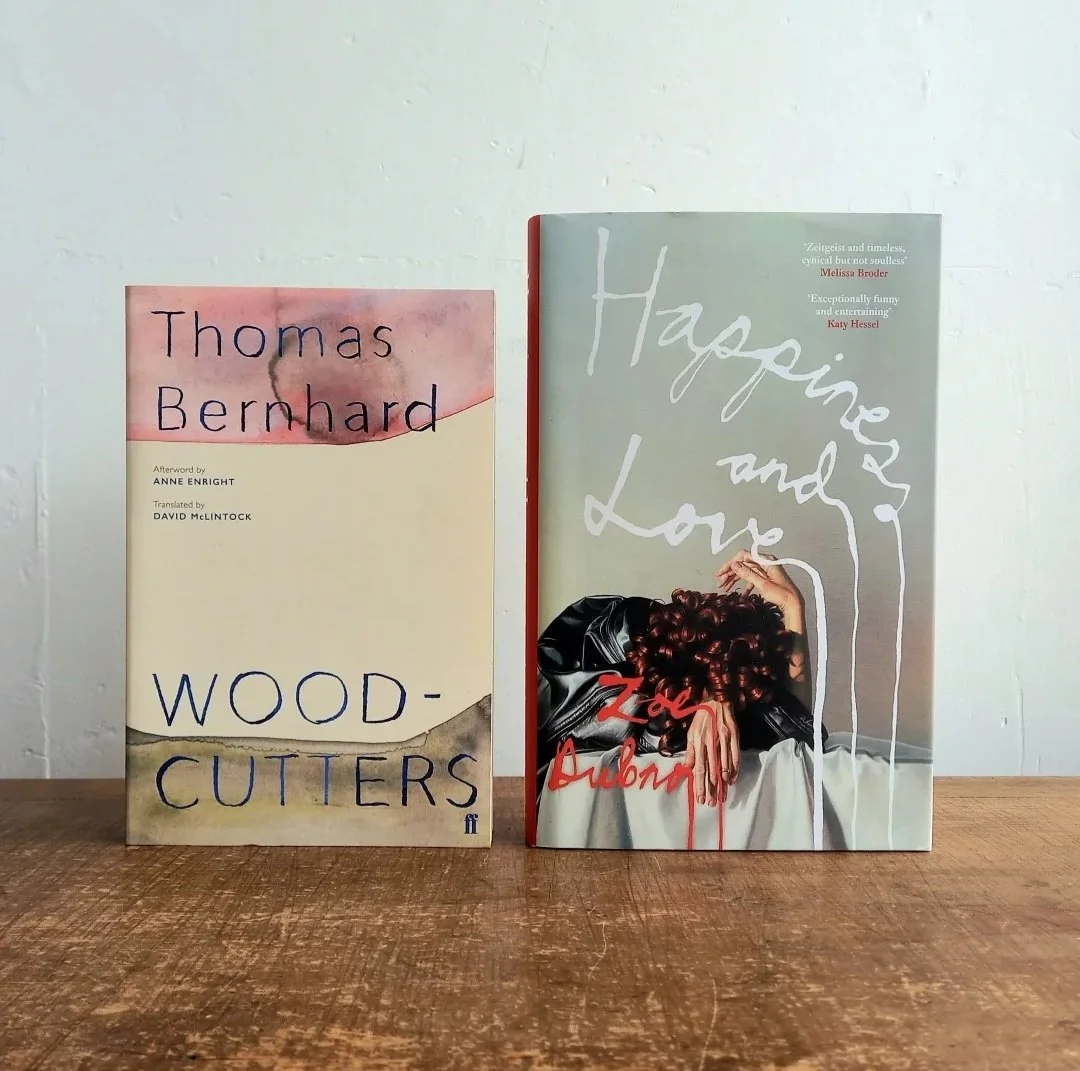

Ever found yourself at a dinner party you would rather avoid? Zoe Dubno tackles art and the creative scene, New York-style, in this sharp, slightly nasty, often wickedly funny novel. Our narrator, after escaping the claustrophobia of an art-scene couple who love to collect young artists and writers, finds herself smack back in the centre of their world again after the overdose death of Rebecca, a highly strung actress and friend. Inside the head of our narrator, we view the scene from her position seated on the white sofa in the high-end designer city loft. Here, across the room from her is the couple: Eugene pouring himself another wine and pawing a young naive hopeful artist, and Nicole, now aging, but still projecting all that money, position, and confidence can bring, regal in her control of the room and the people in it. Here too, is The Writer, Alexander, for whom our narrator has a particularly nasty case of bile. The narrator, a writer of medium success and not a lot of confidence (hardly surprising considering the company she has kept) keeps us engaged with her wry asides, observant eye (especially in retrospect — she has escaped, although now is feeling a little trapped and somewhat contrite), and laugh-out-loud snarkiness. Yet you also, like her, are a little repulsed by the company. This tension is cleverly pulled at by Dubno — letting us see, making us laugh and curl our lip simultaneously. We observe, we have our narrator’s internal dialogue of disgust and also self-loathing to digest, as well as her shocking unguestlike behaviour — several times she can hardly contain herself, breaking into barking and inappropriate laughter. As you read on, her behaviour towards this circle of writers, artists, wannabes, and the maniapulative couple at its centre is fully warranted. Here they wait for the guest of honour, a famous actress, here they say shallow things about the recently deceased Rebecca, they pontificate on their art — hint at their successes and talk up their brilliance, they fish for compliments and make snide putdowns to put others in their place, while working the room to their best advantage. Art is mentioned as if it is a by-product, merely a name-dropping convenience of what they truely want: attention. And when the dinner is finally served, the actress in her place at the head of the table, with Eugene slobbering over her as he is increasingly wine-fuelled and drug-sniffed, and Nicole sagely nodding and smiling to everything she says until… a conversation that cuts to the heart of the pretension plays out. The actress launches into a heated debate with the arrogant and soon-to-be-cut-down Alexander. Revenge for the narrator is sweet, the actress acting as a vehicle for our narrator’s distaste of the company. Zubno openly takes Thomas Bernhard’s The Woodcutters and brings it to America in the current century, using the same form — one paragraph (not that I noticed until the end) and one evening — and despite the shallow characters creates something clever, ruthless, and reflective. (I’ll be reading the original to compare.)

Every summer Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä escaped to Klovharun, their island. In Notes From an Island, Jansson gathers memories, notes, snippets of writing about the place and their antics on this barren remote skerry, and Pietilä’s atmospheric illustrations contrast with the seaman Brunström’s no-nonsense diary entries. This is a lovely book, from its attractive cover which features a delightfully drawn map by Jansson’s mother, to the paper stock and layout. It’s enticing in all its tactile qualities as well as its content. Jansson had been heading to the Finnish archipelago most of her life with her family. They would year-on-year visit a small island with charming beaches and a small wood, but each year the number of guests increased as they invited more friends and family to share in this summer pleasure. In her late 40s, Tove craved an island of her own. Somewhere she and Tuulikki could be alone to focus on their creative work, away from interruption and the pressures of life back on the mainland. Klovharun was rocky and inhospitable — just right for being away from it all, and for the two women an invigorating environment with the sea in all directions. Arriving on Klovharun they pitched a tent and, shortly after, met Brunström — a taciturn seaman — who would help them build the cabin. The initial step — finding a suitable flat space. A flat space that needed to be carved out by dynamiting a massive boulder. A dynamic action for a dynamic landscape. Yet Tove and Tuulikki liked their yellow tent so much that they continued to sleep in it and reserved the cabin for work and for guests. How do you claim an island in the Finnish Gulf? You place a notice on the door of a shop at the nearest local settlement stating your intention to lease the land and hope that most people will place a tick in the Yes column rather than the No. And hence a quarter-century relationship with the island began. In Jansson’s writing you get a sense of refuge, but not idle respite. Living on the island between April and October required stamina and industry — fishing, maintenance of the cabin and boat, keeping the various machines ticking over, collecting driftwood from the sea as well as the surrounding islands and rolling rocks. These were productive times — the women would work on their respective art and writing projects, and sometimes collaborate on a project. Pietilä recorded their experiences in this natural wilderness on Super8 film which was later made into a documentary. This book provides a thoughtful exploration of their island life and their relationship with nature. Tove Jansson’s writing is both philosophical and straightforward (it is never lyrical or florid). giving the land, the sea and the weather their primacy. Pietilä's 24 illustrations — some etchings, others watercolour washes — are muted in their ochre monochromes, but hold the power of the sky and water in them as though at any moment these elements might cast away the moment and shrug off these human interventions.

A conversation about hoarding, about collecting scraps of material and balls of wool, lead me to this delightful book. If you are a maker you will understand the problem of, and the desire for, a wardrobe just for fabric, wool, art supplies, and other ‘useful’ materials. You will also know the beauty of changing something from an remnant into an item — something that has a new lease of life, whether that is practical or simply to behold. If I could do one thing, and one thing only, it would be to make. Current sewing projects include recutting a vintage velvet dress (some rips, some bicycle chain grease) into a new dress, and, recently finished, a long-forgotten half-made blouse — fabric a bedsheet from the op shop. So I felt completely at home in Bound. And I devoured it with pleasure over one weekend. This is a book about a sewing journey, and a discovery journey. It’s about the end of things and the beginning of things. All those threads that tangle, yet also weave a story about who we are, where we come from and, even possibly, needle piercing the cloth, stitching a path to somewhere new. Maddie Ballard’s sewist diary follows her life through lockdown, through a relationship, from city to city, and from work to study, all puncutated with pattern pieces, scissors cutting and a trusty sewing machine. Each essay focuses on a garment she is making, from simple first steps — quick-unpick handy—to more complex adventures and later to considered items that incorporate her Chinese heritage. These essays capture the joys and frustrations of making, the dilemmas of responsible making (ethically and environmentally), the pleasure of repurposing and zero-waste sewing, and our relationship with clothes to make us feel good, to capture who we are, and conversely to obscure us. The essays are also a candid and thoughtful exploration of personal relationships and finding one’s place in the world. The comfort of one’s clothes and its metaphorical companion of being comfortable in one’s own skin brushing up sweetly here, like a velvet nap perfectly aligned. The book is dotted with sweet illustrations by Emma Dai’an Wright of Ballard’s sewing projects, reels of thread, and pesky clothes moths. The essays are cleverly double meaning in many cases. ‘Ease’ being a sewing term, but also in this essay’s case an easing into a new flat; ‘Soft’ the feel of merino, but also the lightness of moths’ wings; ‘Undoing’ the errors that happen in sewing and in life that need a remake. There’s ‘Cut One Pair’ and' ‘Cut One Self’. This gem of a book is published by a small press based in Birmingham, The Emma Press, focused on short prose works, poetry and children’s books. Bound: A Memoir of Making and Re-Making is thoughtful, charming and a complete delight. What seems light as silk brings us the hard selvedge of decisions, the needle prick of questions, and the threads that both fray and bind. Bravo Maddie Ballard and here’s to many more sewing and writing projects.

I entered The Rose Field with a mixture of trepidation and excitement. The long-awaited third instalment of ‘The Book of Dust’ trilogy has been much anticipated by fans of Lyra Belacqua and her daemon Pantalaimon. Six books and several novellas later, we finally are in Lyra’s world again, and at 600+pages the final book is quite a journey. We left Lyra in The Secret Commonwealth in a dangerous place without Pan, and intent on reaching the Red Building, on finding her daemon and her imagination. Lyra is now twenty, and in many ways takes a more measured approach to her journey, sometimes heeding the advice of her guide, but still the Lyra of Northern Lights remains — now more determined than headstrong. Yet the same questions prevail. Who can be trusted? Why are the Magisterium making alliances and gathering an army? What is the connection between Dust and the red building? And who wants to covet it and who wants to destroy it, and why? And where is Pan? As Lyra Silvertongue and Pantalaimon travel, one across land and sea, the other high into the mountains, we meet the gold-loving gryphons, the witches return, and Lyra has a strange encounter with an angel. Pullman draws us to characters both appealing and not, he creates situations where the intentions of some are unclear, and puts us inside the minds of some we would like to escape. Like Lyra, we are bound to move forward towards the questions that need stories, rather than answers. Along the way there are intriguing characters. The charming and powerful Mustafa Bey, a merchant who holds in his palm all the intricacies of connection and trade throughout the region. Malcolm Polstead returns — scholar, spy, artisan, and protector of Lyra. While there is no Serafina Pekkala, there are other witches as admirable, and there are the gold-loving gryphons. But best of all, and my favourite charcaters of The Rose Field, are Pan and Asta. The daemons are the heroes of this book. Yes, there is adventure, danger, crazed autocrats (Delamare is a fanatic), there is disorder in places and in people (Olivier Bonneville being the most damaged and possibly the most dangerous), there is the emotionally charged relationship between Lyra and Malcolm, and the possibility/impossibility of a future for them, and as always the question which will always remain, even at the conclusion, of the windows to the other worlds. What do they mean? Why they are feared by some, yet strike curiosity in others? And for others are portals that stoke their power and greed. As Lyra sees the world in all its destruction, can she also harness the good in it?

As with all high anticipated ‘finals’ there is commentary galore, and I avoided this until I closed the back cover. I was curious to find some disappointed — they wanted to come full circle back to the stories of a youthful Lyra. A sentimental journey which I was pleased was avoided. (In fact, there were unexpected twists, yet all in keeping with the essence of the series.) While others felt the conversations about consciousness and self were overplayed (strange — as this has always been a core aspect of the series, especially considering the relationship between a person and their daemon). Another theme that annoyed some was the focus on the environmental destruction due to greed and power. This again, is a core aspect of the whole series. In Northern Lights, what they were doing in the north, through either the desire for wealth or scientific discovery created a constant tension between the greater good and the short-term ill effects for some. I was pleased to see the concept of Dust still held that mysterious quality, now joined in memory with the highly sought-after rose oil, and the beauty of the roses although we only encounter this in myth. Curiosity remains, and like all good stories, there is no ending, and the possibilities for interpretation are endless.

Guestbbook is a project, as much as a book. My first Leanne Shapton experience was Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris — a novel about a relationship break-up in the form of an auction catalogue. Then Swimming Studies — a memoir of sorts with essays, photographs and illustrations (a new edition is on its way!) and also her collaborative work with Sheila Heti and Heidi Julavits, Women in Clothes, which is just brilliant and endlessly browseable. But I think Guestbook might top all these. It’s an experience, an art project, a rumination on memory and story-telling, with its collected images and texts and wonderfully strange, clever juxtapositions. These collected pieces are various and endlessly fascinating. In 'Eqalussuaq', a series of black-and-white photographs worthy of old nature magazines of the Greenland shark is captioned with snippets from newspaper items as well as a monologue of culinary requests to the possible chef for a private party sailing trip. 'At the Foot of the Bed', a series of photographs, some from magazine advertising, of empty beds have an eerie presence on the page — disturbing by their silence and strange wanting for someone or something to happen. There’s the story of a traumatised tennis player, Billy Byron, and his imaginary companion who drives him to the brink — a pinprick look at highly driven competitive personalities. It’s no coincidence that this book is subtitled Ghost Stories. There are ghostly apparitions, tales of odd happenings, old houses with haunting fables. Shapton is delving into and creating the unexplained, using memorabilia, found objects (photos and images), reminiscences, resonances and mis-tellings to make us look twice and then make us look again — think again. Her artworks from various projects are interspersed throughout, watercolours, drawings, sculptural and photographic work, and the overall black-and-white printing gives a feeling of timelessness or 'timetrappedness'. In 'The Iceberg as Viewed by Eyewitnesses', she matches drawings (falsely attributed to eyewitnesses of the Titanic sinking) with the incident book from an upmarket restaurant and bar — the complaints and how the staff dealt with the issues, alongside recommendations for more appropriate actions next time. Humour underscores many of the vignettes. What is true and what is real are not considerations in this Guestbook, but the emotions, the philosophical musings, and Shapton’s role as witness of events and medium of ghostly apparitions will delight anyone who likes to look sideways at the world with one eye squinting and a mind wide open to intrigue and play.

Forgotten in a trunk. Left in the dark. Unwanted. Once they had been on display, crafted with care. They belonged together and they had a story. Would they be together again, and would there be a new story? Kate DiCamillo works her magic with The Puppets of Spelhorst. With the texture of a folk tale, she reveals the story of a girl, a boy, a king, an owl, and a wolf. An old man sees a puppet in the window of a toy shop and the memory of a love is rekindled. He wants to take her home and look into her eyes so like those of his sweetheart long gone, but, bothersome: he has to have all the puppets. And so, it comes to be. In the night the girl sitting atop a dresser sees the moon and describes its beauty to her companions. The old man sleeps and does not awaken. And then an adventure begins. A journey that will take them through the hands of the rag-and-bone man, to an uncle with two inquisitive nieces, where a new story will be made — one which involves all of them; even though they will have their fierce teeth tampered with (the wolf), be mistaken for a feather duster (the owl), left abandoned outside and kidnapped by a giant bird (the boy), be snaffled into a pocket (the girl), and left alone with no one to rule (the king). Yet this is not the only story. Emma is writing, and Martha is making mischief. A story is ready to be told. An extra hand and a good singing voice are needed. In steps the maid, Jane Twiddum — someone who will have a profound impact on the fate of the five friends. The Puppets of Spelhorst is an absolute delight with its clever story. A spellbound tale. "Now it all happens," whispered the boy. "Now the story begins."

This the first of three fairy tales set in the magical land of Norendy. The second is equally charming, The Hotel Balzaar, and coming soon: Lost Evangeline.

This psychologically charged novel is a slow burn. Haushofer hypnotises us with the banality of suburbia — housework is a not only a constant occupation for our narrator, but also described in detail — and then awakens us to the trauma, both personal and societal, underpinning a week in the life of a middle-aged woman in 1960s Austria. On Sunday, she argues with Hubert, her husband, about the tree outside their bedroom window, an argument on repeat. He insists it is an acacia — she says an aspen, but maybe an elm. Their middle-age married life is one of habit and company, but also they appear estranged. Into this predictable existence, a disturbance from the past intrudes. A diary: its pages arriving in the mail over the week unsettle the woman. It’s her diary, an account of living away from civilisation, away from her husband, and small child, about twenty years ago. Who is sending them to her we never know, but she has her suspicions. Banished to the woods by her mother-in-law and by her husband to recover from a psychosomatic deafness as a young woman, her words on the page send her into a flurry of tasks — anything to avoid looking straight on. It is only in exhaustion that she has the courage to read, in private, in her loft, and then to take these pages to the cellar to burn. Both facing her past and expunging it. We are left in the dark, feeling our way, our ear attuned to a narrative not altogether reliable. A woman who, in spite of her fondness for Hubert, is trapped in a marriage and the expectations of being wife, mother, daughter. Here there is loneliness, repression and frustration. Her work as an illustrator has been stymied. Hubert admires her drawings and allows her time in the loft, but lacks understanding, relegating her art to a hobby. Like her two years in the woods, the loft symbolises both freedom ( à la ‘a room of one’s own) as well as threat. Here perfection does not come, she is restless and paces the floor. Is it the ‘mad woman in the attic’ or a woman recognising a truth? It’s the 1960s and the war still looms large. An amnesia has crept in, pushing against truth with attempts to relegate the war to acceptable stories, to move on and away from a collective guilt. The desire to forget, to repress the trauma at both a personal and societal level, drives the banality forward. The diary-entry arrivals in the letterbox disturb this illusion. Both threat and release, they insist on being recognised. For a book about trauma and seeking truth, The Loft is surprising wry. Haushofer’s final book is tautly written (well translated), strangely compelling, and a novel that comes into fuller focus when you step a little aside, as if the narrator has trained you to see the world as she does.

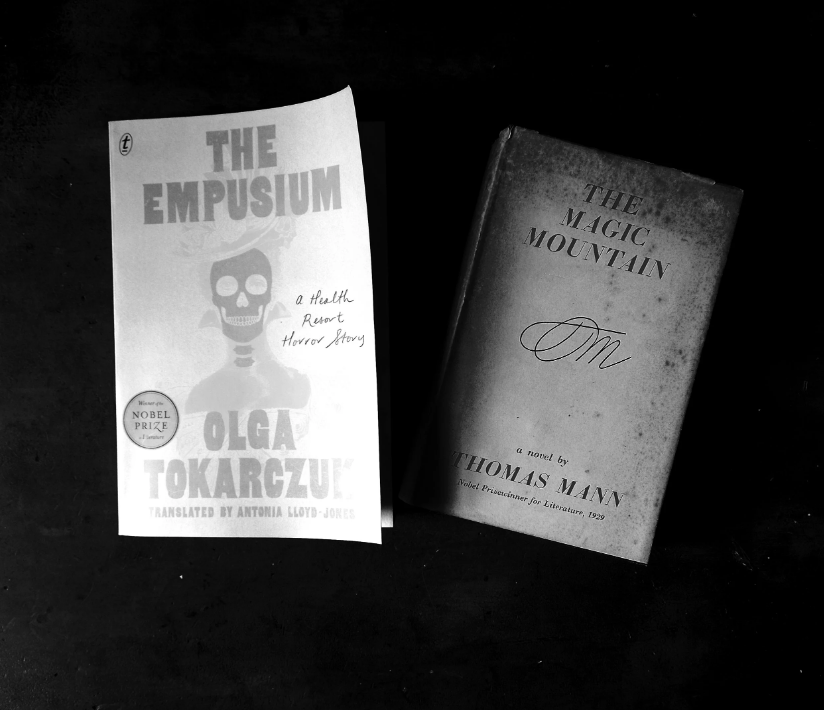

From the opening pages, its gothic lettering contents page, an image of a carriage arriving in a small mountain village surrounded by forests, the looming buildings of the sanatorium, you feel as if you have entered the opening scenes of Nosferatu. Olga Tokarczuk’s novel The Empusium, subtitled A Health Resort Horror Story, builds intrigue from the outset. It’s 1913, a year before great turmoil, and curing tuberculosis is all the rage. Our young Polish hero, Mieczyslaw Wojnicz, has been sent to the Silesian village of Gorbersdorf for the fresh air, the cold baths and the expert advice of Dr.Semperweiss. The sanatorium is popular and full. Wojnicz takes a room at the more economical Guesthouse for Gentlemen run by the unseemly Optiz with help of a rugged lad, Raimund. Here his fellow guests, after a day of health procedures and walks in the village, sit down to dinner together. It’s an evening of conversation, often arguments, about existence, human behaviour, psychology, and politics; as well as the purpose of women or more accurately their flawed views on the inferiority of women. This topic of conversation, much to the surprise and annoyance of Wojnicz, who they take pleasure in warning and teasing, is a frequent and recurring theme, helped along by a local specialty, a mushroom-infused liquor — the hallucinatory effects fueling the conversation, as well as driving the gentlemen towards introspection. Wojnicz’s fellow housemates include a serial returnee who seems driven by ennui, a humanist bent on lecturing our dear young hero, a young student of art (dying), and the aptly nicknamed The Lion, his bombastic nature making him easy to dislike. Thrown into this dysfunctional playground, the timid Wojnicz is unnerved, and this is not helped by a suicide by hanging on his first day in the house. A house with strange creakings, with cooing in the attic and the whoosh of that new thing, electricity. Not to mention the horror chair with straps in the room upstairs, the graves in the cemetery with an abundance of November death dates, and the uncanny behaviour of the charcoal burners in the forests. Secrets abound, and Wojnicz has several of his own he’s keeping close to his chest. Tokarczuk builds this multi-layered tale from snippets of Greek mythology, the new ideas of the period (think Freud) and as a response to Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (published 100 years ago). Like Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead there is a mystery here, a fizzing at the edges, black humour, and a deadly serious exploration of ideas. While Drive Your Plow is pushing the idea of eco-activist in response to harmful tradition, The Empusium is examining the misogyny of the 20th century canon and by extension the influence of these writers, philosophers and psychologists on the contemporary intellectual landscape. To counter the conversations of the ‘gentlemen’, there is a wonderful sense of being watched, that things are not what they seem, and justice will be done. In Greek mythology, the Empusai were shapeshifting creatures. Appearing as beautiful women they preyed on young men, and as beasts devoured them. Beware of those that have one leg of copper, and the other, a donkey’s. As Wojnicz finds the Guesthouse increasingly repressive, the rigours of treatment intrusive, the hallucinogenic effects of liquor to be avoided, and the tragic decline of the young man Thilo unbearable, he also finds in himself a strength as to date untapped. Whether from curiosity, delusion, avoidance of his own fraught familiar relationships, or an unconscious desire to live, our hero explores the depths of the house and the village in an attempt to discover what drives the men of this village to act so horrifically. Add into this rich psychological horror, rich, fetid descriptions of the forest, its minutiae, the fungi and foliage, an atmospheric mindscape grows. Reading The Empusium is like looking through a telescopic lens, one that fogs over, but a twitch of the controls, and a whisk of a cloth, brings it all into sharp relief. If you haven’t read Tokarczuk, it’s time to start.

If you can resist this book, you are an expert in avoiding something thrilling. Giselle Clarkson’s excellent book about all things birds is sure to engage young minds and old. Filled to the brim with intriguing information, it’s perfectly pitched with its bite-size chunks of text, excellent diagrams and illustrations, and humorous asides. Clarkson encourages us to be avian investigators: equipped with our toolkit of omnibird knowledge and our best tool — observation. Being a bird puzzle-solver has never been more lively. From poop to feathers, to all the parts of the wing, to the different styles of wings, and tails, and heads, and beaks, you’ll be spotting birds high above you, deciphering and coming up with —It’s a gull! A blackbird or possibly a thrush! A starling! There are 18 investigator notes featuring a range of birds, including ducks, gulls, corvids, chickens, flightless birds, birds of prey, and the humble sparrow. There are beautiful eggs (spot the odd one out!), a plumology lesson, an array of different nests from the carefully woven thrush work to the scattershot style of the sparrow, and an explainer on bird names — you’ll know your gymnorhina tibicen from your griseotyrannus aurantioatrocristatus in no time! And so much more. Clarkson’s wonderful illustrations draw you in (there’s great bird attitude here), and the text is lively — so many facts, but also humour and speculation. While there are answers to bird questions you didn’t know you had, there are also questions to ask. What does it feel like to fly? What are they saying? What bird would you be? There’s a charge to use your imagination and your detective skills (observational senses). It's a book about birds and it’s a book about noticing the natural world around us — its awesomeness. Omnibird is a gem — a book that informs, inspires and delights.

Ella loves horses. She loves her gran Grizzly and her home in a southern rural town. She’s most at home on her pony Magpie and cantering across the hills, especially at her favourite time of the day — the grimmelings — a time when magic can happen. Yet she’s lonely and wishes for a friend for the summer. Mum’s busy, and grumpy, looking after everyone and running the trekking business; Grizzly’s getting sicker, although she still has time to tell Ella and her little sister Fiona strange tales and wild stories of Scotland; and the locals think they are a bunch of witches. Ella knows there is power in words and when she curses the bully, Josh Underhill, little does she know she will be in a search party the next day. With Josh missing, and a strangely mesmerising black stallion appearing out of nowhere, this is not your average summer. When Ella meets a stranger, she strikes up an unexpected friendship. Has her wish come true? Why does she feel both attracted and wary of this overly confident boy, Gus? With Josh still missing, Mum’s made the lake out of bounds. That’s the last place Dad was seen six years ago. The lake with its strangely calm centre is enticing. What lurks in its depths — danger or the truth? Rachael King’s The Grimmelings is a gripping story of a girl growing up, of secrets unfolded, and a vengeful kelpie. Like her equally excellent previous children’s book, Red Rocks, King cleverly entwines the concerns of a young teen with an adventure story steeped in mythology. In Red Rocks, a selkie plays a central role, here it is the kelpie. King convincingly transports these myths to Aotearoa, in this case, the southern mountains, and in the former novel, the coast of Island Bay. There are nods to the power of language in the idea of curses, but more intriguing, and touching, are the scraps of paper from Grizzly with new words and meanings for Ella — and for us, the readers. Words are powerful and help us navigate our place in the world and ward off dangers when necessary. Yet the beauty of The Grimmelings lies in its adventure and in the courage of a girl and her horse, who together may withstand a powerful being, and maybe even break a curse. Laced with magical words, intriguing mythology, and plenty of horses, it’s a compelling, as well as emotional, ride.

Where can you fly through portals, confront monsters, make dragons your friends, adventure alongside amicable beasts, and be saved from danger by ingenuity, a little luck, and a good dose of knowledge? In books, of course. To celebrate the magnificent Taniwha landing, here’s a selection of books from our shelves.

Gavin Bishop’s books are always excellent. His new picture book, Taniwha, is a wonderful collection of pākūrau to expand your horizons, of creatures monstrous and tricky, as well as kaitiaki — protectors of people and the land and sea. Here you will find Tuhirangi who travelled with Kupe and lives in the depths of Te Moana a Raukawa, the tale of Moremore, son of Pania, who takes the shape of a shark, and the different natures of Whātaitai and Ngake — the taniwha of Te Whanganui o Tara. Beware the hunger of Tūtaeporoporo and the rage of Hotupuku. Superb illustrations, a glossary, and splendid story-telling.

If dragons are your game, look no further than Dragonkeeper by Carole Wilkinson. Set in the Han Dynasty, a slave girl finds out she is descended from a long line of dragonkeepers. Adventures ensue as Ping is set a great quest by an ancient dragon — a quest that will require bravery and heart. Along the way Ping will discover talents she possesses which will surprise not only her, but those she encounters on her journey.

(This is the first in an excellent series.)

Impossible Creatures: The Poisoned King is not to be missed nor triffled with. Head through the portal to a world of magical creatures, danger and intrigue. Well-paced action, humour, and emotional complexities make the nuanced writing of best-sellling author Katherine Rundell hard to put down. Open this book to a map of islands surrounded by mythical ceatures, and a warning!

“They would have said it wasn’t possible. They would have said she didn’t have it in her. It was in her, but deep. What’s under your house, if you were to dig? Mud and worms. Buried treasure. Skeletons. You don’t know. The girl dug into the depth of her heart and there she found a hunger for justice, and a thirst for revenge.”

Irresistible!

If you like graphic novels, Young Hag from the wonderful illustrator and writer Isabel Greenberg is a delight. It’s an alternative Britain of dragons and wizards, but the magic is fading. When a changeling is discovered in the woods, Young Hag, the youngest in her family of witches, is sent on a quest to discover the source of these magical problems. Greenberg ingeniously reinvents the women in Arthurian legend, transforming the tales of old into a heart-warming coming-of-age story.

A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin is now available as a graphic novel. Thoughtfully adapted by illustrator Fred Foreman, this will appeal to fans of the classic and those new to it.

Ged is on the path to being a mage, but to do so he must master his powers and confront a shadow-beast which he has let loose when toying with spells beyond his ability. Foreman captures the complexities of this coming-of-age story bringing the darkness and light of Le Guin’s story onto the page with a brooding colour palette, sweeping vistas, raw emotion, and visual details of the magical and natural world.

Meet Vera. She has lists. One list for Daddy and another for Anne Mom. Ten reasons each for staying together. Except one list only gets to 6. Vera is 10; she’s a brainiac — side-lined at school as ‘Facts Girl’ and trying to keep her ‘monkey brain’ in check. She’s Korean-American and half-Jewish with Russian grandparents. Vera, her little brother Dylan (cute, but mostly annoying), and her Daddy, Igor Shmulkin, and step-Mom Anne Bradford, a progressive blue-blood, live a modern comfortable life in an American city not too far in the future. Daddy’s trying to save a literary journal — hoping for the Rhodesian Billionaire to come through. Anne Mom is just trying to keep the household running smoothly while corralling her friends into good causes. As Daddy and Anne Mom descend into daily battles, Vera is having her own internal battles. Will she ever have a best friend? Will she find her birth mother, Mom Mom, before it’s too late? Is it safe on the streets anymore? America is in freefall, although for Vera at her good school, in her room of her own, in a safe neighbourhood, and with Kaspie (her AI device named after Gary Kasparov) at hand, it’s all at a distance. Until it’s not. Vera, or Faith is a very funny, but biting, satire. Observed through the eyes of a girl sideways to the world, Vera is the perfect vehicle for this look at a messed-up world, not that you will despair outright. You will be too busy laughing, liking Vera, and cheering her on. Fingers crossed that she wins the debate with her new-found friend, encouraging her to keep asking questions of her chess companion Kaspie (made in Korea), and to keep using that ‘monkey brain’ to solve the puzzle of Mom Mom. Yet the world will crash down, and ultimately Vera, who is a ten-year-old girl will find solace where she least expects it. So this is a sad, funny, good story with a rumbling darkness, a thunder clap of what is to come if we aren’t very careful.

A book about motherhood by Sheila Heti. Or is it? Heti’s ‘novel’, much like her excellent How Should A Person Be? is much less novel and more a series of not-quite-true but ever-so-true deliberations, and an existential rant — but the best kind: indulgent, prescient, intimate (unnervingly so at times) and extremely funny in a strange sideways glimpse at herself and others like her. Although she would almost believe she is the only one obsessing over the question, To have a child or not? It’s a book about motherhood, about being a parent, and what that relationship means or could provide a person, as much as it is a book about writing and the obsessive nature of creative practice and the need for this self-awareness to be a good creative — an 'art monster' (Jenny Offill, Dept. of Speculation). Yet Heti is torn between her desire to write and the pleasure, the satisfaction this brings her, and the confusion that swirls in her head about being a mother and whether this will bring her a different completion. As she obsesses about motherhood she questions everyone and observes her friends and family about this elusive — to her — state of being. She wrongly or rightly presumes that she should have a child, that she wants a child, and on the other hand, she does not. Her dilemma is mired in expectations, both external and internal, and the 'ticking clock', of which women are constantly reminded. Are you past the age of being a worthwhile contributor? Even in 2020, we are judged on our reproductive choices (think about women’s rights over their own bodies in regard to abortion laws), and somehow procreating, even in times of crisis (environmental and economic), is still way up there on people’s to-do lists. Not that Heti is overly concerned about the politics of reproduction or motherhood: her focus is on the intensely personal — on her experience and where these thoughts, these deliberations, take her and the reader. She’s irrational and highly emotional, and this makes her book one of the best about motherhood and the questioning of its function, on an intellectual as well as emotional level. Her book is, in the end, is as much a look at what it means to be someone's child as it is to have a child. Her deliberations take her on a journey of understanding her own mother and her grandmother and their roles as parents and individuals — a revelation that we don’t clearly think about. We know how we are as a child of our parents, but when do we consider what that relationship means from the other view — who we are, what we mean, to the mother (or father)? And if you can’t address your existential question about whether to have a child or not, you can do what Shelia Heti does and consult the coin — heads for yes, tails for no — and ask yourself a series of questions (often ridiculous and very amusing) about yourself, your intimates and your writing.

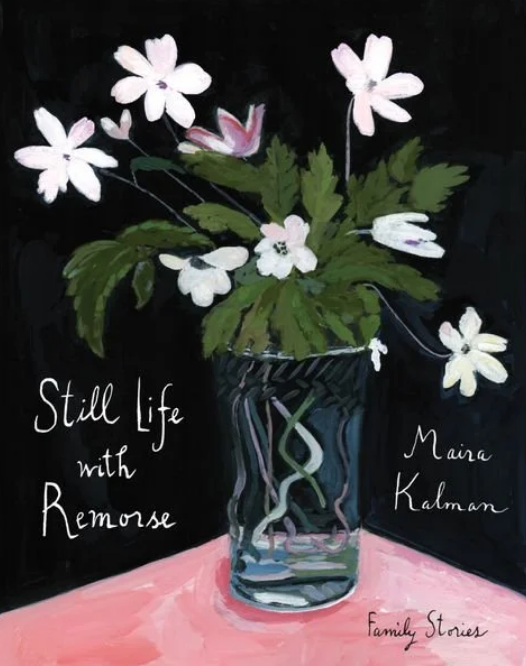

If you haven’t come across Maira Kalman’s work, you’re in for a treat. These seemingly ‘nice’ paintings are loaded with meanings, and double meanings, with irreverence and wit. They can also be morose or mundane, profound and sorrowful; Kalman’s wry humour keeping the darkest emotions at bay. They capture the full gamut of human life and interactions. And within all these complex emotions that Kalman’s picture and text publications provoke, there is a remarkable lightness which is exhilarating, making her books the ones you want to keep close. In Still Life With Remorse: Family Stories Kalman unpicks her own and other family histories. Here are the famous, mercilessly poked at. The Tolstoys’ disfunction, Chekov’s misery; Kafka and Mahler both bilious, driven by regret (and family) to create; and here is Cicero, regretting everything. But these are mere interludes, along with the musical intervals, to the stories at the heart of this collection of writings and paintings. Here are the empty chairs, the tablecloths, the people gathered, the hallway, the death bed, the flowers in vases and the fruit in bowls, all triggering a memory, all resting not so quietly. Here are the parents, the uncle, the sister. Here is the aging, the forgetting and the not forgiving. Stepping back to the Holocaust, to Jaffa, to those who left and to those who were erased. Here are the choices and the impossible sitting-around-the-room, still living. Walking through one door and into another place, remorse following. Despite it all, there is a way to step out of one’s shoes and walk free. Still Life With Remorse is, in spite of itself, life, that is, merriment.