NEW RELEASES

Mary's Boy, Jean-Jacques; And other stories by Vincent O'Sullivan $35

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly {Reviewed by STELLA} Greta and Valdin are siblings. They live together in central Auckland. Greta is working on her Master’s thesis in comparative literature, enamoured with fellow student Holly and navigating her queerness and her mixed cultural heritage. Valdin has thrown in his career in astrophysics at the University, and has found a new role as a TV presenter — something he is unexpectedly doing well at — and is pining for his ex-boyfriend, Xabi. Basically, he’s having a crisis. In Rebecca K Reilly’s assured debut novel the chapters move between the narratives of these two siblings, their voices distinct and compelling, as they live and love in Tāmaki Makaurau. The city itself, richly described and lively, is a character in itself. While some readers will fall into this novel with little effort — the dialogue and character interactions relatable and the cultural references (films, music and memes) relevant — others will ease in more slowly as they walk along with these 20-somethings in contemporary Aotearoa. For this is a story at first glance about being young, about finding your way and being in love. It has those Sally Rooney hooks. But Reilly has more going on here and you can take this as a sharp, funny and romantic escape or dig a little deeper. The Vladisavljevic family is a blend of Maori, Russian and Catalan, which makes for some great family conversations and interesting experiences for the characters. Here, Reilly, uses humour as well as anger to put the spotlight on racism and prejudice. From the outburst of Valdin on location in Queenstown to the more subtle undercurrents in Betty’s life, from Greta’s annoyance at being pigeonholed to Ell’s exclusion from her family. As we get a glimpse into the lives of other family members, Greta & Valdin becomes a richer novel — more assertive and nuanced. What is family? Why and how does circumstance dictate choices made, paths taken. And how can love be exhilarating, sad and wonderful simultaneously? Whether it is Reilly’s intention or not, Greta & Valdin sings from a similar song sheet as a Dickensian family saga or a Jane Austin classic. The novel opens with despair and ends with a wedding, and is an emotional rollercoaster in-between. There are the complex family interchanges, the tales of woe and happiness, and machinations between characters that lead to both misunderstanding and revelation and acceptance, hurt and forgiveness, romantic and familial love, and humour — complete with witty dialogue. And all set in a distinctly vibrant contemporary Aotearoa complete with all its flaws and charm. And who can resist a happy ending? Shortlisted for the Acorn Prize 2022. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | ||

Mouthpieces by Eimear McBride {Reviewed by THOMAS}

|

>>Read an extract.

>>Have a look inside the book.

>>Ten questions.

>>Collaboration at the core.

>>Something about light.

>>James Hackshaw's public buildings.

>>An interview with the author.

>>The McCahon House.

>>Your copy.

>>Some books about Colin McCahon.

>>Some books about Paul Dibble.

>>The short lists for the 2022 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

NEW RELEASES

Word by word, inch by inch, Gigi Fenster immerses us in the increasingly unsettling psyche of her narrator. Olga lends a hand with her friend’s daughter, who has recently given birth, but the helpful old woman gradually takes on a more sinister role. It is an unnerving and absorbing reading experience as the darkness gradually closes in. Fenster creates an unforgettable voice, which at first seems so light and benign as — impeccably paced — the psychological tumult builds to a truly mesmerising crescendo.

Entanglement by Bryan Walpert (Mākaro Press)

Dazzlingly intelligent and ambitious in scope, Entanglement spans decades and continents, explores the essence of time and delves into topics as complex as quantum physics. But at the heart of Bryan Walpert’s novel is the human psyche and all its intricacies. A writer plagued by two tragedies in his past reflects on where it all went wrong, and his desperation leads him back to Baltimore in 1977. A novel unafraid to ask difficult questions, and a novelist unwilling to patronise his readers.

Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K. Reilly (Te Herenga Waka University Press)

From the very first page, this novel has readers laughing out loud at the daily trials of these two Māori-Russian-Catalonian siblings. The titular characters navigate Auckland while dealing with heartbreak, OCD, family secrets, the costs of living, Tinder, public transport and more, and they do it all with massive amounts of heart. Greta & Valdin is gloriously queer, hilarious and relatable. Rebecca K. Reilly's debut novel is a modern classic.

Kurangaituku by Whiti Hereaka (Huia Publishers)

Ten years ago, Whiti Hereaka decided to begin the task of rescuing Kurangaituku, the birdwoman ogress from the Māori myth, 'Hatupatu and the Bird-Woman'. In this extraordinary and richly imagined novel, Hereaka gives voice and form to Kurangaituku, allowing her to tell us not only her side of the story but also everything she knows about the newly made Māori world and after-life. Told in a way that embraces Māori oral traditions, Kurangaituku is poetic, intense, clever, and sexy as hell.

BOOKSELLERS AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND AWARD FOR ILLUSTRATED NON-FICTION

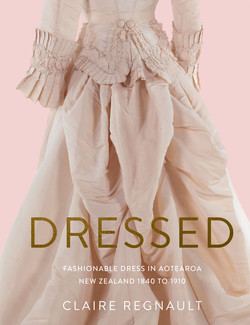

Dressed: Fashionable Dress in Aotearoa New Zealand, 1840 to 1910 by Claire Regnault (Te Papa Press)

This beautiful and beguiling book will seduce a wide audience with its stunning images and informative text, focusing on our ancestors’ lives through the lens of their clothing. Elegantly designed and sumptuously presented, it covers the diversity of sartorial experience in 19th Century Aotearoa as it addresses simple questions such as: Who made this garment? Who wore it, and when? A valuable addition to our nation’s story, it will have wide cultural and educational reach, and is an outstanding example of illustrated non-fiction publishing.

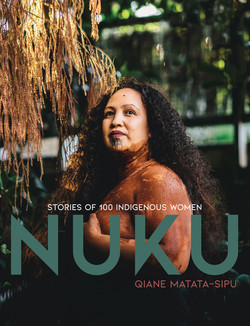

NUKU: Stories of 100 Indigenous Women by Qiane Matata-Sipu (QIANE+co)

The strikingly successful outcome of an ambitious project to showcase indigenous women going about their daily lives, doing both ordinary and extraordinary things. The 100 varied examples of talent and triumph are presented in a simple magazine-style format that is as accessible as it is effective. The author gracefully presents her subjects in their own words, stepping aside in the text but being wonderfully present through her tremendous portrait photography, which works seamlessly with the elegant, unpretentious typography in a beautifully cohesive package.

Shifting Grounds: Deep Histories of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland by Lucy Mackintosh (Bridget Williams Books)

A fresh and timely study that weaves multiple narratives across time and space into a highly readable story, revealing the deep histories and continuous remaking of selected landscapes across Tāmaki Makaurau. The clean presentation of both often startling historic images and contemporary photography, and the skilfully written text informed by serious scholarship, fill some of the gaps in the stories of Auckland. The inviting format and careful, uncluttered design will appeal to a wide audience. An impressive first book.

The Architect and the Artists: Hackshaw, McCahon, Dibble by Bridget Hackshaw (Massey University Press)

A thorough and beautifully produced triangulation of creative practice that shows the value of collaboration in the arts, as evidenced in the collective projects of James Hackshaw, Colin McCahon and Paul Dibble. Archival material (including personal correspondence and sketches), informative and reflective text, and powerfully evocative photography are delivered cohesively through clean and lively design and typography. The author’s clear labour of love is reinforced by excellent external contributions, making for an enlightening and brilliant whole. Another impressive and assured first book.

GENERAL NON-FICTION AWARD

From the Centre: A Writer’s Life by Patricia Grace (Penguin Random House)

On one level this is a personal memoir of love and of family — Patricia Grace writes of her husband, her children and her extended family, of being schooled and of teaching — but her life is also played out in the context of social history, the time when many Māori began to move from rural to urban environments; Grace is always aware that she lives within a much larger community. Hers is a rare literary memoir, free of egotism.

The Alarmist: Fifty Years Measuring Climate Change by Dave Lowe (Te Herenga Waka University Press)

In this wide-ranging autobiography, Dave Lowe follows New Zealand’s critical role in charting carbon emissions from the 1970s onwards. Writing of the methodical collection of critical data allows Lowe to convey major scientific concepts to the general reader in a very accessible way. The Alarmist has a rich texture of family and a clear awareness that members of the scientific community are not always in harmony. It is enlightening as well as very readable.

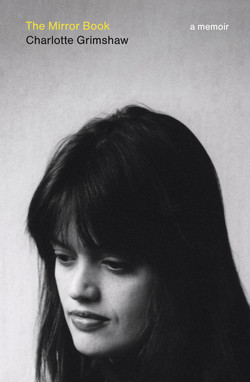

The Mirror Book by Charlotte Grimshaw (Penguin Random House)

A writer of novels and short fiction turns to non-fiction with a memoir par excellence. In this book of trauma, recovery and self-discovery, the prose is exquisitely precise in its navigation of the complexity of the author’s family dynamics and its interrogation of how it has shaped the construction of her identity and influenced her writing. The Mirror Book combines the personal and the literary with the sociological. It has been — and deserves to be — widely read.

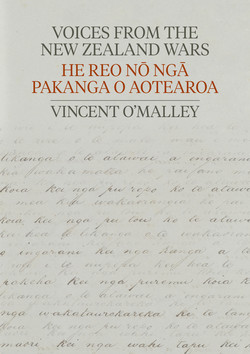

Voices from the New Zealand Wars | He Reo nō ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa by Vincent O’Malley (Bridget Williams Books)

An admirable work of historical scholarship drawing on many sources, Māori and Pākehā. Vincent O'Malley's craft lies in unpacking those sources in an eloquent and incisive way, and he helps readers to think critically as he presents balanced arguments about contested battles and other conflicts. In the process, he weaves a coherent history of the New Zealand Wars. Essential reading for New Zealanders, with the bonus of excellent book production by the publishers.

MARY AND PETER BIGGS AWARD FOR POETRY

Rangikura by Tayi Tibble (Te Herenga Waka University Press)

In Rangikura, Tayi Tibble further enhances her deserved reputation as a poet who writes with vibrant energy and talent. She has vision, and here sets out to combine vernacular with refined poetics, giving a voice to urban Māori. The result is dense and rich with life and language. These poems pay tribute to Millennial culture and use the power of humour, sexuality and friendship to create a collection that encapsulates this generation of Aotearoa.

Sleeping with Stones by Serie Barford (Anahera Press)

Through a kind of verse novel, Serie Barford builds the story of a person, a loss and a life that continues on despite it all. Sleeping with Stones is a skillfully structured collection in which each poem accumulates and moves through time. Barford’s gift is her ability to use simple eloquence to write about complex matters. This collection does what poetry should do: give words to the things for which there are no words.

The Sea Walks into a Wall by Anne Kennedy (Auckland University Press)

An up-to-the-minute contemporary collection that tests the very limits of what poetry can do. With her playful intellect and supreme confidence, Anne Kennedy creates poems that are consistently engaged with issues of the anthropocene, beneath which a constant, powerful tide flows and pulls. Worldly, and deeply in the world, The Sea Walks into a Wall bears witness to the grit and gravity of contemporary life.

Tumble by Joanna Preston (Otago University Press)

Each poem in Tumble is a glimpse into a different world, and no two poems inhabit the same reality. Drawing from lines of art, history, contemporary journalism and fellow poets, the collection confidently shifts perspectives and registers, points of view and tone, while being held together by Joanna Preston’s light touch. Her pristine imagery and fine ear for rhythm and beat means every poem — and the book itself — is a celebration of poetry.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

The Block by Ben Oliver {Reviewed by STELLA} You can run, you can hide, but eventually Happy will find you. Luka and his friends made it out of The Loop in book one of this trilogy to join an uprising — a revolution of the Regulars against the Alts and Galen Rye’s plans. Yet Luka’s freedom was short-lived and now he’s imprisoned again — you can’t always escape super soldiers no matter how determined you are — this time in The Block. If you thought The Loop was repressive, it’s a walk in the park compared with Luka Kane’s new residence. Hours paralysed on a bed, only to be awoken for energy harvesting and mind games are taking a toll on Luka’s sanity and his desire to find The Missing is a distant dream. So is the chance he’ll ever see his friends again, in particular Kina. Yet the unthinkable happens and he finds someone he can outwit — someone who empathises — just in time for a daring rescue. Although is this just another simulation from Happy? Is it real? Well, it turns out that it is, and once again Luka is in hiding and trying to find a way to avoid the wave of destruction that is bearing down on him, and those that don’t wish to be absorbed into the new world dictated to them by a corrupt, and possibly insane, entity. There are more daring explorations in the ruined city, a hiding place through a maze of underground tunnels, and a new plan to find The Missing while avoiding the increasing surveillance of Happy. Drones are everywhere (only one is a friend), as are Alt soldiers, and the AI, Happy, is up to something sinister at the Arc. Luka finds himself propelled into taking things into his own hands, even though it means he will need to abandon his friends again. To save them, he must go his own way and Tyco — his nemesis — has turned up again. stronger and more dangerous. Can Luka keep his promise to Kina? Can he find his sister, Molly, and what is the strange place called Purgatory? The second book in this trilogy is just as action-packed and fast-paced as The Loop, with plenty of emotional heft and some humour to temper the more gruesome moments and weighty themes. No surprise the second book ends on a cliffhanger! Roll on the third. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

Die, My Love by Ariana Harwicz (translated by Sarah Moses and Carolina Orloff) {Reviewed by THOMAS} If a thought is thought it must be thought through to its end. This formula is productive both of great misery and of great literature, but, for most people, either consequence is fairly easily avoided through a simple lack of tenacity or focus, or through fear. Unfortunately, we are not all so easily saved from ourselves by such shortcomings. The narrator of Ariana Harwicz’s razor-fine novel Die, My Love finds herself living in the French countryside with a husband and young child, incapable of feeling anything other than displaced in every aspect of her life, both trapped by and excluded from the circumstances that have come to define her. She both longs for and is revolted by family life with her husband and child, the violence of her ambivalences make her incapable of either accepting or changing a situation about which there is nothing ostensibly wrong, she withdraws into herself, and, as the gap separating herself from the rest of existence widens, her attempts to bridge it become both more desperate and more doomed, further widening the gap. Every detail of everything around her causes her pain and harms her ability to feel anything other than the opposite of the way she feels she should feel. This negative electrostatic charge, so to call it, builds and builds but she is unable to discharge it, to return her situation to ‘normal’, to relieve the torment. In some ways, the support and love of her husband make it harder to regain a grip on ‘reality’ — if her husband had been a monster, her battles could have been played out in their home rather than inside her (it is for this reason, perhaps, that people subconsciously choose partners who will justify the negative feelings towards which they are inclined). The narrator feels more affinity with animals than with humans, she behaves erratically or not at all, she becomes obsessed with a neighbour but the encounters with him that she describes, and the moments of self-obliterative release they provide, are, I would say, entirely fantasised. Between these fantasies and ‘objective reality’, however, falls a wide area about which we and she must remain uncertain whether her perceptions, understandings and reactions are accurate or appropriate. At times the narrator’s love for her child creates small oases of anxiety in her depression, but these become rarer. Harwicz’s writing is both sensitive and brutal, both lucid and claustrophobic, her observations both subtle and overwhelming. As the narrator loses her footing, the writer ensures that we are borne with her on through the novel, an experience not dissimilar to gathering speed downhill in a runaway pram*. *Not a spoiler. |

>>Read Stella's review.

>>Inside the mind of Thomas Mann.

>>At the Thomas Mann House.

>>What's the story?

>>"Stop this nonsense!"

>>"I grew up in a society where homosexuality was unmentioned."

>>Socks.

>>Shortlisted for the 2022 Rathbones Folio Prize.

>>Your copy.

NEW RELEASES

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au $30>>RNZ interview.

This well-illustrated book examines how images of Roman autocrats have influenced art, culture, and the representation of power for more than 2,000 years What does the face of power look like? Who gets commemorated in art and why? And how do we react to statues of politicians we deplore? In this book—against a background of today's "sculpture wars"—Mary Beard tells the story of how for more than two millennia portraits of the rich, powerful, and famous in the western world have been shaped by the image of Roman emperors, especially the "Twelve Caesars," from the ruthless Julius Caesar to the fly-torturing Domitian.

>>Something like this.

>>The world according to Simon Stalenhag.

Menand tells the story of American culture in the pivotal years from the end of World War II to Vietnam and shows how changing economic, technological, and social forces put their mark on creations of the mind. How did elitism and an anti-totalitarian skepticism of passion and ideology give way to a new sensibility defined by freewheeling experimentation and loving the Beatles? How was the ideal of "freedom" applied to causes that ranged from anti-communism and civil rights to radical acts of self-creation via art and even crime? Menand takes us inside Hannah Arendt's Manhattan, the Paris of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Merce Cunningham and John Cage's residencies at North Carolina's Black Mountain College, and the Memphis studio where Sam Phillips and Elvis Presley created a new music for the American teenager. He examines the post war vogue for French existentialism, structuralism and post-structuralism, the rise of abstract expressionism and pop art, Allen Ginsberg's friendship with Lionel Trilling, James Baldwin's transformation into a Civil Rights spokesman, Susan Sontag's challenges to the New York Intellectuals, the defeat of obscenity laws, and the rise of the New Hollywood.

>>In the news today.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

A Good Winter by Gigi Fenster {Reviewed by STELLA} Olga’s helping Lara. They are both looking after the baby because Sophie needs them. Lara and Olga are neighbours. They live in the same building. Sophie, Lara’s daughter, is having a tough time with the new baby. Her husband died six months before their child’s birth. Lara puts her life on hold so she can step in to care for her daughter and new grandchild. Thankfully, there is Olga, so sensible and dependable. Olga, who can come at a moment's notice and is a wonderful support for them all, especially Lara. Gigi Fenster, in A Good Winter, convincingly, and without pause, keeps us in the grips of Olga’s mind and perspective. The novel is Olga’s story — her telling. Through her actions and encounters alone we ‘know’ Lara and her family. As the winter progresses, the two women build their routine, a routine that Olga makes happen, making small adjustments in her previous daily structure, unbeknown to Lara. Olga sees her relationship with Lara as special, unlike the other friends, and her obsession with Lara builds as Winter progresses into Spring. They have their special films, their cafe and funny shared phrases. Olga is enamoured with Lara: she’s the only one who understands. As Sophie improves and her depression ebbs, Olga’s behaviour becomes more erratic and her jealousies simmer just under the edge of her reasonable veneer. Being in Olga’s head is never an easy place, but Fenster keeps us engaged in this discomfort, taking us to parts of Olga’s childhood that are almost out of bounds, that Olga attempts to repress; keeping the monologue tight, and striking an almost humorous note with Olga’s judgemental observations. This is a story of an unsettled mind, of tragedy and abandon, one which is riveting and thrilling, one which doesn’t shy from a building sense of alarm while also gently taking us along, allowing us glimpses into Olga’s past, her desires and sadness. The pace is pitch-perfect, the language, with its cleverly constructed conversations and staccato memory snippets, successfully reflects a troubled mind. As these images, Olga’s memories, some true; others constructed, coalesce on the page and build in the reader’s mind, it becomes increasingly likely that this woman’s obsession with Lara and her deep-seated delusions won't be repressed indefinitely. Olga’s betrayals that she carries deep in the pit of herself are screaming to be released. But what will be the trigger that unpicks the carefully constructed blanket? The new young female tenant who doesn’t know the ‘rules’? Sophie’s terribly selfish trashy friend? The new boyfriend? Or something or someone closer to home? Fenster manages to bring a lightness and freshness to a fraught topic and Olga is completely convincing. A Good Winter was awarded the 2020 Gifkin Prize and is longlisted for this year's Acorn Prize. Highly accomplished, this is a sensational piece of writing about betrayal, the harm of a childhood misunderstood, a life desiring purpose and acknowledgement, and ultimately, the story of a woman undone. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

Aug 9—Fog by Kathryn Scanlan {Reviewed by THOMAS} At what point does literature begin, he wondered, if there is such a thing as literature and if it does at some point begin. Is it not after all the case, he wondered, that we are assailed at all times and in all circumstances by an unbearable infinitude of details that we must somehow resist or ignore or numb ourselves to almost entirely if we are to bear them, we can only be aware of anything the smallest proportion of things and stay alive or stay sane or stay functioning, he thought, we must tell ourselves a very simple story indeed if we are to have any chance of functioning, we must shut out everything else, we must only notice what we look for, what our story lets us look for, he thought, the froth now frothing in his brain, or rather in his mind, our stories blot stuff out so that we can live, at least a little longer. We are so easily overwhelmed and in the end we are all overwhelmed, the details get us in the end, but until then we cling to our limitations, to the limitations that make the unbearable very slightly bearable, if we are lucky. All thought is deletion. The stories that we think with, he thought, are not possible without an ongoing act of swingeing exclusion, thought is an act of exclusion. What would we put in a diary? What would we put in an essay? What would we put in a novel? If we boil it all down how far can we boil it all down? We find ourselves alive, the details of our life assail us, eventually overwhelm us and destroy us. That’s our story. We die of one detail too many, but if it wasn’t that detail that finished us off it would be another, they are lining up, pressing in, abrading us. Can we resist what we understand, he wondered, to the extent that we even understand it? Is art just this form of resistance? At what point does literature begin, if there is such a thing as literature and if it does at some point begin? Is there something in our life that resists exclusion, something that when the boiling down is done is not boiled completely down? Can we move beyond simplification to a countersimplification, he wondered, and what could this even mean? If Kathryn Scanlan found a stranger’s diary at an auction and she read this diary so often that she felt she almost was its eighty-six-year-old author, if a diary’s keeper is an author, she too became the dairy’s keeper, certainly, at least in some sense, and then if she further edited this dead woman’s year, this dead woman’s words, though the woman was not yet dead, obviously, in the year that she kept the diary, when she was the diary’s keeper, not quite yet dead, whose work do we have in Aug 9—Fog, the boiled down boiled down again, this rendering, this literature, we could call it, rendered from life, here in a two-step rendering process? That is no place for a question mark, he thought. The story of the year is a story of death plucking at an old woman’s life, she loses her husband, her health, her spirits, so to call them, a strange term. The details of her life are the ways in which what she loves is torn away but also these details, often even the same details, are the ways in which this tearing away is resisted, he thought, these details are the ways in which what is loved may be clutched, in which what is loved is saved even while it is borne away. “Turning cooler in eve. We had smoked sausages, fried potatoes & onions. Dr. says it’s a general breaking up of his body. I am bringing in some flowers.” Every very ordinary life, and this is nothing but a very ordinary life, he thought, no life, after all, is anything but a very ordinary life, every very ordinary life is caught in the blast of details that will destroy it but or and these are the very details that enable a resistance to this blast, through literature perhaps, so to call it, resistance is poetry, he thought, an offence against time, a plot against unavoidable loss. We resist time and succeed only when we fail. “Every where glare of ice. We didn’t sleep too good. My pep has left me.” |

Book of the Week. Opium? Caffeine? Mescaline? Michael Pollan explores the ways in which humans use the psychoactive potentials of plants — and these plants' historically formative effect on human culture — in This Is Your Mind on Plants.

>>Changing the way we see the world.

>>The intoxicating garden.

>>Psychedelics and mental issues.

>>Ego, death and plants.

NEW RELEASES

Deep Wheel Orcadia by Harry Josphine Giles $28>>Other books in the series.

>>"I float, I strain, I swim."

>>The Safe Zone.

>>Braver in water than on land.

>>Periods, nature writing and colonialism.

>>A pond of likenesses.

>>NMP on RNZ.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

She's a Killer by Kirsten McDougall {Reviewed by STELLA} Open the covers of Kirsten McDougall’s novel, She’s a Killer, and soak in a shabby Wellington of the near future. Infrastructure is failing, food prices have sky-rocketed, and water is an expensive scarce commodity. Meet Alice, stuck in the same job at enrolments at the university for twenty or so years after giving up on pursuing her psychology studies, badly behaved and bored. Bored because she’s one point off ‘genius’ and her life is crashing in on her. She’s living downstairs from her Antiques Roadshow-obsessed mother who she communicates with by morse code (nice touch), her flat is depressing — there’s a plant growing out of the rotting kitchen bench, her spare room is filled with boxes of unwanted ex-boyfriend stuff, and her view is a rundown running track with rubbish piles at its centre. And, her internal friend ‘Simp’ is back niggling at her with ‘home truths’. The Alice/Simp conversations are fraught and surprisingly entertaining — there’s a constant tussle with this internal monologue, a monologue that sometimes bursts out, verbally, into the rest of the world, turning heads and creating awkward situations for Alice — although, she, Alice, doesn’t seem too bothered by her instability and rather revels in it. When she meets Pablo at the enrolment office — he’s putting in a request for a Russian Literature course — he charms her into a date. Alice is keen on a good dinner, and wouldn’t mind some sex either, with a good looking and intelligent wealthugee. (McDougall may have just coined a new term — a wealthy climate refugee who can buy their way into an accommodating country.) And then comes the twist (this is an eco-thriller): Pablo, surprise, surprise, isn’t who he seems to be, and he has a fifteen-year-old daughter, Erika — a daughter who Alice suddenly finds herself saddled with (but not without excellent financial recompense) for a few days when Pablo has to abruptly leave the country on urgent business. Erika is a point or two smarter than Alice — her IQ is 162 (Alice 159), and an unusual relationship begins to build between the two women. Erika manages to get the flat looking better, arranges installation of rainwater gathering tanks and gets Alice’s mother downstairs for an evening meal. But why? What does Erika really want and what is she up to? Here the plot picks up pace, and the action kicks in. The side stories about Alice, her co-workers, her childhood (and the daughter/mother relationship), her best friend Amy (wife of successful architect and mother to three gifted children), her hedonistic past and her emotional incapacities draw together and gravitate towards the eye of a storm — a storm facilitated by Erika. At times, it seems unbelievable that Alice would venture, and take those closest to her, into a dangerous situation that has no obvious personal advantage. It’s a situation over which she seems to have no or little control, but there is something beguiling about Erika and her cause, especially for a smart, bored woman who sees the inequities but doesn’t necessarily know how to care. Alice may be intellectually gifted, but she's often lacking in emotional intel. Is it Erika’s disdain for the privileged and her ability to act on her beliefs that keeps Alice curious? This eco-thriller set in a not-so-distant and quite believable future Aotearoa, is a cracker of a page-turner, with funny observations of human tropes and snarky behaviour from a not wholly likeable main character. Longlisted for the 2022 Acorn Fiction Prize. |