| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

Diary of a Void by Emi Yagi (translated by Lucy North and David Boyd) {Reviewed by STELLA} A charming if somewhat absurd novel about office life and maternity expectations in contemporary Japan. Ms Shibata, a thirty-something office worker, is tired of working for a manufacturer of cardboard cores (yes, really!) for paper products. Mostly she’s fed up with the expectation from her predominantly male colleagues that she will empty the rubbish bins, fill the photocopier with paper, empty the ashtrays and wash the coffee cups. So one day she feigns pregnancy to get out of cleaning up after a meeting. Claiming it’s making her feel nauseous, she suddenly finds herself off the hook from these menial tasks, which now fall to the male office junior who has recently started at the company. There’s a problem though — she has to keep up the pretence. And so she does. This is a hilarious tale of subterfuge, interspersed with a surprisingly sharp analysis of impending motherhood, as well as the interest (sometimes intrusive) that being pregnant in the workplace, and, by extension, society, garners for women. Even though she will be a single mother, there is no stigma — more a sense of concern and care. The drawback to pretending to be pregnant is the attention, a different set of expectations, she draws from her office colleagues — some of them, well, one, in particular, are too keen on advice and suggestions of names. On the other hand, she now gets to knock off at 5 pm — a big advantage in the 'long-hours office' world she inhabits: others do the extra tasks and she gets to go to free aerobic classes. There’s a special tag for her bag indicating her status to the world at large, which entitles her to a seat on the train and more consideration as now she’s contributing to the future generation. And, if she pulls it off, there’s a year’s maternity leave — without the overtime: it will be a bit tight but a good budget will ensure it’s enough. Though this is hardly Ms Shibata’s game — there’s no intention of swindling. There’s no plan. In fact, you get the distinct impression that this woman is adrift in a large city, anonymous and ground down by a dull job with few prospects. She’s lonely. The expectant mothers’ fitness class gives her a sense of community, but, of course, she’s also adrift here — not really one of the clan. As she reaches ‘full term’ — she’s been eating for two and stuffing her clothes — there are small moments where she’s so convincing that she’s almost convinced herself. Ms Shibata is in phantom pregnancy territory — it has her slightly derailed, and for a moment the reader worries for her sanity. Emi Yagi's Diary of a Void cleverly takes the concept of time and recording a pregnancy (every expectant mother in Japan is given a government-regulation handbook similar to our Plunket book) to an extreme level — a diary of nothing — in an attempt to highlight the double standards of office culture and the role of motherhood in Japan. Entertaining, ironic and surprisingly endearing. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

Multiple Choice by Alejandro Zambra (translated by Megan McDowell) {Reviewed by THOMAS} If texts are not completed until they are read, and if the realisation of those texts is largely dependent upon the contexts in which they are read, each reading becomes a test, both of the text and of the reader (the author by this time having taken refuge in the past (a state indistinguishable from death)). In Zambra's clever, ironic and poignant book, a series of increasingly lengthy texts are presented with accompanying multi-choice questions (modelled on the Chilean Academic Aptitude test, a multi-choice university entrance examination [!]) which demand that the reader insert, exclude, suppress, complete or 'interpret' elements of the text. Any provision of choice combined with the restriction to set choices and the impulsion to choose is not only a way of assessing an aspirant but a way of moulding that aspirant's thinking into categories set by whatever is the relevant authority. This thought-moulding, the reader's constant awareness while reading that they will be judged and categorised but not knowing for what, the constant possibility that one's experience may have aspects of it erased or re-ordered by agents of authority (with whom even the reader may be complicit under unforeseen circumstances) but not knowing in advance which aspects these may be have especial resonance with the Chilean dictatorship in which Zambra grew up, but are always all about us for, after all, is not the erasure or addition of detail concerning the past (and these stories are all written in the past tense) an inescapable part of the tussle for reality that takes place constantly all around us at all levels, personal, interpersonal, historical, political? The book is also 'about' writing stories: how does the inclusion, exclusion and ordering of detail affect the reader's understanding of and response to a text? These are considerations a writer is constantly, dauntingly faced with and which they usually in the first instance answer from their own experience as a reader (in this case the author is incapable of benefitting from criticism by being embedded in the past (a state indistinguishable from death) but has made himself immune to judgement by allowing for all possibilities and committing himself to none (or at least seemingly: is this political prevarication or subversive smokescreen?). As well as being 'about' all these sorts of things, the book is fun and funny, and it can also be read with enjoyment on the level of the spectacle. |

NEW RELEASES

Thirty-four-year-old Ms Shibata works for a company manufacturing cardboard tubes and paper cores in Tokyo. Her job is relatively secure: she's a full-time employee, and the company has a better reputation than her previous workplace, where she was subject to sexual harassment by clients and colleagues. But the job requires working overtime almost every day. Most frustratingly, as the only woman, there's the unspoken expectation that Ms Shibata will handle all the menial chores: serving coffee during meetings, cleaning the kitchenette, coordinating all the gifts sent to the company, emptying the bins. One day, exasperated and fed up, Ms Shibata announces that she can't clear away her colleagues' dirty cups, because she's pregnant. She isn't. But her 'news' brings results: a sudden change in the way she's treated. Immediately a new life begins. How long can she sustain this deception?

"Diary of a Void advances one of the most passionate cases I've ever read for female interiority, for women's creative pulse and rich inner life." —The New Yorker

Recently unearthed from the ground, Marble leaves her new lover in Copenhagen and travels to Athens. The city is overflowing with colour, steam and fragrance, cats cry like babies at night, the economic crisis is raging. In this volatile landscape, Marble grasps the world by exploring its immediate surfaces. Capturing specks of colour on ancient sculptures in the Acropolis Museum with an infrared camera, she simultaneously traces the pioneering sculptor Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen, who spent several months in the same place 110 years earlier. Far away from her husband and children, Carl-Nielsen showed that Archaic sculptures were originally painted in bright colours — a feat which meant defying Victorian gender roles and jeopardising her marriage. Marble is a galvanizing novel about the materials life is made of, about korai and sponge diving, about looking and looking again.

>>Read Thomas's review.

>>My Dinner with André.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

Granta 158: In the Family edited by Sigrid Rausing {Reviewed by STELLA} Granta was a publication which I would seek out in the second-hand bookshop when I was a student. It didn’t matter if it was a recent edition or not, for without fail it would be interesting and introduce me to new writers. Its thematic formula made some issues more appealing than others, but with its combination of fiction, non-fiction and photo essays it was always worth investigating. The latest Granta — Issue 158 — is titled In the Family. It opens with a story from Fatima Bhutto about her pregnant dog during the pandemic when they escaped the city to sit out the worst of the unfolding events of 2020. The vet can’t see her dog unless it’s an emergency. In this piece of writing Bhutto’s experience of helplessness leads her to reflect on the connection between animals and humans. As she explores this she delves into her own family connections (many of her family members have met violent deaths, including her father), to consider the question — what is a good life? Entitled 'The Hour of the Wolf', its nuanced texture keeps giving at an intimate level, is philosophical, draws on political history, and is also right in the moment. It's a clever essay that can hold so much in a few pages. Following on from this is an excerpt from Pure Colour by the excellent Shelia Heti. In this passage, the narrator reflects on a father’s death: the kaleidoscope of emotions, the release, the ambivalence, relief and sadness. “His spirit was sly as a fox, the way it snuck into her — the way it stealthily, like a fox, moved into her. She can still feel it there. sometimes, sneaking about. It is a great joy to have his spirit inside her, like the brightest and youngest fox!” If you know Heti’s work, you will appreciate this. She never fails to take you somewhere unexpected without leaving you behind. Julie Hecht’s 'The Emperor Concerto' is a sharp story about siblings, mother/daughter relationships, and the tang of memory laced with little pinpricks that sits just right. I haven’t read anything by Hecht before, so here’s my discovery and someone I’ll be following up on. And this is what makes a literary journal like Granta so relevant and excellent. There’s something familiar and always something new. The writing is varied in style and structure, so you can dip in and dip out as your mood takes you. And if you feel like a visual hit, the photo essays add extra flavour. Sometimes dramatic, often quotidian, they capture moments that strike a note of right here, right now — a social document which leaves you to make the connections. Worth picking up, always. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

W, Or, The Memory of Childhood by Georges Perec {Reviewed by THOMAS} “I write: I write because we lived together, because I was once amongst them, a shadow amongst their shadows, a body close to their bodies. I write because they left in me their indelible mark, whose trace is writing. Their memory is dead in writing; writing is the memory of their death and the assertion of my life.” Both of Perec’s parents were killed in the 1939-1945 war, his father early on as a French soldier, and, soon after, his mother sent to a death camp. Their young son was smuggled out of Paris and spent the war years in a series of children’s homes and safe villages. “My childhood belongs to those things which I know I don’t know much about,” he writes. W alternates two narratives, the first an attempt by Perec to set down the memories of his childhood and to examine these not only for their accuracy but in order to learn the way in which memory works. Often factual footnotes work in counterpoint to the ‘remembered’ narrative, underscoring the limitations of the experiences that formed it. Right from birth the pull of the Holocaust is felt upon Perec’s personal biography, and his story is being shaped by this force, sucking at it, sucking his family and all stability away. Sometimes he attaches to himself experiences of which he was merely a witness, the memories transformed by remembering and by remembering the remembering, and so forth, and by the infection of memories by extraneous imaginative details. “Excess detail is all that is needed to ruin a memory.” The absences around which these memories circulate fill the narrative with suppressed emotion. The other narrative begins as a sort of mystery novel in Part One, telling how one Gaspard Winckler is engaged by a mysterious stranger to track down the fate of the boy whose name he had unknowingly assumed and who had gone missing with his parents in the vicinity of Terra del Fuego where they had gone in search of an experience that would relieve the boy’s mutism. In Part 2, the tone changes to that of an encyclopedia and we begin to learn of the customs, laws and practices of the land of W, isolated in the vicinity of Terra del Fuego, a society organised exclusively around the principles of sport, “a nation of athletes where Sport and life unite in a single magnificent effort.” Perec tells us that ‘W’ was invented by him as a child as a focus for his imagination and mathematical abilities during a time when his actual world and his imaginative world were far apart, his mind filled with “human figures unrelated to the ground which was supposed to support them, disengaged wheels rotating in the void” as he longed for an ordinary life “like in the storybooks”. Life and sport on W are governed by a very complex system of competition, ‘villages’ and Games, “the sole aim to heighten competitiveness or, to put it another way, to glorify victory.” It is not long before we begin to be uncomfortable with some of the laws and customs of W, for instance, just as winners are lauded, so are losers punished, and all individual proper names are banned on W, with athletes being nameless (apart from an alphanumeric serial number) unless their winnings entitle them to bear, for a time, the name of one of the first champions of their event, for “an athlete is no more and no less than his victories.” Perec intimates that there is no dividing line between a rationally organised society valuing competition and fascism, the first eliding into the second as a necessary result of its own values brought to their logical conclusions. “The more the winners are lauded, the more the losers are punished.” The athletes are motivated to peak performance by systematic injustice: “The Law is implacable but the Law is unpredictable.” Mating makes a sport of rape, and aging Veterans who can no longer compete and do not find positions as menial ‘officials’ are cast out and forced to “tear at corpses with their teeth” to stay alive. Perec’s childhood fantasy reveals the horrors his memoir is unable to face directly. We learn that the athletes wear striped uniforms, that some compete tarred and feathered or are forced to jump into manure by “judges with whips and cudgels.” We learn that the athletes are little more than skin and bone, and that their performances are consequently less than impressive. As the two strands of the book come together at the end, Perec tells of reading of the Nazi punishment camps where the torture of the inmates was termed ‘sport’ by their tormentors. The account of W ends with the speculation that at some time in the future someone will come through the walls that isolate the sporting nation and find nothing but “piles of gold teeth, rings and spectacles, thousands and thousands of clothes in heaps, dusty card indexes, and stocks of poor-quality soap.” |

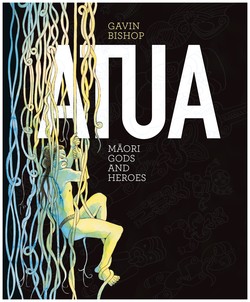

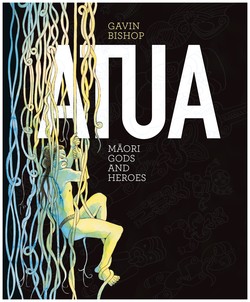

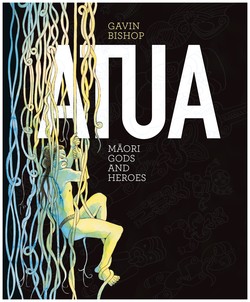

Book of the Week. Gavin Bishop's distinctively beautiful and informative book Atua: Māori Gods and Heroes has just been awarded the premier Margaret Mahy Book of the Year at the 2022 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.

This wonderful large-format book belongs on every child's—and every adult's—bookshelf. From creation to migration, lively illustrations and text tell the unique stories of Aotearoa's gods, demigods and heroes.

>>Your copy (or one to give away)—more stock will arrive in a few days.

>>The book belongs alongside the wonderful Aotearoa: The New Zealand story and Wildlife of Aotearoa.

NEW RELEASES

Either/Or by Elif Batuman $37"Batuman has a gift for making the universe seem, somehow, like the benevolent and witty literary seminar you wish it were. This novel wins you over in a million micro-observations." —The New York Times

"Our funniest overthinker — and the queen of the campus novel. Selin is a droll and disarming narrator, and takes her place as one of the finest hapless scholars in the literary canon." —Sunday Times

>>The need for novels.

>>The ethical versus the aesthetic life.

>>Books are magic.

>>Either/Both.

>>Controlling words.

>>We first met Selin in The Idiot.

In his third poetry collection, award-winning poet Tim Upperton takes us to the end of the driveway, over the Manawatū – twisting like an eel – and on to Topeka and Paris. These are poems of acid wit (‘I have been to Paris / and apart from the architecture / and the food and some very fine cemeteries / and of course the language / it’s quite like Palmerston North’), intimations of loss (‘The wrong life cannot be lived rightly. I should know’) and unexpected resolution (‘like pollen, / like grace so available nobody wanted it’). Unpredictable and restive, A Riderless Horse stands in the everyday and then runs with it.

The winners in the 2022 NEW ZEALAND BOOK AWARDS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG ADULTS have just been announced.

Atua: Māori Gods and Heroes written and illustrated by Gavin Bishop (published by Puffin, Penguin Random House)

Atua is an instant classic, a 'must have' for every Kiwi household and library, that is packaged in stunning production values. Every element of the generously sized masterpiece is carefully considered. With impeccable illustrations in Gavin Bishop’s unmistakable style, it captures the personalities of the many gods and heroes. Each section has a fresh look, from the dense matte blackness of the first pages reflecting Te Kore, nothingness, to the startling blue backgrounds of the migration, with the glorious Te Rā – the sun, between. Atua is much more than a list of Gods and legendary heroes – it’s a family tree, presented with power and simplicity. The text is never overstated, with the glory of the illustrations as the primary mode of storytelling, rewarding the reader who closely examines them. There is a sense of magic about this book, right from the front cover. Atua is a taonga for this generation and the next.

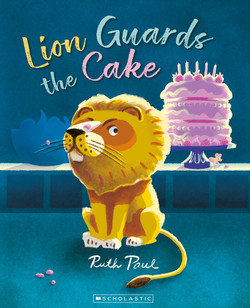

Lion Guards the Cake written and illustrated by Ruth Paul (published by Scholastic New Zealand)

If a good picture book is a symbiosis of story and illustration, a stand-out picture book is one which includes that all-important third symbiotic element – the reader. Lion Guards the Cake is a sweetly irresistible story that invites readers to be both witness and accomplice to lion’s furtive adventures and faux heroism as he upends the notion of duty. Its faultless, inventive rhyme, complemented by rich, silhouetted illustrations, engages the reader with effortless ease and a twinkle in its eye. This is confident storytelling of the highest calibre – a joyful read-out-loud which also rewards a more intimate and leisurely reading.

Wright Family Foundation Esther Glen Award for Junior Fiction

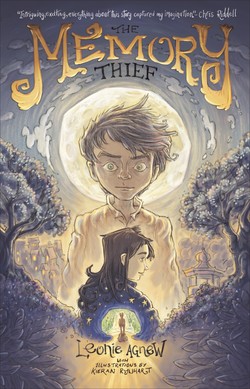

The Memory Thief written by Leonie Agnew (published by Puffin, Penguin Random House)

From its eye-catching cover to the final conclusion, The Memory Thief is a stunning story that captures the reader early and holds them in an embrace of wonder, intrigue and imagination. The judges all agreed on the skill and writing craft of the author, sharing an extra depth and quality of language in this novel. Unique but perfectly believable at the same time, The Memory Thief steps into another world whilst still inside our own. Memories themselves are both villains and heroes as they are taken or returned. The handling of a common illness, with its thought-provoking and original twist, is deftly handled and beautifully written.

Learning to Love Blue written by Saradha Koirala (published by Record Press)

Learning to Love Blue is a celebration of finding independence in a new city. As Paige moves from Wellington and the comfort of friends and family to Melbourne, she must navigate new friendships and romantic relationships, all the while navigating her complicated feelings about her absent Mum. Saradha Koirala conveys all the mixed emotion of this setting in a way that is realistic, compassionate, and firmly placed in the journey into adulthood. Relatable at every turn, Learning to Love Blue draws you into Paige’s journey through Melbourne’s streets, bands, record and coffee shops, and has you rooting for her to the very end.

Atua: Māori Gods and Heroes written and illustrated by Gavin Bishop (published by: Puffin, Penguin Random House)

Variously described by the judges as a taonga, an instant classic and a 'must have' for every Kiwi household, Atua is a family tree for all New Zealanders. These tales of gods and heroes, both familiar and unfamiliar, are richly and emotively told with a novelist's eye for potent detail and the gentle authority of a master storyteller. It is a book designed to be treasured, with stunning production values and a mind-boggling attention to design detail that perfectly complement and enhance the powerfully emotive illustrations. A work of undoubted mastery, Atua is a rare gem indeed.

Atua: Māori Gods and Heroes illustrated and written by Gavin Bishop (published by: Puffin, Penguin Random House)

Atua is connected through time and place. Every page and section reveals more about the Māori world. The artwork of Atua is exceptional, with watercolours that mimic elements seen in the taiao or environment, and a use of shapes and traditional Māori patterns and motifs that elevates it to a class of its own. These illustrations create a mauri or life force unique to this book. Even the cover reveals a deliberate intention to reflect pūrākau Māori, with overglossed atua figures on a velvety blackness that connects us to te pō, the beginning of time and existence. Both the illustrator and the publisher should be very proud of the taonga that they have created.

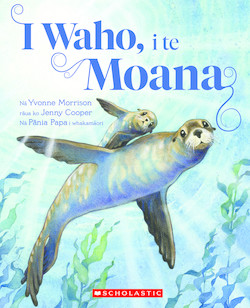

I Waho, i te Moana written by Yvonne Morrison, illustrated by Jenny Cooper, translated by Pānia Papa (published by Scholastic New Zealand)

In I Waho, i te Moana, the many sea creatures of the moana of Aotearoa are brought to life, with beautiful illustrations that highlight the interactions between sea creatures and their world. The story allows children to relate to these creatures, and understand their roles as kaitiaki within the realm of Tangaroa. There is a beautiful flow to the reo, which reflects the expertise of the translator. Te reo Māori will transcend the imagination and encourage interactions between tamariki and parents who read this wonderful story. This will support growth in te reo Māori capacity of both tamariki and parents who are at the conversational level.

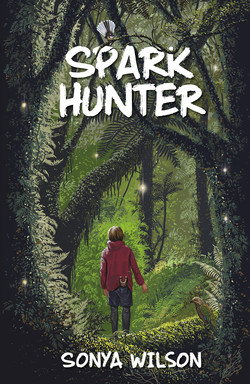

Spark Hunter written by Sonya Wilson (published by The Cuba Press)

Perfectly pitched for middle fiction readers, Spark Hunter weaves history, culture, conservation, humour, tension and adventure into her story of Nissa Marshall, who has always known there is more to the Fiordland Bush than meets the eye. While leaning into the fantastic just enough to encourage the imagination, the inclusion of archival excerpts will spark keen readers to hunt out their own discoveries within the mysterious history of this corner of Aotearoa. Making this story’s light shine bright is te reo Māori blended throughout and a cast of supporting characters that are easily recognisable as classmates, teachers, and friends.

Find out what we've been reading and recommending—and what you will soon be reading and recommending—in our latest NEWSLETTER.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

The Library of the Dead by T.L. Huchu {Reviewed by STELLA} It’s Edinburgh and the ghosts are restless. Ropa has left school to make a meagre living as a ghostalker. She needs to support her Gran and little sister. The ghosts who aren’t quite done with the mortal earth seek out a ghostalker — a passer of messages — to communicate with the living, usually their family members. There are wrongs to right, wills to be instructed, or all sorts of petty family negotiations to be navigated. Ropa is out on her patch, minding her own business, when Nicola, a distraught mother, recently deceased, asks her to find her missing boy. Detective work isn’t Ropa’s usual game and money isn’t forthcoming, but one thing leads to another and she’s in the thick of things. Juggling the bills, keeping the tiny caravan (home) in order, getting Izwa to school and keeping her hustle going keeps her busy, and life is just about to get more complicated. A chance encounter with Jomo, a mate from school, finds her sneaking into an exclusive library under the streets of this dystopian Edinburgh. And getting caught was not the plan, especially when it might lead to her own ghosting. Surprisingly, rather than be punished for her crime, she is given membership to the Library. There’s something magical about Ropa — she is a ghostalker, but you get the distinct impression that there’s more she’s inherited from her mysterious and magical Gran. With her new friend Priya and Jomo in tow, the teens start to unpick the mystery of the disappearing children. And strange and creepy it is. Some of the snatched children find their way home but the change in them is startling — hollowed out and listless, they are old before their time. Add to these scares, The Midnight Milkman (not one you want delivering to your house), a haunted house that holds you by an umbilicus sucked down into a cellar, the eerie in-between ‘everyThere’ underworld, and the excellent, yet disconcerting, Library of the Dead (which in book one we are briefly introduced to). This Edinburgh is a land of post-civil-war destruction, restricted resources and gated wealth. Its inhabitants are lively and diverse. Ropa with her green dreadlocks and black lipstick doesn’t take any stick, Jomo is good-natured and loyal, while Priya, a wheelchair-bound adrenaline junkie, knows her way around on the street and in the lab. The stage is set for the 'Edinburgh Nights' series. Dip your toes in but watch out for the milk — more to come. Plenty of thrills and spooks, with witty dialogue and an underlying commentary on privilege. Fantasy for those who like Ben Aaronovitch’s 'River of London' series and Jonathan Stroud’s 'Lockwood & Co'. Great for adults and teens. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

The Dominant Animal by Kathryn Scanlan {Reviewed by THOMAS} He was careful not to write a review that was longer than the stories in the book he was reviewing, but he was uncertain how he could do this. Uncertain seems more of an introspective word than careful, for some reason, and is therefore unsuitable for use in a review of a book which contains no introspection, or at least displays no introspection. This is not to say that the characters are not propelled by forces deep below the surfaces of their appearances, they are propelled entirely by such deep forces, unconscious compulsions, so to call them, we all have them, or similar ones, but these are not manifest in anything but action, action and appearances also, both austerely told, or seemingly so, briefly, directly, barely, or something to that effect, each of the forty stories, he thinks it is around forty stories, told like a folk or fairy tale, without anything unnecessary, without elaboration, like a folk or fairy tale in which someone, the narrator, so to call her, is trapped in the first person. Folk and fairy tales are never told in the first person because the first person is a trap, or trapped, there in the mechanism of the story, told in the past tense, unalterable, and, like fairy tales, Scanlan’s forty stories are about the relations of power, as the title suggests, about the struggle for dominance that is the basis of all stories. All that happens happens as if by instinct, or by reflex, awareness lags, is only good for telling a story and only in the past tense, and, as with all stories, as with all relations of power, as with all struggles for dominance, everything in the past tense is at once horrible and ludicrous. And the same goes for the present. The horrible is ludicrous, the ludicrous is horrible, there are no other modes of being. All other modes are modes of non-being, if there are other modes, he supposed, fictional modes, perhaps, but he was not sure. That which we see in animals, the tooth-and-nail struggle, so to call it, the immediacy of all response, the inescapability of all compulsion, the way of nature, the cruelty, so to call it, what we call cruelty, is mainly true of us, he thought, without introspection he hoped, that which we affect to see in animals we see only of ourselves, is not apt of animals, who in any case have the advantage over us of seldom being capable either of deception or of self-deception. Just like objects, he thought, Scanlan gives objects the same agency as persons, not by giving agency to objects but by removing it from persons, or by recognising its absence, persons are just objects moving in rather complex ways, scudded on by some force, momentum, compulsion, whatever, but no freer to be otherwise or do otherwise than an object thrown at a wall, notable primarily through the effects of our velocity. Scalan is master of the velocity of her prose, honed to sharpness, careful, devastating, puncturing the imposed limit of the conscious to deliver the reader precisely at the point where rationality, or what passes by that name, flounders in what lies beyond, behind, beneath, or wherever, the point where the unsayable is both revealed and annulled. Think Fleur Jaeggy, Lydia Davis, Diane Williams, he thought, these authors share a sensibility both verbal and incisive, but Scalan’s sentences are no-one’s but her own, she who ends a story, “I watched the man drive away in his glossy, valuable car and prayed he might be met with some misfortune. Due to a major failing — the pathological poverty of my imagination — I could not call to mind anything more specific than that.” |

>>Read an extract.

>>Skin and sinew and breath and longing.

>>In praise of visionary women.

>>Cramped destiny.

>>Long-listed for the 2022 Booker Prize.

>>Your copy.

NEW RELEASES

or in English. Simple text and lovely illustrations convey the feelings of both dog and humans, and show us a beautiful friendship.

>>Have a look inside!

>>"Ferociously intelligent."

>>BWV 224.

>>See also Geoffrey Wheatcroft's Churchill's Shadow.

BOOKS @ VOLUME #289 (29.7.22)

Read our latest NEWSLETTER and find out what we've been reading and recommending.

Full of provocative questions about the relationships between life and art, neurology and computer programming, weaving and language, thinking and feeling, acting and observing, our Book of the Week very appropriately leaves these questions open and active in the reader's mind. Amalie Smith's intriguing double-stranded novel THREAD RIPPER (translated from the Danish by Jennifer Russell) reaches both backwards and forwards in time as a tapestry weaver works on a large commission and, drawing on everything from her personal life to her experiments in artificial intelligence, speculates on the possibilities of what Ada Lovelace called 'the calculus of the nervous system'.

>>Read Thomas's review.

>>On translating the novel.

>>Flora digitalica (working on the commission).

>>Some sample pages are here (scroll down until you find them).

>>Looking through a series of mirrors,

>>Get your copy now.

>>Marble.

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

Thread Ripper by Amalie Smith (translated by Jennifer Russell) {Reviewed by THOMAS} Perhaps, he thought in a rare moment of self-reflection, or in a moment of rare self-reflection, he wasn’t sure which, I have become so accustomed to writing my so-called fictional reviews, to writing my so-called reviews in a fictional manner or even, more confusingly, in an autofictional manner so that they are not immediately recognised as the fictions they are, that I have proverbialised myself into a corner and am incapable of writing a straight review, if there is even such a thing, or a review just written as a review, there might be such a thing as that, he thought, without the novelistic trappings of my approach, my distancing and deflection tricks, my wriggling away from the task at hand and from the possibility that I am not up to the task at hand, he thought, perhaps all my trickeration, so to call it, is just a way of concealing my incapability, from myself at least for surely no-one else is fooled, he thought. None of this helped, he thought, this self-reflection, so to call it, makes me more incapable rather than less, makes anything that might pass for a review, or even for a meta-review, less possible, I have thought myself to a standstill, he thought, unless of course I create a fictional reviewer to write the reviews for me, a fictional reviewer who could write a straight review, a review written as a review, that elusive goal that for me is now unreachable, at least without some trickeration, I have got to the point at which only a fake reviewer can write a real review. Anyway, anyone but me. I wonder how my fictional reviewer will approach this book, Thread Ripper, he thought. Thread Ripper is written in two parallel sequences or threads on the facing pages of each opening, and each of those threads has its own approach to the matters that inform them both. My reviewer would probably find themselves obliged to begin or find it convenient to begin with a description of how the verso pages carry an account, if that is the right word, of the author’s researches and considerations of the history of weaving and computer programming, which turn out to be the same thing, at least in the author’s concurrent artistic practice, so to call it, here also described, and which turn out to be the same thing also as neurology and linguistics, or at least to have typological parallels to neurology and linguistics, if these even warrant separate terms, which the fictional reviewer may speculate on at some length, or not, these recto pages deal with matters outside the author’s head, matters of what could be termed fact, even though the term fact could be applied in this instance to some quite interesting philosophical speculations, speculations about things that may actually be the case, which, for the fictional reviewer, is as good a definition of the term as any. The recto pages are concerned with problems of knowing, the fictional reviewer may begin, or may conclude, whereas the verso pages are concerned with problems of feeling, so to call it, not that in either case should we assume the so-called problems to be necessarily problematic, although in many cases in both strands they are, the recto pages are concerned with what is going on inside the author’s head, with matters subject to temporal mutabilities, temporal mutabilities being an example, or being examples, of the sort of words a fictional reviewer might use when writing a review as a review but not making a very good job of it, though it is unclear whose fault that might be, does he have a responsibility for the performance of this fictional reviewer he has devised to do his job, he supposed he did have some such responsibility but he couldn’t help starting to wonder if successfully creating a character who fails to write well might be more of a success than a failure, though it would be, he supposed, a failure at his stated aim of achieving by the employment of a fictional reviewer the sort of straight review that he found himself these days incapable of writing, he wanted the fictional reviewer to write a real review, after all, a fictional review, which would not need to be actually written and which in this instance he could easily refer to as being wholly positive about this interesting book Thread Ripper, which he has read and enjoyed and which started in his mind, if it warrants to be so called, some quite interesting speculations and chains of thought of his own, and which he could suppose, to make his task easier, his fictional reviewer has also read and enjoyed, they are not so different after all, he thought, such a fictional review would not realise his intention or fulfil the purpose of the reviewer, he had intended the fictional reviewer to review the book in a straightforward way, even though he, even if this intention was by some chance realised, looked as if he would in any case treat the whole exercise, to his shame, as so often, as something of a sentence gymnasium. He would like to write in a straightforward way, he thought, to say, in this instance, I like this book and what is more I think you should buy it because I think you would like it too, but he could not help making the whole exercise into a sentence gymnasium, I never can resist a sentence gymnasium, he thought, these days less than ever, show me a sentence gymnasium or some relatively straightforward task that I could treat as a sentence gymnasium, pretty much anything can be so treated, he realised, and I am lost, he thought, whatever I attempt I fail, I am lost in the fractals of my sentence gymnasiums, or sentence gymnasia, rather, he corrected himself, my plight is worse than I thought, he thought. In Thread Ripper the author on the verso dreams, the fictional reviewer might point out, he thought, or he hoped the fictional reviewer would point out or remember to point out even if they didn’t get so far as to actually point out, according to the verso pages the author dreams and longs, and the author on the recto pages, if we are not at fault for calling either personage the author, programmes her computer with an algorithm to weave tapestries but also with an algorithm to write poetry, the results of which are included on these recto pages, if the author of those pages is to be believed, he didn’t see why not and he thought it unlikely that his fictional reviewer would have any reservations in regard to the authenticity of these poems, so to call them, or rather to the artificial authorship of the poems and of the so-called ‘artificial’ intelligence behind them, any productive system, any arrangement of parts that can produce something beyond those parts, is a sort of intelligence, he thought, though he evidently hadn’t thought this very hard. All thought is done by something very like a machine, even if this is not very like what we commonly term machines, he reasoned, reducing the meaning of his statement almost to nothing while doing so, it is a good thing I am not writing this review myself, it is a good thing I have a fictional reviewer to write the review, a fictional reviewer whom I can make ridiculous without making myself ridiculous, he thought, unconvincingly he had to admit though he didn’t admit this of course to anyone but himself, the universe is full of mess, a mess we are in a constant struggle to reduce. “The digital has become a source not of order, as we had hoped, but of mess, an accumulation of images and signs that just keeps on growing,” writes the author of Thread Ripper. “For humans it’s a mess; a machine can see right through.” Perhaps there is a difference between machine intelligence, which compounds, and human intelligence, which reduces, he thought briefly and then abandoned this thought, perhaps my fictional reviewer will have this thought and perhaps my fictional reviewer will be able to think it through and make something of it, fictional characters often think better than the authors who invent them, fictional characters are themselves a kind of machine for thinking with, artificial characters with artificial thoughts, if there can be such things, perhaps intelligence is the only thing that can never be artificial, he thought, though we might have to change the meanings of several words to make this statement make sense. “I hear on the radio that the human brain at birth is a soup of connections, that language helps us reduce them,” writes the author in Thread Ripper. “The more we learn, the fewer the connections.” Does grammar, then, work as a kind of algorithm, he wondered, or he wondered if his fictional reviewer might be induced to wonder, is it grammar that forms our thoughts by reducing them to the extent that we may affect on occasion to make some sense, whether of not we are right, which is, really, unimportant, the grammar is what matters not the content, is this what Ada Lovelace, who died before she could describe it, referred to as the calculus of the nervous system, could he actually end his sentence with a question mark, he wondered, the question mark that belonged to this Ada Lovelace question, or was he too tangled in his sentence to find its end? |

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

The Last Good Man by Thomas McMullan {Reviewed by STELLA} Be careful what you wish for. In The Last Good Man, Thomas McMullan delves into the slippery world of morality and judgement. We meet Duncan Peck on the road from a devastated and chaotic city. He’s travelling across land, it’s dark and bleak and a wrong step will mean a suffocating drowning in the bog. 'Watch your step' could be the catch cry for this dystopian debut. A dark mass rises from the bog nearby only to be quickly surrounded by a plastic-rain-coated group. A rescue team? Unlikely, with their metal pipes and mob mentality. Yet they draw the miserable man from the bog and head back to a village. Duncan Peck stays mum. There’s a familiar voice — the man he is looking for. Finding him is about to change his life. This last good man. If there was ever such a thing. Duncan arrives in the village and catches up with his brother-in-arms, James Hale. There are recriminations, but also joy at being in each other’s company again. Their past both binds and hangs over them. Each is edgy about looking back, especially Hale who has found his place in this community. A small community of structure, rules (seemingly ‘fair’) and justice as dispensed by all — a true community reckoning as needs demand. How did they get to this order from a world of ecological and economic chaos? The Wall. There it is — visible on the horizon from a great distance, looming over the community in size and psychology. Anyone can write on the wall. If a wrong has been done it will be announced. A mention or two may not warrant any punishment, aside from a wooden piece of furniture attached to a back for a few days. Various men and women go about their daily chores with a lamp, chair or table tied to their backs. Hale tells Duncan Peck early in the piece he better sort out his ropes — make sure he has a good one to ease the troublesomeness of such an imposition. Yet, get your name on the wall in repetition and for more troubling matters, then life might not be so easy, or even possible at all. Accusations have to be acted on — it’s natural justice. Gossip and petty jealousies raise their ugly heads. This is the twitter-sphere writ large in analogue. Technology is a thing of the distant past and, while life is simple, it’s definitely not without complexities and intricate dancing if you want to keep your name from the wall and the attention of the mob that will hunt you down when you make a run for it. You can know many secrets and truths but you would be foolish to voice those in this judgemental village. Thomas McMullan brings us a dark unsettling time, with echoes of Riddley Walker (without the language breakdown) and early Ian McEwan, where human behaviour is both attractive and frightening. Everybody wants to be loved. Everybody wants to be good, but somehow no one can quite pull it off without being bogged down in a sticky mire. Desire and survival are bedfellows Duncan Peck can not ignore if he wants to keep his head. |

NEW RELEASES

Grimmish by Michael Winkler $35This remarkable book challenges our received narratives of historical determinism and the myths of cultural ‘progress’ devised to justify the status quo. If we unshackle ourselves from these preconceptions and look more closely at the evidence, we find a wide array of ways in which humans have lived with each other, and with the natural world. Many of these could provide templates for new forms of social organisation, and lead us to rethink farming, property, cities, democracy, slavery, and civilisation itself. A fascinating and important book, now in paperback.

>>All figured out.

>>Human history gets a rewrite.

>>Collective self-creation.

>>Inequality is not the price of civilisation.

>>American anarchist.

>>What other social systems have there been?

>>Lots of really good videos.

>>Articles by Graeber.

>>Graeber's playlist.

>>Also available as a very satisfying hardback.

>>Other books by David Graeber

>>Read Stella's review of The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne (#1).

>>Book trailer for Book #2.

Wonderworks: Literary invention and the science of stories by Angus Fletcher $28

Finding the Raga: An improvisation on Indian music by Amit Chaudhuri $25

.gif)