Michael Bennett’s finely tuned thriller opens with an historical atrocity before moving to a contemporary series of murders. Detective Hana Westerman is caught between being a good cop or a kupapa collaborator, and the cases become frighteningly personal. Excellently paced and populated by complex characters, this intricate novel centres on conflict between utu and on the aroha, hūmarie and manaaki needed to move forward.

>>Your copy.

Our Book of the Week is Cheon Myeong-Kwan's lively and inventive novel WHALE, translated from Korean by Chi-Young Kim. On listing the book for the 2023 International Booker Prize, the judges described it as "a carnivalesque fairy tale that celebrates independence and enterprise, a picaresque quest through Korea’s landscapes and history, Whale is a riot of a book. Cheon Myeong-Kwan’s vivid characters are foolish but wise, awful but endearing, and always irrepressible. This is a hymn to restlessness and self-transformation."

>>Read an extract.

>>Part of the world.

>>Revenge plays.

>>The news in Korea.

>>Your copy of Whale.

>>Other books long-listed for the 2023 International Booker Prize.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

“Call me Bathsheba,” are the first lines of this inventive novel mimicking another famous story. Patrick Ness’s And the Ocean Was Our Sky is a stunning wonder of a story. In this inverse Moby-Dick, we are introduced to a pod of whales that hunt man. In this world, the sea is the right way up and our sky is the Abyss. The action takes place in and on the ocean as we travel with the whales. Our narrator Bathsheba is the Third Apprentice under the lead of Captain Alexandra — a fearless giant of a whale, a harpoon embedded in her head, survivor of numerous battles with man. When the pod come across a wrecked human ship, bodies afloat, drowned, it is difficult to tell whether this is the work of man or whale. If whale, it is messy — wasteful — the bodies haven’t been harvested for their teeth nor bone. If man, why? As they approach the ship, a hand clutching a disc protruding from the capsized hull is spied: a hand that belongs to a young man — a prisoner — called Demetrius, and he has a message about (or from) Toby Wick - the nemesis of the whales. Toby Wick, feared and hated by man and whale, is a mysterious and vicious hunter — a legend. None who have seen him live to tell the tale of who he is and the powers he can summon to win every battle. Alexandra, obsessed with overcoming Toby Wick, is determined to fulfill a prophecy — one that has been passed down through generations. The great Toby Wick will be confronted. Demetrius is kept alive under the ocean and Bathsheba is commanded to interrogate him. A relationship builds between man and whale - for centuries prejudice and hatred have reigned supreme between the species, each hunting the other, each having just cause for revenge. Yet Bathsheba is intrigued by this meeting with Demetrius, who is merely a pawn in Toby Wick’s game — not a hunter, not an enemy. As Bathsheba’s loyalty is tested, the pod swim closer to their meeting with the mythic Toby Wick. What awaits them is fearsome and surprising. And the Ocean Was Our Sky is an epic journey for Bathsheba — physically but even more so philosophically and emotionally. Her interactions with Demetrius and the encounter with Toby Wick will change her forever, and the relationship between man and whale will create a new prophecy. This mind-bending story about fear, prejudice, loyalty and legend is brilliantly and beautifully illustrated by Rovina Cai. It’s a tale for any age much like Ness’s excellent A Monster Calls. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

| Poetics of Work by Noémi Lefebvre (translated from French by Sophie Lewis) {Reviewed by THOMAS} How should we occupy ourselves, he wondered, whatever that means, lest we be occupied by someone else, or something else, how do we keep our feet, if our feet at least may be said to be our own to keep, by leaning into the onslaught or by letting it wash through us? Too many metaphors, if they’re even metaphors, he thought, too much thought thought for us by the language we use to think the thoughts, he thought, too many ready-made phrases, who makes them and why do they make them, and what are their effects on us, he wondered, where is the power that I thought was mine, where is the meaning that I meant to mean, how can I reclaim the words I speak from those against whom I would speak them? No hope otherwise. The narrator of Noémi Lefebvre’s Poetics of Work happens to be reading Viktor Klemperer’s Language of the Third Reich, in which Klemperer demonstrates that the success of, and the ongoing threat from, Nazism arose from changes wrought on the ways in which language was used and thus upon the ways people thought. Whoever controls language controls thought, he thought, Klemperer providing examples, authority exerts its power through linguistic mutation, but maybe, he thought, power can be resisted by the same means, resistance is poetry, he shouted, well, perhaps, or at least a bit of judicious editing could be effective in the struggle, he thought, rummaging in the draw of his desk for his blue pencil, it’s in here somewhere. Fascism depends on buzzwords, says Klemperer, buzzwords preclude thought, and the first step in fighting fascism, says Klemperer, is to challenge the use of these buzzwords, to re-establish the content of discourse, to rescue the particular from the buzzword. Could he think of some current examples of such buzzwords, he wondered, and he thought that perhaps he could, perhaps, he thought, if terms such as the buzzword ‘woke’ or the buzzword ‘cancel’ were removed from discourse and the wielders of these buzzwords had no recourse but to say in plain language what they meant, these once-were-wielders would be revealed to be either ludicrous or dangerous or both ludicrous and dangerous and the particulars of a given situation could be more clearly discussed. That is a subversive thought, he thought, to edit is to unpick power. “There isn’t a lot of poetry these days, I said to my father,” says the narrator at the beginning of Poetics of Work. A state of emergency has been declared in France, it is 2015, terror attacks have resulted in a surge of nationalism, intolerance, police brutality, the narrator, reading Klemperer as I have already said, is aware of the ways in which language has been mutated to control thought, power acts first through language and then turns up as the special police, it seems. What purchase has poetry in a language also used to describe police weaponry, the narrator wonders. “I could feel from the general climate that imagination was being blocked and thought paralysed by national unity in the name of Freedom, and freedom co-opted as a reason to have more of it.” Freedom has become a buzzword, it no longer means what we thought it meant, but even, perhaps, well evidently, its opposite. “Security being the first of freedoms, according to the Minister of the Interior, for you have to work.” You have to work, is this the case, the narrator wonders, you have to work and by working you become part of that which harms you. The book progresses as a series of exchanges between the narrator and their father, the internal voice of their father, of all that is inherited, of Europe, of the compromise between capital and culture, of all that takes things at once too seriously and nowhere near seriously enough. “He’s there in my eyes, he hunches my shoulders, slows my stride, spreads out before me his superior grasp of all things,” the narrator says, embedded in their father, struggling to think a thought not thought for them by their father, their struggle is a struggle for voice, as all struggles are. “I am like my father but much less good, my father can do anything because he does nothing, while I do nothing because I don’t know how to defend a person who’s being crushed and dragged along the ground and kicked to a pulp with complete impunity, nor do I know how to get a job or write a CV or any biography, nor even poetry, not a single line of it.” What hope is there? Is it possible to find “non-culture-sector poetry”, the narrator wonders, or even to write this “non-culture-sector” poetry if there could be such a thing? What sort of poetry can be used to come to grips with even the minor crises of late capitalism, for instance, if any of the crises of late capitalism can be considered minor? “I watched the water flow south, and the swans driven by their insignificance, deaf and blind to the basic shapes of the food-processing industry, ignorant that they, poor sods, were beholden to market price variation over the kilo of feathers and to the planned obsolescence of ornamental fowls.” The book sporadically and ironically gestures towards being some sort of treatise on poetry, it even has a few brief “lessons,” or maxims, but these are too half-hearted and impermanent to be either lessons or maxims, perhaps, he thought, they might qualify as antilessons or antimaxims, if such things could be imagined, though possibly they ironise an indifference to both. “Indifference is a contemplative state, my father said one day when he’d been drinking.” Doing nothing because there is nothing to be done, or, rather, because one cannot see what can be done, is very different from doing nothing from indifference, but the effect is the same, or the lack of effect, so something must be done, the narrator thinks, even if it is the case that nothing can in the end be done. For those to whom language is at once both home and a place of exile, the struggle must be made in language, or for language, resistance is poetry, or poetry is resistance, I have forgotten what I shouted, I will sharpen my blue pencil, after all one must be “someone among everyone,” as the narrator says. “There’s a fair bit of poetry at the moment, I said to my father,” the narrator says at the end of Poetics of Work. “He didn’t reply.” |

NEW RELEASES

Chicanes by Clara Schulmann (translated from French by Anna Clement, Ruth Diver, Lauren Elkin, Jennifer Higgins, Natasha Lehrer, Sophie Lewis, Naima Rashid, and Jessica Spivey) $38>>The voice that cannot be controlled.

>>Read an extract.

>>Other books long-listed for the 2023 International Booker Prize.

Rico, Mark, Paul and Daniel were 13 when the Berlin Wall fell in autumn 1989. Growing up in Leipzig at the time of reunification, they dream of a better life somewhere beyond the brewery quarter. Every night they roam the streets, partying, rioting, running away from their fears, their parents and the future, fighting to exist, killing time. They drink, steal cars, feel wrecked, play it cool, longing for real love and true freedom. Startlingly raw and deeply moving, While We Were Dreaming is an extraordinary coming of age novel by one of Germany's most ambitious writers, full of passion, rage, hope and despair.

"The cumulative power of the well-constructed, pitiless and unflinching dispatches from the underbelly of society is remarkable. Historical events often pass unnoticed by those living through them, unaware even of how much their lives have been changed. It is Meyer’s achievement to capture the profound effects those events had on the lives of those at the bottom of German society." — David Mills, Sunday Times

"A book like a fist. German literature has not seen such a debut for a long time, a book full of rage, sadness, pathos and superstition. —Felicitas von Lovenberg, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

"Clemens Meyer’s great art of describing people takes the form of the Russian doll principle: a story within a story within a story. So much is so artfully interwoven that his work breaks the mould of the closed narrative." —Katharina Teutsch, Die Zeit

>>Read an extract.

>>Other books long-listed for the 2023 International Booker Prize.

We think we know the trench coat, but where does it come from and where will it take us? From its origins in the trenches of WW1, this military outerwear came to project the inner-being of detectives, writers, reporters, rebels, artists and intellectuals. The coat outfitted imaginative leaps into the unknown. Trench Coat tells the story of seductive entanglements with technology, time, law, politics, trust and trespass. Readers follow the rise of a sartorial archetype through media, design, literature, cinema and fashion. Today, as a staple in stories of future life-worlds, the trench coat warns of disturbances to come.

>>Other books in the 'Object Lessons' series.

In the wake of an insignificant battle between two long-forgotten kingdoms in fourteenth-century southern India, a nine-year-old girl has a divine encounter that will change the course of history. After witnessing the death of her mother, the grief-stricken Pampa Kampana becomes a vessel for the goddess Parvati, who begins to speak out of the girl's mouth. Granting her powers beyond Pampa Kampana's comprehension, the goddess tells her that she will be instrumental in the rise of a great city called Bisnaga - literally 'victory city' - the wonder of the world. Over the next two hundred and fifty years, Pampa Kampana's life becomes deeply interwoven with Bisnaga's, from its literal sowing out of a bag of magic seeds to its tragic ruination in the most human of ways: the hubris of those in power. Whispering Bisnaga and its citizens into existence, Pampa Kampana attempts to make good on the task that Parvati set for her: to give women equal agency in a patriarchal world. But all stories have a way of getting away from their creator, and Bisnaga is no exception. As years pass, rulers come and go, battles are won and lost, and allegiances shift, the very fabric of Bisnaga becomes an ever more complex tapestry - with Pampa Kampana at its center.

| {STELLA} | >> Read all Stella's reviews. |

|

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

Tropisms by Nathalie Sarraute (translated by Maria Jolas) {Reviewed by THOMAS} In biology, the directional response of a plant’s growth either towards or away from an external stimulus that either benefits or harms it is termed tropism. Nathalie Sarraute, in this subtly astounding book, first published in 1939, applies the term to her brief studies of ways in which humans are affected by other humans beneath the level of cognitive thought. In these twenty-four pieces she is interested in describing “certain inner ‘movements’, which are hidden under the commonplace, harmless appearances of every instant of our lives. These movements, of which we are hardly cognisant, slip through us on the frontiers of consciousness, in the form of undefinable, extremely rapid sensations. They hide behind our gestures, beneath the words we speak. They constitute the secret source of our existence.” We are either attracted or repulsed by the presence of others, though attraction and repulsion are indistinguishable at least in the degree of connection they effect, we are either benefitted or harmed by others, or both at once, but we cannot act upon or even acknowledge our impulses without making intolerable the life we have striven so hard to make tolerable in order to survive. Neurosis may be a sub-optimal functional mode, but it is a functional mode all the same. We wish to destroy but we fear, rightly, being also destroyed. We sublimate that which would overwhelm us, preferring inaction to action for fear of the reaction that action would attract, but we cannot be cognisant of the extent to which this process forms the basis of our existence for such awareness would be intolerable. We must deceive ourselves if we are to make the intolerable tolerable, and we must not be aware that we so deceive ourselves. Such devices as character and plot, which we both apply to ‘real life’ and practise in the reading and writing of novels, are “nothing but a conventional code that we apply to life” to make it liveable. Sarraute’s brilliance in this book, which is the key to her other novels, and which constitutes an object lesson for any writer, is to observe and convey the impulses “constantly emerging up to the surface of the appearances that both conceal and reveal them.” Subliminal both in its observations and in its effects, the book suggests the urges and responses that form the understructure of relationships, unseen beneath the effectively compulsive conventions, expectations and obligations that comprise our conscious quotidian lives. Many of the pieces suggest how children are subsumed, overwhelmed and harmed by adults: “They had always known how to possess him entirely, without leaving him an inch of breathing space, without a moment’s respite, how to devour him down to the last crumb.” Sarraute is not interested here in character or plot, but in the unacknowledged impulses and responses that underlie our habits, attitudes and actions. Each thing emerges from, or tends towards, its opposite. All that is beautiful moves towards the hideous. Against what is hideous, something inextinguishable moves to rebel, to survive. ‘Tropism’ also suggests the word ‘trop’ in French, in the sense of ‘too much’. The ideas we have of ourselves are flotsam on surging unconscious depths in which there is no individuality, only impulse and response. Sarraute’s tropisms give insight into the patterns, or clustering tendencies, of these impulses and responses, and are written in remarkable, beautiful sentences. “And he sensed, percolating from the kitchen, squalid human thought, shuffling, shuffling in one spot, going round and round, in circles, as if they were dizzy but couldn’t stop, as if they were nauseated but couldn’t stop, the way we bite our nails, the way we tear off dead skin when we’re peeling, the way we scratch ourselves when we have hives, the way we toss in our beds when we can’t sleep, to give ourselves pleasure and to make ourselves suffer, until we are exhausted, until we’ve taken our breath away.” |

>>A host of new friends.

>>The joy of growing things.

>>Read an extract.

>>Compost and nasturtiums.

>>Rootbound.

>>Other books on gardening.

>>Your copy of Why Women Grow.

NEW RELEASES

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

Marianne Dubuc’s children’s books are delightful: wonderful stories, excellent characters, humour as well as heart; and charming illustrations, where there is always more to find on the page. You may already have The Lion and the Bird on your shelf, or gifted the excellent 'Mr Postmouse' titles. Up the Mountain is another to add to your or a child’s collection. Mrs Badger every Sunday heads outdoors and walks up the mountain. She loves walking through the fields, past the apple trees, across the streams and climbing higher and higher. To get to the top, to see the world, is for her the best place to be. On the way, she greets her friends — various animals that live on the mountain and in the trees. One day, a shy cat, Leo, is watching her. Leo thinks he is too small to climb the mountain, but, with some encouragement and help from Mrs Badger (and a few rests along the way) and a dose of curiosity about what’s at the top, he makes it. After that, every Sunday Leo joins his friend Mrs Badger, and they enjoy the wonders of the mountain, both the journey and the destination. As the days go by, Mrs Badger is the one who needs the rest and encouragement, until one day it’s just Leo venturing out and then returning to Mrs Badger’s house with stories and treasures. Eventually, Mrs Badger’s mountain becomes Leo’s mountain and the cycle of discovery and wonder continues. This is a charming story about friendship, and aging; about sharing and curiosity — a story of looking out at the world with wonder and care. This edition is translated and published by the excellent children’s press Book Island. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

In the Dark Room by Brian Dillon {Reviewed by THOMAS} Unless we are wrested by a pervasive trauma from the entire set of circumstances which constitute our identities, which are always contextual rather than intrinsic, our memories are never kept solely within the urns of our minds, so to call them, but are frequently prodded, stimulated and remade by elements beyond ourselves, or, indeed, are outsourced to these elements. Brian Dillon’s In the Dark Room is thoughtful examination of the way in which his memories of his parents, who both died as he was making the transition into adulthood, are enacted through the interplay of interior and exterior elements (the book is divided into sections: ‘House’, ‘Things’, ‘Photographs’, ‘Bodies’, ‘Places’). It is the physical world, rather than time, that is the armature of memory: time, or at least our experience of it, is contained in space, is, for us, an aspect of space, of physical extension, of objects. It is through objects that the past reaches forward and grasps at the present. And it is through the dialogue with objects that we call memory that these objects lose their autonomy and become mementoes, bearers of knowledge on our behalf or in our stead. Memory both provides access to and enacts our exclusion from the spaces of the past to which it is bound. In many ways, when the relationship between the object and the memory seem closest, this relationship is most fraught. Photographs, which Dillon describes as “a membrane between ourselves and the world,” are not so much representations as obscurations of their subjects. The subjects of photographs both inhabit an immediate moment and are secured by them in the “debilitating distance” of an uninhabitable past. When Dillon is looking at a photograph of his mother, “the feeling that she was manifestly present but just out of reach was distinctly painful. … Photography and the proximity of death tear the face from its home and memory and set it adrift in time.” All photographs (and, indeed, all associative objects) are moments removed from time and so are equivalents, contesting with interior memories to be definitive. Photographs, even more than other objects, but other objects also, are mechanisms of avoidance and substitution as much as they are mechanisms of preservation. Memory, illness, death all distort our experience of time, but so does actual experience, and it is this distortion that generates memory, that imprints the physical with experience “spreading itself everywhere like a disease of the retina” (in the words of George Eliot). Intense experience, especially traumatic experience, death, illness, loss, violence, occlude the normal functions of memory and push us towards the edges of consciousness, touching oblivion as they also imprison us in the actual. As Dillon found, if experience cannot be experienced all at once, the context of the experience can bear us through, but it must be revisited in memory, repeatedly, until the experience is complete, if this is ever possible. Memory will often co-opt elements of surroundings to complete itself, and, especially if associative objects are not present, it will magnify its trauma upon unfamiliar contexts, increasing the separation and isolation it also seeks to overcome. Must the past be faced as directly as possible so that we may at last turn away from it? >>Brian Dillon's new book, Affinities, is available now |

Book of the Week: Always Italicise: How to write while colonised by Alice Te Punga Somerville

"Always italicise foreign words," a friend of the author was advised. In her first book of poetry, Māori scholar and poet Alice Te Punga Somerville does just that. In wit and anger, sadness and aroha, she reflects on how to write in English as a Māori writer, and how to trace links between Aotearoa and wider Pacific, Indigenous and colonial worlds.

>>Always Italicise has been short-listed for the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the 2023 Ockham New Zealand Book awards.

>>Writing while colonised.

>>English has broken my heart.

>>English has broken my heart on the radio.

>>Two Hundred and Fifty Ways to Start an Essay About Captain Cook.

>>Our stories about Cook.

>>(Not quite) 250 ways.

>>250 ways.

>>Writing the new world.

>>Interconnections.

>>Te Punga Somerville wrote a standout essay in Ngā Kete Mātauranga.

>>Environment and identity.

>>Challenging stories.

>>A bibliography of writing by Māori in English.

>>Your copy of Always Italicise.

We will be giving away a copy of the remarkable Renters United! / Lawrence & Gibson Publishing tabloid-format! illustrated! edition of Murdoch Stephens's biting and hilarious RAT KING LANDLORD with every book order we dispatch (until supplies are exhausted). And if you order a Lawrence & Gibson book we will put in a bonus copy!

>>Read Stella's review of RKL.

>>Books from L&G.

JANN MEDLICOTT ACORN PRIZE FOR FICTION

Better the Blood

Michael Bennett (Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Whakaue)

(Simon & Schuster)Kāwai: For Such a Time as This

Monty Soutar (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, Ngāti Kahungunu)

Mrs Jewell and the Wreck of the General Grant

Cristina Sanders

The Cuba PressBased on the true story of an 1866 shipwreck, this re-telling of the endurance of the survivors on a sub-Antarctic island is impeccably researched and peopled by rounded, realistic and complex characters. Dramatic and well paced, it is rich with vivid descriptions of sea, land and weather, and Cristina Sanders offers insight into the physical and psychological effects of being stranded in an inhospitable environment. Historical fiction at its best.

>>Your copy.

MARY AND PETER BIGGS AWARD FOR POETRY

Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised

Alice Te Punga Somerville (Te Āti Awa, Taranaki)

Auckland University PressAlice Te Punga Somerville’s meticulously crafted collection resonates with aroha, wit, sadness and anger. Advice to “italicise all of the foreign words in her poems” becomes a catalyst to exploring the dynamics of racism, colonisation, and writing in English as a Māori writer. Poems float like gourds strung with musings and personal recounts. English words incline as foreign words, but te reo syllables evade linguistic ambushes, camouflaged soundscapes and erasure. They stand upright, mark Space-Time like pou.

>>Your copy.People Person

Joanna Cho

Te Herenga Waka University PressJoanna Cho explores relationships, identity and survival with an aching, ironic honesty. A people person may have a name bought from a fortune-teller, drive battered cars, light up rooms with their hearts, or miss the smell of kawakawa ointment. Cho navigates expectations and choices in imagined and recalled stories, skilfully connecting folklore with autobiographical snapshots from South Korea and Aotearoa. Whimsical, surreal, magical and mundane elements meld and clash in poetic vignettes.

>>Your copy.Sedition

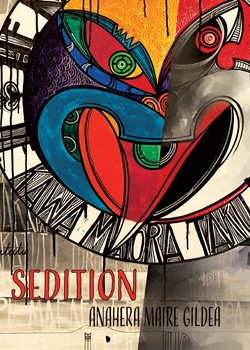

Anahera Maire Gildea (Ngāti Tukorehe)

Taraheke | Bush LawyerSedition flows through generations of dis-ease, enlivens tongues stilled by loss and trauma, excavates a genealogy of resistance. It’s a contemplative, defiant collection that resists the commodification of culture and whenua, and the ongoing perversity of neo-colonialism. Poems float upon the notion that we walk into the future facing our past, which embodies and shapes us. Anahera Maire Gildea agitates, untangles and reweaves threads of outrage, dystopia and anguish as she resolutely redraws detrimental power.

>>Your copy.We’re All Made of Lightning

Khadro Mohamed

We Are Babies Press, Tender PressKhadro Mohamed’s elegiac collection features a speaker torn between multiple worlds. Pendulating from prose to lyric, it is a ghostly work in which dreams and memory bleed into each other, as do its places: Egypt, Somalia, Newtown and Kilbirnie. Even time becomes concurrent, and for Mohamed, the past is right there in the present. In this collision of languages and worlds, the possibility and impossibility of home is both grieved and celebrated.

>>Your copy.

BOOKSELLERS AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND AWARD FOR ILLUSTRATED NON-FICTION

Jumping Sundays: The Rise and Fall of the Counterculture in Aoteroa New Zealand

Nick Bollinger

Auckland University PressWith its distinctive cover, bold typography and risograph hues on uncoated stock, this book demands to be read from page one. Weaving original sources into an engaging narrative, Nick Bollinger has crafted a considered and fitting history. Photographs from private collections add to its rich production, balancing text and illustration in ways that belie its size. Like the period it surveys, Jumping Sundays is a game-changer.

>>Your copy.Robin White: Something is Happening Here

Edited by Sarah Farrar, Jill Trevelyan and Nina TongaTe Papa Press and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o TāmakiThis is more than an exhibition turned art book. Stunning reproductions, historical essays and the insights of two dozen contributors do justice to the institution that is Robin White. As iconic screenprints flow seamlessly into large format barkcloth, White’s border-crossing practice is temporally divided with the savvy use of typographic spreads. Space, too, is given to the voices of her Kiribati, Fijian and Tongan collaborators. Strikingly elegant yet comprehensive, excellence is what’s happening here.

>>Your copy.Secrets of the Sea: The Story of New Zealand’s Native Sea Creatures

Robert Vennell

HarperCollinsSecrets of the Sea is a treasury of interesting facts, beautiful photography and remarkable prose. Beyond the luscious illustrations is a perfect blend of science, history and mātauranga Māori that gives the text depth and relevance and reveals in fascinating (and urgent) ways the interconnectedness of the human and extra human world. Visually compelling and hugely accessible, this impactful book will delight the marine biologist, sea aficionado and general reader alike.

>>Your copy.Te Motunui Epa

Rachel Buchanan (Taranaki, Te Ātiawa)

Bridget Williams BooksInnovative and immensely topical, Te Motunui Epa is a triumph of storytelling and a challenge to the confines of traditional historiography. Rachel Buchanan’s meticulous research and compelling writing is complemented by the very best in graphic design – from its light-catching cover to the black-bordered array of archival documents. Generous while unafraid to confront the colonial hurt at the heart of the story, this is a deceptively powerful and enduring work.

>>Your copy.

GENERAL NON-FICTION AWARD

A Fire in the Belly of Hineāmaru: A Collection of Narratives about Te Tai Tokerau Tūpuna

Melinda Webber (Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Hau, Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whakaue) and Te Kapua O’Connor (Ngāti Kurī, Pohūtiare)

Auckland University PressAn exquisite and innovative book that uses a form of storytelling, pūrākau, to construct further stories that elucidate and challenge. It adds a layer of narrative truth to what we know about Te Tai Tokerau and, more importantly, shifts existing perceptions. It reveals the richness of knowledge in whakapapa which, especially for Te Tai Tokerau rangatahi, will spark significant personal and collective inspiration.

>>Your copy.Downfall: The Destruction of Charles Mackay

Paul Diamond (Ngāti Hauā, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi)

Massey University PressThis beautifully produced and generous book is a fascinating account of an extraordinary moment in small-town colonial New Zealand with its vivid line-up of characters, a revenge plot, blackmail and local Pākehā political intrigue. Alongside gripping, skilled and elegant popular historical storytelling, readers will find well-researched and closely observed insights into aspects of our national character, and our struggles with social decency.

>>Your copy.Grand: Becoming my Mother’s Daughter

Noelle McCarthy

Penguin Random HouseThis memoir presents both a woman confronting her own shame and the shame of generations with visceral honesty. It offers a treatise on forgiveness and a light of hope. Noelle McCarthy’s command of language imbues readers with sight, sound, smell and taste. It is complete as an individual narrative, while the centrality of the mother-daughter relationship and the weight that loads onto the process of knowing oneself offers much to our collective emotional intelligence.

>>Your copy.The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi

Ned Fletcher

Bridget Williams BooksNed Fletcher’s extensively researched and meticulously constructed book provides a valuable contribution to scholarship, history and law, and makes a timely and evolved interjection into the conversations of this country. Readers are led to evidenced conclusions via Fletcher’s clear hypotheses, structural commitment to reason and thorough examination of the characters and context involved in the creation of the English text of Aotearoa’s founding document.

>>Your copy.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

I’m re-reading Rat King Landlord in tabloid format complete with illustrations — it’s the Renters United! edition. Bravo, publishers Lawrence & Gibson! We are giving away a copy with every book order. Here’s my review of the paperback edition (2020): Ever wanted a crash course in Marxist theory, class structure, exploitation and capitalist advantage through property ownership, but found the reading a little too onerous? Well, then this novel is for you. Rat King Landlord, newly out of the excellent Lawrence & Gibson stable from the pen of Murdoch Stephens, is a satire that places you squarely in the continuing saga of our housing crisis — specifically the rental dilemma. Looked for a flat in Wellington lately; lived in an overpriced damp and mouldy house with strange flatmates and yet stranger landlord? — you need to look no further than here for a slice of almost-truth. Meet our flatmate, getting up early to make coffee in his haze of infatuation for Freddie, before she heads to work at the hip Broviet Brunion cafe located at the edgy end of the city, while flattie number three, Caleb, sleeps on, or whatever else he does, behind his closed door. So typical flatting life? Think again! Everyone wants to get on the property ladder, including the rats. Maligned and misunderstood, the rats are taking back the yard and the house. They are no longer content to live off your scraps while avoiding your traps. Rats have rights too! At the same time, strange posters are popping up all over the city advertising an event unlike any other — The Night of the Smooth Stones. Unauthorised and taking over billboard space owned by a corporate in cahots with the council, the posters resist being painted over or torn down. The message is oblique and the word on the street — well, on social media and in the huddled conversations of the politically leveraged hipsters — is that a revolution is about to hit the streets. Targets: property agents (loud hiss), landlords (hiss) and house owners (half-hearted small hiss). While the street is heating up, at home the temperature is rising too. The human landlord has died falling off a shonky ladder and his will results in the ownership of the house ending up in the hands (paws) of the Rat — the last being to witness him alive. Don’t even think about being animalist. As the Rat adjusts to his newfound status, learning English through texting (specifically with Caleb — the reclusive — who has an odd fascination with his Rat associate and an employer/employee relationship in due course — one that favours him over his flatmates), upgrading his shed, and making a slippery agreement to get himself into the house as a flatmate/landlord (alarm bells!), our protagonist becomes more agitated by the situation. Fire in the backyard, vigilantes on the street, pseudo-rebellion in the streets — who’s a landlord and who’s a renter? Have you got proof of your status or lack of? And the nights of rebellion just keep getting stranger. Who's behind the call to arms, and why is Freddie's boss acting weird? Rat King Landlord is a hilarious trip with a serious underbelly. |