A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #358th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending, find out which book won the 2023 Booker Prize — and get your seasonal gift-choosing done!

1 December 2023

A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #358th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending, find out which book won the 2023 Booker Prize — and get your seasonal gift-choosing done!

1 December 2023

In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova (translated from Russian by Sasha Dugdale)

The past gets bigger every day, he realised, every day the past gets a day bigger, but the present never gets any bigger, if it has a size at all it stays the same size, every day the present is more overwhelmed by the past, every moment in fact the present more overwhelmed by the past. Perhaps that should be longer rather than bigger, he thought, same difference, he thought, not making sense but you know what I mean, he thought, the present has no duration but the duration of the past swells with every moment, pushing at us, pushing us forward. Anything that exists is opposed by the fact of its existing to anything that might take its existence away, he wrote, the past is determined to go on existing but it can only do this by hijacking the present, he wrote, by casting itself forward and co-opting the present, or trying to, by clutching at us with objects or images or associations or impressions or with what we could call stories, wordstuff, whatever, harpooning us who live only in the present with what we might call memory, the desperation, so to call it, of that which no longer exists except to whatever degree it attaches itself to us now, the desperation to be remembered, to persist, even long after it has gone. Memory is not something we achieve, he wrote, memory is something that is achieved upon us by the past, by something desperate to exist and go on existing, by something carrying us onwards, if there is such a thing as onwards, something long gone, dead moments, ghosts preserving their agency through objects, images, words, impressions, associations, all that, he wrote, coming to the end of his thought. This book, he thought, Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory, is not really about memory at all in the way we usually understand it, it is not about the way an author might go around recalling experiences she had at some previous point in her life, this book is about the way the past forces itself upon us, the way the past forces itself upon us particularly along the channels of family, of ancestry, of blood, so to call it, pushing us before it in such as way that we cannot say if our participation in this process is in accordance with our will or against it, the distinction in any case makes no sense, he thought, there is only the imperative of all particulars not so much to go on existing, despite what I said earlier, though this is certainly the effect, as to oppose, by the very fact of their particularity, any circumstance that would take that existence away. Everything opposes its own extinction, he thought, even me. That again. But the past is vulnerable, too, which is why memory is desperate, a clutching, the past depends upon us to bear its particularity, and we have become adept at fending it off, at replacing it with the stories we tell ourselves about it. The stories we tell about the past are the way we keep the past at bay, the way we keep ourselves from being overwhelmed by this swelling urgent unrelenting past. “There is too much past, and everyone knows it,” writes Stepanova, “The excess oppresses, the force of the surge crashes against the bulwark of any amount of consciousness, it is beyond control and beyond description. So it is driven between banks, simplified, straightened out, chased still-living into the channels of narrative.” When Stepanova’s aunt dies she inherits an apartment full of objects, photographs, letters, journals, documents, and she sets about defusing the awkwardness of this archive’s demands upon her through the application of the tool with which she has proficiency, her writing. Although she writes the stories of her various ancestors and of her various ancestors’ various descendants, she is aware that “this book about my family is not about my family at all, but about something quite different: the way memory works, and what memory wants from me.” Stepanova’s family is unremarkable from a historical point of view, Russian Jews to whom nothing particularly traumatic happened, notwithstanding the possibilities during the twentieth century for all manner of traumatic things to happen to those such as them, and they were not marked out for fame or glory, either, whatever that means, in any case they had no wish to be noticed. History is composed mainly of ordinariness, the non-dramatic predominates, he thought, although there may be notable crises pressing on these particular people, Stepanova’s family for example but the same is true for most people, these notable crises do not actually happen to these particular people. Do not equals did not. The past, as the present, he wrote, was undoubtedly mundane for most people most of the time, and yet they still went on existing, at least resisting their extinction in the most banal of fashions. Is this conveyed in history, though, family or otherwise, he wondered, how does the repetitive uneventfulness of everyday life in the past press upon the present, if at all? Can we appreciate any particularity in the mundanity of the past, he wondered, are we not like the tiny porcelain dolls, the ‘Frozen Charlottes’ that Stepanova collects, produced in vast numbers, flushed out into the world, identical and unremarkable except where the damage caused by their individual histories imbues them with particularity, with character? “Trauma makes us individuals—singly and unambiguously—from the mass product,” Stepanova writes. Who would we be without hardship, if indeed we could be said to be? No idea, not that this was anyway a question for which he had anticipated an answer, he thought. “Memory works on behalf of separation,” Stepanova writes. “It prepares for the break without which the self cannot emerge.” Memory is an exercise of edges, he thought, and all we have are edges, the centre has no shape, there is only empty space. He thought of Alexander Sokurov’s film Russian Ark, and thought how it too piled detail upon detail to reduce the transmission—or to prevent the formation—of ideas about the past, the past piles more and more information upon us in the present, occluding itself in detail, veiling itself, reducing both our understanding and our ability to understand. Stepanova’s words pile up, her metaphors pile up, her sentences pile up, her words ostensibly offer meaning but actually withhold it, or ration it. Although In Memory of Memory is in most ways nothing like Russian Ark, he thought, why did he start this comparison, as with Russian Ark, In Memory of Memory is—entirely appropriately—both fascinating and boring, both too long and never quite reaching a point of satisfaction, the characters both recognisable and uncertain but in any case torn away, at least from us, the actions both deliberate and without any clear rationale or consequence—just like history itself. No residue. No thoughts. No realisations. No salient facts. No wisdom. The past drives us onward, pushes us outward as it inflates.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

Prophet Song is furious in tempo and content. It has knocked me sideways and taken all the other contenders off my best book of the year (and it’s been a year of very good fiction) list by strides. From the knock on the door to the final moment, this novel is breathless, heart-wrenching and brutal. So human, so foreign, yet so real. Eilish is a mother, a wife, a daughter, someone’s sister. She is a microbiologist/desk bound researcher, harrying her children into the car to get to school on time, coaxing her husband, school teacher/union delegate for an answer to a question when he is miles away in his own thoughts, and wondering what her teenage son sees in that girl. She could be your neighbour. Set in an alternative Ireland, nationalism is on the rise. Larry is warned to call off the strike. People are wearing party pins on their lapels. The police are knocking on the door. And then…Larry is arrested. Lawyers can’t make contact with their clients. People are leaving the country. Flags are flying from homes in the street and if you don’t have one, you're against them. You’re a traitor. And then…the rebellion begins and you are at war. Your father’s mind is slipping, your eldest son needs to leave the country, your husband has disappeared, your daughter won’t eat and your baby is teething, while your 12 year-old has become an enigma. And then… food is scarce, bombs are falling, sometimes the electricity comes back on and you bake bread and do the washing on the fast cycle. Prophet Song is an urgent critique on brutality and power; and what it takes to remain in the world even when you are disorientated and disconnected from everything you know and that which holds you safe. The language is bundled together, the sentences almost stepping on each other, as claustrophobic as the situation Eilish finds herself in. This is a brilliant novel that needs to be read for its beauty of language and structure, as well as its haunting content.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch is the winner of the 2023 Booker Prize. Here’s why, according to Esi Edugyan, Chair of the judges: “From that first knock at the door, Prophet Song, forces us out of our complacency as we follow the terrifying plight of a woman seeking to protect her family in an Ireland descending into totalitarianism. We felt unsettled from the start, submerged in – and haunted by – the sustained claustrophobia of Lynch’s powerfully constructed world. He flinches from nothing, depicting the reality of state violence and displacement and offering no easy consolations. Here the sentence is stretched to its limits – Lynch pulls off feats of language that are stunning to witness. He has the heart of a poet, using repetition and recurring motifs to create a visceral reading experience. This is a triumph of emotional storytelling, bracing and brave. With great vividness, Prophet Song captures the social and political anxieties of our current moment. Readers will find it soul-shattering and true, and will not soon forget its warnings.’”

Use our website to choose your seasonal gifts (and books for yourself as well)!

A new book is a promise of good times ahead. Click through for your copies:

Selected Poems by Geoff Cochrane $40

”Geoff Cochrane's is a whole world, rendered in lines at once compressed and open, mysterious and approachable.” —Damien Wilkins

”Over the years, Cochrane's work has been a joy to me, a solace, a proof that art can be made in New Zealand which shows ourselves in new ways.” —Pip Adam

”Would he break your heart, make you chuckle or tear you a new one – one never quite knew. He had this way of creating a moment of meeting that elided everything else, a calm where all our antennae raised as one and you never knew what would come out of his mouth, or his work. —Carl Shuker

(Hardback)

Why Memory Matters: ‘Remembered histories’ and the politics of the past by Rowan Light $18

”Behind the foreground narratives of justification, real or symbolic wounds are stored in the archives of cultural memory.” From curriculum to commemoration to constitutional reform, our society is in the grip of memory, a politics and culture marked by waves of loss, grief, absence and victimhood. Why are certain aspects of the past remembered over others, and why does this matter? In response to this fraught question, historian Rowan Light offers a series of case studies about local debates about history in New Zealand. These provisional judgements of the past illuminate aspects of what it means to remember — and why it matters. (Paperback)

The Forest Brims Over by Maru Ayase (translated from Japanese by Haydn Trowell) $37

Nowatari Rui has long been the subject of her husband's novels, her privacy and identity continually stripped away, and she has come to be seen by society first and foremost as the inspiration for her husband's art. When a decade's worth of frustrations reaches its boiling point, Rui consumes a bowl of seeds, and buds and roots begin to sprout all over her body. Instead of taking her to a hospital, her husband keeps her in an aquaterrarium, set to compose a new novel based on this unsettling experience. But Rui breaks away from her husband by growing into a forest — and in time, she takes over the entire city. (Paperback)

”The effectiveness of The Forest Brims Over lies precisely in Ayase's thorough awareness of the power of fiction: While we may never grow forests out of our bodies, Ayase has enabled us to experience in her words how doing so might just change society for the brighter." —Eric Margolis, The Japan Times

Birdspeak by Arihia Latham $25

”Let me speak as if a bird

Let me speak of you in our reo as if

your memories have wings”

“A call to and from the wild. It is a call for peace and a call to fight. Latham writes from the mud and moonlight; the caves, craters, and lakes of te taiao. Like the digging bird she uses her pen to claw memories out of the earth—the mundane, the joyful, the worried, the violent, the aching memories—before rinsing them in the awa and holding them up, to make us wonder whose they are; hers or ours.” —Becky Manawatu

”There's so much whakapapa to this book with the ancestors, Arihia’s wha nau, the deep pūrākau in it, and all the kaitiaki manu that fly through the pages. Every poem feels like a karanga, or an oriori, or a patere, or even a spell. Reading my tīpuna in her words feels like coming home.” —Ruby Solly

(Paperback)

From Paper to Platform: How tech giants are redefining news and democracy by Merja Myllylahti $18

While global regulators grapple with tech behemoths such as Google and Facebook through evolving laws and regulations, the New Zealand government has held a laissez-faire stance. In From Paper to Platform, prominent New Zealand media scholar, Merja Myllylahti, scrutinises how major digital platforms exert ever-growing influence over news, journalism, our everyday lives, personal rights and access to information. This analysis provides not only insights into the relentless and pervasive impacts these platforms have on our daily experiences, but also delves into their effects on societal structures and the potential perils for our democratic future. (Paperback)

Landfall 246 edited by Lynley Edmeades $30

Presents the winners of the 2023 Landfall Essay Competition; the 2023 Kathleen Grattan Poetry Award ; and the 2023 Caselberg Trust International Poetry Prize. Art: Steven Junil Park, Ann Shelton and Wayne Youle; Non-fiction: Aimee-Jane Anderson-O'Connor, Madeleine Fenn, Eliana Gray and Bronwyn Polaschek; Poetry: Jessica Arcus, Tony Beyer, Victor Billot, Cindy Botha, Danny Bultitude, Marisa Cappetta, Medb Charleton, Janet Charman, Cadence Chung, Brett Cross, Mark Edgecombe, David Eggleton, Rachel Faleatua, Holly Fletcher, Jordan Hamel, Bronte Heron, Gail Ingram, Lynn Jenner, Erik Kennedy, Megan Kitching, Jessica Le Bas, Therese Lloyd, Mary Macpherson, Carolyn McCurdie, Kirstie McKinnon, Frankie McMillan, Pam Morrison, Jilly O'Brien, Jenny Powell, Reihana Robinson, Tim Saunders, Tessa Sinclair Scott, Mackenzie Smith, Elizabeth Smither, Robert Sullivan, Catherine Trundle, Sophia Wilson, Marjory Woodfield, Phoebe Wright; Fiction: Pip Adam, Rebecca Ball, Lucinda Birch, Bret Dukes, Zoë Meager, Petra Nyman, Vincent O'Sullivan, Rebecca Reader, Pip Robertson, Anna Scaife, Kathryn van Beek and Christopher Yee; reviews. (Paperback)

Arita / Table of Contents: Studies in Japanese porcelain by Annina Koivu $110

A beautiful and fascinating large-format book. The art of Japanese porcelain manufacturing began in Arita in 1616. Now, on its 400th anniversary, Arita / Table of Contents charts the unique collaboration between 16 contemporary designers and 10 traditional Japanese potteries as they work to produce 16 highly original, innovative and contemporary ceramic collections rooted in the daily lives of the 21st century. More than 500 illustrations provide a fascinating introduction to the craft and region, while the contemporary collections reveal the unique creative potential of linking ancient and modern masters. (Hardback)

The Things We Live With: Essays on uncertainty by Gemma Nisbet $37

After her father dies of cancer, Gemma Nisbet is inundated with keepsakes connected to his life by family and friends. As she becomes attuned to the ways certain items can evoke specific memories or moments, she begins to ask questions about the relationships between objects and people. Why is it so difficult to discard some artefacts and not others? Does the power exerted by precious things influence the ways we remember the past and perceive the future? As Nisbet considers her father's life and begins to connect his experiences of mental illness with her own, she wonders whether hanging on to 'stuff' is ultimately a source of comfort or concern. The Things We Live With is a collection of essays about how we learn to live with the 'things' handed down in families which we carry throughout our lives — not only material objects, but also grief, memory, anxiety and depression. It's about notions of home and restlessness, inheritance and belonging — and, above all, the ways we tell our stories to ourselves and other people. (Paperback)

A Guided Discovery of Gardening: Knowledge, creativity and joy unearthed by Julia Atkinson-Dunn $50

For some, gardening is a mysterious activity involving muck, unfathomable know-how and physical labour. To others, it is a gateway to creativity, well-being and magic. Julia Atkinson-Dunn knows what it is to stand on both sides of this fence and has channeled her discovery of gardening into a book to aid and inspire others in their own. A Guided Discovery of Gardening is a comprehensive partner in creating a garden, arranged to sweep beginner and progressing gardeners through informative basics to fascinating insights laid bare through Julia's casual, friendly and often personal writing. From introductions to plant types and taking cuttings to valuable tips for home buyers and the curation of seasonally responsive planting. Particularly relevant to temperate regions around the world, rich doses of handy knowledge are intermingled with reflective essays and visual visits to some of her favourite New Zealand gardens, as well as her own. (Flexibound)

Begin Again: The story of how we got here and where we might go — Our human story, so far by Oliver Jeffers $33

Oliver Jeffers shares a history of humanity and his dreams for its future. Where are we going? With his bold, exquisite artwork, Oliver Jeffers starts at the dawn of humankind following people on their journey from then until now, and then offers the reader a challenge: where do we go from here? How can we think about the future of the human race more than our individual lives? How can we save ourselves? How can we change our story? (Hardback)

Roman Stories by Jhumpa Lahiri $40

A man recalls a summer party that awakens an alternative version of himself. A couple haunted by a tragic loss return to seek consolation. An outsider family is pushed out of the block in which they hoped to settle. A set of steps in a Roman neighbourhood connects the daily lives of the city's myriad inhabitants. This is an evocative fresco of Rome, the most alluring character of all: contradictory, in constant transformation and a home to those who know they can't fully belong but choose it anyway. (Paperback)

Open Up by Thomas Morris $33

Five achingly tender, innovative and dazzling stories of (dis)connection. From a child attending his first football match, buoyed by secret magic, and a wincingly humane portrait of adolescence, to the perplexity of grief and loss through the eyes of a seahorse, Thomas Morris seeks to find grace, hope and benevolence in the churning tumult of self-discovery. (Paperback)

”Heart-hurtingly acute, laugh-out-loud funny, and one of the most satisfying collections I've read for years.'“ —Ali Smith

”This brilliant, funny, unsettling book is a work of deep psychological realism and a philosophical inquiry at the same time. Thomas Morris is a master of the contemporary short story, and the stories in this collection are his best.” —Sally Rooney

”That tonic gift, the sense of truth — the sense of transparency that permits us to see imaginary lives more clearly than we see our own. The tonic comes in large doses in Thomas Morris's short-story collection.” —Irish Times

Night Tribe by Peter Butler $25

Twelve-year-old Toby and his sister Millie, fourteen, are tramping the Heaphy Track with their mother when they go off-track to find an old surveyor’s hut their grandfather used. When their mother breaks her leg in a hidden hole the kids set off back to fetch help. They spend some nights alone, hungry and lost. So far, so ordinary, but there is something strange about the cave they’ve camped next to. A little woman emerges and draws them in with the promise of food and shelter. They enter an underground cavern that is deeper than they first thought and where a whole tribe lives. These people believe in natural law, not human law, and have deliberately hidden away from humans believing that here they can survive a total war or pandemic. The kids are intrigued by the techniques this strange people have used to survive but this is tempered by the growing realisation that the Tribe don’t want them to leave. (Paperback)

Here is Hare by Laura Shallcrass $23

An appealing peek-a-book board book with animal characters. (Board book)

Juno Loves Legs by Karl Geary $37

Juno loves Legs. She's loved him since their first encounter at school in Dublin, where she fought the playground bullies for him. He feels brave with her, she feels safe with him, and together they feel invincible, even if the world has other ideas. Driven by defiance and an instinctive feeling for the truth of things, the two find their way from the backstreets and city pubs to its underground parties and squats. Here, on the verge of adulthood, they reach a haven of sorts, a breathing space to begin their real lives. Only Legs's might be taking him somewhere Juno can't follow. Set during the political and social unrest of the 1980s, as families struggled to survive and their children struggled to be free, this beautiful, vivid novel of childhood friendship is about being young, being hurt, being seen and, most of all, being loved. (Paperback)

”Juno Loves Legs will haunt you long after you have read it. In gorgeous, effortless prose, Karl Geary bears witness to those who, like his protagonists, are invisible and voiceless. By boldly confronting the darkness, this novel finds the light.” —Gabriel Byrne

Listen: On music, sound, and us by Michel Faber $40

What is going on inside us when we listen? Michel Faber explores two big questions: how we listen to music and why we listen to music. To answer these he considers biology, age, illness, the notion of 'cool', commerce, the dichotomy between 'good' and 'bad' taste and, through extensive interviews with musicians, unlocks some surprising answers. (Paperback)

Lawrence of Arabia: An in-depth glance at the life of a twentieth-century legend by Ranulph Fiennes $42

Co-opted by the British military, archaeologist and adventurer Thomas Edward Lawrence became involved in the 1916 Arab Revolt, fighting alongside guerilla forces, and made a legendary 300-mile journey through blistering heat. He wore Arab dress, and strongly identified with the people in his adopted lands. By 1918, he had a £20,000 price on his head. (Paperback)

A memorable selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #357th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending, get your copies of the books short-listed for this year’s Booker Prize, and get your seasonal gift-choosing done!

24 November 2023

“Fact is to me a hindrance to memory,” writes the narrator in this remarkable collage of passages evoking the ways in which past experiences have impressed themselves indelibly upon her. The sleepless nights of the title are not so much those of the narrator’s youth, though these are either well documented or implied and so the title is not not about them, but those of her present life, supposedly as “a broken old woman in a squalid nursing home”, waking in the night “to address myself to B. and D. and C.—those whom I dare not ring up until morning and yet must talk to through the night.” As if the narrator is a projection of the author herself, cast forward upon some distorting screen, the ten parts of the book make no distinction between verifiable biographical facts and the efflorescence of stories that arise in the author’s mind as supplementary to those facts, or in substitution for them. Elizabeth the narrator seems almost aware of the precarity of her role, and of her identity as distinct from but overlapping that of the author: “I will do this work of transformed and even distorted memory and lead this life, the one I am leading today.” Hardwick writes mind-woundingly beautiful sentences, many-commaed, building ecstatically, at once patient and careering, towards a point at which pain and beauty, memory and invention, self and other are indistinguishable. Spanning over fifty years, the book, the exquisite narrowness of focus of which is kept immediate by the exclusion of summary, frame or context, records the marks remaining upon the narrator of those persons, events or situations from her past that have not yet been replaced, or not yet been able to be replaced, by the ersatz experiences of stories about those persons, events and situations. “My father…is out, because I can see him only as a character in literature, already recorded.” Hardwick and her narrator are aware that one of the functions of stories is to replace and vitiate experience (“It may be yours, but the house, the furniture, strain toward the universal and it will soon read like a stage direction”), and she/she writes effectively in opposition to this function. Observation brings the narrator too close to what she observes, she becomes those things, is marked by them, passes these marks on to us in sentences full of surprising particularity, resisting the pull towards generalisation, the gravitational pull of cliches, the lazy engines of bad fiction. Many of Hardwick’s passages are unforgettable for an uncomfortable vividness of description—in other words, of awareness—accompanied by a slight consequent irritation, for how else can she—or we—react to such uninvited intensity of experience? Is she, by writing it, defending herself from, for example, her overwhelming awareness of the awful men who share her carriage in the Canadian train journey related in the first part, is she mercilessly inflicting this experience upon us, knowing it will mark us just as surely as if we had had the experience ourselves, or is there a way in which razor-sharp, well-wielded words enable both writer and reader to at once both recognise and somehow overcome the awfulness of others (Rachel Cusk here springs to mind in comparison)? In relating the lives of people encountered in the course of her life, the narrator often withdraws to a position of uncertain agency within the narration, an observatory distance, but surprises us by popping up from time to time when forgotten, sometimes as part of a we of uncertain composition, uncertain, that is, as to whether it includes a historic you that has been addressed by the whole composition without our realising, or whether the other part of we is a he or she, indicating, perhaps, that the narrator has been addressing us all along, after all. All this is secondary, however, to the sentences that enter us like needles: “The present summer now. One too many with the gulls, the cry of small boats on the strain, the soiled sea, the sick calm.”

It’s the time of the year when the New Zealand publishing industry reveals its best and biggest new titles, and many of these are stunning art books. Flora — Celebrating Our Botanical World is one of the gems. This looked stunning even when it was only a cover image and description when it was sold in a few months back, but it’s even better than expected. You can peep inside here. The title is slightly misleading as it made me think that this would only appeal to those who love botanical drawings and precise painterly renditions. In fact, the book draws from an array of disciplines across Te Papa’s collection, including the aforementioned, to textiles, jewellery, photography, furniture, and more. It has a good cross-section of historic and contemporary works, European-inspired as well as Pacifica focuses, and with 400 selections it’s a true treasure box. It’s lovely to look at, as well as being a source of excellent information and expert analysis. The essays are wide-ranging and contextually interesting. Flora is a fine example of cultural history as told through objects, and the texts add that layer that makes this publication a standout. Treat yourself or another art/flora lover.

A new book is a promise of good times ahead. Click through for your copies:

Our Strangers by Lydia Davis $45

Lydia Davis is a virtuoso at detecting the seemingly casual, inconsequential surprises of daily life and pinning them for inspection. In Our Strangers, conversations are overheard and misheard, a special delivery letter is mistaken for a rare white butterfly, toddlers learning to speak identify a ping-pong ball as an egg and mumbled remarks betray a marriage. In the glow of Davis's keen noticing, strangers can become like family and family like strangers. (Hardback)

”This is a writer as mighty as Kafka, as subtle as Flaubert and as epoch-making, in her own way, as Proust.” —Ali Smith

”Davis captures words as a hunter might and uses punctuation like a trap. Davis is a high priestess of the startling, telling detail, a most original and daring mind.” —Colm Toibin

A Shining by Jon Fosse (translated from Nynorsk by Damion Searles) $26

A man starts driving without knowing where he is going. He alternates between turning right and left, and finally he gets stuck at the end of a forest road. Soon it gets dark and starts to snow, but instead of going back to find help, he ventures, foolishly, into the dark forest. Inevitably, the man gets lost, and as he grows cold and tired, he encounters a glowing being amid the obscurity. (Paperback)

”A Shining can be read in many ways: as a realistic monologue; as a fable; as a Christian-inflected allegory; as a nightmare painstakingly recounted the next morning, the horror of the experience still pulsing under the words, though somewhat mitigated by the small daily miracle of daylight. I think the great splendour of Fosse’s fiction is that it so deeply rejects any singular interpretation; as one reads, the story does not sound a clear singular note, but rather becomes a chord with all the many possible interpretations ringing out at once. This refusal to succumb to the solitary, the stark, the simple, the binary – to insist that complicated things like death and God retain their immense mysteries and contradictions – seems, in this increasingly partisan world of ours, a quietly powerful moral stance.’” —Lauren Groff

”Fosse’s prose doesn’t speak so much as witnesses, unfolds, accumulates. It flows like consciousness itself. This is perhaps why A Shining feels so momentous, even at fewer than 50 pages. You never quite know where you’re going. But it doesn’t matter: you want to follow, to move in step with the rhythm of these words.” —Matthew Janney

Hangman by Maya Binyam $40

A man returns home to sub-Saharan Africa after twenty-six years living in exile in America. When he arrives, he finds that he doesn't recognise the country or anyone in it. Thankfully, someone at the airport knows him — a man who calls him brother. As they travel to this man's house, the purpose of his visit comes into focus: he is here to find his real brother, who is dying. In Hangman, Maya Binyam tells the story of this twisted odyssey, and of the phantoms and tricksters, aid workers and taxi drivers, the relatives, riddles and strangers that lead this man along a circuitous path towards the truth. Hangman is a strangely honest story of one man's stubborn search for refuge — in this world and the one that lies beyond it. (Hardback)

”Hangman beckons you into a zone that at first seems as clear, as blank, and as eerily sunny as the pane of a window. Then it traps you there, until you notice the blots, bubbles, and fissures in the glass — and then the frame itself, then the shatter. A clean, sharp, piercing — and deeply political — novel.” —Namwali Serpell

This Plague of Souls by Mike McCormack $40

The long-awaited next novel from the Goldsmiths Prize-winning author of Solar Bones. How do you rebuild the world? How do you put it back together? Nealon returns to his family home in Ireland for the first time in years, only to be greeted by a completely empty house. No heat or light, no furniture, no sign of his wife or child anywhere. It seems the world has forgotten that he even existed. The one exception is a persistent caller on the telephone, someone who seems to know everything about Nealon's life, his recent bother with the law and, more importantly, what has happened to his family. All Nealon needs to do is talk with him. But the more he talks the closer Nealon gets to the same trouble he was in years ago, tangled in the very crimes of which he claims to be innocent. Part roman noir, part metaphysical thriller, This Plague of Souls is a story for these fractured times, dealing with how we might mend the world and the story of a man who would let the world go to hell if he could keep his family together..(Hardback)

”This is the reason Mike McCormack is one of Ireland's best-loved novelists; he is the most modestly brilliant writer we have. His delicate abstractions are woven from the ordinary and domestic — both metaphysical and moving, McCormack's work asks the big questions about our small lives.” —Anne Enright

Forgotten Manuscript by Sergio Chejfec (translated from Spanish by Jeffrey Lawrence) $38

"Could anyone possibly believe that writing doesn't exist? It would be like denying the existence of rain." The perfect green notebook forms the basis for Sergio Chejfec's work, collecting writing, and allowing it to exist in a state of permanent possibility, or, as he says, "The written word is also capable of waiting for the next opportunity to appear and to continue to reveal itself by and for itself." This same notebook is also the jumping off point for this essay, which considers the dimensions of the act of writing (legibility, annotation, facsimile, inscription, typewriter versus word processor versus pen) as a way of thinking, as a record of relative degrees of permanence, and as a performance. From Kafka through Borges, Nabokov, Levrero, Walser, the implications of how we write take on meaning as well worth considering as what we write. This is a love letter to the act of writing as practice, bearing down on all the ways it happens (cleaning typewriter keys, the inevitable drying out of the bottle of wite-out, the difference between Word Perfect and Word) to open up all the ways in which "when we express our thought, it changes." (Paperback)

"It is hard to think of another contemporary writer who, marrying true intellect with simple description of a space, simultaneously covers so little and so much ground.” —Times Literary Supplement

Any Body: A comic compendium of important facts and feelings about our bodies by Katharina von der Gathen and Anke Kuhl $30

An honest, humorous and factual book for children and early teens who want to understand and feel at home with their own bodies. Sometimes we feel uncomfortable in our own skin, sometimes invincible. Katharina von der Gathen’s many years of experience working with children as a sex educator are the basis for this witty encyclopedia covering interesting facts about skin, hair and body functions alongside the questions that may affect us through puberty and beyond—gender identity, beauty, consent, self-confidence, how other people react and relate to us, and how they make us feel. With accessible and warm text, Any Body gently acknowledges common feelings of ambivalence about our bodies. Through showing body diversity and positivity, it encourages acceptance of self and others. The illustrations are relatably funny and include charts, cartoons and more—even a handy page of visual compliments. This compendium is an encouraging starting point for conversations with children navigating puberty and laying the foundations for body acceptance in a straightforward and highly entertaining way.

The Untamed Thread: Slow stitch to sooth the soul and ignite creativity by Fleur Woods $50

The Untamed Thread is the story of Fleur Woods’s journey from corporate world to creative life — woven with generous doses of the practical ways you can bring more creativity into your own life. Taking cues from the natural world we wander through Fleur’s contemporary fibre art practice to encourage and support you to find your own creative path. This inspiring creative guide invites you into Fleur’s art studio, near Upper Moutere. Her practice is as untamed as the New Zealand landscape that inspires her, free of rules, guided by intuition and joy in the process. Together we explore colour, texture, flora, textiles and stitch alongside the magic moments, happy accidents, perfect coincidences and ridiculous randomness of the creative process. Embracing the slow, contemplative nature of stitch we can reconnect our creative spirits to reimagine embroidery as a contemporary tool for mark making. This book wraps you in a warm blanket of nostalgia, grounds you in nature and inspires your senses to allow you to travel down your own creative path gathering all the precious little details meant for you along the way. (Flexibound)

Marigold and Rose: A fiction by Louise Glück $44

The twins, Marigold and Rose, in their first year, begin to piece together the world as they move between Mother’s stories of ‘Long, long ago’ and Father’s ‘Once upon a time’. Impressions, repeated, begin to make sense. The rituals of bathing and burping are experienced differently by each. The story is about beginnings, each of which is an ending of what has come before. There is comedy in the progression, the stages of recognition, and in the ironic anachronisms which keep the babies alert, surprised, prescient and resigned. Charming, resonant, written with Gluck’s characteristic poise and curiosity, Marigold and Rose unfolds as a new kind of creation myth. "Marigold was absorbed in her book; she had gotten as far as the V." So begins Marigold and Rose, Louise Gluck's astonishing chronicle of the first year in the life of twin girls. Imagine a fairy tale that is also a multigenerational saga; a piece for two hands that is also a symphony; a poem that is also, in the spirit of Kafka's ‘The Metamorphosis’, an incandescent act of autobiography.

To the Ice by Thomas Tidholm and Anna-Clara Tidholm $28

Ida, Max and Jack go to the creek one winter’s day. They play on an ice floe then find themselves floating away—all the way to the polar ice, with just a box, a branch and some sandwiches. “You probably don’t think it’s true, and we didn’t either, not even while it was happening.” They find an old hut, meet penguins, see extraordinary things and, after testing their resources in this dramatic land of ice and snow, come home safe at the end of the day. “What shall we say about where we’ve been?” asked Max. “Tell the truth,” I said. “We don’t know.” (Hardback)

Dialogue with a Somnambulist: Stories, essays, and a portrait gallery by Chloe Ardjis $36

Renowned internationally for her lyrically unsettling novels Book of Clouds, Asunder and Sea Monsters, the Mexican writer Chloe Aridjis crosses borders in her writing as much as in life. Now, collected here for the first time, her stories, essays and pen portraits reveal an author as imaginatively at home in the short form as in her longer fiction. Conversations with the presences who dwell on the threshold of waking and reverie, these pieces will stay with you long after the lamps have flickered out. At once fabular and formally innovative, acquainted with reverie and rigorous report, sensitive to the needs of a wider ecology yet familiar with the landscapes of the unconscious, her texts are both dream dispatches and wayward word plays infused with the pleasure and possibilities of language. In this collection of works, we meet a woman guided only by a plastic bag drifting through the streets of Berlin who discovers a nonsense-named bar that is home to papier-mâché monsters and one glass-encased somnambulist. Floating through space, cosmonauts are confronted not only with wonder and astonishment, but tedium and solitude. And in Mexico City, stray dogs animate public spaces, “infusing them with a noble life force.” In her pen portraits, Aridjis turns her eye to expats and outsiders, including artists and writers such as Leonora Carrington, Mavis Gallant, and Beatrice Hastings. (Paperback)

The Sewing Girl’s Tale: A story of crime and consequences in Revolutionary America by John Wood Sweet $40

An account of the first published rape trial in American history and its long, shattering aftermath, revealing how much has changed over two centuries — and how much has not. On a moonless night in the summer of 1793 a crime was committed in the back room of a New York brothel — the kind of crime that even victims usually kept secret. Instead, seventeen-year-old seamstress Lanah Sawyer did what virtually no one in US history had done before: she charged a gentleman with rape. Her accusation sparked a raw courtroom drama and a relentless struggle for vindication that threatened both Lanah's and her assailant's lives. The trial exposed a predatory sexual underworld, sparked riots in the streets, and ignited a vigorous debate about class privilege and sexual double standards. The ongoing conflict attracted the nation's top lawyers, including Alexander Hamilton, and shaped the development of American law. Eventually, Lanah Sawyer did succeed in holding her assailant accountable — but at a terrible cost to herself. (Paperback)

Artichoke to Zucchini: An alphabet of delicious things from around the world by Alice Oehr $30

A is for artichokes and long spears of asparagus. It's for bright, creamy avocados and salty little anchovies… From apple pie to zeppole, and everything in between, Artichoke to Zucchini introduces young readers to fruit, vegetables, and dishes from around the globe. Full of tasty favourites and delicious new discoveries, it's sure to lead to inspiration in the kitchen!

Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting is a favourite with many bookies to win this year’s Booker Prize. (which will be announced in just a few days!). From the author of the excellent Skippy Dies comes a dazzlingly intricate and poignant tragicomedy about family, fortune, and the struggle to be a good man at the end of the world. Exceptionally well-reviewed since its publication, the story is told by the four distinct voices of the Barnes family. Meet Dickie whose car business is going under, but he's out in the woods preparing for the actual end of the world. Meanwhile, his wife Imelda is selling off her jewellery on eBay, their teenage daughter, Cass, is determined to drink her way through the whole thing, and PJ, aged 12, is disappearing into the video game portal and hatching a plan. There’s trouble ahead. Move over Skippy, The Bee is here. This should be on your reading pile this summer.

“Paul Murray’s saga, The Bee Sting, set in the Irish Midlands, brilliantly explores how our secrets and self-deceptions ultimately catch up with us. This family drama, told from multiple perspectives, is at once hilarious and heartbreaking, personal and epic. It’s an addictive read.” —The Booker Judges

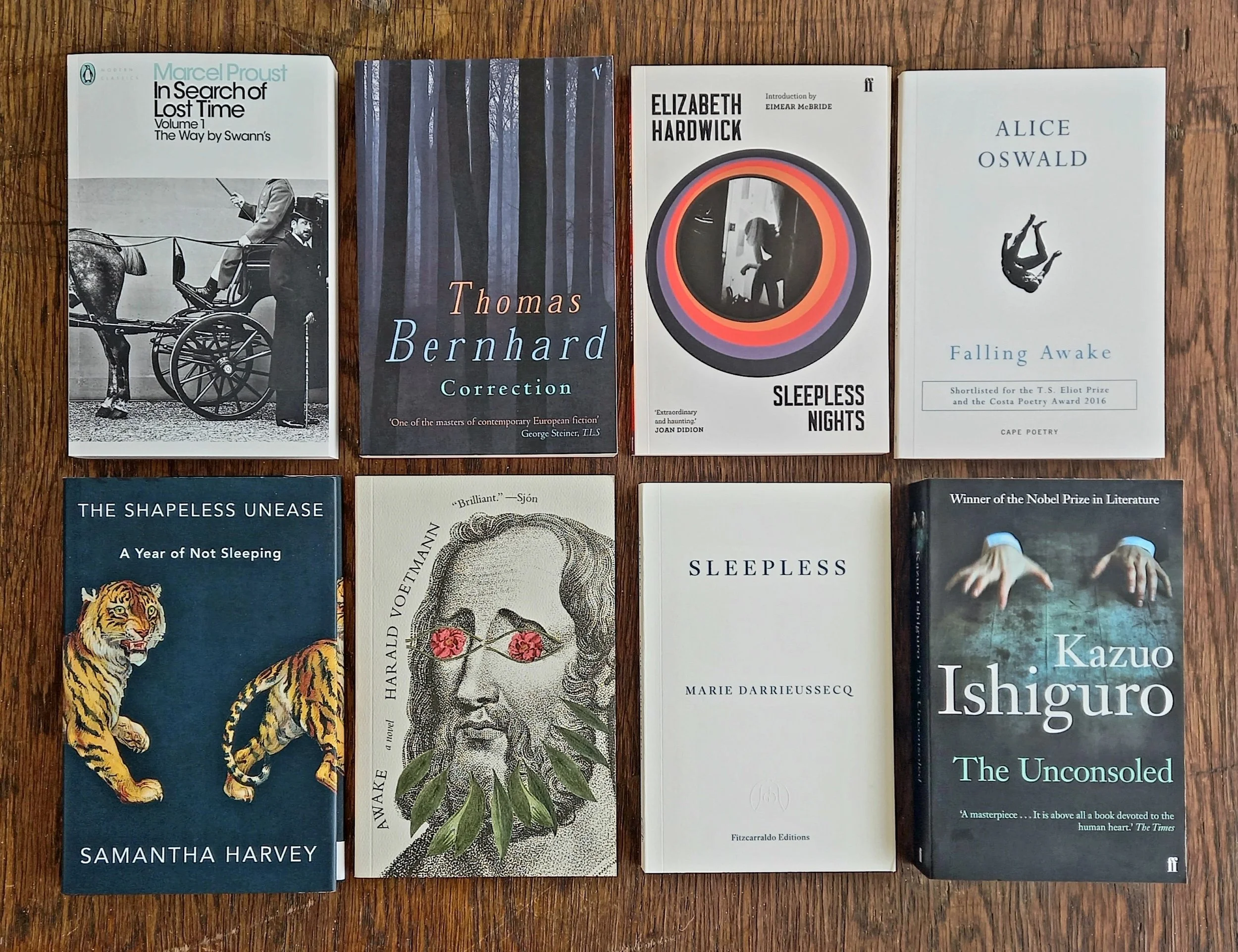

A selection of insomniac books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

GARGOYLES by Thomas Bernhard (translated from German by Richard and Clara Winston)

“The catastrophe begins with getting out of bed.” Gargoyles (first published in 1967 as Verstörung (“Disturbance”)) is the book in which Bernhard laid claim both thematically and stylistically to the particular literary territory developed in all his subsequent novels. In the first part of the book, set entirely within one day, the narrator, a somewhat vapid student accompanying his father, a country doctor, on his rounds, tells us of the sufferings of various patients due to their mental and physical isolation: the wealthy industrialist withdrawn to his dungeon-like hunting lodge to write a book he will never achieve (“’Even though I have destroyed everything I have written up to now,’ he said, ‘I have still made enormous progress.’”), and his sister-companion, the passive victim of his obsessions whom he is obviously and obliviously destroying; the workers systematically strangling the birds in an aviary following the death of their owner; the musical prodigy suffering from a degenerative condition and kept in a cage, tended by his long-suffering sister. The oppressive landscape mirrors the isolation and despair of its inhabitants: we feel isolated, we reach out, we fail to reach others in a meaningful way, our isolation is made more acute. “No human being could continue to exist in such total isolation without doing severe damage to his intellect and psyche.” Bernhard’s nihilistic survey of the inescapable harm suffered and inflicted by continuing to exist is, however, threaded onto the doctor’s round: although the doctor is incapable of ‘saving’ his patients, his compassion as a witness to their anguish mirrors that of the author (whose role is similar). In the second half of the novel, the doctor’s son narrates their arrival at Hochgobernitz, the castle of Prince Saurau, whose breathlessly neurotic rant blots out everything else, delays the doctor’s return home and fills the rest of the book. This desperate monologue is Bernhard suddenly discovering (and swept off his feet by) his full capacities: an obsessively looping railing against existence and all its particulars. At one stage, when the son reports the prince reporting his dream of discovering a manuscript in which his son expresses his intention to destroy the vast Hochgobernitz estate by neglect after his father’s death, the ventriloquism is many layers deep, paranoid and claustrophobic to the point of panic. The prince’s monologue, like so much of Bernhard’s best writing, is riven by ambivalence, undermined (or underscored) by projection and transference, and structured by crazed but irrefutable logic: “‘Among the special abilities I was early able to observe in myself,’ he said, ‘is the ruthlessness to lead anyone through his own brain until he is nauseated by this cerebral mechanism.’” Although the prince’s monologue is stated to be (and clearly is) the position of someone insane, this does not exactly invalidate it: “Inside every human head is the human catastrophe corresponding to this particular head, the prince said. It is not necessary to open up men’s heads in order to know that there is nothing inside them but a human catastrophe. ‘Without this human catastrophe, man does not exist at all.'”

A new book is a promise of good times ahead.

Read our #356th NEWSLETTER and find out what we’ve been reading and recommending, get your copies of the books short-listed for this year’s Booker Prize, and choose some other books as well!

17 November 2023

Thread Ripper by Amalie Smith (translated from Danish by Jennifer Russell)

Perhaps, he thought in a rare moment of self-reflection, or in a moment of rare self-reflection, he wasn’t sure which, I have become so accustomed to writing my so-called fictional reviews, to writing my so-called reviews in a fictional manner or even, more confusingly, in an autofictional manner so that they are not immediately recognised as the fictions they are, that I have proverbialised myself into a corner and am incapable of writing a straight review, if there is even such a thing, or a review just written as a review, there might be such a thing as that, he thought, without the novelistic trappings of my approach, my distancing and deflection tricks, my wriggling away from the task at hand and from the possibility that I am not up to the task at hand, he thought, perhaps all my trickeration, so to call it, is just a way of concealing my incapability, from myself at least for surely no-one else is fooled, he thought. None of this helped, he thought, this self-reflection, so to call it, makes me more incapable rather than less, makes anything that might pass for a review, or even for a meta-review, less possible, I have thought myself to a standstill, he thought, unless of course I create a fictional reviewer to write the reviews for me, a fictional reviewer who could write a straight review, a review written as a review, that elusive goal that for me is now unreachable, at least without some trickeration, I have got to the point at which only a fake reviewer can write a real review. Anyway, anyone but me. I wonder how my fictional reviewer will approach this book, Thread Ripper, he thought. Thread Ripper is written in two parallel sequences or threads on the facing pages of each opening, and each of those threads has its own approach to the matters that inform them both. My reviewer would probably find themselves obliged to begin or find it convenient to begin with a description of how the verso pages carry an account, if that is the right word, of the author’s researches and considerations of the history of weaving and computer programming, which turn out to be the same thing, at least in the author’s concurrent artistic practice, so to call it, here also described, and which turn out to be the same thing also as neurology and linguistics, or at least to have typological parallels to neurology and linguistics, if these even warrant separate terms, which the fictional reviewer may speculate on at some length, or not, these recto pages deal with matters outside the author’s head, matters of what could be termed fact, even though the term fact could be applied in this instance to some quite interesting philosophical speculations, speculations about things that may actually be the case, which, for the fictional reviewer, is as good a definition of the term as any. The recto pages are concerned with problems of knowing, the fictional reviewer may begin, or may conclude, whereas the verso pages are concerned with problems of feeling, so to call it, not that in either case should we assume the so-called problems to be necessarily problematic, although in many cases in both strands they are, the recto pages are concerned with what is going on inside the author’s head, with matters subject to temporal mutabilities, temporal mutabilities being an example, or being examples, of the sort of words a fictional reviewer might use when writing a review as a review but not making a very good job of it, though it is unclear whose fault that might be, does he have a responsibility for the performance of this fictional reviewer he has devised to do his job, he supposed he did have some such responsibility but he couldn’t help starting to wonder if successfully creating a character who fails to write well might be more of a success than a failure, though it would be, he supposed, a failure at his stated aim of achieving by the employment of a fictional reviewer the sort of straight review that he found himself these days incapable of writing, he wanted the fictional reviewer to write a real review, after all, a fictional review, which would not need to be actually written and which in this instance he could easily refer to as being wholly positive about this interesting book Thread Ripper, which he has read and enjoyed and which started in his mind, if it warrants to be so called, some quite interesting speculations and chains of thought of his own, and which he could suppose, to make his task easier, his fictional reviewer has also read and enjoyed, they are not so different after all, he thought, such a fictional review would not realise his intention or fulfil the purpose of the reviewer, he had intended the fictional reviewer to review the book in a straightforward way, even though he, even if this intention was by some chance realised, looked as if he would in any case treat the whole exercise, to his shame, as so often, as something of a sentence gymnasium. He would like to write in a straightforward way, he thought, to say, in this instance, I like this book and what is more I think you should buy it because I think you would like it too, but he could not help making the whole exercise into a sentence gymnasium, I never can resist a sentence gymnasium, he thought, these days less than ever, show me a sentence gymnasium or some relatively straightforward task that I could treat as a sentence gymnasium, pretty much anything can be so treated, he realised, and I am lost, he thought, whatever I attempt I fail, I am lost in the fractals of my sentence gymnasiums, or sentence gymnasia, rather, he corrected himself, my plight is worse than I thought, he thought. In Thread Ripper the author on the verso dreams, the fictional reviewer might point out, he thought, or he hoped the fictional reviewer would point out or remember to point out even if they didn’t get so far as to actually point out, according to the verso pages the author dreams and longs, and the author on the recto pages, if we are not at fault for calling either personage the author, programmes her computer with an algorithm to weave tapestries but also with an algorithm to write poetry, the results of which are included on these recto pages, if the author of those pages is to be believed, he didn’t see why not and he thought it unlikely that his fictional reviewer would have any reservations in regard to the authenticity of these poems, so to call them, or rather to the artificial authorship of the poems and of the so-called ‘artificial’ intelligence behind them, any productive system, any arrangement of parts that can produce something beyond those parts, is a sort of intelligence, he thought, though he evidently hadn’t thought this very hard. All thought is done by something very like a machine, even if this is not very like what we commonly term machines, he reasoned, reducing the meaning of his statement almost to nothing while doing so, it is a good thing I am not writing this review myself, it is a good thing I have a fictional reviewer to write the review, a fictional reviewer whom I can make ridiculous without making myself ridiculous, he thought, unconvincingly he had to admit though he didn’t admit this of course to anyone but himself, the universe is full of mess, a mess we are in a constant struggle to reduce. “The digital has become a source not of order, as we had hoped, but of mess, an accumulation of images and signs that just keeps on growing,” writes the author of Thread Ripper. “For humans it’s a mess; a machine can see right through.” Perhaps there is a difference between machine intelligence, which compounds, and human intelligence, which reduces, he thought briefly and then abandoned this thought, perhaps my fictional reviewer will have this thought and perhaps my fictional reviewer will be able to think it through and make something of it, fictional characters often think better than the authors who invent them, fictional characters are themselves a kind of machine for thinking with, artificial characters with artificial thoughts, if there can be such things, perhaps intelligence is the only thing that can never be artificial, he thought, though we might have to change the meanings of several words to make this statement make sense. “I hear on the radio that the human brain at birth is a soup of connections, that language helps us reduce them,” writes the author in Thread Ripper. “The more we learn, the fewer the connections.” Does grammar, then, work as a kind of algorithm, he wondered, or he wondered if his fictional reviewer might be induced to wonder, is it grammar that forms our thoughts by reducing them to the extent that we may affect on occasion to make some sense, whether of not we are right, which is, really, unimportant, the grammar is what matters not the content, is this what Ada Lovelace, who died before she could describe it, referred to as the calculus of the nervous system, could he actually end his sentence with a question mark, he wondered, the question mark that belonged to this Ada Lovelace question, or was he too tangled in his sentence to find its end?

Some books are a pleasure to look at, to handle, and to have close at hand for inspiration. The way a book is designed can alter your interaction with it. The choice of font, layout, paper stock, binding, and the content/space (the white of the page) ratio all affect your reading experience. Whether this is a novel or an art book, the design of a book should be pleasing, and yet unnoticeable. It should feel right. If you are interested in design, like Japanese aesthetics, and like a set, then these two books are awaiting your pleasure. I’ve owned a copy of Wa: The Essence of Japanese Design for a few years and I never tire of it. Wa is not only filled with gorgeous examples of wood, metal, and textile objects, it's a design object in itself. Beautifully bound with striking stitching, the pages are made from folded fine paper so from the moment you pick it up it feels special. Within the covers of the book, the pages carry the essence of Japanese aesthetic with typographic design and placement of images on the page which are pleasing and thoughtfully arranged. Split into different media (textile, wood, metal, etc), each chapter has an essay discussing the area and the contemporary approach to each. It’s altogether a stunning book. And its partner, Iro: the Essence of Colour in Japanese Design, is just as compelling.

A new book is a promise of good times ahead. Click through for your copies:

Cuddy by Benjamin Myers $37

“Part poetry, part electricity, this story carries relics between the ephemeral and the eternal with all the disarming vitality of a truly illuminated text.” —Goldsmiths Prize judges' citation

Cuddy is a bold and experimental retelling of the story of the hermit St. Cuthbert, unofficial patron saint of the North of England. Incorporating poetry, prose, play, diary and real historical accounts to create a novel like no other, Cuddy straddles historical eras — from the first Christian-slaying Viking invaders of the holy island of Lindisfarne in the 8th century to a contemporary England defined by class and austerity. Along the way we meet brewers and masons, archers and academics, monks and labourers, their visionary voices and stories echoing through their ancestors and down the ages. And all the while at the centre sits Durham Cathedral and the lives of those who live and work around this place of pilgrimage their dreams, desires, connections and communities. Winner of the 2023 Goldsmiths Prize.

”A sensational piece of storytelling. The symbiosis of poetry and story, of knowledge and deep love, marks out Cuddy as a singular and significant achievement.” —Guardian

”A polyphonic hymn to a very specific landscape and its people. At the same time, it deepens his standing as an arresting chronicler of a broader, more mysterious seam of ancient folklore that unites the history of the British Isles as it's rarely taught.” —Observer

Flora: Celebrating our botanical world edited by Carlos Lehnebach, Claire Regnault, Rebecca Rice, Isaac Te Awa, and Rachel Yates $80

This splendid large-format book mines Te Papa's collections to explore and expand upon the way we think about our botanical world and its cultural imprint. It features over 400 selections by a cross-disciplinary curatorial team that range from botanical specimens and art to photography, furniture, jewellery, tivaevae, applied art, textiles, stamps and more. Flora's twelve essays provide a deeper contextual understanding of different topics, including the unique characteristics of New Zealand flora as well as how artists and cultures have used flora as a motif and a subject over time. Very desirable, very browsable, very givable.

I Have the Right: An affirmation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child illustrated by Reza Dalvand $30

Beautifully illustrated and unfortunately urgently relevant at the moment, this book introduces children and reminds adults of the basic rights of children that no adult or government should violate for any reason. I have the right to have a name and a nationality. I have the right to the best healthcare. I have the right to an education. I have the right to a home where I can thrive. Adopted in 1989 and ratified by these 190 countries, the UNCRoC promises to defend the rights of children and to keep them safe, respected, and valued. Dalvand's stunning illustrations speak to children all around the world, some of whose rights are often challenged and must be protected every day. Among its other articles guaranteeing children’s access to food, water, safety and wellbeing, the UNCRoC specifically “condemns the targeting of children in situations of armed conflict and direct attacks on objects protected under international law, including places that generally have a significant presence of children, such as schools and hospitals.”

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo $35

Short-listed for this year’s Booker Prize, Western Lane is a beautiful and moving debut novel about grief, sisterhood, and a teenage girl’s struggle to transcend herself. Gopi has been playing squash since she was old enough to hold a racket. When her mother dies, her father enlists her in an intense training regime, and the game becomes her world. Her life is reduced to the sport’s rhythms: the serve, the volley, the drive, the shot, and its echo.

What the Booker judges say: "Skilfully deploying the sport of squash as both context and metaphor, Western Lane is a deeply evocative debut about a family grappling with grief, conveyed through crystalline language which reverberates like the sound ‘of a ball hit clean and hard…with a close echo’.” Now available in paperback.

Corey Fah Does Social Mobility by Isabel Waidner $37

This is the story of Corey Fah, a writer on the cusp of a windfall, courtesy of the Social Evils prize committee, for whom the actual gong — and with it the prize money - remains tantalizingly out of reach. Neon beige, with UFO-like qualities, the elusive trophy leads Corey, with partner Drew and surprise eight-legged companion Bambi Pavok, on a spectacular detour through their childhood in the Forest 3 via an unlikely stint on reality TV. Navigating those twin horrors, through wormholes and time loops, Corey learns — the hard way — the difference between a prize and a gift. Both radiant and revolutionary, Isabel Waidner's fiction gleefully takes a hammer to false binaries, boundaries and borders, turning walls into bridges and words into wings. Fierce, fluid and funny, they free us to imagine another way of being. This is a novel about coming into one's own, the labour of love, the tendency of history to repeat itself and the pitfalls of social mobility. It's about watching TV with your lover. Waidner, whose Sterling Karat Gold was awarded he 2022 Goldsmiths Prize, has a unique, disorienting, and very enjoyable voice.

”A piece of winged originality.” —Ali Smith

”A provocative act of resistance to our morally slippery times. Reading Waidner is like plugging into an electric socket of language and ideas.” —Guardian

”The writer everyone is talking about — and deservedly so. Their explosive sensibility and style are as far removed from mediocre prose and middle-class manners as you can imagine.” —Bernardine Evaristo

”Buckle up! Corey Fah Does Social Mobility is a head-spinning, mind-bending roller coaster of fun, horror, and subversion. I love it.” —Kamila Shamsie

At the Bach by Joy Cowley, illustrated by Hilary Jean Tapper $30

Cowley’s simple rhythmic text is perfectly matched with Tapper’s warm and gentle illustrations to capture the common childhood experience of staying in a bach by the sea in summer. An instant favourite.

The Future Future by Adam Thirlwell $37

It's the eighteenth century, and Celine is in trouble. Her husband is mostly absent. Her parents are elsewhere. And meanwhile men are inventing stories about her — about her affairs, her sexuality, her orgies and addictions. All these stories are lies, but the public loves them — spreading them like a virus. Celine can only watch as her name becomes a symbol for everything rotten in society. This is a world of decadence and saturation, of lavish parties and private salons, of tulle and satin and sex and violence. It's also one ruled by men — high on colonial genocide, natural destruction, crimes against women and, above all, language. To survive, Celine and her friends must band together in search of justice, truth and beauty. A wild story of female friendship, language and power, from France to colonial America to the moon, from 1775 to this very moment — a historical novel like no other.

”Adam Thirlwell considers the celestial and the political on the same plane, creating wondrous new ways of seeing history, nature, friendship and time. He weaves together so many wisps of reality, and the result is a radically beautiful new novel that is funny, touching, memorable and bright.” —Sheila Heti

”Thirlwell's prose is hypnotic and coolly beautiful. The writing is full of dreamlike leaps, not just at the level of plot, but in its sentences, too. The Future Future has a beauty and a mysterious power that reflect its enigmatic protagonist.” —Guardian

”A book filled with imaginative leaps, brave decisions and tiny details that give delight.” —Colm Toibin

Take What You Need by Idra Novey $25

Take What You Need traces the parallel lives of Jean and her beloved but estranged stepdaughter, Leah, who's sought a clean break from her rural childhood. In Leah's urban life with her young family, she's revealed little about Jean, how much she misses her stepmother's hard-won insights and joyful lack of inhibition. But with Jean's death, Leah must return to sort through what's been left be-hind. What Leah discovers is staggering: Jean has filled her ramshackle house with giant sculptures she's welded from scraps of the area's industrial history. Set in the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia, Take What You Need explores the continuing mystery of the people we love most, zeroing in on the joys and difficulties of family with great verve and humour.

”Novey fully renders the inarticulable parts of artmaking - the antagonism of an artist's material, the pleasure in that difficulty, the way it troubles tidy ideasof legacy.” —Raven Leilani

Determined: Life without free will by Robert Sapolsky $40

Robert Sapolsky's Behave, his now classic account of why humans do good and why they do bad, pointed toward an unsettling conclusion: We may not grasp the precise marriage of nature and nurture that creates the physics and chemistry at the base of human behavior, but that doesn't mean it doesn't exist. Now, in Determined, Sapolsky takes his argument all the way, mounting a full-frontal assault on the pleasant fantasy that there is some separate self telling our biology what to do. Determined offers a synthesis of what we know about how consciousness works — the tight weave between reason and emotion and between stimulus and response in the moment and over a life. One by one, Sapolsky tackles all the major arguments for free will and takes them out, cutting a path through the thickets of chaos and complexity science and quantum physics, as well as touching ground on some of the wilder shores of philosophy. He shows us that the history of medicine is in no small part the history of learning that fewer and fewer things are somebody's "fault". Yet, as he acknowledges, it's very hard, and at times impossible, to uncouple from our zeal to judge others and to judge ourselves. Sapolsky applies the new understanding of life beyond free will to some of our most essential questions around punishment, morality, and living well together. Sapolsky argues that while living our daily lives recognising that we have no free will is going to be monumentally difficult, doing so is not going to result in anarchy, pointlessness, and existential malaise. Instead, it will make for a much more humane world.

Eve: How the female body drove 200 million years of human evolution by Cat Bohannon $42

Eve is not only a sweeping revision of human history, it's an urgent and necessary corrective for a world that has focused primarily on the male body for far too long. Bohannon's findings, including everything from the way C-sections in the industrialized world are rearranging women's pelvic shape to the surprising similarities between pus and breast milk, will completely change what you think you know about evolution and why Homo sapiens have become such a successful and dominant species, from tool use to city building to the development of language.

”Utterly fascinating. This book should revolutionise our understanding of human life. It is set to become a classic.” —George Monbiot

”Eve was immeasurably useful to me in my life-long quest to understand my own body. I highly recommend it to anyone who is on the same journey.” —Hope Jahren

Artists in Antarctica edited by Patrick Shepherd $80

What transformation happens when writers, musicians and artists stand in the vast, cold spaces of Antarctica? This book brings together paintings, photographs, texts and musical scores by Aotearoa New Zealand artists who have been to the ice. It explores the impact of this experience on their art and art process, as well as the physical challenges of working in a harsh and unfamiliar environment. Antarctic science, nature and human history are explored through the creative lens of some of New Zealand's most acclaimed artists, composers and writers, including Lloyd Jones, Laurence Aberhart, Nigel Brown, Gareth Farr, Dick Frizzell, Anne Noble, Virginia King, Owen Marshall, Grahame Sydney, Ronnie van Hout, Phil Dadson, and Sean Garwood.

A Passion for Whisky: How the tiny island of Islay creates malts that captivate the world by Ian Wisniewski $60

”Ian Wisniewski is one of our foremost drinks writers. At once affectionate, knowledgeable and entertaining, this engaging book is essential reading for any fans of Islay whisky.” —Charles MacLean

Individual profiles of Islay's 13 distilleries include tasting notes for selected malts that illustrate the incredible range of peated styles produced, together with a section on tasting techniques, making this an indispensable guide for Scotch whisky lovers.

Short-listed for this year’s Booker Prize, Western Lane is a beautiful and moving debut novel about grief, sisterhood, and a teenage girl’s struggle to transcend herself. Gopi has been playing squash since she was old enough to hold a racket. When her mother dies, her father enlists her in an intense training regime, and the game becomes her world. Her life is reduced to the sport’s rhythms: the serve, the volley, the drive, the shot, and its echo.

What the Booker judges say: "Skilfully deploying the sport of squash as both context and metaphor, Western Lane is a deeply evocative debut about a family grappling with grief, conveyed through crystalline language which reverberates like the sound ‘of a ball hit clean and hard…with a close echo’.”

The Booker Prize shortlist for 2023.

Click through to find out more:

Western Lane (PB) or (HB)

Study for Obedience (HB) or (PB)

If I Survive You (PB) or (HB)