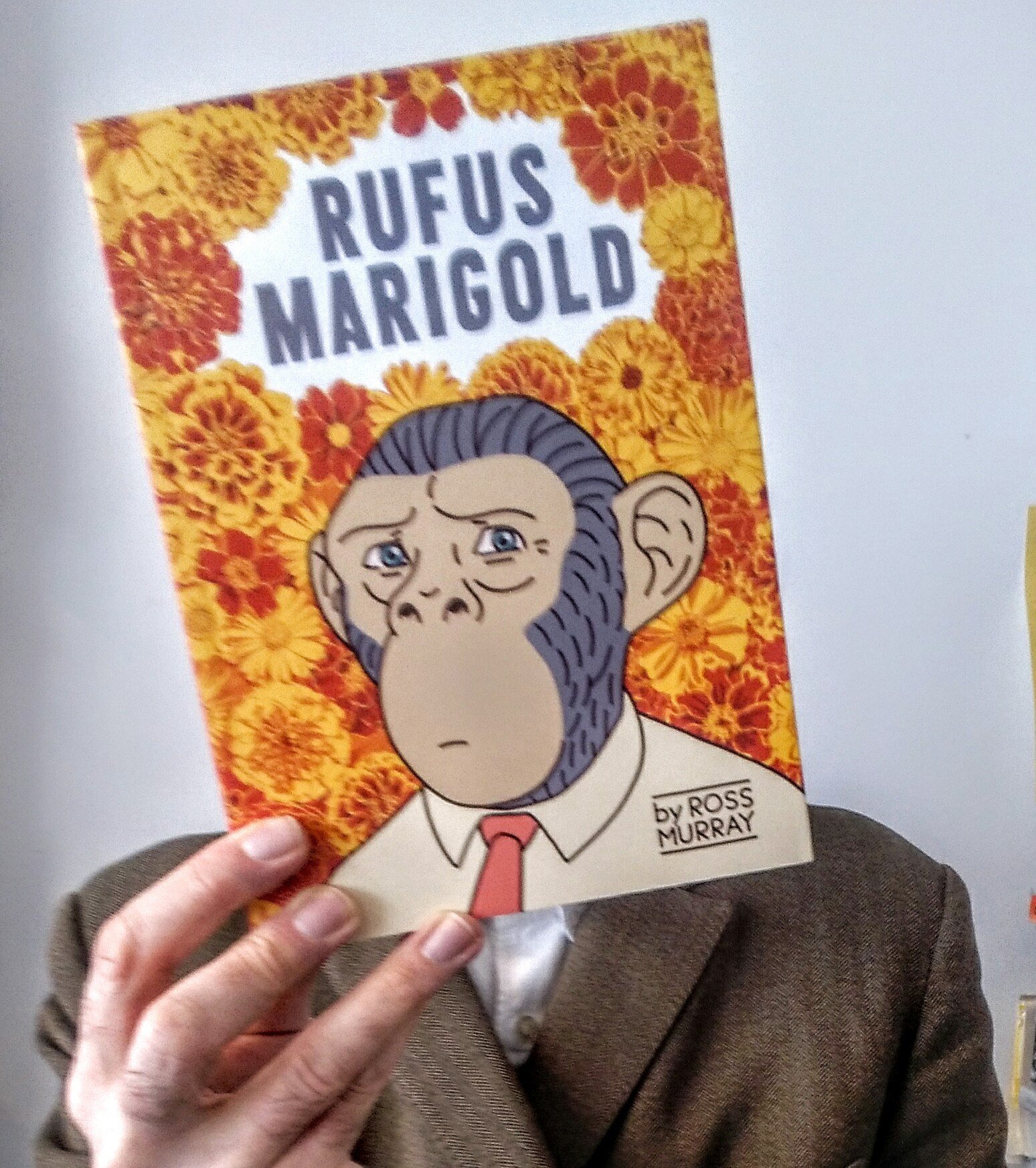

He had read the book so there was no reason why he should not by now have also written the review. He had, however, not written the review and he was, for some reason, feeling disinclined to start writing the review, even though the review had to be finished soon, in fact the sooner the better, to go out in the newsletter, preferably before dinner, and he could feel this urgency sitting like a physical pressure, even though he could not quite locate where upon his body this seemingly physical pressure was applied, or was applying itself. Presumably if he was affected by a seemingly physical pressure it would be experienced physically, or seem to be, which is the same thing, his body was all he had, so maybe this physical pressure was applying itself, or being applied to, his head, or his back, or his stomach, he could certainly feel what could be the cumulative effects of such pressure in each of those locations, or in all of those locations, he could not decide which, though he also could not decide whether what he felt in those physical locations was the effect of the seemingly physical pressure to write the review of Rufus Marigold, a pressure that was not actually physical but only seemingly physical in that it was experienced physically and his body was all he had, or of some other seemingly physical but not actually physical pressure, and here he had to stop himself from considering the various candidates for causing this seemingly physical but not actually physical pressure, and he thought there might be quite a few, better not to go there, or, indeed, of some actually physical pressure applying itself or being applied to those locations in his body, and here again there were various candidates for the cause of this, gravity not least among them. This always happened to him. Some minor detail or aspect of the so-called exterior world, or some comment or nuance by someone in the so-called exterior world, or some observation made by him, usually involuntarily, of the so-called exterior world, or of a person therein, would trigger a plausibly endless chain of monologue, either endlessly discursive or endlessly reiterative, in the so-called interior world, achieving nothing but underlining the apparent separation, or separateness, if there is a distinction to be made, of the so-called exterior world and the so-called interior world, causing the two to, if he could indulge the metaphor, rotate in opposite directions and lose touch. Once a thought has been thought it cannot be unthought, but does it need to be rethought and rethought? Rufus Marigold, the eponymous protagonist, if protagonist is not too generous a word, of the graphic novel Rufus Marigold, has a somewhat similar problem, he thought. Anything that Rufus Marigold cares about immediately triggers (can a trigger be anything other than immediate? he wondered. Can there be such a thing as a slow trigger? A delayed trigger?) in him a monologue to the effect that he is repellent, useless and a failure, or perhaps, sometimes, not so much that he is repellent, useless and a failure as that others will inevitably regard him as repellent, useless and a failure whether he is repellent, useless and a failure or not. Once this thought has been thought it cannot be unthought and Rufus will make the worst of any available situation that could make him seem, at least to himself and, if possible, to others, repellent, useless and a failure. Rufus sees himself as a chimpanzee, but nobody around him seems to see him as a chimpanzee. The separation of Rufus’s internal and external worlds, so to call them, is unbridgeable in either direction. Anxiety casts forward and overwrites desires with fears, but anxiety at least indicates the presence of desires, and therefore of hopes. Desires cannot be disappointed nor hopes dashed if desires and hopes do not exist, after all, and anxiety is, for all else that it is that we would rather it was not, an indication of something that its sufferer values. Anxiety identifies what is valuable and attempts to sully it or to put it beyond the sufferer’s grasp, but anxiety at least finds value. Anxiety is a capable ailment, though it feels incapable; it is active, though it seems to devastate action. He was a little nostalgic for anxiety, he thought, for its alternative is despair. Nothing written confidently was ever worth reading, he conjectured, not that there was any danger of that in his case, so, if only he could make himself anxious, he thought, he could at least write the review of Rufus Marigold that he needed to write, even though anyone who read it would immediately either recognise it to be vapid and ill-written or, failing that, fail to perceive anything in it that was not vapid and ill-written, or at least not entirely so, or, at best, he would continue to believe that anyone who read it had immediately recognised it as vapid and ill-written whether they had in fact found it vapid and ill-written or not. Same difference. At least the job would be done. At least Rufus Marigold had had the intensely funny and tragic graphic novel he had drawn about his anxiety published, by New Zealand’s Earth’s End Publishing, no less, even if he had agreed to someone called Ross Murray having his name put on it. Or perhaps, he thought, this ‘Ross Murray’ is just a persona invented by Rufus Marigold to deflect attention away from the nubs of his anxiety, to represent him in the so-called exterior world, to help him, at a safe remove, to function. That could be a useful tool, he thought, staring at the blank screen where his review of the book would have appeared if it had been going to appear. If I could access my anxiety I would use that.

Grace keeps centred with martial arts. Jeet Kune Do is her lifesaver, but will it be enough to get her through the summer? Can the words of Bruce Lee hold the world steady when everything is about to change? Grace is eighteen, working cleaning motel rooms, hoping she can save enough to go to uni, worried about her Mum, and watching out for her Gran. She’s a teen with more responsibility than most, and when her childhood friend, Charlie, jumps out of a suitcase (literally!) unexpectedly in front of her, life’s going to get a little more chaotic. Fall back a few years. Charlie and Grace met when they were five and were inseparable. Grace, a small Asian overprotected child, and Charlie, with his achondroplasia, are drawn to each other instantly and share a curiosity for the world and a fierce loyalty to each other. When Charlie’s academic mother gets a posting overseas, Grace feels abandoned, and has never forgiven Charlie for not keeping in touch. Now he’s back, their friendship is rekindled and it’s not what either of them expected. If this was the most complex issue in Grace’s life, no problem. But there are greater mysteries. Frustrated by her mother’s refusal to tell her anything substantial about her birth in Taiwan or her father who died, Grace is determined to find out more. A DNA test comes back with a surprising result, but her Mum’s in a precarious state, especially after Gran dies. Grace wants to confront her, but doesn’t want to tip her over the edge. Mandy Hager’s Gracehopper is brilliant; she writes about PTSD, bullying, relationships, drugs, trauma, and difference with sensitivity and honesty. Grace and Charlie are complex and compelling characters, who you can’t help but like. This is a novel for older teens about love, acceptance and forgiveness. Highly recommended.

Click through to our website for your copies of these new books!

The Vast Extent: On seeing and not seeing further by Lavinia Greenlaw $50

An ingenious constellation of ‘exploded essays’ about light and image, seeing and the unseen. Each is a record of how thought builds and ideas emerge, aligning art, myth, strange voyages, scientific scrutiny and a poet's response so that they cast light upon each other. Ranging across caves, seasickness, early photography, boredom, wonder, mountains, mice, the body and its shadow, from the Arctic at midwinter to a shingle spit in Norfolk at midsummer, Lavinia Greenlaw invites us to travel such questions as how we might describe what we have never seen before or what helps us to see more clearly or persuades us to see what's not there. Art, science, vision and memory inform one another in this original and illuminating work.

Ans Westra: A life in photography by Paul Moon $50

In a career that spanned six decades, the Dutch-Kiwi photographer Ans Westra (1936–2023) made it her life’s work to capture the growth of a nation through hundreds of thousands of images. Her photographic catalogue is now widely thought of as a photo album of Aotearoa New Zealand. This richly illustrated biography interrogates her remarkable — and at times controversial — practice, and a life that always put photography first.

Verdigris by Michele Mari (translated from Italian by Brian Robert Moore) $35

At the tail end of the 1960s, the thirteen-year-old Michelino spends his summers at his grandparents' modest estate in Nasca, near Lake Maggiore, losing himself in the tales of horror, adventure, and mystery shelved in his grandfather's library. The greatest mystery he's ever encountered, however, doesn't come from a book — it's the groundskeeper, Felice, a sometimes frightening, sometimes gentle, always colourful man of uncertain age who speaks an enchanting dialect and whose memory gets worse with each passing day. When Michelino volunteers to help the old man by providing him with clever mnemonic devices to keep his memory alive, the boy soon finds himself obsessed with piecing together the eerie hodgepodge of Felice's biography — a quest that leads to the uncovering of skeletons in Nazi uniforms in the attic, to Felice's admission that he can hear the voices of the dead, and to a new perspective on Felice's endless war against the insatiable local slugs, who are by no means merely a horticultural threat. And yet nothing could be more fascinating to Michelino than Felice's own secret origins. Where did he come from? Is he the victim or the villain of his story? Is he a noble hero, a holy fool, or perhaps the very thing that Michelino most wants and fears: a real-life monster.

”A gripping, beguiling, occasionally discomfiting, and utterly fascinating tour de force.” —Kirkus

Orbital by Samantha Harvey $40

A team of astronauts in the International Space Station collect meteorological data, conduct scientific experiments and test the limits of the human body. But mostly they observe. Together they watch their silent blue planet, circling it sixteen times, spinning past continents and cycling through seasons, taking in glaciers and deserts, the peaks of mountains and the swells of oceans. Endless shows of spectacular beauty witnessed in a single day. Yet although separated from the world they cannot escape its constant pull. News reaches them of the death of a mother, and with it comes thoughts of returning home. They look on as a typhoon gathers over an island and people they love, in awe of its magnificence and fearful of its destruction. The fragility of human life fills their conversations, their fears, their dreams. So far from earth, they have never felt more part — or protective — of it. They begin to ask, what is life without earth? What is earth without humanity?

”Beautiful in every aspect.” —Sarah Moss

”One of the most beautiful novels I have read in a very long time.” —Mark Haddon

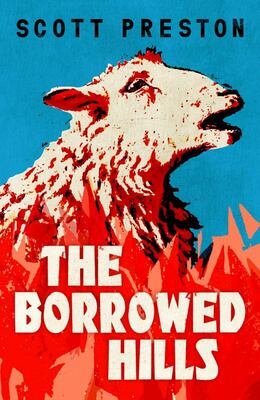

The Borrowed Hills by Scott Preston $38

As foot and mouth disease spreads across the hills of Cumbria, emptying the valleys of sheep and filling the skies with smoke, Steve Elliman and William Herne, two neighbouring farmers, join forces to reverse their fortunes by rustling livestock from the south. With the struggles of the land never far away, Steve's only distraction is his growing fascination with William's wife, Helen. When their mountain home comes under the sway of a ruthless outsider, it is left to Steve to save himself and what's left of their farming community, in a savage conflict that threatens an ancient way of life. A reimagining of the American Western for the fells of northern England, Scott Preston's thrilling debut tells of men and women battered by circumstance, struggling to make lives for themselves in an unyielding land. Lyrical, cinematic, visceral and steeped in local folklore, The Borrowed Hills is an epic tale of a forgotten Britain.

”Preston's blistering tale of land and violence is written in his distinctive Cumbrian voice, a vernacular stripped to its bones that encompasses stark prose and sudden startling flashes of poetry. The result is half Tarantino and half pitch-black northern realism that slides under the skin and lodges deep. A sucker-punch of a novel, edged with knife-sharp black humour and shot through with moments of startling beauty.” —Guardian

”Scott Preston lifts the veil from the picture-postcard beauty of Britain's Cumbrian fells to expose an atmosphere of festering despair in the lives of two farmers who lose everything when their sheep are destroyed by the government in order to contain an outbreak of Foot and Mouth disease. When they take desperate measures to rebuild their shattered world, what happens feels tragically inevitable. The Borrowed Hills is a story of anger and violence, devotion, love, and back-breaking hard work, told with dark, dead-pan humour and a rough kind of poetry.” —Carys Davies

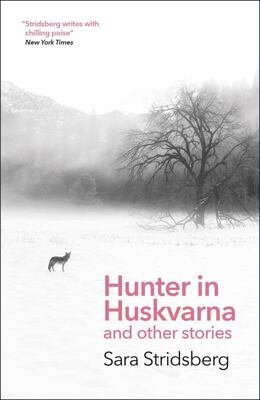

Hunter in Huskvarna by Sara Stridsberg (translated from Swedish by Deborah Bragan-Turner) $28

A young woman becomes obsessed with her psychoanalyst's daughter. A police officer's mistress clandestinely cares for his dying wife. A boy goes missing from the Swedish town of Huskvarna after he was last seen walking with a wolf. From the inside of a dead whale's belly, to an industrial town emptied out after its factory's closure, to a Texan prison where a young man visits his sister's murderer on death row, Stridsberg approaches both the strange and the mundane with a fairy-tale sensibility that lights our world anew.

Time runs through this collection like water, variously ebbing, flowing and rippling beneath the shimmering surface of Stridsberg's prose. These genre-spanning stories are held together by a sense of longing: for escape from the narrow margins of a prescribed life, for a past which promises an undiscovered future, for a place or a person that feels like home.

”There's a dreamy quality to these death-stalked tales from Swedish author Stridsberg, which marry old-world mysteriousness to modern sensibilities.” —Daily Mail

Giacometti in Paris by Michael Peppiatt $65

Today the work of Alberto Giacometti is world-famous and his sculptures sell for record-breaking prices. But from his early days as an unknown outsider to the end of a dramatic international career, Giacometti lived in the same hovel of a studio in Paris. Arriving in Paris from the Swiss Alps in 1922, Giacometti was shaped not only by his relationships with artists and writers — from Picasso, Breton and Dali to Sartre, Beauvoir and Beckett — but by the everyday life, pre-war and post-war, of Paris itself. His distinctive figures emerged from the city's unique atmosphere: the crumbling grey stone of its humbler streets and the cafe-terraces buzzing with ideas and gossip. In Giacometti in Paris, Michael Peppiatt, who spent thirty years documenting the Parisian art world and mixing with many of the people Giacometti knew, charts the course of the artist's life and work. From falling in and out with the Surrealists to years of artistic anguish, from devotion to his mother to intense friendships, tragic love affairs and a fraught marriage, this is an intimate portrait of an artist in exceptional times.

”Marvellous, intimate and insightful. It reads like a novel by Samuel Beckett.” —Paul Theroux

We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian memoir by Raja Shehadeh $25

A subtle psychological portrait of the author's relationship with his father during the twentieth-century battle for Palestinian human rights. Aziz Shehadeh was many things: lawyer, activist, and political detainee, he was also the father of bestselling author and activist Raja. In this new and searingly personal memoir, Raja Shehadeh unpicks the snags and complexities of their relationship. A vocal and fearless opponent, Aziz resists under the British mandatory period, then under Jordan, and, finally, under Israel. As a young man, Raja fails to recognize his father's courage and, in turn, his father does not appreciate Raja's own efforts in campaigning for Palestinian human rights. When Aziz is murdered in 1985, it changes Raja irrevocably. This is not only the story of the battle against the various oppressors of the Palestinians, but a moving portrait of a particular father and son relationship. Now in paperback.

”It's a mark of Shehadeh's brilliance that this latest revisiting is full of surprises: it's even in tone, but jet-fuelled by implicit emotion; there's no conventional suspense, but it is absolutely gripping.” —Rachel Aspden

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray $26

The Barnes family is in trouble. Dickie's once-lucrative car dealership is going under, and while his wife is frantically selling off her jewellery on eBay, he's busy building an apocalypse-proof bunker in the woods. Meanwhile their teenage daughter is veering off the rails, in thrall to a toxic friendship, and her little brother is falling into the black hole of the internet... Where did it all go wrong? The present is in crisis but the causes lie deep in the past. How long can this unhappy family wait before they have to face the truth? And if the story has already been written, is there still time to find a happy ending? Shortlisted for the 2023 Booker Prize. New, cheaper, smaller edition.

”It can't be overstated how purely pleasurable The Bee Sting is to read. Murray's brilliant novel, about a rural Irish clan, posits the author as Dublin's answer to Jonathan Franzen. A 650-page slab of compulsive high-grade entertainment, The Bee Sting oozes pathos while being very funny to boot. Murray's observational gifts and A-game phrase-making render almost every page — every line, it sometimes seems — abuzz with fresh and funny insights. At its core this is a novel concerned with the ties that bind, secrets and lies, love and loss. They're all here, brought to life with captivating vigour in a first-class performance to cherish.” —Anthony Cummins, Observer

First Things: A memoir by Harry Ricketts $35

In First Things, poet Harry Ricketts chronicles his early life through the lens of ‘firsts’: those moments that can hold their detail and potency across a lifetime. Set mostly in Hong Kong and Oxford, these bright fragments include the places, people, writers, encounters and obsessions that have shaped Ricketts’ world, from his first friends and rivals to his first time being caned by a teacher and his first time dropping acid. There are other, more enigmatic firsts here too, like the first time he realised what really mattered, and the first time he began doubting God. Who really were we, back then? Which parts of ourselves get to be remembered and carried along with us, and which parts are gone forever? In First Things, the gaps in between shine as brightly as the memories themselves.

Alexandria: The city that changed the world by Islam Issa $60

A city drawn in sand. Inspired by the tales of Homer and his own ambitions of empire, Alexander the Great sketched the idea of a city onto the sparsely populated Egyptian coastline. He did not live to see Alexandria built, but his vision of a sparkling metropolis that celebrated learning and diversity was swiftly realised and still stands today. Situated on the cusp of Africa, Europe and Asia, great civilisations met in Alexandria. Together, Greeks and Egyptians, Romans and Jews created a global knowledge capital of enormous influence: the inventive collaboration of its citizens shaped modern philosophy, science, religion and more. In pitched battles, later empires, from the Arabs and Ottomans to the French and British, laid claim to the city but its independent spirit endures. In this sweeping biography of the great city, Islam Issa takes us on a journey across millennia, rich in big ideas, brutal tragedies and distinctive characters, from Cleopatra to Napoleon. From its humble origins to dizzy heights and present-day strife, Alexandria tells the gripping story of a city that has shaped our modern world.

”In Islam Issa's monumental and vividly imagined new tale of the city, Alexandria comes to life. Issa's Alexandria arrives at 2011's Arab Spring having covered more than two millennia in just over 400 pages — no mean feat. But his real success is the book's sense of personality. It ends with Issa walking through the modern city that now stands on the ancient site, passing its markets and Art Deco cinemas. He writes about the present as vividly as the storied past. This book is a fitting tribute to a city that has survived, changed and grown for so many centuries.” —Francesca Peacock, Daily Telegraph

Sociopath: A memoir by Patric Gagne $40

“Your friends would probably describe me as nice. But guess what? I can't stand your friends. I'm a liar. I'm a thief. I'm highly manipulative. I don't care what other people think. I'm capable of almost anything.” Sociopath: A Memoir is at once a mesmerising tale of a life lived on the edge of the law, a redemptive love story and a moving account of one woman's battle to create a place for herself and the 5% of the population who are also — like her — sociopaths. Ever since she was a small child, Patric Gagne knew she was different. Although she felt intense love for her family and her best friend, David, these connections were never enough to make her be 'good', or to reduce her feelings of apathy and frustration. As she grew older, her behaviour escalated from petty theft through to breaking and entering, stalking, and worse. As an adult, Patric realized that she was a sociopath. Although she instantly connected with the official descriptions of sociopathy, she also knew they didn't tell the full story: she had a plan for her life, had nurtured close relationships and was doing her best (most of the time) to avoid harming others. As her darker impulses warred against her attempts to live a settled, loving life with her partner, Patric began to wonder — was there a way for sociopaths to integrate happily into society? And could she find it before her own behaviour went a step too far? Interesting.

Air Conditioning (‘Object Lessons’ series) by Hsuan L. Hsu $23

Air conditioning aspires to be unnoticed. Yet, by manipulating the air around us, it quietly conditions the baseline conditions of our physical, mental, and emotional experience. From offices and libraries to contemporary art museums and shopping malls, climate control systems shore up the fantasy of a comfortable, self-contained body that does not have to reckon with temperature. At the same time that air conditioning makes temperature a non-issue in (some) people's daily lives, thermoception or the sensory perception of temperature is being carefully studied and exploited as a tool of marketing, social control, and labor management. Yet air conditioning isn't for everybody — its reliance on carbon fuels divides the world into habitable, climate-controlled bubbles and increasingly uninhabitable environments where AC is unavailable. Hsuan Hsu's Air Conditioning explores questions about culture, ethics, ecology, and social justice raised by the history and uneven distribution of climate controlling technologies.

”A cool blast of discomforting brilliance, Air Conditioning examines the conditioning of our indoor and interior climates of work, domesticity, and consumption. It is not inward looking to the sealed boxes and bubbles of air-conditioned detachment, but focused on the complex exchanges and inequalities involved in sustaining comfortable places, cooled bodies and technologies by making other places, and other (often poor and racialised) lives, uncomfortable and unliveable. Hsu's book hums, ventilating ideas in an insistent, vital tone to show how this ordinary object, submerged within walls and behind vents, has mattered so much to us.” —Peter Adey, Royal Holloway University of London

Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop by Hwang Bo-reum (translated from Korean by Shanna Tan) $37

Yeongju did everything she was supposed to, go to university, marry a decent man, get a respectable job. Then it all fell apart. Burned out, Yeongju abandons her old life, quits her high-flying career, and follows her dream. She opens a bookshop. In a quaint neighbourhood in Seoul, surrounded by books, Yeongju and her customers take refuge. From the lonely barista to the unhappily married coffee roaster, and the writer who sees something special in Yeongju — they all have disappointments in their past. The Hyunam-dong Bookshop becomes the place where they all learn how to truly live.

A selection of books from our shelves.

Click through to find out more:

Some superb books have been recognised in this year’s awards, from a strong year of Aotearoa publishing. Read the judges’ comments below, and click through to our website for your copies.

JANN MEDLICOTT ACORN PRIZE FOR FICTION

Lioness by Emily Perkins (Bloomsbury Publishing) $25

A searing and urgent novel crackling with tension and intelligence, Lioness starts with a hiss and ends with a roar as protagonist Therese’s dawning awareness and growing rage reveals itself. At first glance this is a psychological thriller about a privileged wealthy family and its unravelling. Look closer and it is an incisive exploration of wealth, power, class, female rage, and the search for authenticity. Emily Perkins deftly wrangles a large cast of characters in vivid technicolour, giving each their moment in the sun, while dexterously weaving together multiple plotlines. Her acute observations and razor-sharp wit decimate the tropes of mid-life in moments of pure prose brilliance, leaving the reader gasping for more. Disturbing, deep, smart, and funny as hell, Lioness is unforgettable.

MARY AND PETER BIGGS AWARD FOR POETRY

Chinese Fish by Grace Yee (Giramondo Publishing) $30

Grace Yee’s is a striking aesthetic – it blurs genres, it dances around the page, it crosses languages by fusing Cantonese-Taishanese and English, both official and unofficial. Her craft is remarkable. She moves between old newspaper cuttings, advertisements, letters, recipes, cultural theory, and dialogue. Creating a new archival poetics for the Chinese trans-Tasman diaspora, the sequence narrates a Hong Kong family’s assimilation into New Zealand life from the 1960s to the 1980s, interrogating ideas of citizenship and national identity. It displaces the reader, evoking the unsettledness of migration. In Chinese Fish, Yee cooks up a rich variety of poetic material into a book that is special and strange; this is poetry at its urgent and thrilling best.

BOOKSELLERS AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND AWARD FOR ILLUSTRATED NON-FICTION

Don Binney — Flight Path by Gregory O’Brien (Auckland University press) $90

Even as an experienced biographer, Gregory O’Brien has achieved a near impossible task in Don Binney: Flight Path. He has encapsulated the artist’s full life, honestly portraying his often contrary personality, and carefully interrogating a formidably large body of work and its place in Aotearoa New Zealand’s art history. O’Brien’s respect for Binney includes acknowledging that he could be both charming and curmudgeonly, and as a result he offers a complete picture of this complex and creative man. Equally compelling are the book’s faithfully reproduced artworks, exemplifying the best in design, layout and reproduction. From the cover onwards, the images of the paintings take us to the place where Binney observed the land and the birds, capturing the qualities of whenua that meant so much to him.

GENERAL NON-FICTION AWARD

An Indigenous Ocean: Pacific essays by Damon Salesa (Bridget Williams Books) $50

In An Indigenous Ocean, Toeolesulusulu Damon Salesa weaves together academic rigour, captivating stories and engaging prose to reframe our understanding of New Zealand’s colonial history in the South Pacific. This scholarly but highly accessible collection of essays carves out space for indigenous voices to tell their own narratives. Grounded in a deep understanding of Pacific history and cultures, Salesa addresses the contemporary social, political, economic, regional and international issues faced by Pacific nations. This seminal work asserts the Pacific’s ongoing impact worldwide, despite marginalisation by New Zealand and others, and will maintain its relevance for generations.

MŪRAU O TE TUHI – MĀORI LANGUAGE AWARD

Te Rautakitahi o Tūhoe ki Ōrākau by Tā Pou Temara (Ngāi Tūhoe) (Kotahi Rau Pukapuka, Auckland University Press) $40

He motuhenga marika tēnei pukapuka inā hoki ko tāu e pānui ana ko ngā kupu tuku iho a ngā tūpuna ake o te kaituhi i rongo rā i ngā kōrero a ētehi o te rautakitahi a Tūhoe i haere rā ki te tinei i te ahi ki tawhiti, koia te pakanga rongonui o Ōrākau. Hihiri ana a Hinengaro i a Tā Pou Temara e taki ana i ngā kōrero tuku iho, me te aha he mea kōrero ki te reo o Tūhoe koinei te reo i tupu ai ia. Tuituia ana e ia ōna ake whakaaro puta noa i te pukapuka kia noho mai ko tētehi pukapuka kounga nei mā te hunga e pīkoko ki te reo me te kaihītori ā-kāinga e kai ngākau ana i ngā kōrero o Ngā Riri Whenua o Aotearoa.

This book is truly unique, in that what you read are the narratives which have been handed down to the author through his grandparents, who heard the accounts from that very brave band of Te Urewera and Ngāi Tūhoe who travelled to extinguish the fires from afar at the famous Battle of Ōrākau. Tā Pou Temara enriches us with not only their stories but also a retelling of their narratives in the language of Tūhoe, the language he grew up in. He weaves his own thoughts through the book, which makes it a valuable read for both lovers of the Māori language and at-home-historians interested in the New Zealand Land Wars.

MĀTĀTUHI FUNDATION BEST FIRST BOOK AWARDS

HUBERT CHURCH PRIZE FOR FICTION

Ruin, And other stories by Emma Hislop (Te Herenga Waka University Press) $35

Each story in this powerful collection exhibits an artful control of situation, character, and language to examine the fallout of painful events which largely occur offstage. Emma Hislop’s portrayals are perceptive, providing the women in her stories the space to grapple with disquieting questions that lack easy answers, while the insistent humanity of her characterisations suggests cause for hope. There is not a spare word in these refined and compelling stories, which introduce a striking new voice to our literature.

E.H. MCCORMICK PRIZE FOR GENERAL NON-FICTION

There’s a Cure for This by Emma Wehipeihana (Ngāti Tukorehe, Ngāti Porou) (Penguin Books) $35

Emma Wehipeihana’s engaging, eloquent, witty and sometimes confronting memoir is an extremely impressive first book. It is structured as a series of powerful essays about her journey as a wahine Māori through both her early life and her time in medical school. Emerging as a doctor, she recounts with candour and wry humour the racism she and other Māori experience, and she highlights, in an infinitely readable way, the structural inequalities in the health system.

JESSIE MACKAY PRIZE FOR POETRY

At the Point of Seeing by Megan Kitching (Otago University Press) $25

At the Point of Seeing is one of the most accomplished debuts readers are likely to encounter. The collection uses structure to amplify meaning, and its luxuriant lexicon and sometimes knotty syntax are always invigorating rather than confusing. But this book is never a mere exercise in building poems mechanically. Megan Kitching’s poems are warm-blooded, compassionate, and inquiring. They take the reader into an Aotearoa landscape and a moral universe that they will want to explore over and over again.

JUDITH BINNEY PRIZE FOR ILLUSTRATED NON-FICTION

Rugby League in New Zealand: A people’s history by Ryan Bodman (Bridget Williams Books) $60

You don’t have to have seen a rugby league game, or even like sport, to be enchanted by Ryan Bodman’s debut book. This is a meticulously researched and engagingly written social history, packed full of stories about what rugby league has meant not just to the players and their supporters, but also to entire communities. The photographs – showing crowd support, action shots, smiling children, and female players – give us a fascinating insight into the story of the sport, whether on the margins or in the mainstream.

Read our latest newsletter.

Find out (among other things) what you’ll be reading next.

10 May 2024

The Other Name (Septology I—II) by Jon Fosse (translated from Nynorsk by Damion Searle)

and I see myself sitting and reading the thick book, and I have reached that point in the book, though it is not in fact a point in the book for there is nothing in the book that would mark such a point, but rather a point in my reading of the book, which just happens to be around page seventy-five, that I come to realise that the book is written entirely in one sentence, one slow, patient, uninterrupted flow of words, no, I think, that is not correct, the book is written in two parts, though each begins with the word And, but neither part ends, each rather just leaves off, so it would not be correct that the book is written in one sentence, or in two sentences, one for each part, but rather in no sentences, one, or two, slow, patient, uninterrupted flow, or flows, of words, that much at least I got right, I think, just the kind of thing I like, but done with such virtuosity and with such little display of virtuosity that I had not realised until page seventy-five or thereabouts that there are no full stops to be found in this book, or no full stop, I am uncertain if this absence should be singular or plural, possibly both, this Jon Fosse and his translator Damion Searls having built these words without one misstep, or missomething, the metaphor seems mixed and I has not even realised that it was a metaphor, I must be more careful, capturing the flow of thought, so to call it, and speech, realistically, seemingly of the narrator, a middle-aged painter named Asle, living, I am almost tempted to put, as such people do, in a small town in western Norway, driving in the snow to and from a city on the western coast of Norway, the city of the gallery which shows, which is a euphemism of sorts for sells, his paintings, but also the city in which lives a middle-aged painter named Asle, resembling both in looks and clothing, if clothing is not part of looks, the narrator, the narrator narrating in the first person and this other Asle, the alter-Asle if you like, this alter-Asle to the thoughts and memories of whom the narrator-Asle has extraordinary access, though there is no evidence of any reciprocal mechanism, we are, I am sure, never given an instance of the alter-Asle even being aware of the existence of such a person as the narrator, this aler-Asle, being confined to the third person, and, I wonder, what sort of trauma confines a person to an existence only in the third person, presumably a trauma, I think, this alter-Asle being also an alcoholic and a person who “most of the time, doesn’t want to live any more, he’s always thinking that he should go out into the sea, disappear into the waves,” but not doing so because of his love for his dog, there is, I think as I am reading, some relationship between the two Asles, well, obviously there is, my thought, or the thought I have, being that the alter-Asle is the actual Asle and the narrator-Asle is the Asle that the alter-Asle-who-is-actually-the-actual-Alse would have been if he was not the Asle he became, which, I think, I have made sound a bit confusing, and the opposite of an explanation, not that that matters, on account of whatever trauma, or whatever it is that I speculate is a trauma, that confined him to a third-person existence, the characters being one character, all characters being one character as they are in all books, I speculate, though in this book almost all the characters have, if not the same name, almost the same name, which tightens the knot somewhat, if I can be forgiven another metaphor, though I will not forgive myself for it at least, I will try to avoid, I think, thinking of the relationships between these persons-who-are-one-person, or, in any rate, describing the relationships between these persons-who-are-one-person, in any way other than a literary way, whatever that means, nothing, I think, the person that Asle could have been sees the Asle that Asle became, though Alse cannot know him, the person that Asle could have been rescues Asle when he has collapsed in the snow and takes him to the Clinic and to the Hospital, and takes the dog to look after, who knows, though, if the third-person Asle, the one I was calling the alter-Asle until that became too confusing, at least for me, survives, neither we nor the first-person Asle know that, but after the first-person Asle goes to the city and rescues the third-person Asle from the snowdrift, how could he know where to find him, I wonder, he begins, in the second part of the book, to have access to some deeply buried memories of the Asle that perhaps they once both were, memories all in the third person, for safety, I think, memories firstly of Asle’s and his sister’s disobedience of their parents in straying along the shore and to the nearby settlement, a narrative in which threat hums in every detail, a narrative in which colour impresses itself so deeply upon Asle that, I think, he could have become nothing other than a painter, a narrative that seems searching for a trauma, for a misfortune, a narrative assailed by an inexplicable motor noise as they approach the settlement but which resolves with a misfortune that is anticlimactic, at least for Asle, a trauma but not his trauma, what has this narrative avoided, I wonder at this point, what has not been released, or what has not yet been released, I wonder, Fosse is a writer who writes to be rid of his thoughts, I think, just as his narrator says, “when I paint it’s always as if I’m trying to paint away the pictures stuck inside me, to get rid of them in a way, to be done with them, I have all these pictures inside me, yes, so many pictures that they’re a kind of agony, I try to paint away these pictures that are lodged inside me, there’s nothing to do but paint them away,” and, yes, when the narrator lies in bed at the end of the second part of the book and is unable to sleep, he does recover the memory, a third person memory, the memory of the trauma that split the Asles and trapped one thereafter in the third person, the memory that explains the awful motor noise that intruded on the previous narrative of disobedience as the children approached the locus of the trauma, and, I think, all the sadness of the book leads from here and to here, and after that to go on

Everyone needs to brave sometimes. Rebecca would rather be invisible. Looking down seems a good option. In Jane Arthur’s Brown Bird, we meet the kind and quiet Rebecca. She’s eleven, an excellent baker, and loves to have her head buried in a book. It’s the holidays and her plans are about to be disrupted by the whirlwind called Chester. What will Rebecca find out about herself, and is Chester as carefree as he seems? Jane Arthur, award-winning poet, perfectly captures the voice of eleven-year-old Rebecca, and expresses the uncertainties, awkwardnesses and hopes that we all experience, in her debut children’s book.

Rebecca is the best timid character to grab my attention this year, and Jane Arthur’s Brown Bird has flown straight to a VOLUME Favourite. Why? One: there’s a map! For me, it was reminiscent of my childhood readings and rereadings of Milly Molly Mandy — I loved those maps showing the village (despite being a million miles away from my childhood experience in Aotearoa — no thatched roofs in any direction). This map is more akin to the small avenue of my childhood. Brown Bird takes place on Mount Street — a small no exit of twelve houses. And each of these houses and their inhabitants will have a part to play. Two: there’s the wonderful Rebecca and the delightful Chester. Rebecca doesn’t like to be noticed and her preference for an excellent day is reading and baking. She’s a whizz at both. The school holidays mean Mum’s at work a lot, and Rebecca visits Tilly, their neighbour. Rebecca has it all planned. She’s got her stack of books ready to go. But then there’s Chester. A ball of energy that disrupts her calm (not that she is really calm — in fact, she’s often quite anxious and overly aware of her surroundings). And Chester has a plan. A plan that involves knocking on doors, meeting people and offering their services doing odd jobs. To Rebecca, Chester doesn’t have a care in the world and is all exuberance. It’s exhausting, nerve-wracking but also exhilarating. Three: Brown Bird is a story about friendship. Chester isn’t like her, but for the first time since they moved to their new place, Rebecca has a friend. They sleep in the tent, eat treats and laugh, but also disagree and work out what’s important. Chester may be full of vim, but his life is far from plain sailing. Four: It’s a spot on depiction of that moment in childhood — Rebecca is eleven — when things change, emotionally and physically. Rebecca’s anxiety and frustration is all there and well articulated, but so too is her kindness and tenacity. She’s the perfect companion for anyone who feels awkwardly at odds with the world. Five: I love the quietness of Brown Bird. It’s a book that draws you in (without shouting you into the action or screaming nonsense), lets you think, and also makes you smile. It’s warm-hearted and you’ll be backing Rebecca and Chester to be the lovely and brave humans they are. Six: It’s also sweetly written. You’re in the story before you know it, and Arthur has a knack for quirky humour popping up in just the right places, alongside the more daunting prospects for the protagonists, as well as feeding in issues of diversity and difference without being heavy handed. Highly recommended for 9+. Excellent for anyone who’s taken a while to believe in themselves. Here’s hoping we meet Rebecca again.

These books have just arrived!

Click through to our website for your copies:

Hine Toa: A story of bravery by Ngāhuia te Awekōtuku $40

A memoir by a trailblazing voice in women's, queer and Māori liberation movements. In the 1950s, a young Ngāhuia is fostered by a family who believe in hard work and community. Although close to her kuia, she craves more: she wants higher education and refined living. But whanau dismiss her dreams. To them, she is just a show-off, always getting into trouble, talking back and running away. In this fiery memoir about identity and belonging, Ngahuia te Awekotuku describes what was possible for a restless working-class girl from the pa. After moving to Auckland for university, Ngahuia advocates resistance as a founding member of Nga Tamatoa and the Women's and Gay Liberation movements, becoming a critical voice in protests from Waitangi to the streets of Wellington.

”Remarkable. At once heartbreaking and triumphant.” —Patricia Grace

”Brilliant. This timely coming-of-age memoir by an iconic activist will rouse the rebel in us all. I loved it.” —Tina Makereti

Julia by Sandra Newman $37

London, chief city of Airstrip One, the third most populous province of Oceania. It's 1984 and Julia Worthing works as a mechanic fixing the novel-writing machines in the Fiction Department at the Ministry of Truth. Under the ideology of IngSoc and the rule of the Party and its leader Big Brother, Julia is a model citizen - cheerfully cynical, believing in nothing and caring not at all about politics. She routinely breaks the rules but also collaborates with the regime whenever necessary. Everyone likes Julia. A diligent member of the Junior Anti-Sex League (though she is secretly promiscuous) she knows how to survive in a world of constant surveillance, Thought Police, Newspeak, Doublethink, child spies and the black markets of the prole neighbourhoods. She's very good at staying alive. But Julia becomes intrigued by a colleague from the Records Department — a mid-level worker of the Outer Party called Winston Smith — when she sees him locking eyes with a superior from the Inner Party at the Two Minutes Hate. And when one day, finding herself walking toward Winston, she impulsively hands him a note — a potentially suicidal gesture — she comes to realise that she's losing her grip and can no longer safely navigate her world. Newman’s feminist narrative stands in parallel to Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and is full of comtemporary resonance and urgency.

”Sandra Newman's Julia, approved by Orwell's estate, is neither an anachronistic betrayal of the source material, nor some parched scholarly exercise. Rather, it is a vibrant, full-blooded book that adheres to the spirit of the original while tearing elements of it — namely the character of Winston Smith — to pieces. It is very funny, peppered with fresh observations that made me laugh out loud. Newman hits all the big beats from Orwell's book — the torture in Room 101, Julia and Winston's final meeting, but what is so wonderful about this is not just its depiction of Julia as even cleverer than you might imagine, but also its rich understanding of what Orwell meant about society's three strata locked in an endless battle for supremacy. Julia, living in this pressure cooker, is often cruel as well as astute. She is the one in the end who understands this.” —I Paper

”Julia's story is so well engineered it perfectly matches the contours of Nineteen Eighty-Four. The same goes for Newman's dialogue and descriptive language, both of which have an Orwellian melody. This is a good book, which offers an optimistic take on the pessimistic original.” —Irish Independent

Hagstone by Sinéad Gleeson $37

The sea is steady for now. The land readies itself. What can be done with the woman on the cliff? On a wild and rugged island cut off and isolated to some, artist Nell feels the island is her home. It is the source of inspiration for her art, rooted in landscape, folklore and ‘the feminine’. The mysterious Inions, a commune of women who have travelled there from all over the world, consider it a place of refuge and safety, of solace in nature. All the islanders live alongside the strange murmurings that seem to emanate from within the depths of the island, a sound that is almost supernatural — a Summoning as the Inions call it. One day, a letter arrives at Nell's door from the reclusive Inions who invite Nell into the commune for a commission to produce a magnificent art piece to celebrate their long history. In its creation, Nell will discover things about the community and about herself that will challenge everything she thought she knew.

The Hearing Test by Eliza Barry Callahan $38

An artist in her late twenties awakens one morning to a deep drone in her right ear. She is diagnosed with Sudden Deafness, but is offered no explanation for its cause. As the spectre of total deafness looms, she keeps a record of her year — a score of estrangement and enchantment, of luck and loneliness, of the chance occurrences to which she becomes attuned — while living alone in a New York City studio apartment with her dog. Through a series of fleeting and often humorous encounters — with neighbours, an ex-lover, doctors, strangers, family members, faraway friends, and with the lives and works of artists, filmmakers, musicians, and philosophers — making meaning becomes a form of consolation and curiosity, a form of survival. At once a rumination on silence and a novel on seeing, The Hearing Test is a work of vitalising intellect and playfulness which marks the arrival of a major new literary writer with a rare command of form, compression, and intent.

”A young woman's sudden hearing loss initiates and propels The Hearing Test. But affliction is also a catalyst for the many irresistible twists and digressions that make this novel of derive so compelling. Callahan never explains; with steely reserve she observes and chronicles, makes ingenious, delirious connections and transitions, and takes us on a journey through her cultural mindscape of artists, writers, cinema and music, offering it up with muted irony and a limpid grace. The Hearing Test is ecstatic prose.” —Moyra Davey

”Eerie and tender and utterly consuming, The Hearing Test has built an entirely new world from the materials of the one we know. It takes you to a restaurant called the void, Il Vuoto, and serves you its primal, beguiling sustenance: a nourishment of pauses, estrangement, and bewilderment. The voice here is wise and wry and wondering; in its fresh and faltering silences are frequencies I've never heard before. From the first paragraph, I knew I wanted to keep reading Eliza Barry Callahan forever.” —Leslie Jamison

”A composer suffering from sudden hearing loss finds herself even more sensitive to the lives of others, observing neighbors and the absurdities of the city, always punctuated by art and literary gossip. This debut work by Eliza Callahan is an extraordinary piece of literature, to be read alongside the novels of W.G. Sebald, Rachel Cusk, and Maria Gainza.” —Kate Zambreno

Feedback: Uncovering the hidden connections between life and the universe by Nicholas R. Golledge $60

We live in a world where things come and go, rise and fall, grow and decay, tracing out cycles of change that are ordered and predictable. But amongst those well-behaved rhythms hide other phenomena, pulsing and fizzing and refusing to play by the same rules. Earth and the life upon it have evolved over billions of years to be right where we are now only because of feedbacks that pushed those systems until they broke. And then those systems adapted, reorganized, and rebuilt. With each new cycle of growth it was feedbacks that created order from disorder and gave rise to a world perfectly optimized for everything it needed to be. Now the latest scientific research is revealing that the exact same patterns that describe plate tectonics, evolution, and mass extinctions also emerge in the heartbeat of our everyday lives, underpinning everything from the cohesion of our social networks and personal relationships to our emotional well-being and spiritual beliefs. In Feedback, we embark on a backstage journey revealing how these lesser-known processes keep us operating right where we need to be, poised at the edge of chaos. In a world simultaneously threatened with social and environmental disasters this journey uncovers the hidden connections that unite us not just to those around us but also across vast scales of time and space to the very fabric of the universe. An important book from a Pōneke climate scientist.

”Left me fizzing with the joy of being alive.” —Rebecca Priestley

I Must Be Dreaming by Roz Chast $50

New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast's new graphic narrative, explores the surreal nighttime world inside her mind — and untangles (or retangles) one of our most enduring human mysteries: dreams. Ancient Greeks, modern seers, Freud, Jung, neurologists, poets, artists, shamans — humanity has never ceased trying to decipher one of the strangest unexplained phenomena we all experience: dreaming. In her new book, Roz Chast illustrates her own dream world, a place that is sometimes creepy but always hilarious, accompanied by an illustrated tour through ‘Dream-Theory Land’ guided by insights from poets, philosophers, and psychoanalysts. Illuminating, surprising, funny, and often profound. Recommended!

Pencil by Carol Beggy $23

A cylinder of baked graphite and clay in a wood case, the pencil creates as it is being destroyed. To love a pencil is to use it, to sharpen it, and to essentially destroy it. Pencils were used to sketch civilization's greatest works of art. Pencils were there marking the choices in the earliest democratic elections. Even when used haphazardly to mark out where a saw's blade should make a cut, a pencil is creating. Pencil offers a deep look at this common, almost ubiquitous, object. Pencils are a simple device that are deceptively difficult to manufacture. At a time when many use cellphones as banking branches and instructors reach students online throughout the world, pencil use has not waned, with tens of millions being made and used annually.

The Morningside by Téa Obreht $40

There's the world you can see. And then there's the one you can't. Welcome to The Morningside. Silvia feels unmoored in her new life because her mother has been so diligently secretive about their family's past. Silvia knows almost nothing about the place she was born and spent her early years; nor does she know why she and her mother had to leave. But in Ena there is an opening: a person willing to give a young girl glimpses into the folktales of her demolished homeland, a place of natural beauty and communal spirit that is lacking in Silvia's lonely and impoverished reality. Enchanted by Ena's stories, Silvia begins seeing the world with magical possibilities, and becomes obsessed with the mysterious older woman who lives in the penthouse of the Morningside. Bezi Duras is an enigma to everyone in the building; she has her own elevator entrance, and only leaves to go out at night and walk her three massive hounds, often not returning until the early morning. Silvia's mission to unravel the truth about this woman's life, and her own haunted past, may end up costing her everything.

”Obreht is a novelist of great skill and warmth, for whom the ancient forms of storytelling — folk tales, myths and legends — retain all their capacity to explain and mystify, soothe and terrify. Though The Morningside could be called dystopian, to this reader it feels hopeful in the way it imagines the near future. It is more about the ways we pull together than the ways we fall apart.” —Guardian

The St Ives Artists: A biography of time and place by Michael Bird $75

The flourishing of international modernism in Cornwall was a unique episode in the story of modern art in Britain. No other small seaside town has been host to such a roll-call of major artists. Weaving in-depth research into a narrative of 'startling anecdotal richness', Michael Bird explores the many — often unexpected — connections between St Ives artists and broader currents in 20th-century British history. He sets the careers of international artists such as Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Patrick Heron and Peter Lanyon in the context of a local environment that held powerful meanings for their work.

Bird examines the influence of the two world wars, the birth of the Welfare State and the Cold War, the space race of the 1960s — all of which found echoes in artists' work — as well as the position of women artists in St Ives, the role of social class, and relations between artists and the community. The artists themselves emerge as vivid personalities. Do Alfred Wallis, Naum Gabo, Bernard Leach and Roger Hilton really have anything in common? The answers Michael Bird uncovers add up to a fascinating and highly readable account of the St Ives phenomenon. A new edition of this superb book.

Ora — Healing Ourselves: Indigenous knowledge, healing, and wellbeing edited by Leonie Pihama and Linda Tuhiwai Smith $65

This collection brings together indigenous thinkers and practitioners from Aotearoa and internationally to discuss the effects of trauma on indigenous peoples across social, economic, political and cultural environments. The authors explore understandings and practices of indigenous people, grounded in the knowledge of ancestors and based on research, that facilitate healing and wellbeing. The first part of the book focuses on research findings from He Oranga Ngākau: Māori Approaches to Trauma Informed Care, which supports health providers working with whanau experiencing trauma. It discusses tikanga Māori concepts, decolonising approaches and navigating mauri ora. The subsequent chapters explore indigenous models of healing, focusing on connections to land and the environment, whakapapa connections and indigenous approaches such as walking, hunting, and growing and accessing traditional foods for wellbeing. Important.

A Very Private Eye by Barbara Pym $30

Selected from the diaries, notebooks, and letters of this beloved novelist A Very Private Eye is a unique, continuous narrative autobiography, providing a privileged insight into a writer's mind. Philip Larkin wrote that Barbara Pym had "a unique eye and ear for the small poignancies of everyday life." Her autobiography demonstrates this, as it traces her life from exuberant times at Oxford in the Thirties, through the war when, scarred by an unhappy love affair, she joined the WRNS, to the published novelist of the Fifties. It deals with the long period when her novels were out of fashion and no one would publish them, her rediscovery in 1977, and the triumphant success of her last few years. It is now possible to describe a place, situation or person as "very Barbara Pym."

”One does not laugh out loud while reading Barbara Pym; that would be too much. One smiles. One smiles and puts down the book to enjoy the smile. Then one picks it up again and a few minutes later an unexpected observation on human foibles makes one smile again.” —Alexander McCall Smith

Bicycle by Jonathan Maskit $23

These days the bicycle often appears as an interloper in a world constructed for cars. An almost miraculous 19th-century contraption, the bicycle promises to transform our lives and the world we live in, yet its time seems always yet-to-come or long-gone-by. Jonathan Maskit takes us on an interdisciplinary ride to see what makes the bicycle a magical machine that could yet make the world a safer, greener, and more just place. There is so much that can be achieved if we apply our musculature to an external skeleton!

The Silver Bone by Andrey Kurkov (translated by Boris Dralyuk) $38

Kyiv, 1919. The Soviets control the city, but White armies menace them from the West. No man trusts his neighbour and any spark of resistance may ignite into open rebellion. When Samson Kolechko's father is murdered, his last act is to save his son from a falling Cossack sabre. Deprived of his right ear instead of his head, Samson is left an orphan, with only his father's collection of abacuses for company. Until, that is, his flat is requisitioned by two Red Army soldiers, whose secret plans Samson is somehow able to overhear with uncanny clarity. Eager to thwart them, he stumbles into a world of murder and intrigue that will either be the making of him — or finish what the Cossack started. Inflected with Kurkov's signature humour and magical realism, The Silver Bone takes inspiration from the real life archives of crime enforcement agencies in Kyiv, crafting a propulsive narrative that bursts to life with rich historical detail.

Long-listed for the 2024 International Booker Prize.

The Letter with the Golden Stamp by Onjali Q. Raúf $20

“I can't remember how old I was when I first started collecting stamps. But I've got a whole shoebox full of them now. Mam used to help me collect them ... Before she got so ill that she lost her job, her friends...everything. Now it's my job to take care of her and protect her - and my little brother and sister too. But to do that, I have to make Mam a Secret. A secret no-one can ever find out about. Not even my best friends at school, or Mo, our postman. Or the stranger living in the house across the street. The one no-one has seen, but who I know is spying on us. The one I think might be Them...”

Tibbles the Cat by Michal Šanda and David Dolenský $30

In 1894 Tibbles the cat moved to Stephens Island in the Marlborough Sounds to accompany her owner, the new lighthouse keeper. Tibbles ‘discovers’ a rare flightless species of wren, to the great excitement of ornithologists from around the world. Their demand for specimens and Tibbles’s natural habits soon caused the wren’s extinction, however. This event brought to the worlds attention the dangers of introducing exotic animals into fragile habitats.

Ngā Wāhine e Toru: Three Women by Glenn Colquhoun $45

In this collection of poems Glenn Colquhoun writes to his daughter, former partner, and mother, using the medium of Māori oral poetry. In doing so he explores oriori, karakia, haka, mōteatea, pātere, waiata aroha and waiata tangi. It is a companion volume to Myths and Legends of the Ancient Pākehā, his collection of oral poetry in English. Bilingual edition. “Māori oral poetry is a living tradition that is constantly added to. It contains remarkable stories. It uses metaphors drawn from our own land, sea and sky. It is sung to the tunes of the wind and of water and of birds. Working within its traditions I have come to see that at the heart of all poetry, written or spoken, is a kind of cry. And if a poem cries well, then its meaning is always simply in the nature of that cry first and foremost. Language, understanding, cognition, are always second to this. Of all of the arts practised by Māori and Pākehā our two poetries have remained the most stubbornly separated from each other over time. I hope these pieces go some way towards addressing that gap. More than anything else they are a gift to the people of Te Tii for all they have done for me. I have always hoped that I might finish them in time for some of those kuia who were there when I arrived on New Brighton Road bedraggled and naive, to listen to. They are the product of their work as much as my own.” —Glenn Colquhoun

Myths and Legends of the Ancient Pākehā by Glenn Colquhoun, illustrated by Nigel Brown $45

In this collection of poems Glenn Colquhoun explores a range of Pākehā oral poetic forms; sea shanties, hymns, ballads, nursery rhymes and clapping songs. It is a companion volume to Three Women, his collection of poetry in Te Reo Māori, and is richly illustrated by Nigel Brown. “It was by looking at Māori oral poetry more closely that I came to ask what it is that a Pākehā oral poem might sound like. And whether it is capable of holding the same power. Might a sea-shanty meet the energy of a haka? Can a hymn stand up to a mōteatea? To find out I went back to the ways that spoken English poetry first arrived in New Zealand: via sea-shanty and hymn, lullaby and nursery rhyme, working song, clapping song and skipping song. I also went back to what has often been the concern of oral poems, our histories.” —Glenn Colquhoun

A selection of books from our shelves. Click through to find out more:

READ AND RELAX! Enter our May competition and go in the draw to win a night for two at the truly paradisiacal Trehane Chill — the perfect place to relax and read (or write!). Tucked away on a 14-acre lifestyle block near Whakatū, surrounded by orchards, streams, and native bush, this escape offers a picturesque change from the ordinary. Every detail of Trehane Chill reflects thoughtful design and rustic elegance, and your stay will allow you to commune with nature while remaining in absolute comfort.

TO ENTER: Buy a book from VOLUME during May and tell us why you would like to read your book at Trehane Chill. Write your entry in the 'notes' field when checking out on our website, or just email it to us. The winner will be drawn on 3 June, and can use their prize before 1 October (we recommend adding this night to a longer stay!).

Chill book bundles: treat yourself to a bundle of books to read during your stay. We will choose them and have them waiting at Trehane Chill for you when you arrive.

Read our newsletter!

Choose from our annual cookbook sale.

Go in the draw for a night in paradise.

3 May 2024

Opening with the epigraph ”Live. Laugh, Love. — Ancient Human proverb,” you know that Turncoat isn’t going to be your standard Aotearoa fiction (that’s no surprise coming from the Lawrence and Gibson stable.) Your curiosity is piqued. “Ancient Human proverb” — sweet irony. I can already see large wooden letters sitting on shelves and hung on walls. If you’re lost, a meme dictionary or a quick google will come in handy but it won't matter, as there are enough wry references you will easily recognise that will keep you amused. Turncoat is hilarious. The satirical approach provides an accessible portal for Tīhema Baker’s critique of casual racism and institutional conflicts for Māori working in the Public Service. Step back, and walk into the future. It’s Revolution 9-4025 (2507 AD) and Kytoonoo 1 Daniel is determined to change the world. He’s young, idealistic, and believes that he can make a difference. Earth, now known as Teerin’ Ho (there are other excellent renamings; the Pacific Ocean’s new name is Extremely Large Water Expanse, and plenty of highly enjoyable word play) is dominated by the Aliens. They control the airspaces, have claimed important ancient Human places, have a grand city in the sky, Kappeetar, and have higher Rank (more power and money). There’s a Treaty, but, yes, there are two versions. The Common and the Noor. Does this sound familiar? So Daniel joins the Hierach with the ambition to change the system from within. And he starts to make some small wins, despite the fact that he is called everything from Dan-Yell to Denial. He’s rekindled his friendship with the sleekly coated Neekor, and feels that he is continuing to stay true to his familial relationships (his mother is the leader of New Zealand) and his childhood friendship with Hayden (Rank 0 and heading downward). Daniel works at the Chamber of Covenant Resolutions (ChamCov) where there’s a mix of Alien and Human employees, and works on Authorisation disputes. As long as he plays the game, it’s okay. A trip to Ireland, who want to settle their Authorisation independent of Britain, spells out the quandary of being a mouthpiece of the Hierach. As things escalate in both the political and personal spheres for Daniel, where will he stand? Suffice to say, over several Revolutions he goes from optimistic, through dumb-founded, to pessimistic, and a choice is imminent. There are no happy endings in this satire, but there is hope. Turncoat is an important, refreshing novel that does not shy from the truth of our race relations and obligations to Te Tiriti. Its humour and speculative setting give an opportunity to open your mind to the possibility of a different world order. If fiction does nothing else, it enables you to walk in someone else’s shoes. Walking is recommended.

While being generally uncomfortable about comfort, he wrote when asked what he read for comfort, in times of particular stress or despair I do find that re-reading any of the novels of Thomas Bernhard makes me feel better, though I am also uncomfortable about the concept of feeling better, he wrote. He had been re-reading Thomas Bernhard’s novel Woodcutters, a book that he had read before, and, indeed, reviewed before, so, he thought, he would not review it again, he would just read it for what he, not without irony, called comfort, not that he understood the word. Bernhard’s sentences are unrelentingly beautiful and his negativity so intense that it becomes ludicrous, he wrote. Everything exaggerated moves towards its opposite, so I often find my negativity turned, too, he also wrote, and then, he thought, I have finished answering the question I have been asked, not only answering it but explaining my answer, too, which was more than I had been asked to do, even though I have done it rather briefly. The first time he had read Woodcutters, he had been younger than the narrator, and younger than the author when he wrote the book, the narrator and the author sharing rather more than their age, he thought, but now he was older than the narrator, and older than the author was when he wrote the book, and also older than the author was when he died, or, rather, committed suicide, whichever is the better description of the author’s death. The narrator of Woodcutters has not committed suicide, obviously, and does not even do so at the end, but the entire novel is narrated in the evening of the day of the funeral of one of the narrator’s former friends, who, finding herself denied artistic success merely through mediocrity of talent, which is not necessarily sufficient to exclude someone from success, depending on how you understand the word success, but perhaps sufficient to exclude someone from success in what the narrator calls Vienna’s art mill, the art mill that grinds even those with talent into powder, most effectively by acclaiming their talent, and, by doing so, destroying it, whereas Joana, losing all that she had going for her, which is a strange turn of phrase, spent many years in alcoholism and despair, in decline, so to speak, and hanged herself in the village in which she was born, just before the narrator’s return to Vienna after an absence, apparently, of some twenty years. The host of the dinner party at which the narrator observes the proceedings without involving himself in them, as he says, was once a talented composer, or at least so it had seemed to the narrator when he had been involved with him twenty or even thirty years before, before the narrator had left Vienna in disgust with Vienna and with the artistic and literary circles of Vienna, but now the host has been destroyed by his talent, or by the acclaim accorded his talent, and in this way relieved of this talent, and the host, one Auersberger, or so he is called in the novel, though it is perhaps interesting to note that the book was banned in Austria after one of Bernhard’s former patrons reognised himself in the character, is now little more than ludicrous or pathetic. And the same could be said, and indeed is said by the narrator, albeit to himself, as he sits in a chair just off the main room, observing them, of the other guests at the dinner party, the dinner party styled by its hosts an artistic dinner held in honour of an actor who is rather late to arrive, but really more of a gathering of members of the artistic and literary circles that included both the narrator and Joana twenty or thirty years before, when the narrator, like the author, if the author can be distinguished even a little from the narrator, was an aspiring writer who was supported by persons like Auersberger, or by the person who recognised himself as Auersberger, writers who had talent but whose talent has been destroyed by Vienna’s art mill and other persons whose talent has been similarly destroyed. “As I see it they haven’t become anything. They’ve all quite simply failed to achieve the highest, and as I see it only the highest can ever bring satisfaction, I thought.” But, thinks the narrator, these people, the people of this so-called artistic circle, have been more than complicit in the destruction of their talent. “All these people have contrived to turn conditions and circumstances that were once happy into something utterly depressing, I thought, sitting in the wing chair, they’ve managed to make everything depressing, to transform all the happiness they once had into utter depression, just as I have.” When the celebrated actor finally arrives and the narrator moves with the other guests to the dining room, the narrator’s focus moves, if the narrator can be said to have a focus, from his opinions formed in the past of those present, attitudes which caused him to leave Vienna twenty years ago, when his love for those present, and for Joana, had turned entirely to disgust, when he had taken from them all he could, to his observations of what is said and done, though not said and done by him, who only observes the proceedings and does not participate in them, or so he says, in the present, at the artistic dinner itself, observations, it must be said, no less vitriolic but rather more ambivalent, by which I mean, the bookseller thought as he paused in his train of thought, a train of thought that had begun to resemble a review but was not a review but only a train of thought, unless a train of thought can be called a review, and he thought not, he thought, not the popular misconception of ambivalence as some wishy-washiness, if he was writing a review he would replace wishy-washiness with a better word, or at least an actual word, but ambivalence in its true, etymological and Freudian sense of being beset with equally overwhelming but opposite inclinations. The narrator, he thought, loathes those most like himself, all his loathing is self-loathing, and to loathe, therefore, is the greatest act of sympathy, the strongest form, he thought, of identification. “We are not one jot better than the people we constantly find objectionable and insufferable, those repellent people with whom we want to have as few dealings as possible although, if we are honest we do have dealings with them and are no different from them. We reproach them with all kinds of objectionable and insufferable behaviour and are no less insufferable and objectionable ourselves — perhaps we are even more insufferable and objectionable, it occurs to me,” the narrator of Woodcutters says. To grow older, the bookseller thought, is not to become more certain but to become less certain, certainty is for the young, he thought, certainty is for those who do not think, not that it is necessarily true that the young do not think, there are, no doubt, some who are young who do think, but they have not thought long enough, being young, to realise that all thought leads to the destruction of certainty, all thought leads to ambivalence, to the undermining of anything that might be said to be one’s own identity, there’s no such thing as one’s own identity anyway, he thought, except in the thoughts of others, and hardly even then, all thought is its own undoing. As the guests depart from the dinner, the narrator, the last to leave, thanks the hostess for a lovely time, after apparently hating it the whole time and hating everything about it and everyone who was there and everything they said and did, kisses her, and then runs through the streets of Vienna, away from his home, towards the centre of town, in the wrong direction, in a dishevelled state of mind, so to term it, completely dishevelled and confused. “To think that I was capable of such hypocrisy, I thought as I was speaking to her,” he says to himself about the only words he actually speaks in a book full of words. “To think that I am capable of telling her to her face the precise opposite of what I feel, because it makes things momentarily more endurable.” Well, thought the bookseller, I can understand that, we all tell others to their faces the opposite of what we feel because it makes things momentarily more endurable, and, in fact, we also do feel what we tell them, that is how we survive and that is how we destroy ourselves, we destroy ourselves by surviving and we survive by destroying ourselves, this is what thinking tells us if we think our thoughts through to the end, this is the truth that is hidden from the young by their youth, this is why I resist my own existence, at least internally, whatever that means, whatever form that resistance could take, and, at the same time, this is why I long to exist, for my nonexistence to end, though my nonexistence cannot end, it can only be obscured, for a chance to take refuge from thinking in busyness, so to call it, in the busyness of my life, the life I therefore both long for and resent. He felt comforted by this thought, he thought, my negativity has become so intense, he thought, through reading Thomas Bernhard or through the thinking that accompanies reading Thomas Bernhard, through thinking like Thomas Bernhard and not thinking like myself, that it has become ludicrous, and always was ludicrous. Everything exaggerated moves towards its opposite like this, he thought. I find my negativity has turned, he thought, and this, he thought, is a comfort.

Here they are! Some tempting bargains from our wonderful cookbook shelves. There’s plenty to savour here. Try a new cuisine, mix your own drinks, revitalise your sourdough, be creative with an innovative chef, grow your own spices, or take a philosophical walk with the humble potato!

If you think the tasting plate below looks delicious, enter here for more culinary treats!

James is an enthralling and ferociously funny novel that leaves an indelible mark, forcing us to see Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in a transformed and transformative light. The Mississippi River, 1861. When the enslaved Jim overhears that he is about to be sold to a new owner in New Orleans and separated from his wife and daughter forever, he decides to hide on nearby Jackson’s Island until he can formulate a plan. Meanwhile, Huck Finn has faked his own death to escape his violent father who recently returned to town. Thus begins a dangerous and transcendent journey by raft along the Mississippi River, toward the elusive promise of free states and beyond. James is Jim’s story as Huckleberry Finn is Huck’s. Everett is at his most playful with the things he is most serious about: language, racism, justice, liberty; this book is clever, farcical, exuberant, unsparing — and a huge amount of fun to read.

A selection of books from our shelves ready to move to your shelf. After all, what could be better? Immerse yourself in a book today.

Click through to find out more:

After Hours Trading & The Flying Squad

Dangerous Experiments for After Dinner

New books for a new month! Click through to our website for your copies:

Brown Bird by Jane Arthur $20

Sometimes it can take one special friend to show you what you’re capable of, even if does take you a while to believe it. Eleven-year-old Rebecca tries to make herself invisible so people won’t call her weird. Resigned to spending the holidays by herself in a new neighbourhood while her mum works long hours at the supermarket, she meets Chester, who has come to stay for the summer. He is loud and fun and full of ideas. But will Rebecca be able to cope with being taken so far from her quiet comfort zone? Rebecca is about to find out that she can be braver than she ever thought possible . . . The book is beautifully written; Jane Arthur perfectly captures the voice of eleven-year-old Rebecca, and expresses the uncertainties, awkwardnesses and hopes that we all experience.

James by Percival Everett $38