BOOKS @ VOLUME #195 (11.9.20)

BOOKS @ VOLUME #195 (11.9.20)

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

The Phantom Twin by Lisa Brown Ever wanted to run away to the circus? Maybe, think again. Lisa Brown’s graphic novel The Phantom Twin lays bare the hardship endured, as well as belonging provided, by the circus — in this case, the sideshow carnival of the 1920s for the unwanted and the freakish. Isabel and Jane are conjoined twins sold to the dastardly Mr Carlisle — the owner of the sideshow. Sharing an arm and leg isn’t much fun, especially when Isabel's sister, Jane, is the boss. When Isabel would rather stay in, drawing, Jane wants to go out and enjoy herself. Dancing and acting on stage, with Mr Carlisle ‘taking care’ of their money, isn’t what either girl wants, but in a world with no parents, their only family being their fellow obscurities, and no home, a way out doesn’t look too promising — until Jane meets an ambitious surgeon. Jane sees a chance for them both to have a ‘normal’ life, but the surgery to part the girls goes wrong and Isabel is left with a clumsy prosthetic arm and leg and no sister. Well, a sort of sister, a phantom twin. With nowhere to go, Isabel returns to the carnival and into the care of Nora, the tattooed lady, who encourages her to make a new life for herself. But without Jane, what can she be? Carlisle grudgingly lets her stay and gives her a new role — the mechanical doll. Haunted by her sister, who badgers her to leave the carnival, Isabel is constantly aware of this phantom at her side. Will Jane ever let her go and does she really want her to go? Fortunately, she has a friend in Nora, and she shows her the possibility of a way out of her dilemmas, initially introducing her to someone that can make her better prosthetics and who, later, will open a window to her talents. With the carnival falling on hard times, there’s a journalist sniffing around for a scandal, and Isabel finds herself at the centre of drama she is unfairly blamed for and life seems to go from bad to worse. Who will save her now? Lisa Brown’s comic-style drawings are flat and colourful, with a blue palette that underscores the depression times and the hardships that befall Isabel. There are also pockets of radiant reds and greens, reflecting the excitement and entertainment aspects of the sideshow and the fabulousness of its players. Lisa Brown uses colour to highlight emotional drama too, with intense dark scenes and endearing moments in bright and lively tones. The illustrations also subtly portray the fringes of society in depression-era America giving the reader an insight into this difficult but fascinating period. At the conclusion of the book, in the author's notes, Brown shares some of her research into the carnival and the real people who found themselves on the stage. Aimed at teens, The Phantom Twin would be suitable for most ages with its quirky and thoughtful exploration of difference, friendship, coming-of-age and falling in love, identity and realising your true talents. A ghost story with a happy ending. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

| Grove: A field novel by Esther Kinsky {Reviewed by THOMAS} “Absence is inconceivable, as long as there is presence. For the bereaved, the world is defined by absence,” she wrote. She went to Olevano, some distance from Rome, in the hills, in the winter, two months after her partner died, the bereavement was taking hold, she no longer fitted into her life. It was winter, as I said, she stayed alone in Olevano, she looked out of the window, she went for walks, she took photographs, she wrote. The whole place, and the text she wrote, was cold, damp, dim, filled with mist, vagueness, echoes, mishearings. Well, of course. This is not to say that her observations were not precise, preternaturally precise, and the sentences she wrote to describe them, they too were preternaturally precise, whatever that means. “In the unfamiliar landscape I learned to read the spatial shifts that come along with changes to the incidence of light.” She is unable to think of the one who is lost, rather, the one she has lost, she is unable to face an absence that at this time is an overwhelming absence, instead she observes in minute detail, with great subtlety, as if subtlety could be anything but great, the particulars of the day and the season, the fall of light, those things that only she could notice, or only a bereaved person could notice, the weight of noticing shifted by her bereavement, death pulling at everything and changing its shape, changing the fall of light, even, or making her aware of changes in the fall of light, and in the shape of everything, so to call it, that are inaccessible to the non-bereaved. There are other worlds, but they are all in this one, wrote Paul Éluard, apropos of something, if it was him who wrote it, and if that was what he wrote, if these are different things, but as we can cope with the world only by suppressing almost everything that comes at us, even at best, we notice only as our circumstances allow, our mental circumstances, our emotional circumstances perhaps most significantly, and we are somehow sharing space but seeing everything differently from others and some more differently than others. We live in different worlds in the same world. She was bereaved, she saw what she saw, observed what she observed, with great precision and intensity as I have said, out of the mist, among the fallen leaves. There is a cemetery in every town, or vice-versa, she visits them all, acquaints herself with the faces of the dead, but not her dead, not the one of whom she is bereaved. She writes of herself in a continuous past, “I would.” she writes, “Each morning I went,” she writes, as if also all that is observed also continues in this continuous and unbordered way, which might be so. Death, first of all, is an aberration of time, bereavement acts on time like a point of infinite gravity that cannot be observed but which bends all else. Memories are the property of death, there can be no memories if she is to face each day, though the memories pluck at her in her dreams. She observes, she wanders, she acts on nothing, she changes nothing, the season moves slowly through darkness and chill. She travels to the nearby towns and into the hills, the mists. She recognises herself more in those displaced like her to Italy, the migrants and the refugees, those for whom no easy place welcomes them, those who have lost something, recently, that the others around there have perhaps not recently lost. “We sized each other up as actors on a stage of foreignness,” she writes, “Each concerned with his own fragmented role, whose significance for the entire play, directed from an unknown place, might never come to light.” She is aware, everywhere, of the loss that outlines and gives shape to that which goes on, and the mechanisms of loss that are built into the function of a whole town, or a whole human life. She sees the junkyard by the bus station, “an intermediate space for the partially discarded, whose time for final absence has nevertheless not yet arrived.” She visits the Etruscan tombs and sees the reliefs there as a membrane separating the living from the dead, their loss is one of space as well as of time, what is shared between her and them is two dimensional only, “as if the dead would know how to reach through the cool thickness of the masonry to touch the object’s or animal’s other side, invisible to us, and hold it in their life-averted hands.” The membrane is infinitely thin. It is only two dimensions. It is everywhere. She asks, “Will it wither away, the hand I pull back from the morti?” Time passes. Something unobserved is changing beneath the changes she observes, “the Spring air a different shade of blue-gray.” She leaves Olevano and leaves the first section of the book. Because she, we, you, I perceive only a fraction of what we could call the external, the fraction to which we are at a moment attuned, it is easy to fall out of tune with others. For her, whom bereavement has differently attuned, or untuned, her reattunement must be achieved by words, she who lives by words must recalibrate her world through words, descriptions, care, precision, nuance, it is wrong to think of nuance as somehow imprecise, it, all this, is an exercise in slowness, and we who read must also change our speed to the speed of her noticing if we are to experience the text, if we are to experience, through the wonder of her text, somehow, her experience, or something thereof. The external reveals itself only to those moving at the precise right speed of perception, so she shows us, and so too her text reveals itself only to those moving at the precise right speed, those who read the text at the speed the text requires. In the second section she remembers, memory being the province of death, or vice-versa, her father, of whom she has also been bereaved, a little longer ago, and the holidays in Italy of her childhood, with him, and, presumably, with her mother, though this section deals specifically with memories of her father, perhaps because her mother is still alive, if she is still alive. This section is the section of the father, of the memories of the father more particularly, the only way her father now exists, he has finished contributing to memories that might be had of him and fairly soon these memories become the memories of memories, the parts magnified becoming still more magnified, the other parts abraded, becoming lost. Each memory contains a necropolis, it seems. With nothing, she begins the third and final section. She rents a cottage, so to call it, in the delta of the Po. Marshes, salt pans, mists again, fogs, rains. Birds. It is winter. “Everything had been repeatedly disturbed, was forever suspended between traces and effacement.” All that is human, and all of nature is abraded. “It was even hot when I arrived, the air similarly gray and viscous, and the landscape lay motionless, disintegrating under its weight; on hillcrests and in the occasionally visible strips of riverbank clung fragments of memory that had been torn away from a larger picture and settled there.” Time moves differently, again, here, she lets it, broken things stand about, the past is forgotten but is everywhere, is in the dust and mud, more often mud, the rain, the fog. “It was a place that could only be found in its absence, by recalling what was lost, therein lay its reality.” But here in this slow nowhere something almost unperceived begins to change, the emptiness provides a space, the past gets somehow out of her, death begins not to completely overwhelm her, memory relinquishes something of its choke. She even gets a ride to town with the owner of the cottage, in his car. Perhaps she comes to think that history is the proper province of the past. “Among the places of the living are the places of the dead,” she says, and not vice-versa nor one inside the other. She visits Ravenna and in Ravenna the two mosaics spoken of to her by her father not long before his death, actually the last time she saw him before his death. The mosaics are now outside her, sensed, and no longer trapped inside, her father’s experience of the two blue mosaics likewise no longer trapped, the experience of her father, something of a connoisseur of blue, no longer confined inside the one who is bereaved, the bearer of his memory, but somehow shared with her. These two mosaics, I wonder, for her, also a connoisseur of blue, are, perhaps, the mosaic of life and the mosaic of death. “These two mosaics — the dark-blue, bordered harbour with its still unsteady boats; and the light-blue expanse with no obstruction, nothing nameable, not even a horizon.” |

NEW RELEASES

Mordew by Alex Pheby $38Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward $28

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

Summer by Ali Smith {Reviewed by STELLA} In the final book of the 'Seasons' quartet, Ali Smith once again delivers a brilliant and splendid novel, Summer. Opening with some true and awful happenings in recent times — government corruption, politicians who openly lie, raging fires due to climate change, the rise of fascism, rejection of refugees — and the upshot of these challenges being a shrug accompanied by a 'So?', Ali Smith cuts to the core of an apparently apathetic modern culture. But then, it’s also not. Protest, both peaceful and disruptive, activism via social media and the rise of mass action (Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion) all have their moment in this novel, which is set precisely now. Yes, even Covid is there. For a publishing industry that moves traditionally slowly, Ali Smith has pulled off some kind of feat: a book written and published absolutely in the moment. As with all the quartet, Smith draws on her vast knowledge of art and literature, and for Summer we have references to Dickens and to Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, as to well less-known figures such as filmmaker Lorenza Mazzetti. And while the books are experimental in nature — the novel doing something to us with its mirror to our immediate world — Smith also gives us excellent story-telling, cleverly tying us back to her first in the series, Autumn. Enter sixteen-year-old Sacha and her precious (yet brilliant) brother Robert and their family. Their parents are living in separate houses next door to each other, driven apart, in part, by their differing views (and votes) on Brexit. Sacha is fighting against political apathy and Robert is quoting new right rhetoric. When Robert hinders Sacha with time (you’ll have to read Summer to find out what happens) the family strike up an unexpected meeting with Arthur and Charlotte, on-line media writers, who are on their way to return an object (which just happens to be a Barbara Hepworth sculpture) to Daniel Gluck. You might remember Gluck from Autumn — the 100yr-old man whose dreams we entered. And here, we step back in time with Daniel to 1940 and the internment of alien persons in England during WWII. Daniel and his father are interned as German Englishmen (Daniel is Jewish), while his sister is somewhere in France working for the resistance. Here you have a focus on another time which was fraught with difficulties, with delusions and despair, but also it was a strangely creative and communal time — many European artists, musicians and writers who had escaped fascism, were rounded up and imprisoned together and this was a springboard for postwar endeavours. Summer is a book that will both stun you and fill you with hope, moments of kindness, forgiveness, and a window to a better world if we dare to step through. There is so much in these pages that you will be immersed without trying, and like all the books in this quartet, it operates on several layers (the stories, the art, the literary references, the political landscape, the ability of art to act as a catharsis, and the exploration of what a novel can be) allowing you, as the reader, to dive as deeply as you wish. Full submersion recommended. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

| Translation as Transhumance by Mireille Gansel (translated by Ros Schwartz) {Reviewed by THOMAS} “What does a language retain of the violence it has been used to commit?” asks Mireille Gansel in this short, thoughtful book about what we could call the deeper strata of languages, their consonance and resilience. After witnessing first-hand the fracture of the transnational Mitteleuropean German by Nazism and the concomitant reduction of its polymorphism to relatively depthless bureaucratic functionality, she asks, “How do you bridge the abyss created in the German language by the barbed-wire fences and watchtowers of history?” But of course, though not without hardship, language is itself the means to overcome the depredations inflicted upon it. As Paul Celan wrote, “Reachable, near and not lost, there remained amid the losses this one thing: language. It, the language, remained, not lost, yes in spite of everything. But it had to pass through its own answerlessness, pass through frightful muting, pass through the thousand darknesses of death bringing speech.” For Gansel, who has had a long career translating poetry into French from German, and also, in the early 1970s, from Vietnamese (as an act of solidarity with the Vietnamese people), it is in language that the struggle for identity, freedom and self-determination must be enacted, and where can be found “the ultimate refuge: poetry as the language of survival.” It is in poetry, not only in the meanings of the words but in the layers of meaning that are inherently structural, in the relationships between form and cadence, between metre and rhythm that form the inner architecture of a language and which can only be reached through poetry (or, rather, of which poetry is the symptom of an encounter), that the particular can act as a universal and translate itself, whole and unchanged, into a particular within the patterns of structure and meaning that form another language. “No word that speaks of what is human is untranslatable,” writes Gansel. The ‘transhumance’ of the book’s title suggests that texts can be enabled to migrate to new contexts just as flocks may be moved to new pastures in order to survive, to grow and to multiply. As contexts change, in time or place or with the rigours of historical circumstance, the requirements of translation change, though the original text remains the same, intact. Translating poetry, for Gansel, is a deeply political act, an inwardly political rather than an outwardly political act: “I learned the accents of an interior language. A language of poetry experienced and shared at the source itself, the very place where it is under threat.” The particularities of a language are unique to each region, each context, each person, and to understand and translate a poem or other text requires great humility, acuity and discipline. “The stranger was not the other, it was me. I was the one who had everything to learn, everything to understand, from the other.” There can be no true translation of poetry without consideration of the breath-patterns, the “ballet of cesurae” that structure the original poem. As she worked more and more deeply, for Gansel “translation came to mean learning to listen to the silence between the lines, to the underground springs,” and the core of a poem is “like drawing a breath, a breath of utterance that was both specific and universal.” A successful translation cannot be achieved without clearing language of its habitual grime and rediscovering “the sensuality beneath the shell of common abstractions.” Each poetry is “a different way of being open to the world,” preserving and conveying quite different and often more subtle freightings of personal and collective identity and experience than, say, folklore or material culture, and at once both more fragile and more robust than folklore or material culture. One of Gansel’s great achievements has been to translate the entire works of the poet Nelly Sachs from German into French. Sachs laboured to heal the damage done by Nazism to Mitteleuropean German, to reinstate particularly a Jewish tincture to the language from which it had been expurgated by the Holocaust, “to join the mutilated syllables,” to make poetry possible in such a way that trauma can be both given voice and overcome, to find once again “that German language, the crucible language of Mitteleuropa, the language on which the Nazi ideology had no grip, because it is a language of the mind, without a territory and without borders and with multiple affiliations, a language that is both supranational and at the same time the sanctuary of each dialect.” Gansel and Schwartz, consummate translators, are invisible stomata through which meaning passes between languages, even when the meaning is, paradoxically, inextricable from those languages. |

Book of the Week: Summer by Ali Smith. Smith's outstanding quartet, written 'in real time', comes to its conclusion with this eagerly anticipated and completely wonderful novel. Facing down some of the biggest issues of our time, Smith remains always playful, personable and pleasurable to read.

"These novels, in straddling immediacy and permanence, the personal as well as the scope of a world tilting toward disaster, are the ones we might well be looking back on years from now as the defining literature of an indefinable era. And the shape the telling takes is, if not salvation, brilliance itself." —The New York Times>>Read Stella's review.

>>Read Stella's reviews of the other books in the quartet: >> Autumn. >>Winter. >>Spring.

NEW RELEASES

FLAVOUR by Yotam Ottolenghi and Ixta Belfrage $60

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

| The Animals in That Country by Laura Jean McKay {Reviewed by STELLA} It’s the flu, but nothing like you have seen before. When Laura Jean McKay started writing her latest novel, The Animals in That Country, she had no idea she would be launching her book virtually because she would be in lock-down in New Zealand during a worldwide pandemic! So, you might not be in the mood for a ‘plague’ book, but this one will surprise you. It’s completely unexpected and refreshing. The Zooflu has hit Australia and everyone is getting pinkeye and talking to the animals. Enter our heroine — if you could possibly call her that — Jean, and her animal companion, a dingo called Sue. Jean’s an alcoholic, chain-smoking (if she can get any ciggies) brassy mess with a heart, her greatest love being her grandchild Kimberly, working as a tour guide at a wildlife park and hankering after a ranger’s job — one that Ange, the boss and also Kimberly’s Mum, won’t give her. Sue, an inmate at the park, is the top dog in the enclosure and hankering for a bit of freedom. When the Zooflu hits the park despite their best efforts to keep it out, everything goes to custard. Food is short, the animals are restless and the workers are cracking up, running away or talking to the animals. Or often, trying to communicate that they, the warders are not the enemy. The Zooflu hits everyone with different intensity — the most severe being communication with insects, which leads to some very trance-like experiences for the human species. As Jean finds out, being able to communicate with the animals — she has always wondered what they have been thinking and in the past and has articulated their wants aloud to anyone that would listen — isn’t a walk in the park, and their ways of talking are vastly different from human patterns, with layered meanings and oblique messages for their human companions. When Jean’s wayward son, Lee, turns up at the fence begging to be let in, despite being infected, Jean succumbs, much to her regret. A few days later he’s gone, taking Kimberly with him. Off to see the whales. (The idea of communing with the whales will never have the same resonance after you read this novel). Jean’s guilt drives her to follow, despite the crisis of the wildlife park in freefall (Ange is talking to reptiles, including the crocodile), with Sue by her side. As they traverse Australia — a remade wilderness of human proportions, as resources (fuel, food, alcohol) become scarce and hardy fellows in utes and with guns roam in packs, blocking their ears and noses with anything that comes to hand to keep out the sound and scents of animals — Jean becomes increasing feral and reliant on Sue to help find her granddaughter. Their travels are both hilarious and tense with both animals and humans. Popping in to see her Mum at the old folks' home, she finds the elderly happily interacting with the birds. They free a load of confused pigs from a truck, watch a child lost to the ants, hear the birds call out ‘not yet, not today’ for Jean’s eyes and other tasty morsels, come across towns where animals aren’t welcome, get robbed of petrol and take to the road on foot, meet oddities isolated in their own madness, and others celebrating their new communion. The Animals in That Country is a crazy, yet deeply philosophical, novel about our relationship with animals, what we see and fail to see, and our role as only one of the species in our ecosystem. And with Jean and Sue and their changing power relationship at the centre of this story, you are rewarded with a sharply funny, bizarre and profound exploration of these themes. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | ||

| Essayism by Brian Dillon {Reviewed by THOMAS}

|

Set in a plague-stricken Elizabethan England, O'Farrell's tender and incisive novel HAMNET looks at the effects on William Shakespeare and his wife Agnes of the death of their son Hamnet.

>>Read Stella's review.

>>Read an excerpt.

>>Unlike anything else.

>>"I wanted to give this boy, overlooked by history, a voice."

>>The cat has just woken up.

>>Maggie O'Farrell talks with Paula Morris at the AWF.

>>Unlimited.

>>What is known about Shakespeare's wife?

>>Life before Shakespeare.

>>Shakespeare's Wife by Germaine Greer.

>>The twins are baptised.

>>Hamnet in the burial register.

>>"This story is too sad."

>>Shortlisted for the 2020 Women's Prize for Fiction.

>>Not quite live at Elsinor.

>>Nobody home.

>>Your copy.

>>Some other books by Maggie O'Farrell.

NEW RELEASES

Summer by Ali Smith $34

Smith's outstanding quartet, written 'in real time' comes to its conclusion with this eagerly anticipated volume.

"These novels, in straddling immediacy and permanence, the personal as well as the scope of a world tilting toward disaster, are the ones we might well be looking back on years from now as the defining literature of an indefinable era. And the shape the telling takes is, if not salvation, brilliance itself." —The New York Times

Read Stella's reviews of the other books in the quartet: >> Autumn. >>Winter. >>Spring.

Wild Swims by Dorthe Nors $23

The Danish writer Dorthe Nors creates a series of intimate, psychologically acute portraits of individuals in states of emotional crisis: a woman's attempts to cope with a recent breakup lead her to commit a deeply immoral act, a professor's relationship with a much older woman takes a sudden sinister turn, a man who has grown resentful of his partner takes drastic action, and a young woman's nostalgic memories of wild swimming draw her back to the water. In attempting to escape the present moment, Nors's characters must confront the impact of the past. In prose that is both elegantly spare and saturated with emotion, Nors explores the relationships that we have with others, and those we forge with ourselves.

>>Beyond hygge.

There is the Cornwall Lamorna Ash knew as a child — the idyllic, folklore-rich place where she spent her summer holidays. Then there is the Cornwall she discovers when, feeling increasingly dislocated in London, she moves to Newlyn, a fishing town near Land's End. This Cornwall is messier and harder; it doesn't seem like a place that would welcome strangers. Before long, however, Lamorna finds herself on a week-long trawler trip with a crew of local fishermen, afforded a rare glimpse into their world, their warmth and their humour. Out on the water, miles from the coast, she learns how fishing requires you to confront who you are and what it is that tethers you to the land. But she also realises that this proud and compassionate community, sustained and defined by the sea for centuries, is under threat.

This book records an ongoing experiment in living differently, living better, and living more justly in an urban world. We live in the city of men. Our public spaces are not designed for female bodies. There is little consideration for women as mothers, workers or carers. The urban streets often are a place of threats rather than community. What would a metropolis for working women look like?

Those Seal Rock Kids by Jon Tucker $23

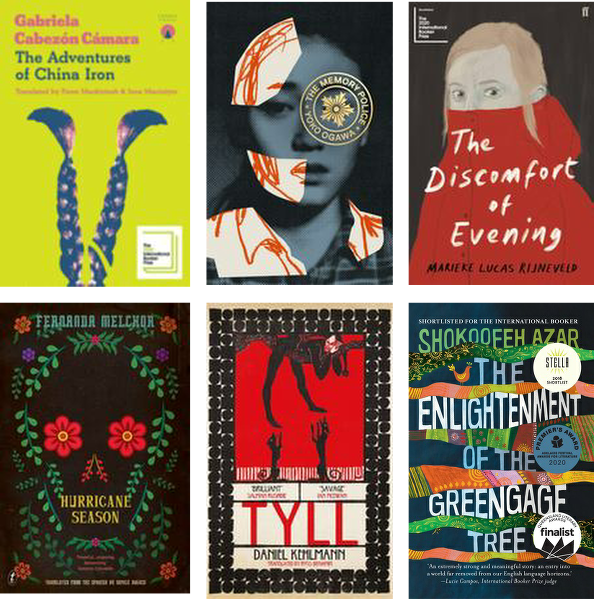

There are some remarkably good books short-listed this year for the International Booker Prize. The winner will be announced in a few days (on 26 March). Tell us which book you think should receive the award.

There are some remarkably good books short-listed this year for the International Booker Prize. The winner will be announced in a few days (on 26 March). Tell us which book you think should receive the award. - The Adventures of China Iron by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara (translated by Fiona J. Mackintosh and Iona Macintyre from Spanish). >>Find out more. >>Start reading.

- The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa (translated by Stephen Snyder from Japanese). >>Find out more. >>Start reading.

- The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (translated by Michele Hutchison from Dutch). >>Find out more. >>Start reading.

- Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor (translated by Sophie Hughes from Spanish). >>Find out more. >>Start reading.

- Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann (translated by Ross Benjamin from German) >>Find out more. >>Start reading.

- The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar (anonymously translated from Farsi). >>Find out more. >>Start reading.

| >> Read all Stella's reviews. | |

| A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne {Reviewed by STELLA} John Boyne has written the quintessential everyman’s novel. It has an intriguing premise: spanning all history with one man’s story at its centre ranging in time from AD 1 to 2016 and following a life from birth to an unknown future self (the epilogue / future self is intriguing). We meet our traveller through time in the opening pages, at his birth. It’s Palestine AD 1 and he is the second son to be born to a proud, violent father and a caring, slightly unorthodox mother. As you can imagine, the second son cannot please his father no matter his significant creative and imaginative talents that range (over time) from young artist to gifted craftsman (in various fields) to a spinner of words in many forms. A father that would rather rage against the world as soldier and womaniser with unfettered pleasure sees little use in the talents of his son and bemoans the fact that his first son has fled the home for greater adventures leaving him the hopeless second. This is a novel with family at its centre — firstly the child and his family, then later the man and his wives and children. Much misery, as well as joy, befalls our hero, and revenge or justice plays a large role in this man’s journey. There are some wonderful explorations and descriptions of place and the time. And highly enjoyable are the cameos of the famous and infamous dotted throughout the book. Our man in his various guises works on the Buddhas in Afghanistan, he is an assistant to Michelangelo, he sails with Abel Tasman and shares a jail with Ned Kelly. Each chapter propels us through time in about 50-year leaps: in the first part, entitled 'A Traveller in the Dark', we start in Palestine, find ourselves in Turkey, AD 41, then on to Romania AD 105 and Iran AD 152 and through to Italy AD 169. It’s a fascinating way to pin some of the greater historical moments into a work of fiction, and it is a work of fiction (licence can be allowed with the ‘facts’ as long as it stays convincing). For this is a novel where you are propelled forward by your involvement in this man’s plight, in his loves and hates, in his wanderings to find a sense of peace in either new places or new relationships, his joy of having a child, his pleasure in success, and his anger and sorrow when the fates strike him down. There are some wonderful moments in the book that keep you hooked firmly in this story. Italy, AD 169 — being forced as a child to be the Emperor’s son’s playmate to the extent of being locked in with him when he has the plague to keep him company. AD 260, Somalia — after finding himself captured during battle and becoming a slave. In Switzerland AD 214 — he finds himself in the opposite position: a slave owner. This juxtaposition balances the conflicting aspects of our traveller. In the fifth part, Boyne manages to place the action in a series of monasteries and chapels. Devastated by a mishap in his life, the man finds refuge in these peaceful places and uses his skills to pay his way. In Ireland, 800 AD, he is an illuminator; in Indonesia, AD 907, a sculptor. And so this pattern continues as he seeks the answers to his life’s misfortunes and seeks his cousin who has wronged him. The confrontation when it comes is not what he expects. Across time and place, he finds his brother, takes opportunities, seeks a family of his own, and encounters actions that harm him and others. A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom is ambitious, and like all of John Boyne’s novels, it is great story-telling: clever and inventive. |

| >> Read all Thomas's reviews. | |

| Speedboat by Renata Adler {Reviewed by THOMAS} You’re soaking in it, he said when I asked him how he was getting on with the review of Renata Adler’s novel Speedboat, the review he was supposedly writing for the newsletter that his bookshop issued each week. You’re soaking in it, he said, but he did not elaborate further, and it was unclear to me what he meant. He was referring, perhaps, to the decades-old advertisement for a dishwashing liquid that softens your hands while you do the dishes, if we are to believe the advertisement, a liquid that undoes the effects of work upon the worker, a liquid that leaves a person who commits a certain act seeming less like a person who would commit that act than they did before they committed that act, in this case washing the dishes but presumably the principle could apply to anything, providing that the appropriate liquid could be found. You’re soaking in it, he repeated, and, yes, I thought that perhaps he was right, we are immersed always in something that undoes the effects upon ourselves of our own intentions, something that Adler alludes to when she writes, “For a while I thought that I had no real interests, only ambitions and ties to certain people, of a certain intensity. Now the ambitions have drifted after the interests, I have lost my sense of the whole. I wait for events to take a form.” But there is an uneasy relationship between the narrating mind and the world in which it soaks, in which it is softened as it does its work, he might think. “Situations simply do not yield to the most likely structures of the mind,” wrote Adler. The world in which we soak is comprised of random events, or at least of events sufficiently complex as to appear random or to be treated without fear of correction as random, he might think, a world of discontinuity, of agglomeration and dissolution, of fragmentations, collisions and tessellations, he might think, a world in which the one who is soaking in it instinctively, or, perhaps, instinctually, it’s hard to tell which, searches for meaning even while acknowledging its impossibility, for this, he probably is thinking, is the nature of thought, or the nature of language, if that is not the same thing. We cannot help but narrate, narrate and describe, observe and relate. There is no meaning, I suppose he is thinking as he contemplates, or as I suppose he contemplates, the review he could be writing of the book that he has read, or claims to have read, may well have read, no meaning other than the pattern we impose by telling. Stories both create and consume their subjects, he thinks, I think, or he might as well think. Writing and reading, the so-called literary acts, are concerned with form and not with content, or, he might say, more precisely, concerned primarily with form and only incidentally with content, so to call them, he might think, the literary acts are patterning acts and it is only the patterning that has meaning. Renata Adler writes beautiful sentences, he thinks, and this you can tell by the small pleasant noises he makes while reading them, she turns her sentences upon the sharpest commas. The comma, is the way in which life, so to call it, impresses itself upon us. Each assertion Adler makes is mediated by the realisation that it could be otherwise, either in point of fact, or in change of context, perspective, or scope. There is no progress without hesitation: no progress. Each comma is a rotation. There is humour in precision. “Doctor Schmidt-Nessel, sitting, immense, in his black bikini, on a cinder-block in the steam-filled cubicle, did not deign immediately to answer.” Speedboat is filled with such perfect sentences arrayed on commas. Sentences in paragraphs, often brief, filled with the jumble, so to call it, of the life of its ostensible narrator, Jen Fain, but, perhaps, of the life of Renata Adler, if such a distinction can sensibly be made, the narrator does not observe herself but those around her, she is a space in what she observes, she is an outline in the snippets that attach themselves to her. The real subject of the book, though, is language, others’ and her own. The book might be a novel, it is almost a novel, it is a novel if you don’t expect a novel to do what a novel is generally expected to do, it is information is caught in a sieve, the nearest to a novel that life can resemble, if this is of any importance. All novels, even the most fantastic, are comprised predominantly of facts, he is probably thinking, if he is in fact thinking, and it is only the arrangement of facts that comprises fiction. Adler’s narrator is entirely extrospective. She reports. She dissolves the distinctions between novelist, gossip columnist, journalist, and spy, the distinctions that were always only conceptual distinctions in any case and not distinctions of practice. Fain wonders what several of her friends actually do who have become spies. “I guess what these spies — if they are spies, and I’m sure they are — are paid to do is to observe trends.” Fain as a journalist cannot conduct an interview, she cannot impose herself to seek an answer, she has no programme, she can only observe. At one point she “receives communications almost every day from an institution called the Centre for Short-Lived Phenomena”. Her news, and it is news, is her own life, but not herself within it. She knows the risks: “The point changes and goes out. You cannot be forever watching for the point, or you will miss the simplest thing: being a major character in your own life.” Is meaning a hostage to circumstance, or is it the other way round? When the narrator starts to think about the world in terms of hostages it is because she has what she sees as a hostage inside her, a pregnancy she has not told her partner about, all things are hostages to other things, this is perhaps a sort of meaning. Hostages are produced by grammar. There he sits, hostage, I suppose, to his intention to write a review, or at least to the set of circumstances, odd though they may be, that contrived to expect of him this review, the review he will not write, disinclined as he is to write, though he will say, I am sure, if you ask him, that he enjoyed the book Speedboat very much. He makes no presumption upon you. As Jen Fain or Adler writes, “You are very busy. I am very busy. We at this rest home, this switchboard, this courthouse, this race track, this theatre, this lighthouse, this studio, are all extremely busy. So there is pressure now, on every sentence, not just to say what it has to say but to justify its claim on our time.” |

NEW RELEASES

Mihi by Gavin Bishop $18

This beautiful te Reo board book introduces ideas of me and my place in the world in the shape of a simple mihi: introducing yourself and making connections to other people and places. Essential.

Marti Friedlander: Portraits of the Artists by Leonard Bell $75

Friedlander's incisive photographs chronicled the country's social and cultural life from the 1960s into the twenty-first century. From painters to potters, film makers to novelists, actors to musicians, Marti Friedlander was always deeply engaged with New Zealand's creative talent. This thoughtfully assembled book shows us new sides of both well-known and forgotten artists and writers.

Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen by Camille Laurens $38

She is famous throughout the world, but how many know her name? You can admire her figure in Washington, Paris, London, New York, Dresden or Copenhagen but where is her grave? She danced as a 'petit rat' at the Paris Opera. She was also a model, she posed for painters and sculptors - among them Edgar Degas. Taking us through the underbelly of the Belle Epoque, Laurens casts a light on those who have traditionally been overlooked in the study of art, and opens a space for essential questions. She paints a compelling portrait of Marie van Goethem and the world she inhabited, in the 1880s; a time when art unsettled the hypocrisy of society.

"It’s a wonderful book, a little jewel, the way the author tries––discreetly, with respect and even a bit of shyness––to approach the dancer and through her the vices of representation, the injustice of the transformation of an individual into a figure, is quite beautiful, and touches on what for me is one of the most significant problems for fiction: how we try to understand someone else while honoring that inner secrecy they will always possess and we never will be able to grasp––the paradox, you know, of how we never understand and yet are condemned to understanding, however far our way of understanding is from approximating the real inner nature of the people we contemplate.’ — Adrian Nathan West

Who Sleeps with Katz by Todd McEwen $36

The doctor delivers bad news. What's a man to do, with the life he has left to live? He can cry, he can wonder which particular cigarette did it - the 564,119th or the 976,835th - or which brand. Or (and as well) he can call the friend he loves in the city he loves and then set out down the avenues and streets of New York to meet him. Every corner, every block has a memory: women, food, drink, friendship, the comedy of office life and of sexual success and failure. It's as though the towers of Manhattan have become a shelf of books, each to be opened and regretfully read for the last time. A journey, truly, of a lifetime.

"Ferocious wit, a stream of magnificent sentences, something to savour on every page, and a blissful knowledge of what really matters in life." – Guardian

"One of the great American novels. Overwhelming – as great and sad a love song as New York has ever inspired." – Salon

A Respectable Occupation by Julia Kerninon $28

"The best early training for a writer is an unhappy childhood," Hemingway famously said. Julia Kerninon, one of France's most acclaimed young novelists, tells an altogether different story in a poetic account of her pursuit. Her ode to reading, and to writing as a space for discovery (as well as a 'respectable occupation') entwines the French and Anglo-Saxon literary traditions as she journeys through her formative years.

"The greatest writers are also the greatest readers. Virginia Woolf, Roland Barthes, Jeanette Winterson - they all read, as Woolf put it, 'to refresh and exercise their own creative powers.' They can't stop themselves from writing about reading. They have origin stories of how reading and writing became as necessary as breathing. Julia Kerninon's A Respectable Occupation joins the shelf of these biblioautobiographies; books on how writers crave books, how books beget books, how tricky it is to move from the position of the reader to that of the writer, and stand there feeling you've earned the right to call yourself, finally, a writer." —Lauren Elkin

Rave by Rainald Goetz $38

Rave is the fruit of Goetz's intense collaboration with major figures from the early electronic music scene, among them Sven Vath and DJ Westbam. An unapologetic embrace of the nightlife under the motto `Meet girls. Take drugs. Listen to music', this fragmentary novel attempts to capture the feel of debauchery from within while at the same time critiquing the media structures that contribute to the 'epochality' of pop culture phenomena. Throughout the four decades of his career, Goetz has sought to dissolve the critical distance between writer and object which, in the quest for distance, actually distorts its object; in Rave he dives fully into dissolution, celebrating what is neither counter-culture nor `mass culture' in Adorno's disparaging sense, but a new way of experiencing mental processes and intimacy.

"Rainald Goetz is the most important trendsetter in German literature." —Suddeutsche Zeitung

>>Read Thomas's review of Insane.

>>Goetz cuts his head open for the 1983 Ingeborg Bachmann Prize (a sort of Germany's Got Talent).

A Silent Fury: The El Bordo Mine Fire by Yuri Herrera $35

On March 10, 1920, in Pachuca, Mexico, the Compañía de Santa Gertrudisth—thelargest employer in the region, and a subsidiary of the United States Smelting, Refining and Mining Company—may have committed murder. The alert was first raised at six in the morning: a fire was tearing through the El Bordo mine. After a brief evacuation, the mouths of the shafts were sealed. Company representatives hastened to assert that "no more than ten" men remained inside the mineshafts, and that all ten were most certainly dead. Yet when the mine was opened six days later, the death toll was not ten, but eighty-seven. And there were seven survivors. A century later, acclaimed novelist Yuri Herrera has reconstructed a workers' tragedy at once globally resonant and deeply personal: Pachuca is his hometown. His work is an act of restitution for the victims and their families, bringing his full force of evocation to bear on the injustices that suffocated this horrific event into silence. Harrera's book has the penetrative effect of a novel.

"Searing, painful, poetic, simple, extraordinary." —Philippe Sands

>>Yuri Herrera talks with Fernanda Melchor.

>>Other books by Yuri Herrera.

Handmade in Japan: The pursuit of perfection in traditional crafts by Irwin Wong $135

A beautifully presented record of the care, skill and aesthetic sensibilities of practitioners of traditional Japanese crafts.

Mā Wai e Hautū? by Leo Timmers (translated by Karena Kelly) $19

A new play on the fable of the tortoise and the hare. This is a picture book for drivers of all ages, now available in te reo Māori.

Sisters by Daisy Johnson $37

Something unspeakable has happened to sisters July and September. Desperate for a fresh start, their mother Sheela moves them across the country to an old family house that has a troubled life of its own. Noises come from behind the walls. Lights flicker of their own accord. Sleep feels impossible, dreams are endless. In their new, unsettling surroundings, July finds that the fierce bond she's always had with September is beginning to change in ways she cannot understand. From the author of the Booker-shortlisted Everything Under.

"A short sharp explosion of a gothic thriller whose tension ratchets up and up to an ending of extraordinary lyricism and virtuosity." —Observer.

>>"It's not an easy time to be looking at yourself or other people."

Stalin's Wine Cellar by John Baker and Nick Place $40

Stolen from the Csar, hidden from the Nazis, and found by a Sydney wine merchant.

>>Is this the secret cellar?

Book of Wonders: How Euclid's Elements built the world by Benjamin Wardhaugh $40

Wardhaugh traces how an ancient Greek text on mathematics – often hailed as the world's first textbook – shaped two thousand years of art, philosophy and literature, as well as science and maths. Writing in 300 BC, Euclid could not have known his logic would go unsurpassed until the nineteenth century, or that his writings were laying down the very foundations of human knowledge.

>>Byrne's edition of Euclid.

The Smallest Lights in the Universe by Sara Seager $37

After spending her career peering into the stars in search of Earth-like planets, Seager found her connections with an Earth-like planet much closer to home following the death of her husband and the realisation that her Asperger's affects how she relates to every part of the universe.

One, Two, Three, Four: The Beatles in time by Craig Brown $37

Deals with the minutiae of the Beatles metamorphoses in a lively way, but looks at their interactions with, and effects upon, the wider world.

>>All Together Now.

From a Dark Cave to New Zealand by Mustafa Darbandi $30

The remarkable story of a refugee's flight from Iraq to Turkey to Iran to Pakistan to Afghanistan and finally to New Zealand, his life always in danger, first because he belonged to a banned Kurdish political organisation, and then because of security forces, mercenaries, police, helicopters, landmines, wild wolves and even UNHCR indifference.

Do You Read Me? Bookshops around the world by Marianne Julia Strauss $120

You want this book.